Luis Camnitzer Read Bio Collapse

Luis Camnitzer is an Uruguayan artist living in New York.

When the US Constitution was drafted, the definition of the word “art” didn’t exactly coincide with today’s Art Basel version. On the positive side, Clause 8 recognized intellectual work as a form of actual labor. The founding fathers would have supported my demand for a dollar. On the negative side, Clause 8 set down guidelines that, by promoting applied knowledge in a world defined by the hope for certainty, have today culminated in the push for STEM curricula.

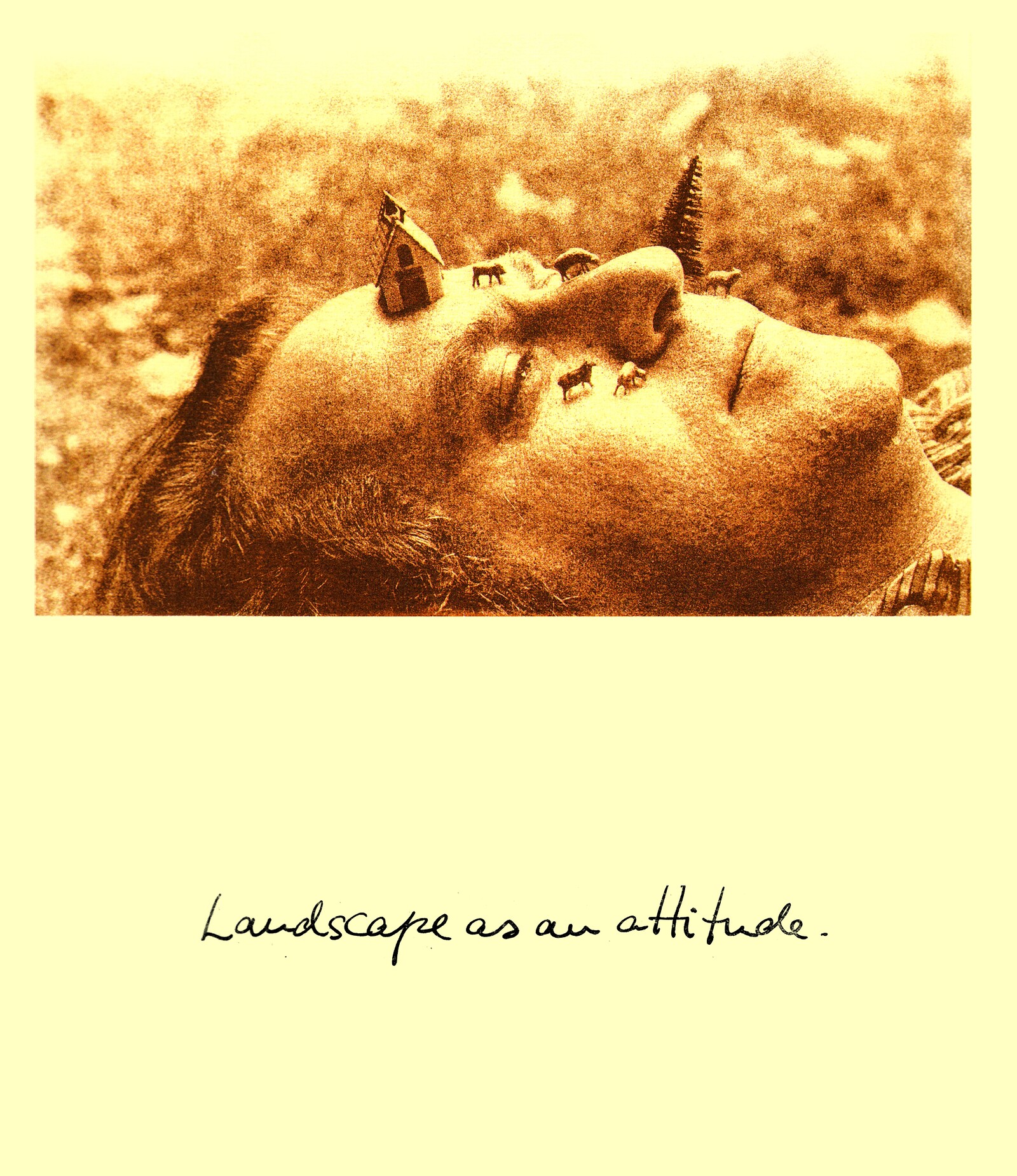

Without appealing to dogmas or causing any anxiety, art addresses facets of the unknown that hide other unknowns. Contrary to what science often assumes, mystery in art does not cater to obscurantism but instead opens minds. Mystery is one state of knowledge that the artist may actively use to contextualize and enrich rationality. Unlike other forms of knowledge, it maintains endless imaginative flexibility by disorienting and reorienting us.

