Benjamin’s concept of experience, Erfahrung, remains speculative in the best non-positivist sense of the word. Its speculative ground, however, exceeds the speculations of theory. But what is left for the materialist intellectual who is to theorize the political, economic, social, and aesthetic conditions of poverty, deprivation, and precarity in the age of “very-late” capitalism? Eventually, Benjamin’s materialist argument comes down to a simple insight: the combination of poor experience and rich thought is poor in social consequences. Instead of gradually enriching thought through inclusive multidirectionality, radical thought must insert reductive shortcuts, one-sided interruptions.

The discourse of Marxism, on the contrary, produces not trust but distrust. Marxism is basically a critique of ideology. Marxism looks not for a “reality” to which a particular discourse allegedly refers but to the interests of the speakers who produce this discourse—primarily class interests. Here the main question is not what is said but why it is said.

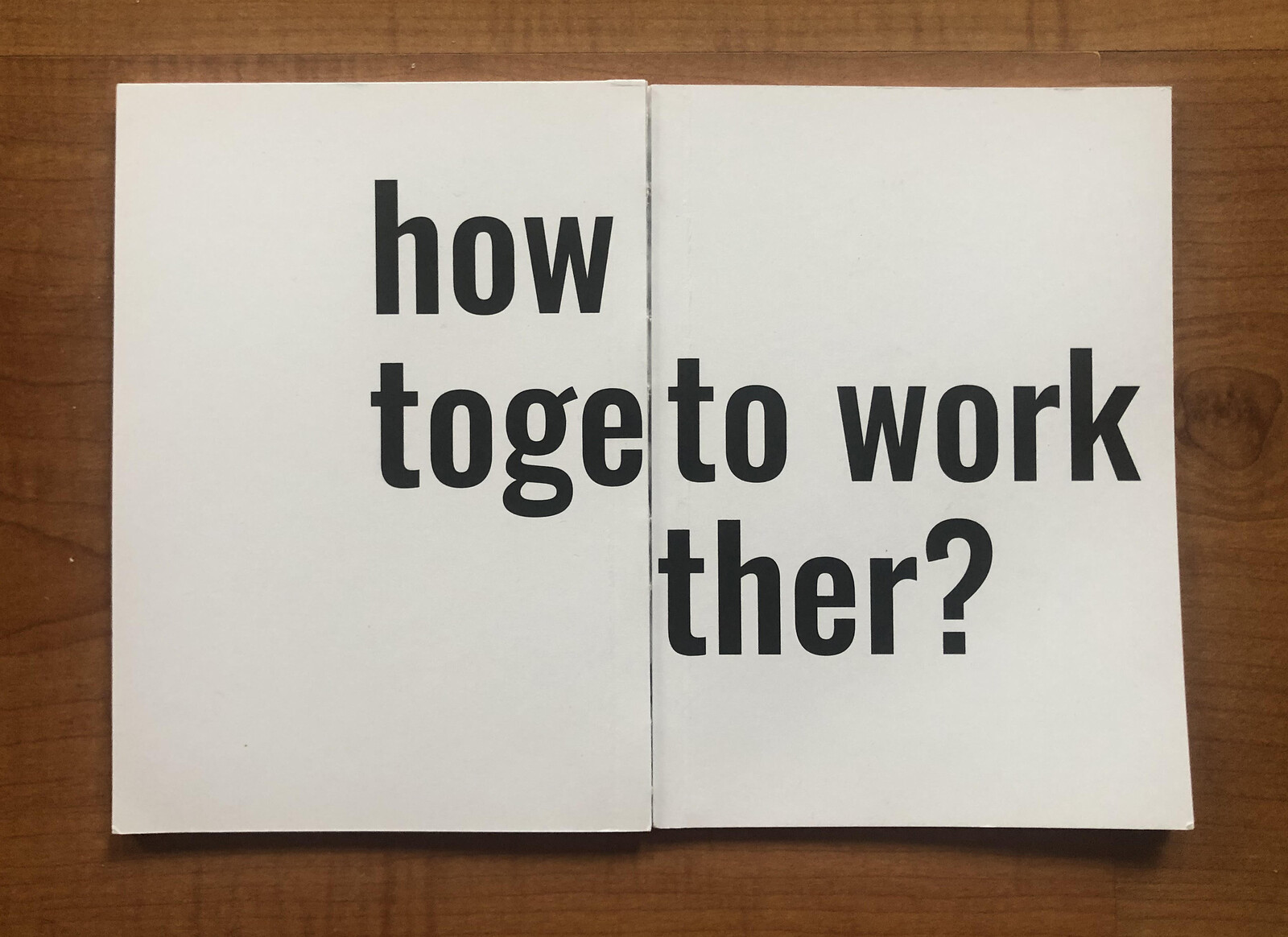

Contemporary art is not the production of the institution, but is rather the institution itself. The relationship between the structure of production and the product is very entangled. They both function on the same economic basis: proposal writing. It is a framework of thinking and an act of language that is always happening in the future tense: “The project aims to …,” “The work will …,” etc. Writing the proposal becomes part of the artwork itself. The person who knows how to explain the proposed piece, mainly in English, will be more likely to get grants. This process relies on the artist’s embeddedness in spaces that hold cultural capital, and not only on the artist’s or the work’s merit. The claim of equality in open calls for funded projects is contested.

