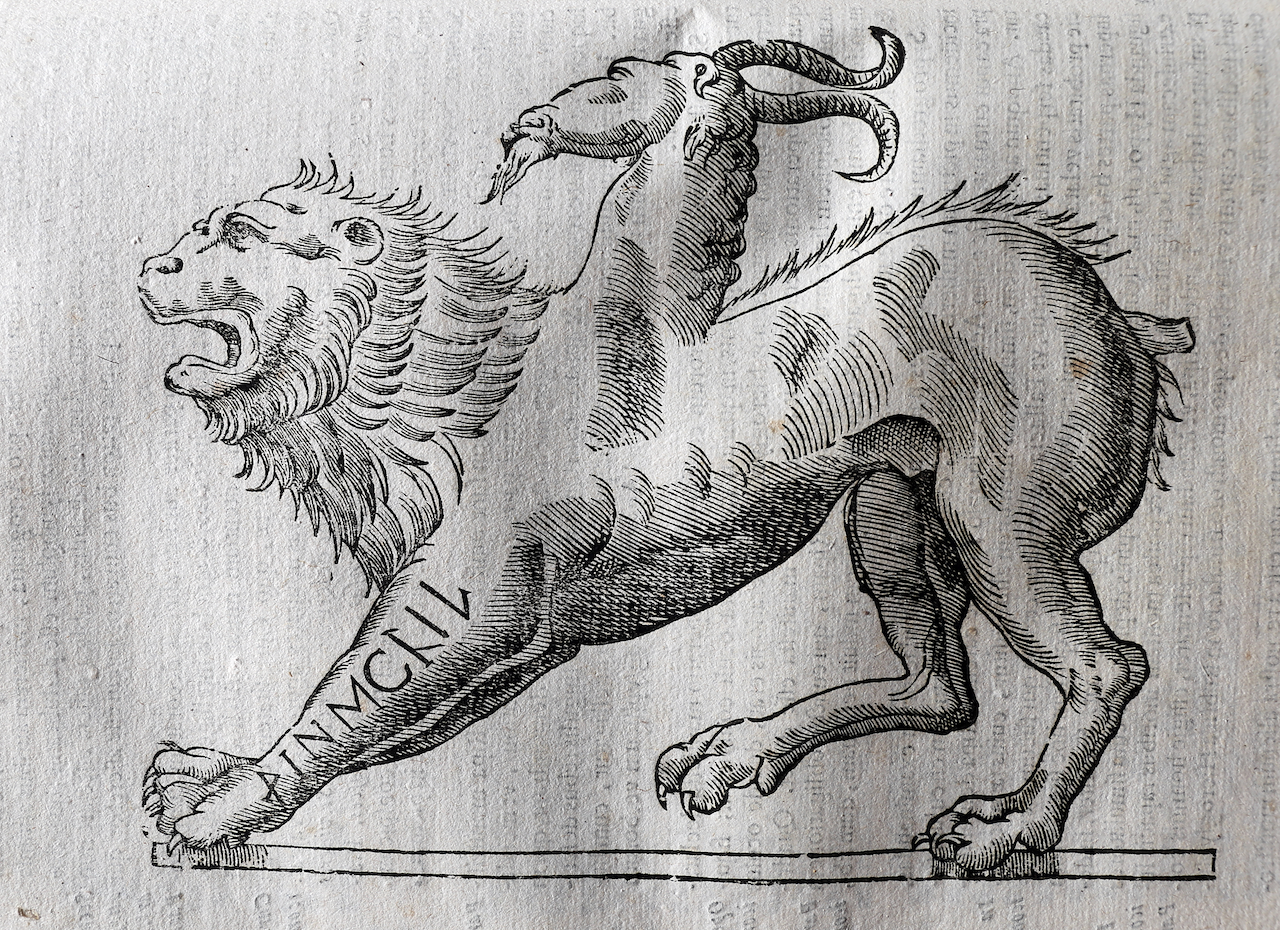

Ulisse Aldrovandi, Chimera, Monstrorum Historia (Bologna, 1642).

