On the occasion of the upcoming event Sergei Eisenstein’s Capital Diaries, which will take place on Tuesday, January 21 at 7pm at e-flux Screening Room (see more information about the event here), we are delighted to publish a few fragments from an extensive new selection from the Soviet director’s Capital Diaries (1927–28) by Elena Vogman, translated by Michael Kunichika, and published in the pages of October almost fifty years after the first ten page translation of a censored version of Sergei Eisenstein’s Notes for a Film of Capital in the same journal. This extended translation draws from three notebooks containing over five hundred pages of notes, images, press clippings, drawings, and diagrams, newly reconstructed by Vogman. In these diaries, Eisenstein attempts to develop his (ultimately unrealized) film based on Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.

***

The Capital Diaries offer a new perspective on the queer communist filmmaker at work.1 They reveal a fragmented Eisenstein and reflect strategies of montage that traverse the conceptual and material genesis of his notebooks in multifaceted ways: as an auto-theoretical experience; as a research method that excessively—and sometimes painfully—explores the limits of language; as an oscillation between articulation and disarticulation; as a visual diary that assembles and disassembles images as arguments in their own right.

This practice of fragmentation is central to Eisenstein’s heterodox materialism, which operates beyond the body-mind divide. His readings of Marx, James Joyce, Nikolai Bukharin, Voltaire, dictionaries of argot, and countless newspaper articles intermingle with numerous contingent observations, all of which weave into his theoretical universe. The filmmaker continuously subjects his own body to this diaristic experiment, incorporating his psychoanalytic sessions (including elements of hypnosis), his sleepless work nights, and the graphic shapeshifting of his writing. These (self-)observations are intricately intertwined with the production of the Capital film project.

The challenge of rendering this selection of Eisenstein’s writings into English is all the greater given that their grammar and syntax, which he stretched to the limits of expressive possibility in Russian mixed with French, English and German, are themselves a subject and theme of the diaries. Composed in a varied vocabulary and marked by the stylistic valences typical of Eisenstein’s prose, the notes were produced out of a methodological ambition that leads him in these notebooks (as so often in his work) to draw from a range of disciplines, the most recent developments in which he will seek to press into service to formulate his method: higher mathematics (geometry); the natural sciences, in particular “the new biology” that was popular in the 1920s; psychology; and physiology. Eisenstein combines these disciplines with excerpts from newspapers, musings on bureaucracy, ribald verse, sociological studies, analyses of plots, discussions of contemporary films, ruminations on his own films, and dissections of kinds of capitalist signification.

Michael Kunichika and Elena Vogman

***

Notebook I

October 12, 1927

It’s settled, we’ll make Capital according to the script of K. Marx. The sole formal outcome.

N.B. the clippings are notes pasted to the montage wall.

Period, period, comma, minus—

А curved face.

Groß! Eine ganze Seite ausfüllen. [Big! Fill a whole page.]

N.B. It will sound beautiful in a theoretical “treatise”!

(Entstehung [origin] … Tret’iakov wrote an account for LEF of pictures about October.2

P.ex. “At the centerfold!”

He gave an amusing parallel—how one of us (Shub, me, Pudovkin, Barnet) is resurrecting a mammoth. 3 It’s extremely apt about everyone but me. (See the corresponding page from LEF that should be pasted here). À peu près so: “E[isenstein] is a reconstructor. He orders tusks, vertebrae, etc. made of the best rosewood… . About the irony of the end and as applied to the parts for which there are no archival data.” My way of working is terribly misunderstood. Tret’iakov is too much like a T-square with its screw fastened once and for all. His movement up and down is hopelessly parallel to itself. To analyze October one needs to be an “elastic” French curve like Shklovsky. I “brought to reason” his definition: “Then at the last minute these beautifully made wooden vertebrae are thrown out and replaced with telegraph insulation cups.”4 It’s difficult to define glänzender [more brilliantly] the specificity of our treatment of historical materials and their complete contemporanization by means of impact—that replaces facts according to an associative characteristic—and thereby brings forth a seemingly “resurrected” past, which is at the same time utterly, currently active. (Material for Ausarbeitung [developing] an entire section of theory.) (Nb. In the book it will be necessary to give such a cup en gros plan [in close-up] from a good perspective—as though it were an evidentiary illustration—ha ha ha!). Movement, light, an element of action, a purely optical irritation, etc. One needs to make a montage of two pieces: one, a “skinny person,” the other “a hand.” (The other day Shklovsky reminded me that this was my position —I asked him to write about it somewhere—since I myself couldn’t make it readable.)

