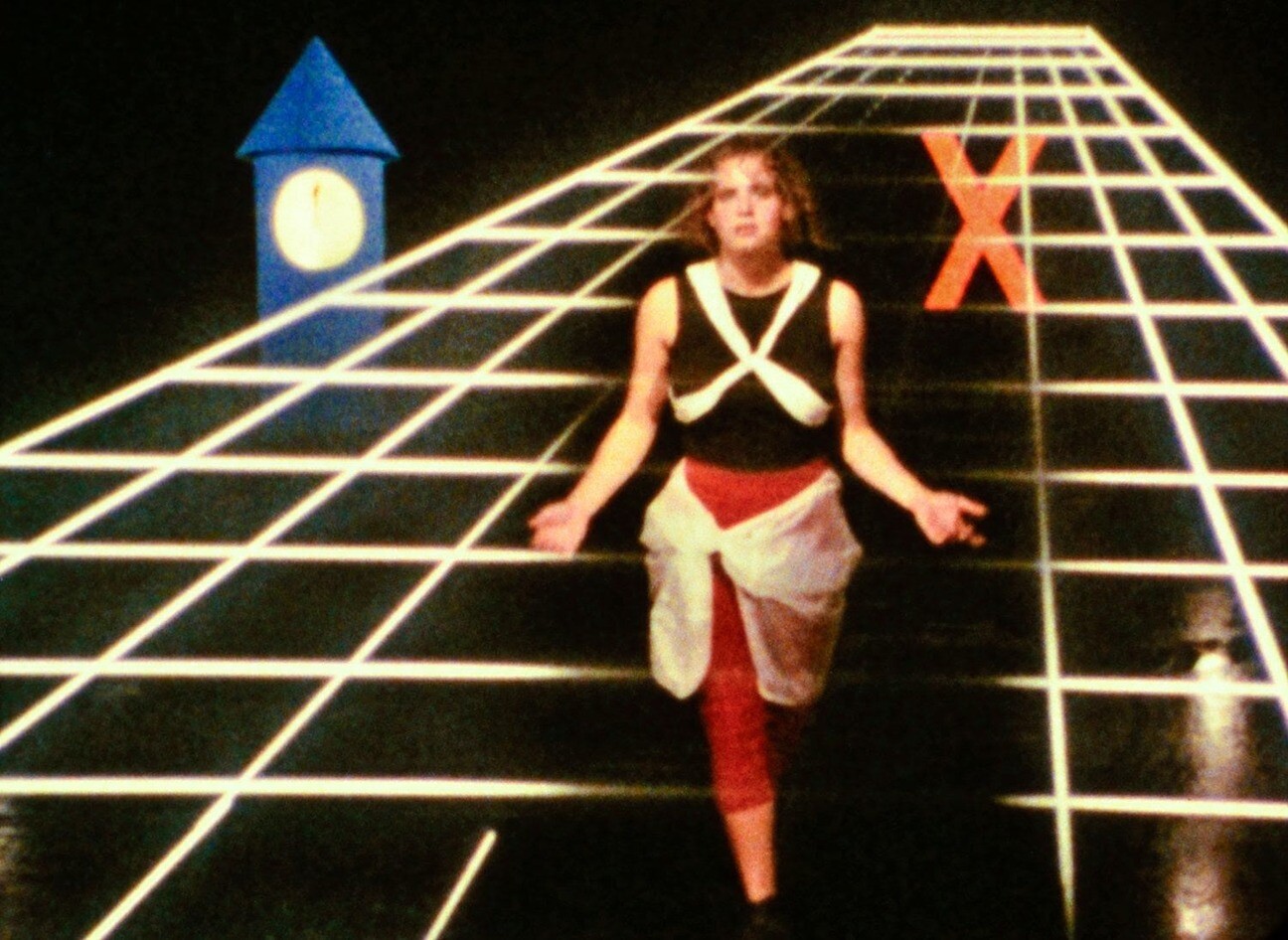

Ericka Beckman, Cinderella (still), 1986.

On February 13, 2025, in conjunction with Ericka Beckman’s solo exhibition on view at the Drawing Center, e-flux Screening Room presented Power Games: Winning Isn’t Possible, a retrospective screening of films by Beckman. The screening was followed by a conversation between the artist, Lukas Brasiskis, and the audience. The transcript of this conversation was edited for the present publication.

Question: While often associated with the Pictures Generation, your cinematic approach sets you apart from artists like Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo, who primarily worked with photography and appropriation of images from popular media. What led you to film as your primary medium? How did the transition from painting to film happen?

