vernadsky

Popular religiosity, Sophiology with its Fedorovian, cosmist charge, and the alchemical unconscious of Marxist theory are the three distinct but in some ways related “holy families” of Russian immanentism. On the level of ideas, the various members of these families are easily coupled and hybridized, despite their heterogeneity. In consequence, we witness the emergence of a kind of ideological field of integral immanentism in the first decade of the twentieth century.

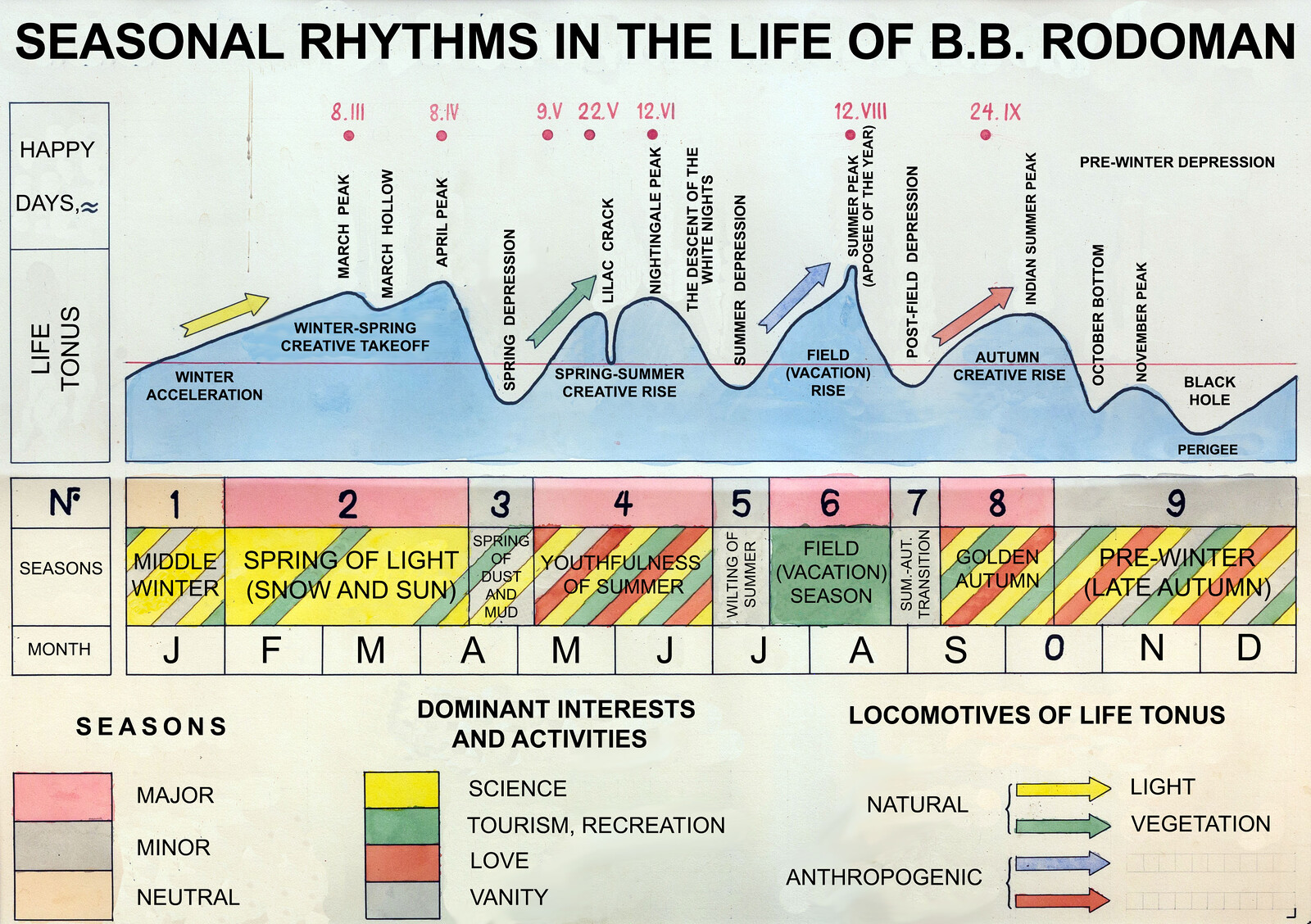

In Boris Rodoman’s map-like diagrams we are confronted not only with the features of the objects being mapped (a landscape, the author’s experience, or his interests), but also with the mapping procedure itself as a fundamentally important and basic feature of the human mind. The common link between a cartoid that depicts a model of a landscape and a cartoid that schematizes the interests of its author reveals the very procedure of mapping as primarily a cognitive process. Moreover, by charting and mapping himself and his own interests, the researcher makes visible the processes of constructing the subject. In other words, through his geo-cartoids, Rodoman reveals the action of forces and flows of power that construct the subject in many respects as a random assemblage. Rodoman’s geo-cartoids contain an implicit critique of the Russian landscape and the powers that constitute it (hyper-centralization, the influence of administrative divisions, and so on). His para-geographical cartoids do the same kind of work concerning the construction of subjectivity in modern society.