De-anecdotalization—c’est probablement le plus moderne de ce qu’il y a [it’s probably the most modern thing there is]. P. ex. James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is constructed in this manner of treating narrative material. It’s curious how a terrible physiological materiality of close-ups necessarily accompanies it (as it does with me). With Joyce there is physiology in the identification (constant) of smells, and of smells of decomposition par excellence. The juxtaposing element generally should have one emphasis—the physiological. Der Sinn or der Eindruck kommt durch Zusammenstellen. [Тhe meaning or the impression comes through combination.]

. . .

December 13, 1927

For a “heretical” chapter about how there is no proletarian art and how there can’t be one. What do ideas about the proletariat as a class belong to when they lack a “prehistoric” period—one of myth, of confrontations with the forces of nature, with a primitively-melodic period of labor. As a consequence—that is, of the confrontation with actually known forces on an immediate, material basis—its “creation” should have been poured into another area—namely, “social” poetry; the reconstruction of relations through “repetition” towards October. This way also includes the artificiality of the emergence of the proletariat as a class as the dialectical becoming “from the opposite,” etc.

When one speaks about proletarian methods of struggle, one never thinks about suffocating gases or super dreadnoughts but about the propaganda that corrupts the enemy’s ranks. About “red infection” going through the heads of the stage, etc.

The same should be the case in the sphere of understanding art.

. . .

Will they give me a travel passport? I’ve been waiting for a call since morning. It’s already 2:00.

My depression is terrible again. I can’t write. I can’t work.

On Saturday I received Ulysses. The bible of the new cinematography.

I want to slit the throat of the telephone. And I terrorize everyone who lives with me. It’s all very uncultured!

I think I’ll begin a “lyrical” diary soon—a tragic one!

Shklovsky tells me not to write articles but to publish the material for them. All the same they don’t understand.

. . .

In the plan for “historical materialism,” which turns to the present day (in Capital), one needs to find today’s equivalents for the moments from the past of the breaking of epochs in two. For ex., for the walkouts by weavers and the destroyers of machines one needs to show a confrontation—electric trams in Shanghai and thousands who are deprived of bread through this, coolies lying on rail—dying.

. . .

March 24, 1928

A good episode in Paris. A war invalid. A legless man in a cart who commits suicide by plunging into water. Max recounted this from some newspaper.5 What’s most important now “in life” is this—to make conclusions about the formal aspect of October.

It’s very curious that “The Gods” and “Kerensky’s ascension” are structurally one and the same: the latter is the equivalent of parts and a semantic crescendo of titles. But the first is the equivalence (of the implied) titles—“god,” “god,” “god,” and the semantic diminuendo in the material. Rows of meaning. Doubtless, these are a kind of first signs of devices. It’s interesting that these things cannot exist outside of sense and theme (for example the bridge! in October, which can work überhaupt [in general]). An abstract, formal experiment does not make sense here. For example, upon montage generally. There can be no experiment that is beyond a thesis. (Take note).

Volodya says correctly that up to the very end October was made like a second Potemkin and then there was a shift. 6 The steps of windows and the machine of war were made on the editing table. “The Gods” was finished and filmed in the period of montage.

Notebook 2

March 31, 1928

Within this notebook lays ahead the resolution of the entire ideology of the new cinematography. Thanks to the still unformulated conclusions to be drawn from October, all the customary concepts are reduced to nothing. A strong draft blows through this new, dark desert, still uncharted. It’s terrifying. Тhere’s almost nothing to hold onto. The gods and the staircase of October. The dematerialization of the frame. Fragments on speech, on words, on an image. Analysis. Analysis. Analysis. Analysis. Algebra and the system of Descartes. The historical path. Typage. Statue. Thing. Fact. Slogan. The principle of reverse unwinding. Theoretical fragments applicable to who knows what.

