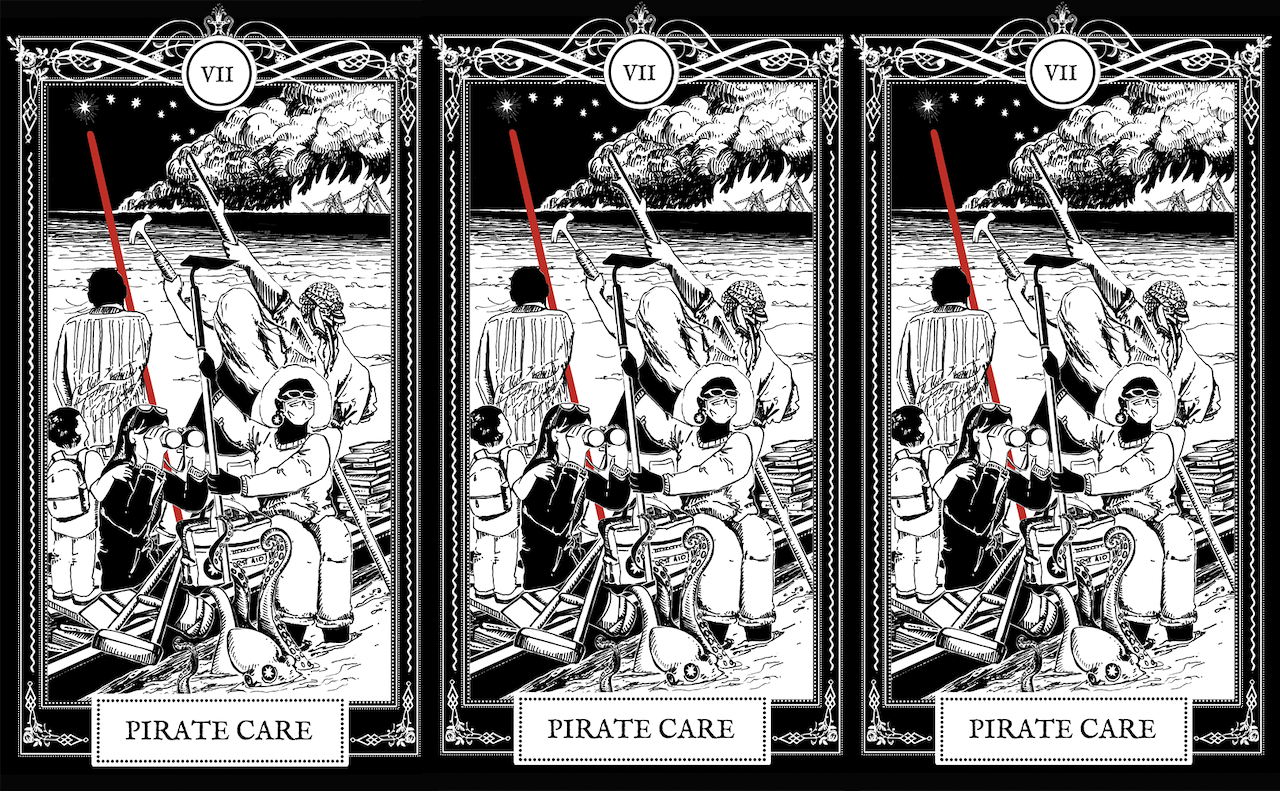

This is an excerpt from Valeria Graziano, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak’s Pirate Care: Acts Against the Criminalization of Solidarity, published this month by Pluto Press.

Amanda Priebe for Pluto Press

Empire has mobilized care as a terrain of enforcement and division. Under a regime of what sociologist Will Davies has called punitive neoliberalism, public welfare provisions are cunningly reduced and reformed to perform policing and repressive functions.1 Caregivers are tasked by their bosses to report “illegal” claimants; surveillance technologies threaten to turn every clinic and school into a border station; and unemployment, healthcare, and other insurance institutions frequently penalize people for the effects that poverty or marginalization have on them. As Angela Mitropoulos observed, the neoliberal transformation of welfare into workfare breathes life into outdated poor laws that frame the poor as morally at fault for their suffering.2 This toxic mutation of welfare infrastructures perpetuates discriminatory practices as they become more entrenched in bureaucratic and algorithmic processes, widening the gap between “deserving” citizens and unruly, undesirable, excluded “others.”