Beckman: When I was a graduate student at CalArts in the mid-1970s, Miriam Shapiro came into my studio for my first critique. I showed her paintings on paper. She said to me, “If you want to be successful as a woman artist, you cannot make beautiful things.” Luckily, I had begun making Super 8 films. At the time, I was deeply engaged in performance, dance, and experimental music, and I wanted to transition from working in two-dimensional media to something more dynamic. The genesis of my work in film stems from two things: the camera itself and research. I used a Fuji Super 8 camera, which allowed for full rewind, enabling me to experiment with layering and reworking footage. Unlike digital media, where you can immediately see the results, film required improvisation—you had to structure your shots and then allow for unpredictability. That interplay between structure and chance became a defining aspect of my process.

My early work combined live action with animation, layering performative improvisation with additional visual elements. This approach led me naturally to an interest in gaming. By 1979, I was fully immersed in exploring games as both a subject and a structural principle in my films.

New York at the time provided a vibrant and collaborative environment for filmmaking, even without a budget. You could create work within a single studio, involving musicians and performers who shared similar interests. Music was a core element that bound the community together. But beyond the immediate creative scene, my engagement with gaming also came from research. Before making You the Better (1983), I spent a year studying game theory and philosophy, drawing extensively, and researching in libraries. I wanted to integrate these ideas into a cinematic framework that wasn’t purely academic but instead felt performative, musical, and immersive.

Question: Your films often explore systems that govern behavior. Reach Capacity (2020), for instance, offers a direct critique of economic structures. You’ve said that the impulse behind each project often comes from your emotional response to certain problems. Can you expand on that?

Beckman: Making a film takes time and effort, and for me, the impulse behind each project always comes from two things. First, I’m trying to figure something out—the film itself becomes a way to work through a problem. I rarely have a fixed ending in mind. For instance, with Reach Capacity, which I made during the pandemic, my original plans had to shift drastically when production became impossible. So filmmaking, for me, is often a puzzle—sometimes an intellectual one—where I’m working out how to articulate a complex idea, often something philosophical. I don’t necessarily aim to make a film entertaining, but I do think about how to make ideas resonate. I want the words and images to linger with the audience, to stay with them beyond the screening. Music plays a major role in that—it drives the structure of my films. But yes, each of my films does begin with anger, with something that’s really bothering me, something I need to work through.

That anger serves as the initial impulse, but once I begin working, it quickly transforms into something playful—there’s a joy in the process of making the film, in collaborating with performers and musicians. So for me, there’s always this duality: an urgent need to express something at the core of my energy that then gets translated through structured systems of play.

Take You the Better, for example. Reagan was changing the economic policy in America by deregulating the banks and making them for-profit corporations. Suddenly I was aware that ordinary people, their earnings and savings, were considered tokens in a game of corporate competition, and that made me angry. I wanted You the Better to explore the idea of chance—not chance as a term to describe chaos, which is how it’s often defined, but as something with its own function and energy that is generative rather than creating disorder. A chaos that can create change.

So I thought, how do I represent chance in this film? I decided to do it through gameplay. I incorporated it not only as the games I chose for this film, but also as a mechanism in the production itself. The performers played a series of ball games, starting with simple games of chance and building up to strategic team sports. I used superimposition after the performances to add the animated game elements—they had no idea what they were hitting or striking at any moment. I added an off-screen better to the process, and a one-armed bandit, as in casino games, to add more chance elements into the film. That spontaneity was essential to the film’s structure, and from there, the whole project took on a life of its own.

Question: While references to the real world are present, your films ultimately create self-contained universes that remind me of Fernand Léger’s films. In these filmic worlds all elements within the frame, including human actors and material objects, seem to hold equal significance. Could you talk about the production process and how you develop these worlds?

Beckman: Generally, games are enclosed systems—they are a provisional reality. I felt films and games were very similar. I could describe several, but let’s focus on Reach Capacity because three major elements came together in its development. First, I discovered the precursor to Monopoly, a board game designed by Elizabeth Magie in 1902s called The Landlord’s Game. Her original version was created as a socialist game to demonstrate the dangers of monopolies. The game was played with two sets of rules. First, it was played as Monopoly as we know it. Once a monopolist was created, the board was flipped over and the same game continued with new rules that allowed players to redistribute the monopolist’s wealth.

The game was widely played within Quaker communities, particularly in Pennsylvania, until a Wharton School of Economics student took the concept to Parker Brothers during the Great Depression. They bought out her patent for just $500, erasing her from its history. Learning about this deeply frustrated me.