In the new cinematography, the slogan should take shape as a spatial phenomenon—a cine-tractate, like an abstract algebraic formula of Cartesian or polar coordinates:

It would be “beautiful” to shape the chapter about this by giving it the title: [formula]

And finishing it “spatially”: [graph]

This is the equation of the “Cassinoid” (the Cassini ovals) and their spatial (planar) tracing (c.f. Borisov’s “Foundations of Analytic Geometry,” p. 95)

. . .

“Les dictionnaires sont des plagiats par ordre alphabétique.” [Dictionaries are plagiarisms in alphabetical order.] Charles Nodier. 7

I’m as happy as a baby. In UHU there’s a question about “what word does chauvinism come from.” The answer: from “Chauvin,” which is what they called recruits in France at the beginning of the 19th century. (Sublime!) I immediately crawled over to my three dictionaries of argot for an explanation of the meaning of “Chauvin.” Found only the praises “au chauvanisme—notre dernière vertue” [to chauvinism—our last virtue] (!!!) in Larchey.8 He has an entry from 1825, the year of the creation of the Charet type of caricature: “le conscript Chauvin.” Under the influence of “liberal” ideas, laughter begins to arise: “ces éloges donnés aux Français pur les Français” [these praises given to the French by the French]. In other dictionaries, nothing. My explanation. It’s probably from chauve—bald = clipped = shaven?

Where could it be found out more reliably? Ask in Paris about argot dictionaries. Shall I write “à mon ami” Barbusse??

. . .

It’s already March 3rd. The “fate” of October abroad has already been decided.

9. (Chauvinism) At the beginning of the 19th century, Chauvin was the popular name for French recruits.

Stegreif-Komödie [improvised comedy] —Commedia dell’arte in German (consider, for example, E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Signor Formica).

4. (Off the cuff) Off the cuff means “stirrups”; the saying originally means: to do something quickly, without first getting off the horse [out of the saddle].

For the article in LEF about the “slogan”. In the United States, a book cover does not indicate the literary content of the volume but reports that it takes three and a quarter hours to read it.

(In particular:

“I know a very nice guy,” said Emil Berr, “but he has a terrible habit. Every time you ask him, ‘How are you?’ He begins to tell you how he is doing. One can’t consort with him anymore!”

There are ideas that can only be conveyed physiologically:

(back cover)

WHAT IS “COMPACT”?

You know this joke, madam? You also know the clenching motion of the hands of those to whom it is addressed? It works again and again and always looks almost the same.

Up to here—“philosophy,” and further advertisement woher es ist entnommen [where it’s taken from]:

All clippings on pp. 24–25 taken from “UHU,” Heft 7. April 1928

But there is another compact. Also clenched and firm, but tiny and fine—Khasana-Compact!

Pressed into a solid tablet, lying in delicate jars, Khasana-Compact is the most suitable powder for use outside the home. No spilling, no dusting of clothes, inconspicuous application! Khasana-Compact powder should not be missing from any purse!

Somewhere in the West. A factory where it’s possible to steal metallic parts and instruments. The workers aren’t searched. Instead the control gates at the exit are magnetic. No commentary needed.

(Max read this somewhere. It will go into Capital.)

April 3, 1928

[Pera] Atasheva’s father, who’s currently on trial for a mutual loan, was the agent for the delivery of marble steps 9

In my linguistic “debauchery” I really make use of all parallel “readings” and parallel meanings. I think this is correct in a Marxist manner. It’s unseemly to regard a single reading in isolation, outside of its series. What gives much is comparatively co-using meanings according to an entire series of one root. For example: “obraz, obrez, obnaruzhenie” [image, cut, revelation].

“Obrazovannyi.” Gebildeter [Educated]

April 3, 1928

Today is a mad celebration of my days. I’m entering a second day without sleep. During this period, I have realized the idea of intellectual attractions and the mechanics of its action. Its variety according to October. (See the special article).

The question of cinematography can be considered fundamentally resolved. I-A-’28 [Intellectual Attractions ’28] 10

Work! Work! Work!

Sensuous image.

Intellectual image.

Designation: I-A-’28 [Intellectual Attraction 1928]

How brutally correctly did I lead the section on the reflex line. Only “unconditional” stimuli are theatrical. Physiology. An associative chain (psychologism, thesis —pièce à thèse etc. [piece with thesis]) is atheatrical. Minimally admissible. An unconditional reflex hardly exists in cinema: minimally, in the purely physiological irritation of a montage transition.