Today I have become a member of that same generation I despised when I was a student. This was a slow and insidious process that I only perceived gradually and marginally. I started thinking about retirement when a student who was a fan of hip-hop asked me what music I liked. I answered that I favored classical music. After a long silence he looked at me and said, “Oh, you mean The Beatles?”

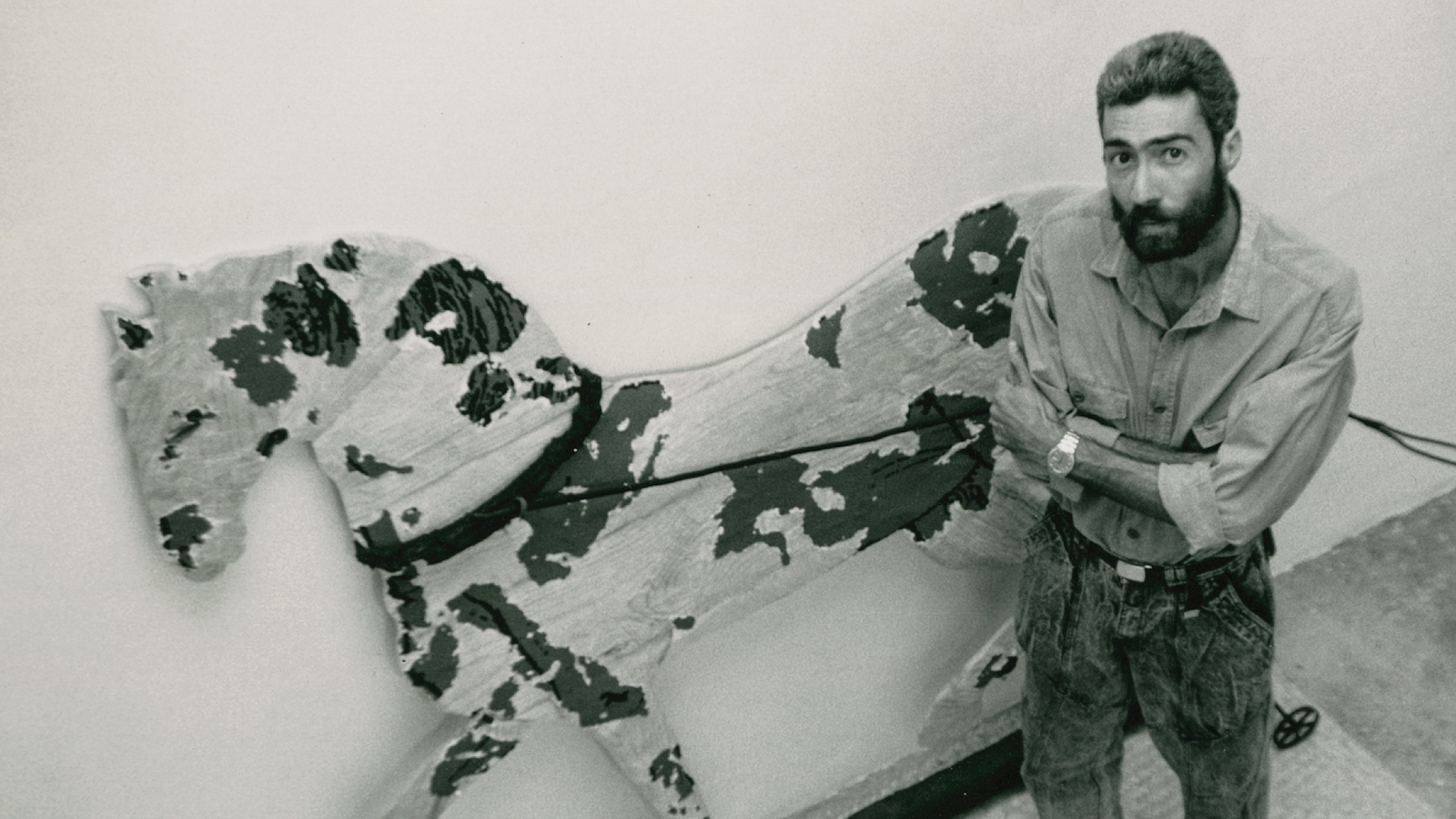

Antonio died on March 29, 2021, apparently from heart failure, the primary organ he used to generate his works. He died prematurely at the age of seventy. He has been one of the few irreplaceable characters in the art of the South American continent, and luckily, his work will remain and compensate for his leaving us.