In 2022, I coedited the book Chimeras: Inventory of Synthetic Cognition, an AI glossary for which 150 international contributors were asked to provide a short article or an artwork.1 In Greek mythology, among the female deities embodying terrifying powers such as Eris, Hecate, Scylla, Medusa, the Erinyes, and Lamia, is Chimera, a demigoddess associated with fear. Chimeras are often depicted as composite creatures made up of different animal parts, such as a lion’s head that breathes fire, a tail that ends in a serpent’s head, or a goat’s body with dragon wings. A chimera is the prototypical synthetic being created by combining different parts, each maintaining some degree of autonomy. The term “chimera” is also used metaphorically to describe anything that is made up of diverse elements, or that is viewed as unconventional, fantastical, implausible, or strikingly imaginative. In genetics, “chimerism” refers to an organism that is a hybrid, composed of cells with different genotypes, occurring, for instance, when two distinct embryos merge, each contributing its own set of DNA to form a single entity.

The purpose of the Chimeras book was to shift the conversation about AI away from a purely technical narrative to a broader discussion about the technology’s impact and potential. It aimed to foster an environment where alternative viewpoints could thrive, challenging the notion that computer science holds all the answers regarding AI’s influence and possibilities. The figure of the chimera was particularly evocative in that context; chimeras have often been used to address cultural anxieties or to symbolize the integration (or lack thereof) of cultural and natural elements, reflecting how societies understand complex interdependencies. By employing various partial approaches and divergent disciplinary perspectives, the aim of Chimeras was to approach its subject indirectly—not to reduce it to its most essential, familiar, or structural components, but instead to complexify it. The interdependencies in that context were reflected in the interdisciplinary nature of the book, which embodied a diverse range of epistemic perspectives that are less represented in the general discourse about AI, including interspecies, crip, monstrous, distributed, and decolonial approaches, among others.

Chimeras was a statement, and an experiment in distributed cognition. Cognition is a networked activity, referring to the extensive capacity of living organisms to control and organize their internal structure while establishing their limits. Chimeric cognition, as the book imagined it, is accomplished through a sophisticated interaction of semi-independent parts—the chimera’s limbs and heads—that function beyond the usual frameworks of traditional advanced thought processes, without aiming for complete integration in a cohesive whole. The composite nature of chimeras and their capacity to navigate between different realms and symbolic domains, such as life and death, earth and sky, of the familiar and the monstrous, did not merely provide a convenient metaphor, but also a model for hybridity reflecting the distributed qualities and the amalgamation of various independent traits. Chimeras activated an expanded network of peers to think together through a complex topic. As one of the book’s contributors, the philosopher Anne-Françoise Schmid suggested that a model of collaborative interdisciplinary research is particularly fitting in the context of complex systems where multiple prismatic perspectives are needed to account for a research object composed of different models, incompatible scales, and heterogeneous objects. Chimeras didn’t attempt to foster a common language in order to bridge the gap between different regimes of knowledge production, but aimed instead to make of this gap the very same condition of working across disciplines. The book was shaped spontaneously from multiple short-form contributions and artworks—the independent but interrelated components and processes—in a relatively asynchronous and decentralized way, which in other media expressions would have made the process either too expensive, too slow, or extremely dependent on institutional support to initiate.

While the content and ideas presented in the book were significant, Chimeras was also a reflection on its context, understood both as an epistemic concept—it created a space for an imaginary, decentralized community through the coalescing of independent contributions in a larger project—and a commercial reality—the book’s radical absence from the market and the difficulty of placing it properly within existing publishing and distribution channels. Chimeras transcended its role as a mere vessel of knowledge, morphing into an operational model for working together. Herein lies the radical, transformative power of books—not in the words inscribed and the physical forms and materials of the book, and certainly not in the failing fragile markets they so strongly rely on, but in the relationships and context that books deftly orchestrate.