Notez, monsieur, how the handwriting the spontaneously-fulminating first pages becomes systematic when clarity enters into the whole system, steady—“considered.”

The same about “stylistics.”

The entire auxiliary demagogy of rental terms––speech, word, etc.––can now go to hell. We have our own verbal equippers!

. . .

I need to search for the best term for “stimulus” (it would be good if it could replace “attraction” immediately). “Irritator,” “exciticator,” “provocator” won’t do.

During these “grand days,” there’s not even a shred of paper …

N.B. In Sokolniki these charming verses were written in a gazebo:

I was fucking

Broke my cock

Come see, dear,

How I fuck with a shred …

… I wrote that in the new cinematography the armchair of “eternal themes”

(academic themes: “Love and Duty,” “Fathers and Children,” “The Triumph of Virtue,” etc.) that will be taken up in a series of films on the themes of “foundational methods.” Today the content of Capital has been formulated: (its orientation).

To teach the worker to think dialectically.

Show the method of dialectics. This could be (roughly) five non-representative chapters (or six, seven, etc.). Dialectical analysis of historical phenomena. Dialectics in matters of the natural sciences. Dialectics of class struggle (the last chapter). “Analysis of a centimeter of silk stockings” (about silk stockings as such, Grisha noted somewhere: the battle of silk makers for a short skirt). I added: competitors, “masters” of the material of long skirts. Morale. Episcopate, etc.

It’s still difficult to think with images that are “somehow” “beyond plot.” But it’s not a calamity, ça viendra! [it will come!]

. . .

N.B. April 6, 1928. Is such theoretical wandering rational? The endless returning to one and the same proposition, premise, etc.? Of course, yes.

(Definitive) formulas still can’t be given. Everything’s insufficiently dug up. Or rather, the process of turning these premises over in my head hasn’t gone on long enough. Although we condense time firmly over these days. And being a writer, of course, is the reason for this. Unorganized—unsystematized writing—loosens things up in an extremely productive way.

For one: in the project for the article I-A-28 the process of stringing thoughts together actually brought about the concept of intellectual attraction. This article doesn’t establish a basis or a logically ideal process of substantiation. It was a record of a series of views about the specificities of the new cinema, and from them, dialectically within the article itself, all these views and concepts arose—the concept of I-A-28 brings together all these views.

. . .

Joyce can help with my intention: from a bowl of soup to the English ships sunk by England.

Further, my intention is to orient Capital toward developing as a visual instruction on the dialectical method.

Stylistically: this closed plotline, with each of its points serving as a starting point for material that’s ideologically closed, but it is materially maximally disconnected. It gives maximum contrast.

The very last chapter should give a dialectical deciphering of history, which is entirely irrespective of the theme at hand. Der größten Spreizung! [Of the broadest spread!] By which the “beautiful” stylistic organics of the thing as a whole is attained.

Of course this is entirely thinkable even without such a “chain.” (Connected entirely not by plot but ordinarily.) But in the paradoxical plan the deliberate “step backward” from the ultimate form always sharpens the brilliance of the construction.

. . .