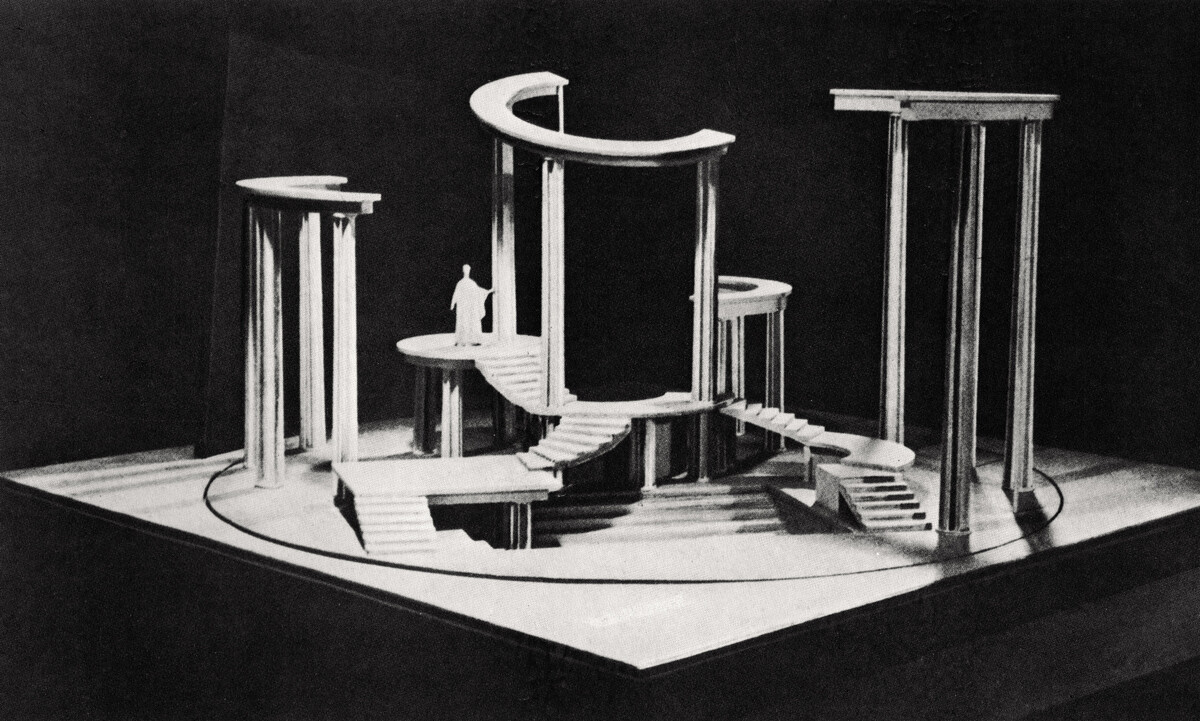

Cosmist thinkers founded the “organization of world-transformation”—an organization that was meant to encompass all the types of humanity’s creative activity, all spheres of its theoretical and practical application—on the creative principle found in art. Art opens before humanity an opportunity to move away from the present instrumental, technical progress, which acts upon nature only from outside, by use of mechanisms and machines, to a new, mature type of progress that would be organic, that would transform and spiritualize the world through a living, non-mediated touch.

As absurd as it sounds, cosmism was part of a cigarette company’s advertisement campaign, and Yuri Leiderman’s work flew into space together with Andorra’s painting, which was hand-applied directly to the surface of the missile, as well as a text by the Kyrgyz writer Chinghiz Aitmatov. Leiderman’s photographs depicting the urn graves of the Donskoy Cemetery and Crematorium in Moscow were printed on a plastic film applied to the upper part of the proton rocket. After exiting the earth’s exosphere, the rocket burned up. This incineration aimed to represent the established connection between the ashes of the dead and the cosmos, as a prefiguration to their forthcoming resurrection. Instead of approaching cosmism only in a metaphorical way, Leiderman realized a concrete cosmist action motivated by a love for humanity.

“Cosmology of the Spirit” proclaims the necessity of communism from the point of view of the universe’s immanent logic of becoming. In Ilyenkov’s text, communism turns out to be a much more serious historical and cosmic event, not limited to the scale of the planet. If the world still exists, this is because it was shaped by a previous cycle of the ontological machine whose necessary cog is fully actualized communist reason.