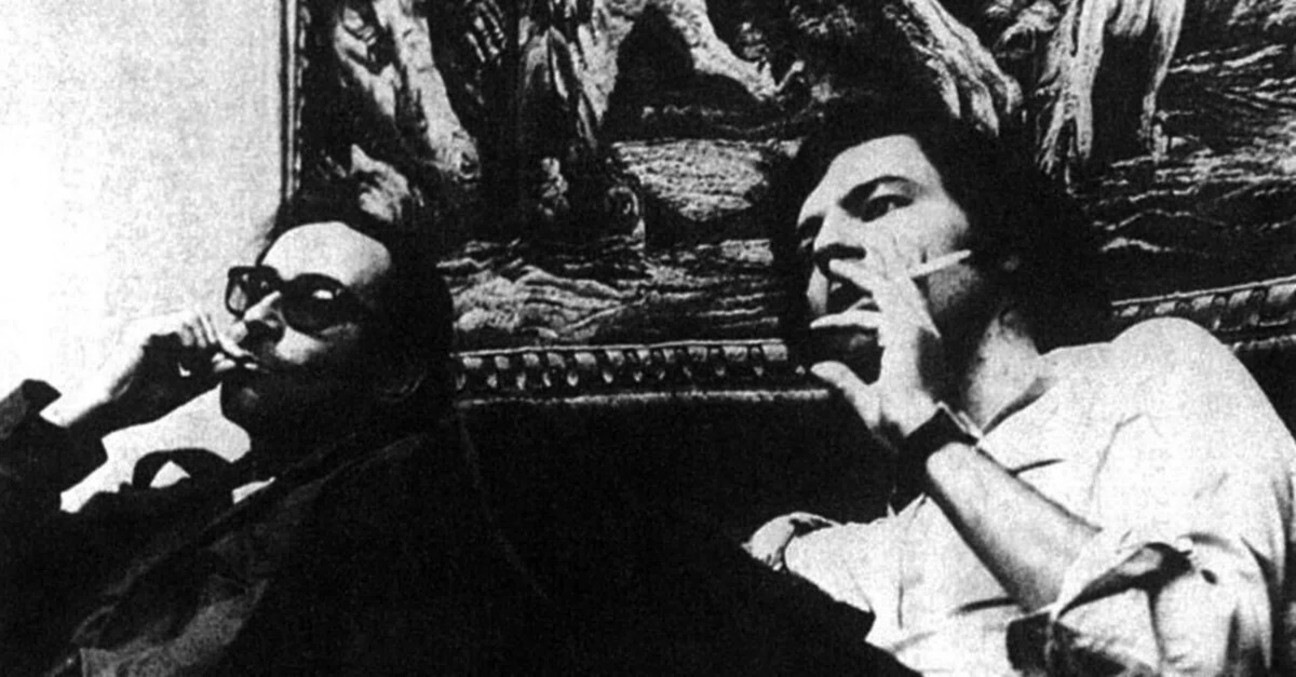

Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin

Proposal for a Tussle, was originally written as an accompanying piece to a retrospective on the essay film, The Way of the Termite: The Essay in Cinema, 1909–2004, curated by Jean-Pierre Gorin and presented at the Viennale (Vienna International Film Festival) in 2007.1 Comprised of fifty-seven films along with a series of lectures, the program extensively traced the historical panorama of the cinematic essay, highlighting its diverse formal expressions and their enduring relevance.2

The Black Hole

One could hope to go through the maze of that shop by clinging to the Ariadne’s thread of literature. That anyone would want to write an essay let alone film one is always astonishing. Like their literary counterparts, film essays seem to be here to help us understand that the subject matter is what matters to the subject. At the core of all essays is an interest in something that matters to the ones who decide to write them or to give them a cinematic existence, an interest so intense that it precludes the possibility of naming it simply and efficiently, of filming it in a straight line, so to speak. At the core of the essay is something so charged that it prompts the existential necessity not to talk about it but to talk or film around it. Without this black hole the essayist’s gait (and the gait precedes and conditions the essayist’s voice) cannot exist. And there lies the strange paradox of the essay: that in the end we will have learned less about the thing that prompts it than witnessed the declension of its importance to the one who talks about it. And in that lies the strange exchange that links the essay to its readers or viewers: we get summoned not by the thing itself but by the dance it imposes upon the one who finds the compulsion to talk about it, in words or in words, images, sounds and music. We might be indifferent to what prompts any of the fifty-seven films that compose this retrospective; but we can’t ignore the restlessness with which they dance around their own premise. The essay reveals style as a form of compulsion that matches and opens us up to our own. Hardwick, again speaking about the literary essay: “Essays are addressed to a public in which some degree of equity exists between the writer and the reader.”3 Change the word “reader” for the word “viewer,” and this economy remains the same.