Yet, contemporary discussions of the neoliberal “crisis of care” rarely center on the worldwide attacks on solidarity, mutual aid, and autonomous care initiatives.3 In the twentieth century, societies legitimated themselves in part with reference to their inclusion of the excluded. Today, as Empire produces and then seeks to control “surplussed” populations (those dependent on capitalism for survival but not useful to that system as workers or consumers), the criminalization of care has reached a new threshold.4

Over recent years, simple acts of nourishing, protecting, and informing others have become increasingly criminalized. In Houston, Texas, activists from Food Not Bombs have been arrested for offering meals to the homeless; Spanish firefighters who risked their lives to save refugees from drowning have been put on trial; Italian librarians have faced suspension for refusing to ban children’s books that tell stories of same-sex families and gender diversity.5 The stories pile up, and it’s not just individual acts that are under attack. Systems of solidarity and subsistence are being dismantled in ways that are less visible but no less harmful. Via Campesina, in their 2015 report Seed Laws That Criminalise Farmers: Resistance and Fightback, warned of how international laws are increasingly making it illegal for farmers to share seeds, severing the most fundamental of human connections—the exchange of sustenance. A 2018 study from Johns Hopkins University and the University of Essex, The Criminalization of Healthcare, outlines how healthcare professionals in conflict zones are being harassed, arrested, and prosecuted for offering medical care to those most in need. Amnesty International’s 2020 Punishing Compassion: Solidarity on Trial in Fortress Europe offers further evidence, recounting harassment, legal threats, and courtroom battles faced by those who have helped refugees evade death by drowning or freezing at the fortified borders of Europe. These attacks erode existing forms of care and simultaneously render it difficult to develop new kinds of organized actions. They operate through a mesh of institutions, actors, and logics, but the results are the same: an increased role for top-down rules (delivered through legal and moral parameters), embedded in algorithms and bureaucracies, and a concomitant system of surveillance and criminalization that works to threaten those who do not comply. This is the nightmare face of Empire’s matrix of control, one where “care” is synonymous with the unaccountable exercise of power.

The criminalization of solidarity is not simply a matter of what gets adjudicated in trials. It acts on the level of public affect too. It takes the form of the subtle yet persistent pressure to not empathize with the wrong people, to not get involved in the injustices we see all around us. Such pressures often produce apathy, but they often produce vicious reactionary backlash cultures as well, where those needing care are targeted.

The practices of pirate care emerge specifically against this criminalization of solidarity and help people generate the courage to disobey. Overcoming the idea that “nothing can be done” is often accompanied by a willingness to break the rules to make sure those who need care receive it. Many pirate care initiatives disobey such rules conspicuously to draw attention to the injustice of the system and to reveal the forms of repression that have become normalized (normalized in the double sense of being enforced through norms and of being rendered so normal as to be unworthy of comment). In this sense, pirate care builds on a legacy of civil disobedience, but not to make a spectacle of transgression to shame the powerful. Rather, these practices disobey in order to show that it is possible to organize care for those to whom care is denied and intervene where care is no longer legal. In this, they imagine new ways of instituting care, starting from the compromised realities of our tangled relations under the punitive order of Empire.

Pirate Care and Pirate Carers

Throughout our lives, we depend on the support of others to sustain ourselves—and the world in which we and future generations have to live. The rollback of reproductive rights, the imposition of austerity, and the criminalization of solidarity are all examples of how relations of care are constantly being severed and rearranged to shore up nationalism, patriarchy, and value extraction. In this context, not letting others suffer and die is revolutionary. To stitch together these relations of care in new ways that are not amenable to the state, the market, and the family is prefigurative of a world beyond Empire.

We propose pirate care not as a distinct definable protocol but a concept to help those already involved and those looking to get involved in defiant practices of solidarity find one another and discover a common vocabulary for what we are doing in myriad ways. Unlike the institutions of Empire’s matrix of care, the strengths of pirate care are its multiplicity, plasticity, opacity, and capacity to adapt to local conditions, contexts, and opportunities.