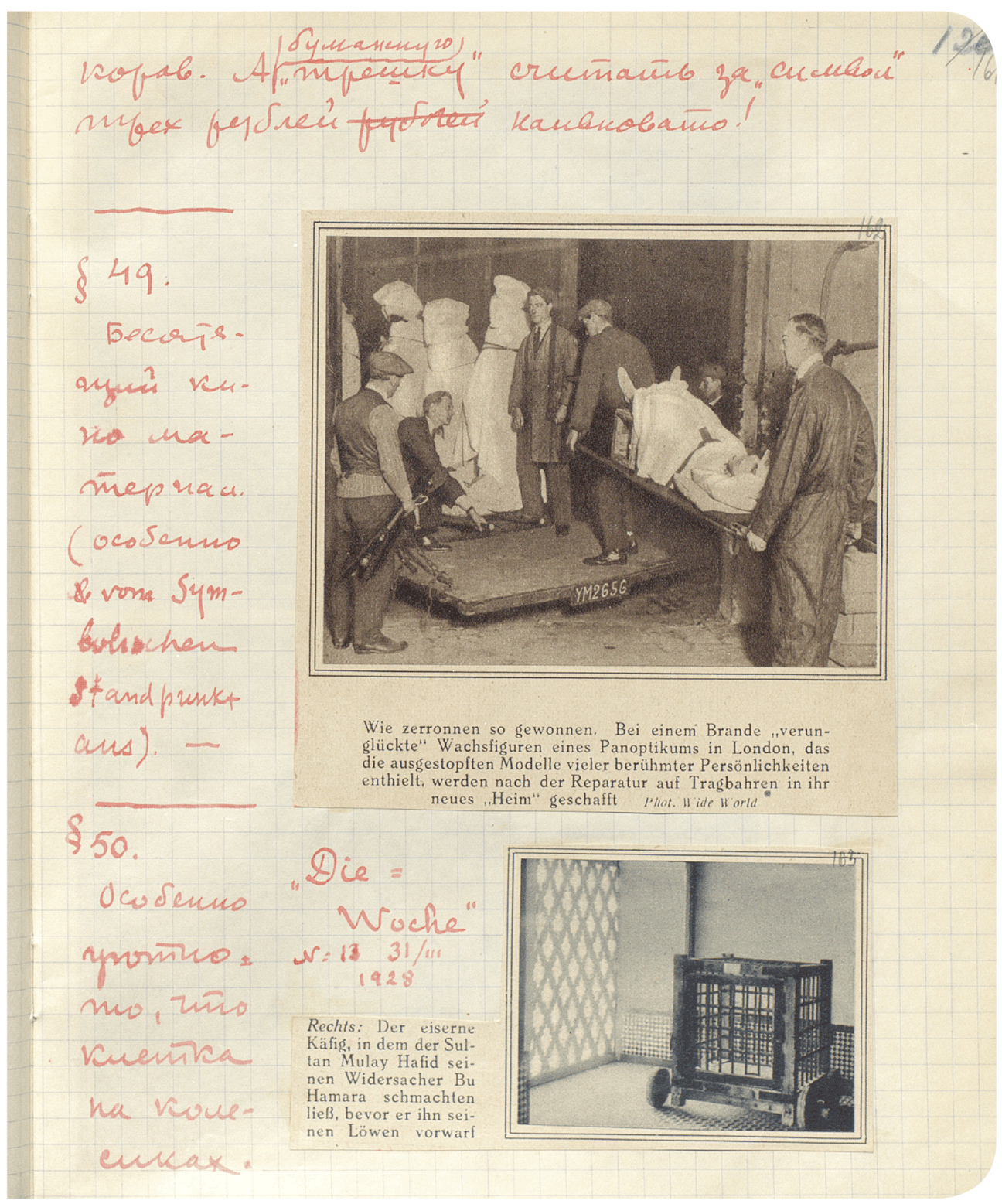

§ 49. Brilliant film-material (especially vom symbolischen Standpunkt aus) [from a symbolic standpoint] —

Wie zerronnen so gewonnen [Easy come, easy go, lit.: as melted, so gained.] Wax figures “wounded” in a fire in a London wax museum that contained stuffed replicas of many famous people are brought to their new “home” on stretchers following repair.

§ 50. It’s especially cozy that the cage is on wheels. “Die Woche” no. 13 31/4. 1928.

Right: The iron cage in which the Sultan Mulay Hafid let his adversary Bu Hamara languish before throwing him to the lions.

How American transport companies protect themselves from the risk of a strike. Mass accommodations for two thousand willing workers, who are supposed to maintain the most essential traffic in case of an imminent strike by the employees of the New York subway.

“Die Woche,” no. 13 3/31/28.

Notebook 3

§ 1. Entering into the fifth “volume” of my “diary” I feel old—old, like all those old men above, captured together.

I need periodic rest. To become young again so as not to spoil the serious pages of my outlines with lyrical digressions.

The theoretical tasks bearing down upon this volume are of paramount significance!

Right: An Easter gift from the city of Munich? Twelve old men bestowed with apostles’ robes.

§ 25. For the cutouts from AIZ on the next page.11

The magnificent theme of selling cult objects, or even better, the form of their degeneration: such as Osterhase, Eier, etc. [the Easter bunny, eggs, etc.]