The same year as the publication of Chimeras, a Creative Europe consortium—consisting of the contemporary art center Aksioma in Ljubljana, the Institute of Network Cultures in Amsterdam, the publisher NERO in Rome, and Echo Chamber, a Brussels-based media research think tank—initiated a project on expanded publishing and alternative models for publishing. The Expanded Publishing research project aimed to reflect on the main challenges that are prominent in the multilingual European publishing world.2 Primarily, conventional publishing seemed to us increasingly limited in accommodating new forms of knowledge; collaborative works such as Aksioma’s (re)programming, time-based participatory practices, or long-term and durational creative projects cannot easily be contained in rigid traditional formats.3 Moreover, the timescale of conventional publishing is misaligned with the demands of projects that necessitate faster production pipelines—an urgency vividly examined in INC’s Here and Now? Explorations in Urgent Publishing.4 Additionally, small, specialized publishers in Europe, which are also the most impactful, face difficulties in sustainably engaging and reaching their audiences; their current experimental approaches are isolated, and the often innovative technological tools and distribution methods publishers implement are neither shared nor replicated by their peers, preventing them from having broader, lasting impact.

Throughout its two years of existence, the Expanded Publishing Consortium has proposed to explore a few key actions to address these challenges. The project explored the development of different publishing formats that can be carefully designed to complement and expand a book’s thematic focus, incorporating feedback from audiences and peers to enhance and sustain its impact. The project aimed to build context around individual publications, organizing, for example, DJ parties, live streams, and interview sessions with publishing experts and invited guests—as done by NERO for its multi-format Ammasso events, and by INC for its The Void experimental broadcasts5—as way to provide an additional layer to a book’s content. Additionally, the consortium has been working towards establishing an expanded publishing toolkit that offers a scalable, adaptable, and replicable operational model across the publishing industry. The toolkit seeks to promote more inclusive knowledge-sharing within the publishing community, focusing on tools and practices that can continuously scale through a larger consortium. The toolkit is produced using alternative tools such as Reduct, a video-editing tool that allows collaborative work with AI-powered transcription, and Etherpad, an open-source tool that enables real-time collaborative text editing with version control, similar to GitHub, and supports multi-output functionalities from the same initial document, both materializing as a website and a ready-to-print PDF. The toolkit is published with versioning in mind; instead of culminating in a single publication moment at the end of the process, Etherpad allows multiple publication moments throughout the process (e.g., raw transcription, commented version, responses, etc.), accommodating different temporal scales in the publication pipeline.

And yet, open-source tools address only part of the problem. The Expanded Publishing Consortium project aspires to explore how books can also reshape the ways cultural stakeholders can work together. What was in Chimeras an experiment in distributed cognition can, in the context of Expanded Publishing, be scaled one level up. Unlike a network consisting only of artists and authors from different areas of research and expertise, the Expanded Publishing project involves federated stakeholders with different professional capacities in book publishing: small presses, reading communities, and self-publishing initiatives, but also contemporary art centers, nonprofit organizations, research institutes, and university departments that use the book format to disseminate their work, consolidate their audiences, and maintain an institutional memory of their activities.

According to Florian Cramer and Roscam Abbing’s discussion on the federated social media platform Mastodon, a federation, much like a chimera, “allows diverse entities to preserve some internal rules while still being able to communicate with each other.”6 With Laurent de Sutter, writer and editor at Presses Universitaires de France, we had the opportunity to work together on a confederation plan for European cultural operators that could address the acute asymmetry in cultural funding across European countries and the fragmentation of different language markets and audiences. In Belgium, for instance, publishers and other book professionals are often subsidized as part of a cultural policy that supports the ongoing professionalization of cultural workers. However, this is not the case in Italy or Greece. For smaller presses, whose business model typically involves print runs of only a few hundred copies, offset printing—a technology reliant on economies of scale—makes the production of books prohibitively expensive. This often results in small print runs with low profit margins and high break-even points, making them either outright unaffordable or forcing the publisher to rely on print-on-demand services, staple-bound Xerox zines, or risograph printing. These alternatives, however, come with their own challenges, such as restricted print quantities and difficulties in securing widespread distribution. All of this makes it a challenge for small presses and young publishing workers (such as comics artists) to professionalize. A model of federalized publishing would allow smaller presses to collaborate and produce books that may be financially unviable to produce alone.