Still, we contend that organized acts of disobedient care constitute a political formation that is more than the sum of its constituent parts. We join many radical thinkers in insisting that social and ecological reproduction will be the crucial theater of struggles to come. Pirate care is a frame within which to observe corresponding forms of militancy and to make new alliances. By federating together various forms of disobedient care, we can build our capacity to break free of Empire’s failing care regimes and grow autonomy in social and ecological reproduction, creating a virtuous circle that fosters new insurrections. Our understanding of federation is inspired by anarchist ideas of alliances between decentralized and nonhierarchical groups from which no one is excluded, as well as the examples of democratic confederalism in Kurdish Rojava and in Zapatista territories.6 We understand the act of federation as starting from different realities we inhabit to come together in order to overcome the shared structural conditions of Empire that undermine collective human and nonhuman survival, thereby creating different trajectories into a liberated world.

This vision requires different ideals and models than the ones we often associate with radicalism. Pirate care practices have a way of asking more of who we are, and on whom and on what we depend. Pirate care, as a radically feminist proposition, is an ecology of practices where the figure of the carer is also the cared-for, and where interdependence is a core tenet.

Many of the contemporary militant imaginaries on the left are still animated by the ideal of the heroic combatant on the barricade. But in contrast to the images of exuberant, youthful radical militancy we inherit from the 1960s and 1970s, with their optimism, joy, and rage, pirate care unfolds in a more melancholic ambiance, one marked by exhaustion, anxiety, and depression, and one where we must admit our dependence on oppressive systems. Thus, seeking out other predecessors, we turn to the legacy of two defiant archetypes: the pirate and the carer.

Pirate carers are hybrid militant figures. They reconcile the virile heroism of working-class militants with the consistency of feminists sustaining community organizing. Their affective politics finds its nourishment in both spontaneity and organization, in both the boredom of cleaning toilets and the thrills of delivering a rousing public speech, categorically refusing these (gendered) divisions of labor. Pirate carers often tell stories of their politicization starting from a moment of transgression in the face of an unbearable injustice stemming from institutionalized negligence and harm. Pirate carers give themselves permission to be in the world otherwise, to appropriate and share knowledges, tools, and techniques needed for their task, even if these must be stolen from the master’s house. As pirates they recognize that they always navigate the enemy’s waters with extemporaneous maps. The stultifying ethics of the professionalized care industries—codes of behavior like medical deontology or corporate responsibility—keep us locked in a moral cage, where prescriptions of “good” and “right” serve to maintain oppressive structures unchecked. Instead, we embrace a pragmatics of pirate carers: those who work in the messy, queer, and radical spaces where care grows not from compliance to protocols, but from tender, rebellious acts of collective survival.

According to anthropologist David Graeber, pirates of the Golden Age (roughly 1650–1730) and after can be credited with creating the most militant form of transcultural plebeian literature.7 They created myths about themselves and their adventures to inspire terror and awe among the imperial upper classes, but also to keep open a space for the imagination. In word and deed, pirates were living legends of how societies could be organized otherwise at a time when European empires were expanding their project of plunder and enslavement around the globe. Most pirates were proletarian sailors who mutinied, or enslaved people who liberated themselves. They were known to include women and people of no gender who escaped punitive societies. Pirates often formed renegade communities that were monstrous to their enemies, rebelling against empires and experimenting with radical care among themselves.

If the pirate was the nightmare of those empires, then the contemporary pirate carer can likewise be seen emerging as today’s Empire begins to crumble under the weight of its own violent contradictions. In claiming ourselves as the descendants of pirates, we don’t want to romanticize them: we want to use them not as moral but as political inspirations. In the name of their survival and enrichment, pirates of the Golden Age sometimes contributed to imperial systems of colonialism, slavery, and patriarchy. But we want to focus on their attempts to live, love, and survive outside the confines of imperial control, insisting on a life against a regime of death-for-profit.

In invoking the pirates, we do not want to hold them up as heroes to emulate, but as predecessors of our lineage of mutiny. For people like the authors of this book (who are spared the violence of racialization, who have European passports, who do not live in poverty or in constant fear), pirates, partisans, plebs, and freaks are the opaque figures that give us a repertoire to help build our own strategies of mutiny and betrayal. Their persistence in refusing to be put to work by Empire, striving to not perpetrate the same violence out of which they were constituted, goes hand in hand with their capacity to imaginatively open up spaces subtracted from imperial logic. As one of our favorite bad teachers, Antonio Negri, taught us, the Empire under which we live today is also a totalitarian project for putting everyone to work in the service of our own misery and destruction. Against its compounded physical brutality and bureaucratic coercion, we must learn new ways of making pirates out of ourselves in defiance of the state, the market, and the family.