The Ariadne’s Thread Cut

Yet if the reader has time on his hands, the viewer has none. On the page the argument always begs to be interrupted, read again, savored, retraced and understood anew. The literary essay more clearly than the novel or even the poem hints at the fact that readings that do not set up a second, a third, an nth repeat do not qualify as true readings. Can one read any page of Montaigne without interrupting oneself often in mid-phrase and retracing one’s steps? This stutter consecrates his writing as viaticum. We know from it that we will have to carry him in our backpack, and that we will never be finished with him. Replace the name Montaigne by the names Emerson, Hazlitt, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche or Rilke, whatever your fancy. The results will be the same: whoever pretends to read them in one sitting is either lying or confusing them with Alexandre Dumas. Films, as we know, live another life entirely. In the darkness of the theater in which they are meant to be seen, we cannot interrupt their flow, let alone retrace it. Their images are less appearances than disappearances, each inexorably leaking into another, their sounds passing to sounds. Fiction has always had an easy relationship with this flow. Its characters thrive in its temporality. Essay films, in contrast, are always in battle with their own. In an essay film, the status of an image, the status of a sound, be it a voice, a noise or a few chords of music, radically differs from the status the same elements tend to occupy in a fiction film or in a documentary. It is not that more is at stake, but something definitely different. There is linearity to the chronologies of fiction (however scrambled the order of their presentation) and to the factual exposition of documentaries (however complex the realities described) that do not put in question the nature of the film image and its flow. But a film essay seems to be endlessly engaged in operations that try to stop or divert this flow and redirect it upon itself. The image in an essay film never passes through; it revisits itself, and it resists its own temporality and passing. This resistance can take the form of an untouched recurrence or a reframing by sound. The success of a great essay film may well be its thousand and one ways of resisting time, of delaying it. Scheherazade dwells in the palaces the film essayists build.

Scheheradzade, Engineer

The essay films are thus condemned to playfulness. Their need to delay pushes them constantly outside of themselves. Film fictions and documentaries are dreams of concentration and coherence, whether achieved or not. The space in which they unfurl is always dense. They are sedentary and praised for it. Film essays are engaged in other sets of operation altogether. They are nomadic and often looked upon suspiciously because of it. For them, dissemination is the rule, and the building of ever-opened networks of associations always imposes itself as their ideal. Fictions and documentaries tend to nail it down, while film essays tend always to riff on it. Invention is not necessarily the rule of this game. The essay film does not labor toward the creation of a sui generis image as do fiction and documentary. It feels perfectly at ease quoting, plundering, hijacking, and reordering what is already there and established to serve its purpose. And it feels perfectly at ease doing that twice or three times over, so that the same elements switch into new configurations. It is the rhizomatic form par excellence, forever expanding and finding no better reason to stop than the exhaustion of its own animating energy. The essay is rumination in Nietzsche’s sense of the word, the meandering of an intelligence that tries to multiply the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or by which it has been elected). It is surplus, drifts, ruptures, ellipses and double-backs. It is, in a word, thought, but because it is film it is thought that turns to emotion and back to thought. The strange thing is that as such it flirts with genres (documentary, pamphlet, fiction, diary … you name them) but never attaches itself to one. It flirts with a range of aesthetics but attaches itself to none. It is, in both form and content, unruliness itself, “termite art” and not “White Elephant art.” I am, of course, borrowing from Manny Farber, and borrowing wholesale. Listen to Farber, and forget he might just be speaking about Laurel and Hardy, as the words stick even tighter to the film essayists: “They seem to have no ambitions toward gilt culture but are involved in a kind of squandering-beaverish endeavor that isn’t anywhere or for anything… . The most inclusive description of [their] art is that, termite-like, it feels its way through walls of particularization, with no sign that the artist has any object in mind other than eating conditions of the next achievement.4

Termite(s)