Considering book production in a federated mode is an approach that writers such as Geert Lovink, Florian Cramer, and Silvio Lorusso, among many others, have been exploring for some time. In comics, federalized publishing is a concrete reality. Many of my own conceptual comic books, as well as Tommi Musturi’s work and that of others, are published simultaneously by several publishers across Europe. This allows publishing shareholders to benefit from government support from countries they don’t have access to it, such as Belgium’s FWB or France’s CNL. When publishing my comic books, each publisher functions like a shareholder. Publishers pre-purchase only the number of copies they can distribute within their respective territories. This model presents the advantage of sharing investment and risk among stakeholders with different budgets and audience sizes. By pooling resources, every publisher invests based on its capacity, its risk tolerance, and its expected return, not because of economic demands that are hardwired into the technical processes of offset reproduction.

A federated model of publishing also has the benefit of eschewing the myth of a mandatory, yet often rare, alignment among the network’s various stakeholders. The federation’s stakeholders do not have to strive at all costs to align with one another or to transfer expertise from one domain to another. Instead, as Schmid suggests in her discussion on interdisciplinarity, they should focus on building iterations. Referring to complex modelization processes and the expansion and development of computer technologies and simulation programs, the term “iteration” refers to the repeated application of a process or procedure to achieve a desired outcome or refinement over time. Each iteration represents a cycle of development, learning, and adjustment, contributing to ongoing improvement or the realization of a goal, emphasizing the idea of persistence through continuous effort, revision, and adaptation. Following Schmid’s epistemology of modelization, models have the capacity to mediate between different ontologies and are necessary buffer zones between theory and experience, or between experience and fact. A federation of publishers operating on different scales and with different capacities would allow for new cartographies of knowledge where non-overlapping disciplinary fragments, hypotheses, and other research ingredients from different disciplines could be put into play in a rich cognitive setting. By establishing a relative disciplinary cohabitation, a federation of publishers would be positioned to address fragments and bodies of knowledge in a horizontal fashion, while remaining totally independent from the formation and the institution of these very same disciplines.

For publishing projects where publishers want to keep a relative independence in the production process, i.e., maintain their own design and reproduction pipeline, a federated network can be operational at a higher level in the conceptualization of a publishing project. Federated publishing, involving stakeholders from various countries and languages, could address a significant shift in the translation market; in the humanities, the emerging value of having one’s book translated into multiple languages represents a notable change in market dynamics. For many acclaimed writers and authors, reaching broad, multilingual audiences increasingly offers more cultural significance and prestige than simply releasing another book on a university press, and in English. With the saturation of English-language publications, the true scarcity now lies in the ability to connect with diverse linguistic communities globally. This new emphasis on multilingual reach highlights the importance of cultural resonance. Embracing a federalized model consisting of cultural operators situated in different language markets allows publishers greater leverage to collectively access writers they would hardly be able to approach alone. It also allows them to disseminate their work across different regions, reinforcing the demand for unique, localized content that resonates deeply with readers in a multitude of cultural settings.

Two years later, the book Chimeras, much like the genetic outlier of its title, never quite saw the light of day in the usual sense. It never hit bookstores; it certainly skipped the fanfare of a grand launch and dodged any hint of the promotion so necessary for the life of a book. Chimeras wasn’t even granted a lowly mention in the newsletter of its supporting organization (the Onassis Foundation), despite having a corporate media powerhouse supposedly at its beck and call. Instead, the book found its true calling as a corporate gift, quietly nestled away like a tiny embarrassing secret, never quite escaping the cozy confines of the organization’s storage facility. While it did wonders for tarnishing the editors’ reputations and casting doubt on how seriously a large organization regards the community of artists and researchers who contribute to it, the book stood as a bold—albeit flawed—experiment in alternative publishing. Books like Chimeras—and there are many such examples—showcase the benefits of collaborative publishing but also provide a practical template for a federalized model in a highly asymmetrical landscape of national contexts and cultural policies. As the publishing landscape continues to shift, these collaborative, federalized practices offer a promising path for innovative, scalable, and community-driven publishing.

See also Laurent de Sutter and Ilan Manouach’s federated publishing proposal →.

Chimeras: Inventory of Synthetic Cognition, ed. Ilan Manouach and Anna Engelhard (Onassis Publications, 2022).

See →.

For (re)programming, see →.

See →.

Silvio Lorusso, “Federated Publishing: Roel Roscam Abbing in Conversation with Florian Cramer (Report),” Making Public (blog), May 20, 2019 →.