When I discovered The Landlord’s Game, I was caring for my mother in St. Louis and witnessing a historically Black neighborhood where families had owned homes for generations being bought out and bulldozed to make way for the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), a military surveillance and drone operation hub. Families were forced to sell without receiving enough financial support to relocate, often pushing them into mortgage debt. Meanwhile, in New York, I was losing my rent-controlled artist studio in Lower Manhattan, watching high-rises replace affordable spaces. These simultaneous injustices became the driving force behind Reach Capacity.

Each of my films takes shape through a layered creative process. I distill my ideas into lyrics—short, rhythmic phrases—and then shape the visuals around them. Every film has a distinct tone, and the music and lyrics evolve alongside the visuals. For Reach Capacity, I wanted the tone to mimic the relentless, intrusive nature of late-night advertising. That repetitive, almost hypnotic style felt fitting for the themes I was addressing.

There’s also a practical element to my process—because my films are largely self-produced, without consistent grant funding (which dried up for me after 1994), production happens in stages. There are inevitable pauses and interruptions, but those constraints also shape the work in unexpected ways.

Question: There seems to be a strong resonance between your early and recent work, particularly between You the Better (1983) and Reach Capacity (2020). Despite the decades between them, both films share thematic, visual and sonic similarities. What led you to revisit the same ideas after such a long gap?

Beckman: That’s a great question. I returned to these ideas because I wanted to explore economic systems again. If you visit The Drawing Center, you’ll see Stalk (2023), which also deals with these themes. At this point, I’m committed to examining large-scale systems—big business, governance—and their impact on our lives.

You’re absolutely right in noticing the connection. I initially set out to create a companion piece for You the Better as a film installation with my light boxes, in the Belgium museum M Leuven. But this wasn’t just a strategic career decision—I felt a real need to revisit an economic game. That said, there’s a significant difference between my early and recent works. You the Better had a live environment with physical action, whereas Reach Capacity is more reflective and distanced. That shift has a lot to do with how my production process has changed over time.

Back then, the immediacy of live performance shaped the film’s energy. Today, production often happens remotely, particularly with elements like the soundtrack. I work with a composer in Los Angeles. With Reach Capacity, we started the music in my studio, with a few other singers, but had to complete it remotely due to COVID, which created a different dynamic. That’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot—how sound functions in a gallery or museum setting versus a theatrical screening. Over time, I’ve come to realize that audio is just as important as the visual component, and I’m constantly rethinking how best to present my work in different environments.

Question: You’ve worked with composer Brooke Halpin on and off for decades. How did you first meet, and how does your collaboration function?

Beckman: Brooke and I met at CalArts, which I chose as a graduate school to be close to John Bergamo and his group Repercussion Unit. I knew from the start that I wanted to make animated films with drumming. Brooke was a composer with his own distinct approach, but we had a very unique, productive form of collaboration based on improvisation. He and I sing together and develop rhythmic structures. I write all the lyrics and he helps refine them into a musical form, bringing his expertise in arrangement and harmony. We don’t work together constantly, but we’ve circled back at key moments. Our last film collaboration before Reach Capacity was Cinderella (1986). In between, I made several films independently. Our the most recent collaboration is Stalk.

Question: Your films often involve highly choreographed movements, as seen in You the Better. How do you direct your performers?

Beckman: I think of myself as both a director and a performer. In You the Better, Ashley Bickerton played a central role—he really carried the film. The structure of the film revolves around shifting vantage points, emphasizing different perspectives on the game’s mechanics. At a pivotal moment halfway through the film, the lead character reaches a point where he sees the larger picture, understanding how the game operates.

Spatial design plays a big role in my work. When I moved from Super 8 to 16 mm, I had a larger frame to fill. I wanted to explore expansive, dynamic spaces, but since I couldn’t physically access those locations, I built game-board environments instead. Circular structures became a central motif, allowing for movement and transformation. That circular motion remains a key element in my work, as it allows for shifts in perspective where you can pivot the action and change the agency of the performers.

Question: You worked on Switch Center (2002) overseas. How did its production process compare to your other projects?

Beckman: Switch Center was a highly improvised project. It was filmed in Budapest at a time of major political and economic transition, as Hungary was shifting away from Soviet influence and trying to establish a national cinema industry. The location—a vast, abandoned water purification plant—became the film’s primary subject. There was no pre-existing script; I built the film around the architectural space itself.

I worked with a small team from the Béla Balázs Studio, who performed in the film wearing overalls. One day, I arrived to find that a Pokémon commercial had just been shot in the same space, so I decided to incorporate that into the film. This kind of reactive filmmaking—responding to space, light, and the shifting circumstances of production—was central to the process.