We claim pirates as our predecessors not (only) as swashbuckling renegades but as tinkerers with autonomous self-organization who offer us another way to see the history of care as an insurgent act. Their ingenuity, deceptive play, and self-authorization is our inspiration. No existing institution will encourage or license us to care defiantly or tell us how: like pirates, we must give ourselves permission to care. To care earnestly about something or someone, under present conditions, might often mean that we don’t have the luxury of being earnest about how we go about it. Like those pirates of old, we may use deception, myth, and rumor as our most valuable tools. Today’s caring pirates demonstrate an ingenuity that is fundamentally opposed to the ingenuity associated with self-interested entrepreneurship, which is one of the most promoted and celebrated values in today’s mainstream culture.

Since pirates are not immune to reproducing imperial violence, we need to equally embrace carers as our predecessors. We have never not been carers: care is the condition of life itself, including human life. Carers have always taken matters into their own hands and tried to change the world. In recent times, carers from whom we trace our lineage have come from autonomous feminist struggles, from women-centered community organizing, from Indigenous land protectors, from the Black fugitive craft of constructing a “homeplace,” and from transgender and queer struggles.8

This lineage shows us that care is not an unqualified good. It is not always about hot tea and hugs. Like pirating, caring is ambivalent, and it can be coercive and violent.9 Transfeminist Marxist theorists have worked extensively to show that social reproduction, with the work of care at its core, is a key terrain of struggle and therefore it should be a key dimension of our experiences of political militancy.

We need to activate the carer in the pirate, and vice versa. To be a pirate without also being a carer risks being co-opted into a regime of property, even as its enemy, opportunistically plundering the world as it is without building one that is different. To be a carer without also being a pirate risks having one’s care held at ransom by Empire and channeled into the state, the market, or the family.

Stories of militant care today are a glimpse into a global uprising of pirate carers, a force in the making, ready to claim its role in a radical, epoch-shifting revolution. The pirate carer is our political fabulation—a way of dreaming up practices that allow us to sever Empire’s suffocating grip on our lives: the soul-sapping grind of labor, the empty promises of consumerism, the quiet despair of domestic life, the disillusionment of citizenship, and the ongoing terror of war. Pirate care practices are the foundation for a new kind of revolutionary becoming—one that immanently reclaims liberated forms of life and community from the wreckage of a collapsing system.

William Davies, “The New Neoliberalism,” New Left Review, no. 101 (2016).

Angela Mitropoulos, Contract & Contagion: From Biopolitics to Oikonomia (Minor Compositions, 2013).

Nancy Fraser, “Capitalism’s Crisis of Care,” Dissent 63, no. 4 (2016).

For more on “surplussed” populations, see Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant, Health Communism: A Surplus Manifesto (Verso, 2022).

Ashley Brown, “Food Not Bombs Volunteer Found Not Guilty after Citation for Feeding Homeless,” Houston Public Media, July 31, 2023 →; Patricia Ortega Dolz, “Spanish Firefighters on Trial for Rescuing Refugees at Sea.” El País English, May 7, 2018 →; Luca Lanzillo, “La Biblioteca comunale di Todi funziona bene? Trasferiamo la direttrice,” AIB WEB, June 11, 2018 →.

Murray Bookchin, “Libertarian Municipalism: An Overview,” Green Perspectives, no. 24 (1991); Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval, Common: On Revolution in the 21st Century (Bloomsbury, 2019); Catherine Malabou, Il n’y a pas eu de Révolution: Réflexions anarchistes sur la propriété et la condition servile en France (Rivages, 2024).

David Graeber, Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023).

For the notion of homeplace, see bell hooks, Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (South End Press, 1990).

For discussions of the coercive aspects of care, see Evelyn Nakano Glenn, Forced to Care: Coercion and Caregiving in America (Harvard University Press, 2010); and Sophie Lewis, Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation (Verso, 2022).