More than six decades of writing by influential artist and teacher Luis Camnitzer that interrogate the power structures inherent to the practice of art at the same time as they explore its liberating potential.

I don’t believe that there is any other aesthetic premise than freedom, as much personal as collective. As this is also an ethical premise, I don’t believe that one can detach aesthetic premises from pedagogical methodologies. In reference to art, leaving aside any precise definition, I understand that it should be a universal form of expression, since every action should be aesthetic and everything should be creative. The opposite is neutral and stagnant. I understand that there is no “anti-art” but, if anything, there is an “other-art” with the same rights and validity.

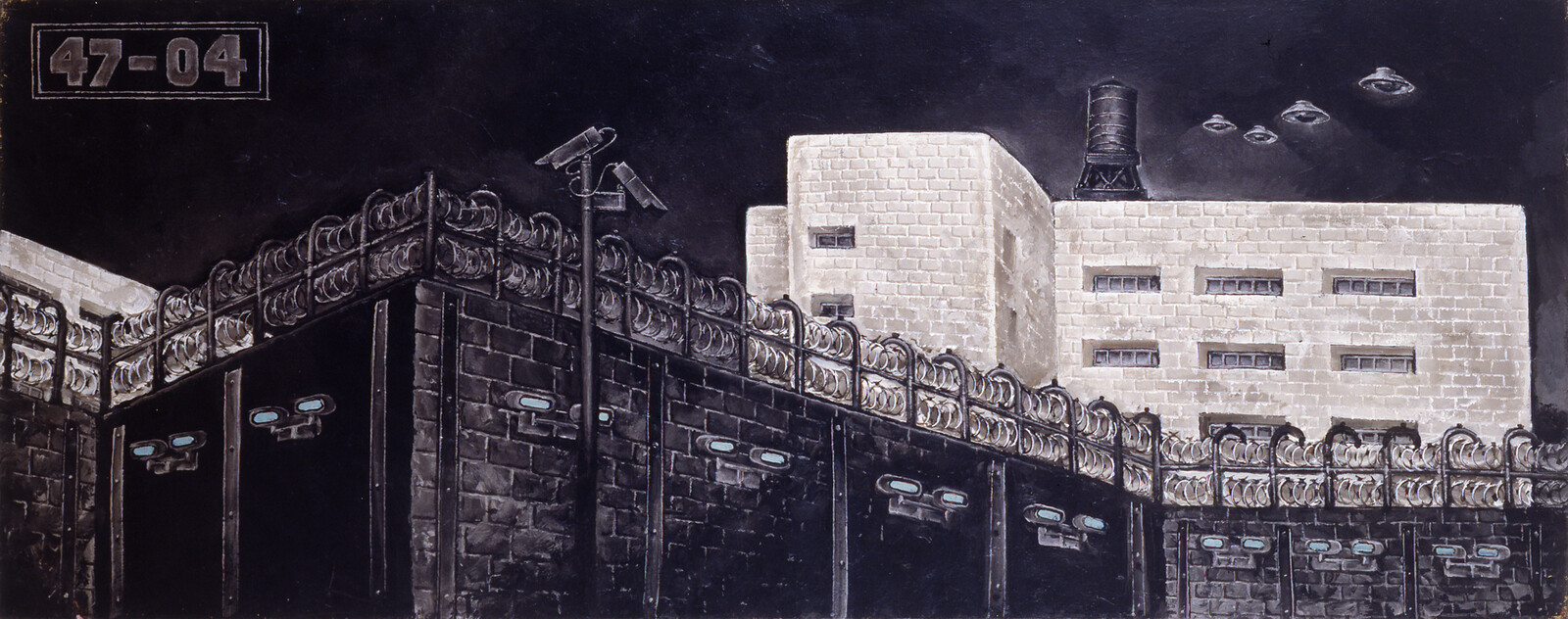

I like to use Aladdin’s lamp as a simile for what happens in the art world. Artists make their work as they would make lamps: in the hope that the genie is inside. Sometimes they even believe that they can control the presence of the genie. Museums then display the art-equivalents of the lamp, betting, not just hoping, that the genie is in there and will stay there for the foreseeable future. The genie is intangible while the lamps are not, so attention tends to focus on the technical execution of the lamp, hence the emphasis on crafts and finish, or, after Duchamp, on how well they were intellectually framed as objects capable of containing the genie. The genie is in the lamp because museums say so, and the canon is the measuring stick with which they validate their statement.