Working in Budapest at that time was challenging, particularly as a female filmmaker. There was tension between leftist artists and those pushing for commercial industry success, creating a complicated and sometimes chaotic production environment. But that friction became part of the film’s texture. I was navigating shifting ideologies, different expectations of cinema, and the evolving relationship between art and commerce.

Question: I’m curious about your relationship with fairy tales. Your work often incorporates whimsical elements, both in the music and the visual language, with vibrant colors and a sense of play…

Beckman: I think what you’re asking is why I find fairy tales interesting to work with. In this case, it’s primarily about the audience. When I was making Cinderella, I did a lot of research into fairy tales and realized how deeply they critique cultural norms and societal pressures. There’s a scholar, Jack Zipes, at the University of Minnesota, whose Marxist analysis of fairy tales really influenced my thinking. His work helped me see these stories from a new perspective. I also took a Jungian workshop in Boston at one point that offered another way of understanding fairy tales—through a psychoanalytic lens. And then, of course, feminist writers and scholars in the 1970s and ’80s reworked fairy tales to challenge traditional gender roles and rethink the position of the male figure in these narratives.

The fairy tale can trigger a memory of childhood and then invite the audience to reconsider it with a critical perspective. I’m particularly interested in how childhood perception shifts over time and how we can return to those stories as adults with a new awareness. Stalk was based on Jack and The Beanstalk and it critiqued agribusiness. My next film incorporates the fairy tale Rapunzel as an entry point to compare machine learning and AI with biological learning. As a narrative form, fairy tales continue to fascinate me.

Question: You mentioned the difference between screening your films in theaters versus museums. Could you elaborate on how you navigate between the worlds of film and art? Do you find your work is received differently in these settings?

Beckman: It’s a simple answer. I was part of a 1980s art scene where artists, performers and musicians all hung out and made work together. I wanted my work to be part of that collective conversation. However, at that time films like mine were often relegated to museum auditoriums or experimental shorts programs at art house theaters and treated as secondary within the art world. I remember pushing to have drawings or posters displayed in museums alongside other artworks, just to make it clear that these films weren’t an afterthought but were integral to the artistic discourse.

Back then, curatorial decisions created strict boundaries. There were artists who only worked in video, filmmakers who either made experimental work or features, and documentary barely had a presence. Video artists were trying to transition into cable television, and filmmakers like myself were often leaving New York for Hollywood. It was a very different landscape, and the art world was largely unreceptive to moving image work, except for a small amount of video on pedestals. That changed significantly in the late ’90s.

Some of my best experiences screening my work from that period happened outside traditional institutions. One highlight was screening my films in an outdoor summer festival in Rome, in a tent alongside dancers. That setting—where my performance-driven films existed in direct conversation with live bodies on stage—felt like an ideal context. It created a striking dialogue between physical and virtual presence, which was a major concern in the early ’80s.

My career experienced a slump around 2000. In the ’90s, I had made Hiatus (1999), a large-scale film that took me into the worlds of VR, NASA Ames, and early internet culture. It screened at a festival but completely fell flat. It wasn’t until I reworked it as a double-screen installation that it found an audience again—this time in Europe in the mid-2000s. Around 2010–11, I experienced renewed recognition in Europe, which led to several exhibitions and touring programs. However, in those settings, sound often becomes a challenge. Museums and galleries aren’t built for audio, and reverb and resonance can completely alter the experience of a film. When I was working on my latest film, I was already thinking about how it would be installed, working with sound mixers to flatten the voice so that it would function within those echo-heavy environments. My approach to sound design has fundamentally shifted because of this.

Question: Given the rapid changes in the digital technology over the past decades—particularly the growing agency of operational images, as well as the increasing role of algorithmic and data-driven governance—how do you see your work adapting to these new conditions? Do you feel that your ongoing concerns with systems of control continue to evolve in response to the present moment?

Beckman: First of all, I’m starting a new project that deals with AI and machine learning, which feels like a natural progression because my work has always been about systems of control. But what’s especially interesting to me now is the way things are shifting toward biological forms. I’ve been researching this subject for over a year, and as I move into production, I find myself leaning into absurdity. Sometimes, the only way to address these issues is through exaggeration, and I’m embracing that approach.

For anyone interested in my new work, I’d encourage a visit to The Drawing Center. They have a 2024 piece of mine, Study for Rapunzel—The Game, where I have taken a new approach to animation, using only organic forms.