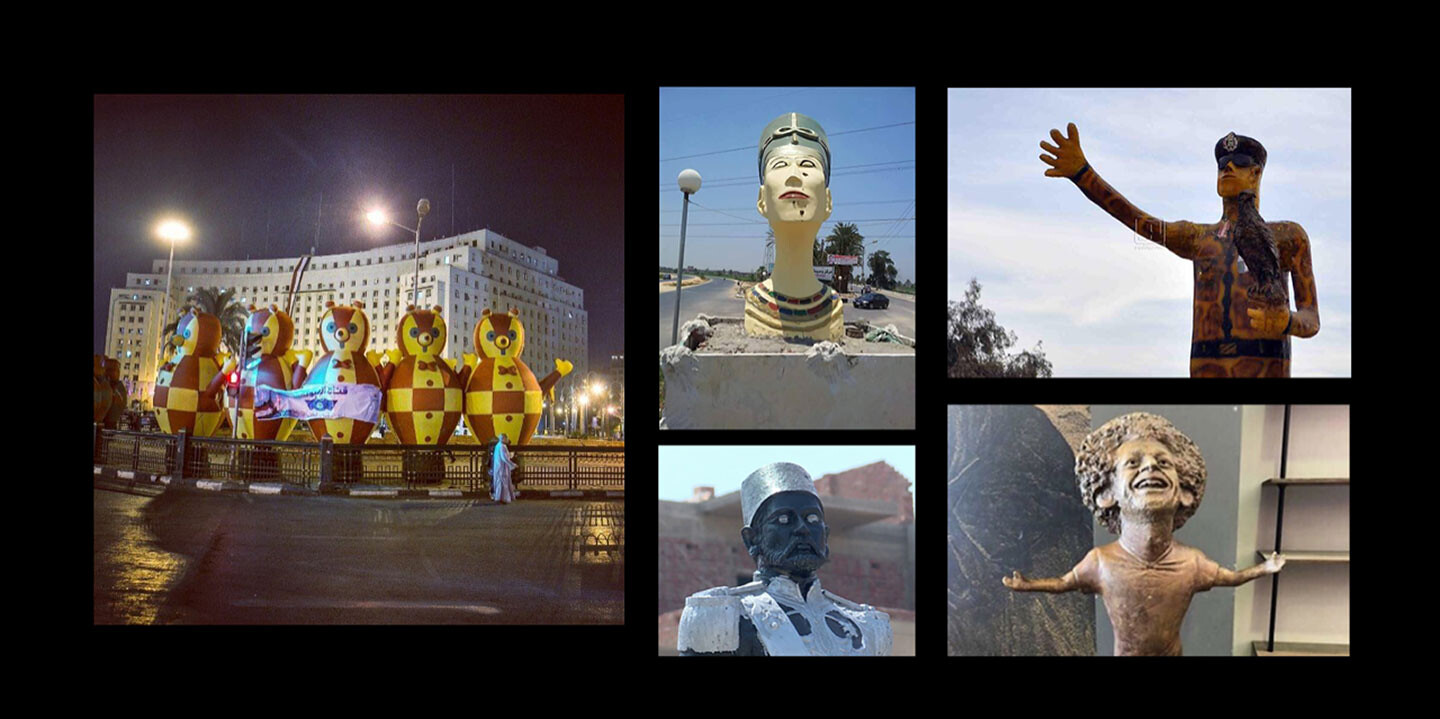

The mocking of official structures and roles is surely not new, but the subject position from which it emerges is. For many years, it has been the traditional role of satirists, artists, dissidents, and cultural and social commentators to undertake such comic caricatures, with the aim of shaking belief in the stability of historically significant figures, narratives, and gestures, but rarely, in recent memory, have such caricatures been performed from the subject position of the very institutions they were meant to deconstruct. For now the monument and its parody, the president and the comedian making fun of what a president is, are one and the same. So what happens when the parody is not performed from the margins attacking the center, but is identical with the original, or more precisely is the original?

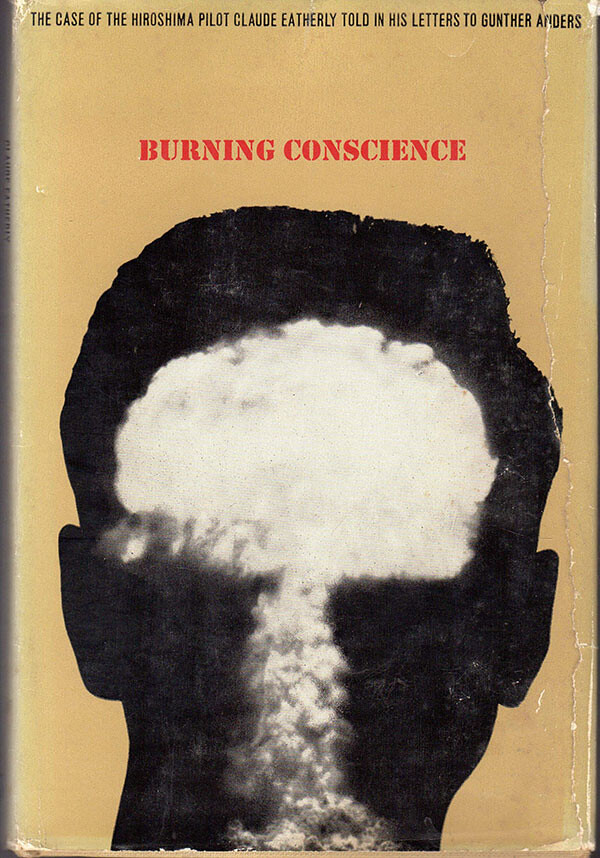

It is now accepted that we are moving towards a new phase of world war: war by algorithm; and specifically the development of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS)—systems that are, essentially, outside human control. In November 2019, US Defense Department Joint AI Center director Lieutenant General Jack Shanahan (in conversation with Google CEO Eric Schmidt) spoke frankly about a future of algorithmic warfare: “We are going to be shocked by the speed, the chaos, the bloodiness, and the friction of a future fight in which it will be playing out, maybe in microseconds at times. How do we envision that fight happening? It has to be algorithm against algorithm.” If the very idea of humanity rests, at least in part, on an ability to imagine the other’s suffering, then what is being signposted here is a movement towards humanity’s final negation.

One of the things that “absurdism” did was to undermine the expediency of all language that was meant to be believed simply because it was uttered. This is still unwelcome politically, whether it is the “realism” of official Soviet aesthetics, the “promise” underlying a financial product, or the “organic truth” of Nazi ideologists like Alfred Rosenberg, or indeed whether it is the memes, metaphors, and allegories of the far and populist right that freely borrow from their ideological predecessors: all of these doctrines and “interfacial regimes” rely on believing their own performative phraseology. This is true whether such regimes are messy or systematic, whether centrally imposed or adopted as part of news cycles, troll and bot attacks, hashtags, likes, and retweets. Klemperer writes that the Third Reich, with its permanent accumulation of “historic” events and “momentous” ceremonies, was “mortally ill from a lack of the everyday.”