Let’s take a few steps Du Côté de Farber. It is common for all who analyze the essay form to insist that without an I there is no essay. It is, of course, in the domain of evidence. And yet it mucks up the field. The autobiographical, the diaristic, the confessional that come with the pronoun do not necessarily an essay make. And to take a step back and tag the essay film to a persona that would appear in filigree of the utterances of an I does not necessarily help either: the field fractures itself along the lines of a typology endlessly refined. Let me risk a hypothesis. What seems at work here in this invocation/celebration of the I is a pusillanimity that does not want to separate the film essay from its laurelled literary kin. The advantage of bringing the Farber quote into the debate is that it takes the I out of the equation and aggressively replaces it with the instinctual energy of a bug that prompts generally more a call to the nearest exterminator than the celebration of an aesthetic. And what if after all the essay film gained its stripes, its independence from this unsightly association? What if we had essay films less for the fact that a nominative singular pronoun spoke in them and less for the fact that a type of persona could emerge as a watermark of that discourse than for the fact that in certain films an energy engaged and redefined incessantly the practice of framing, editing and mixing, disconnecting them from the regulatory assumptions of genres? The tentativeness of the film essay would be then only accessorily the tentativeness of a soul confronting itself with the world to become the tentativeness of a practice confronting itself with the system of rules and regulations that shape it, and questioning them. The film essay not as illustration of the endless shimmer of the soul and a delivering of everything “a prancing human voice is capable of ” (Susan Sontag) but as experience of the capacity of the Id of cinema to show itself through the practice and the manipulations of filmmakers compelled to map however tentatively new territories.

The ID

Maybe in the end we should reconcile ourselves to the fact that the film essay is not a territory and that it is, like fiction and documentary, one of the polarities between which films operate. An energy more than a genre. And it might well be cinema’s last irreducible. You find it, arguably, at the origins of cinema with A Corner in Wheat (1909), but a few years later [D. W.] Griffith laments the fact that cinema has turned away from filming “the rustle of the wind in the branches of the trees.” Twenty years and ten days that shook the world pass, and you see it triumphant in [Dziga] Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929); but a few trials later you feel the Stalinist boot heavier by the day on its neck in Enthusiasm (1931) and Three Songs of Lenin (1934). You think it is done and over with when the oppressiveness of commercial cinema rules, but it reappears under the guise of [Jean-Marie] Straub and [Danièle] Huillet’s Too Early, Too Late (1981), [Chris] Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983), or [Jean-Luc] Godard’s Puissance de la parole (1988). As soon as you wonder if it is after all just an über-Western mode, it becomes Asian with [Nagisa] Oshima’s The Man Who Left His Will on Film (1977), [Kidlak] Tahimik’s The Perfumed Nightmare (1977), or [Apichatpong] Weerasethakul’s Mysterious Object at Noon (2000). And when you want to keep it there it bounces back to the Middle East or South America … This is, of course, a fairy tale hurriedly told. One fact remains though: however dire the circumstance, the essayistic energy remains alive in the margins, an Id that haunts cinema. It is never more alive than when the times are more repressive and the dominant aesthetics occupy more squarely the middle of the road. In short, it might just be a perfect time to think about it.

Envoi

And now it is time to conclude. Retrospectives are often paeans. This is anything but. It would be to betray the essayistic energy to have attempted it. Some of the films have been gathered evidently for reasons of taste, but not all of them. Some films are here for the argumentative bounce they might produce. They are lines of force that crisscross a field. They are here to provoke and to contradict assumptions. They are here to have their right to be present violently contested as much as celebrated. Risks were taken, and no apologies will be offered for the fallout; compromises were made, and they will be assumed. From the push and pull that is curating emerged something as extensive, unruly, contradictory as the essayistic energy it set out to explore. A proposal for a tussle.

This text is republished on Film Notes with the generous mediation of Yuka Murakami.

The Way of the Termite: The Essay in Cinema, 1909–2004, a program on essay films curated by Jean-Pierre Gorin included, but not limited to, the following films: Sans Soleil (1982), Tire dié (1960), The Man with a Movie Camera (1929), One Man’s War (1981), Letter to Jane: An Investigation of a Still (1972), A Diary for Timothy (1945), Chief! (1990), Perfumed Nightmare (1977), Trial (2002), Gladio (1998), Train of Shadows: The Specter of Le Thuit (1997), Je Tu Il Elle (1974), La rabbia di Pasolini (2008), From Today Until Tomorrow (1997)…

Elizabeth Hardwick, “Its Only Defense: Intelligence and Sparkle,” New York Times, September 14, 1986.

Manny Farber, Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies, exp. ed. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998).