Twenty-five million people recently went hungry in China’s most economically developed city. No one could have imagined this happening in Shanghai, where per capita disposable income is the highest in the entire country. The reason wasn’t insufficient food supply.

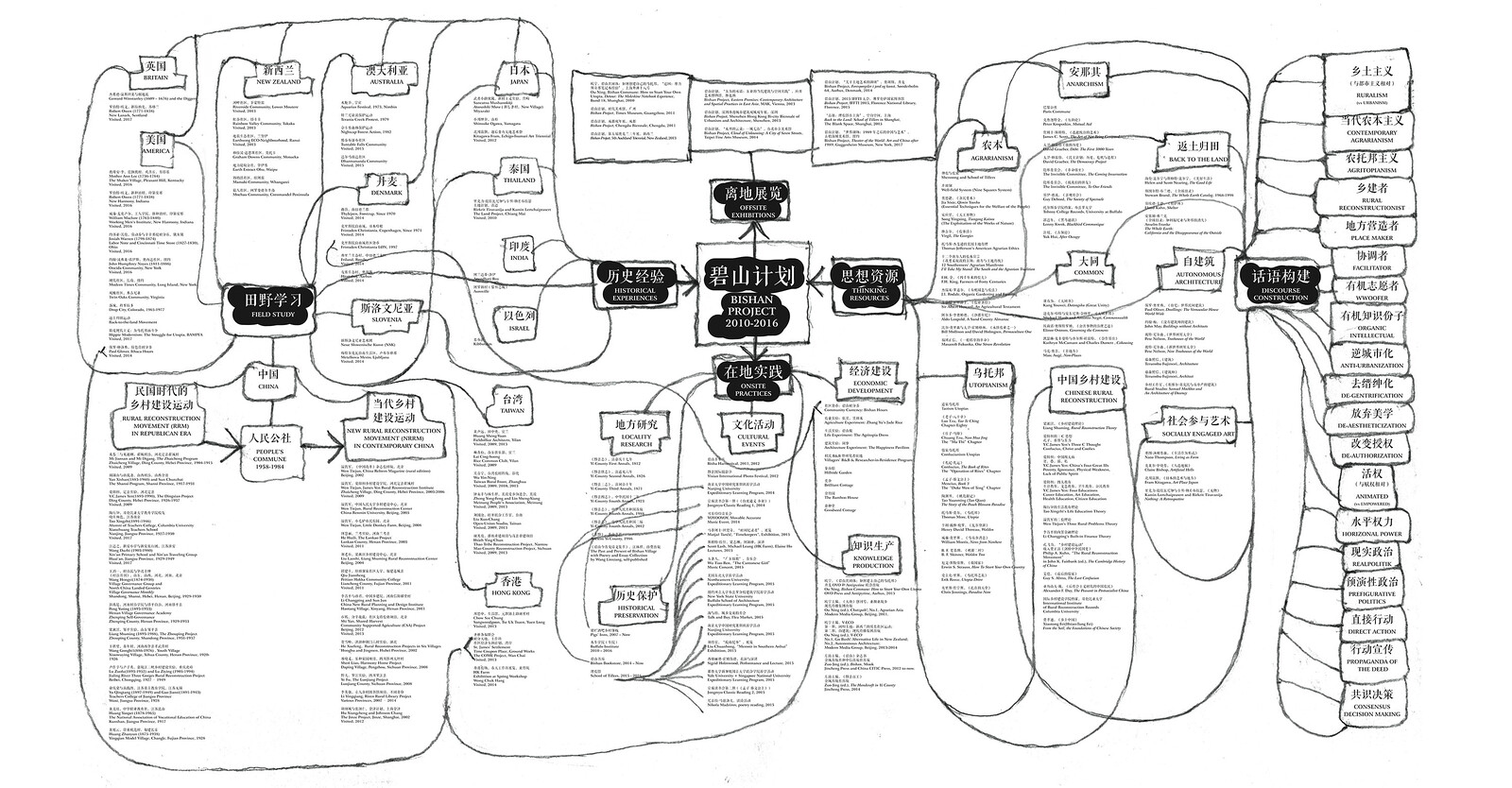

Farmers are not “human waste” eliminated by the modernization process, as many people think. Their “cunning” wisdom is often unexpected. Their “brain mine” (to use James Yen’s term) is rich, but ignored. The problem of contemporary Chinese farmers is that they live at the bottom of an “authority-driven” society where state power permeates in a totalizing way. These farmers can neither return to the “autonomy of the landed gentry” of the era of monarchy, in which “imperial power extended down only to the county level,” nor can they speak through the electoral system like American farmers. The space to realize their potential is very limited. As an outsider with neither power nor capital, all I can do in the countryside is use my own cultural resources to improve farmers and villagers’ visibility in society, broaden their contact with the outside world, and build platforms within my ability to let them give full play to their intelligence. Under limited, realistic conditions, so-called “empowerment” and “moralization” are all extravagant to me, and they are also part of an elite rhetoric that I oppose. I prefer the words “mutual aid,” “mutual learning,” and “communal life.”