James T. Hong Read Bio Collapse

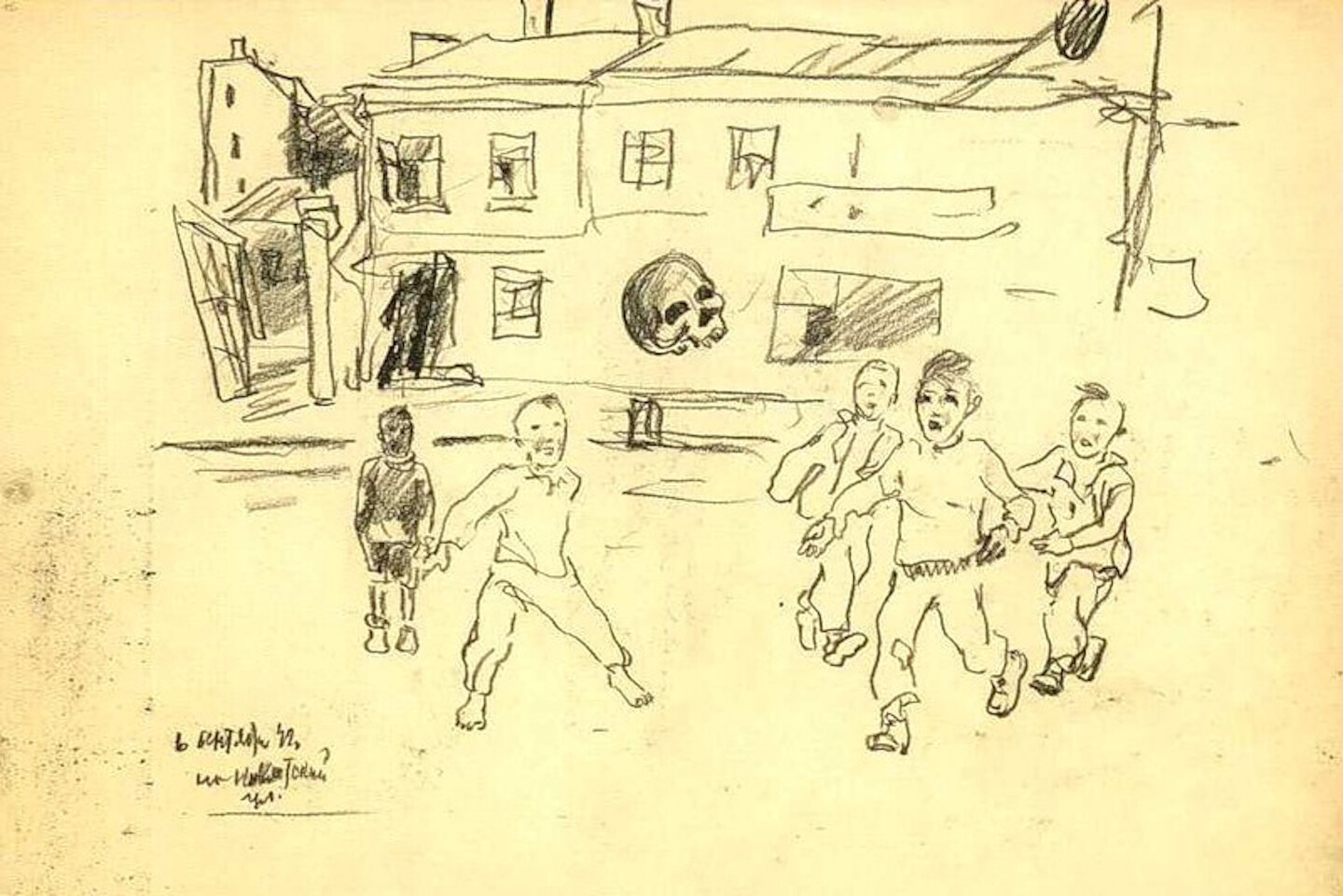

Taiwanese-American filmmaker and artist James T. Hong (b. 1970) creates thought-provoking works that prompt conversation on controversial socio-political and historical issues. His films have premiered at international film festivals, including San Francisco International Film Festival (2007), IDFA (International Documentary Festival Amsterdam) (2012), Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale), and Busan International Film Festival (2019), where he won the prize for Best Documentary (Mecenat Award) for Opening Closing Forgetting (2018), a film that follows Chinese survivors of Japanese biological warfare. He has screened films, and presented multimedia installations and performances in biennials and museums around the world, including Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) (2013), Mediacity Seoul Biennial (2014), Kiev Biennial (2016), Para Site, Hong Kong (2015), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (2017), and Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore (2018). He has participated in several editions of the Taipei Biennial, most recently “You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet” (2020), curated by Bruno Latour and Martin Guinard. His 2021 solo show Animal at the UK’s Ikon Gallery just recently closed. Hong’s work is represented by Empty Gallery, Hong Kong. He lives in Taipei.

In more than 60 texts, first published on-site at 56th Venice Biennale, artists and writers trace the negative collective that is the subject of contemporary life.

For fake news to exist, there must be a “real news.” A lot of news, or what counts as news in Taiwan, for instance, is a weak kind of fake news, because Taiwanese news stories are frequently too trivial even to be considered news (e.g., a new restaurant forgot to include free napkins). In these trivial cases, truth or falsity does not even matter. But the “fake” in fake news has a metaphysical component. What type of metaphysics is a criterion for distinguishing fake from real news? For most people, only another story or collection of stories can prove that a particular story is factually wrong (unless one actually witnessed the news-making event). There is no way for a regular reader to go above and beyond any particular news story to adjudicate its truth value from God’s point of view, so she can only arbitrate between competing stories filtered through her own prejudices and biases. Furthermore, something is usually off about any news story—a detail, a nuance, the choice of words, implicit and explicit prejudices.