One could make an entire film out of just one of these. “Tod dem Osterhasen” [Death to the Easter Bunny]. For example, one on a traditional story in a toy factory—of hares. Or in the setting of a “weaver,” in a village, where they make handicraft toys. Generally a “hare” film. Maybe some of it could be touched on in Capital, this material is so very eccentric with regard to the “given idea.”

Easter Bunnies, Easter eggs—big business around Easter

This is how they look—the preachers of Christian “charity”

But what was still faith, fanaticism or zeal and devotion to a very specific ethos many centuries ago, is today merely and exclusively politics in the interest of the ruling class: the bourgeoisie. And then, apart from politics, it is a business. Over time, entire industries that seek to profit from religious illusions—and indeed do so—with Easter Bunnies, Easter eggs, and other nice things have developed around this Easter.

One only has to look at the four frock-wearers shown here to understand that the preacher folk, these heralds of “Easter good tidings,” are inclined towards anything and everything other than the self-renunciation and human kindness called for by Christ.

A.I.Z. EASTER Volume VII no. 15 Berlin, April 15, 1928

Bondu devils of Sierra Leone. Every village there has these devils. They are dressed in strange robes of woven bast. The natives worship and fear them and attribute unlimited power to them.

. . .

§ 65. To construct the book (the volumes) analogously to the exposition of Capital—from the simplest observations and statistics to a philosophical system—that is, a concept.

§ 66. This is a good dedication: to Rudolph Bode, Ludwig Klages, Vsevolod Meyerhold, Richard Barthelmes, and my students.

§ 67. The spherical coordinates are a discovery “from the necessity of writing” something so complex. “To sell” them … mathematics. It may come in handy for the fixation of something else. Ask some mathematicians whether spherical coordinates, in fact, already exist as a concept. Then it is um so besser [All the better]. Dann kann es Erudition auf dem Kultur Bazar stehen. [Then erudition can (also) stand at the culture-bazaar.]

§ 68. Nur nicht sterben!!! Nur Zeit genug haben!!! [Just don’t die!!! Just have enough time!!!]

§ 69. Diese Tage ist es ein Leben auf alle hundert Prozent! (%!) [These days it’s life at all one hundred percent! (%!)]

. . .

Today I’m sending Bleiman a photo with the inscription:

“To Bleiman, a portrait of the head of that organ from which the seed of the new cinematography shot forth!”

(And, maybe, [a portrait of] myself in addition—dann wäre es [then it would be]—“the head and the penis head from whence shot forth etc.”

(N.B. The head of this god (from October) is clearly of phallic origin. Notez the skin pulled back into folds.)

Make the epithets bash each other’s heads / Anatole France.

Today I picked up at the Κitay-Gorod wall: Sharngorst’s “Spherical Trigonometry with application for astronomy” (1884).

The selection presented here is an excerpt from Sergei Eisenstein’s “The Capital Diaries: A New Selection” published in October (2024, 188, 25–104). It was translated from the Russian and annotated by Kunichika; translations from the German are by Matthew Vollgraff; the French is translated by by Kunichika and Vogman. The transcriptions from Eisenstein’s manuscripts were made by Maru Mushtrieva, Julia Portnowa, and Vogman, and revised by Ekaterina Tewes.

Eisenstein refers here to Sergei Tret’iakov’s “Film for Anniversary Year” (“Kino k iubileiu”), Novyi LEF, no. 10, p. 27.

Esfir Shub (1894–1959), filmmaker and film editor; Boris Barnet (1902–1965), filmmaker.

Viktor Shklovsky (1893–1984), a friend of Eisenstein’s and a critic of his prose style, as well as a leading literary and cinema theorist

Maxim Shtraukh, a friend and collaborator of Eisenstein’s on Glumov’s Diary (1923), Strike (1925), and The General Line (1929.

Possibly Vladimir Nilsen, a cinematographer who worked on October.

Charles Nodier (1780–1844) was a French author, librarian, and early advocate of Romanticism in literature.

Lorédan Larchey’s Dictionnaire historique d’argot went through multiple editions, with an eleventh edition appearing in 1888.

Pera Atasheva (1900–1965) was a journalist, assistant director, and Eisenstein’s wife.

“I-A- ’28” marks a significant moment in Eisenstein’s thinking about montage when the latter enters its “intellectual” phase.

Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung, AIZ, the Worker’s Pictorial Newspaper was a German publication that ran from 1924 to 1933.