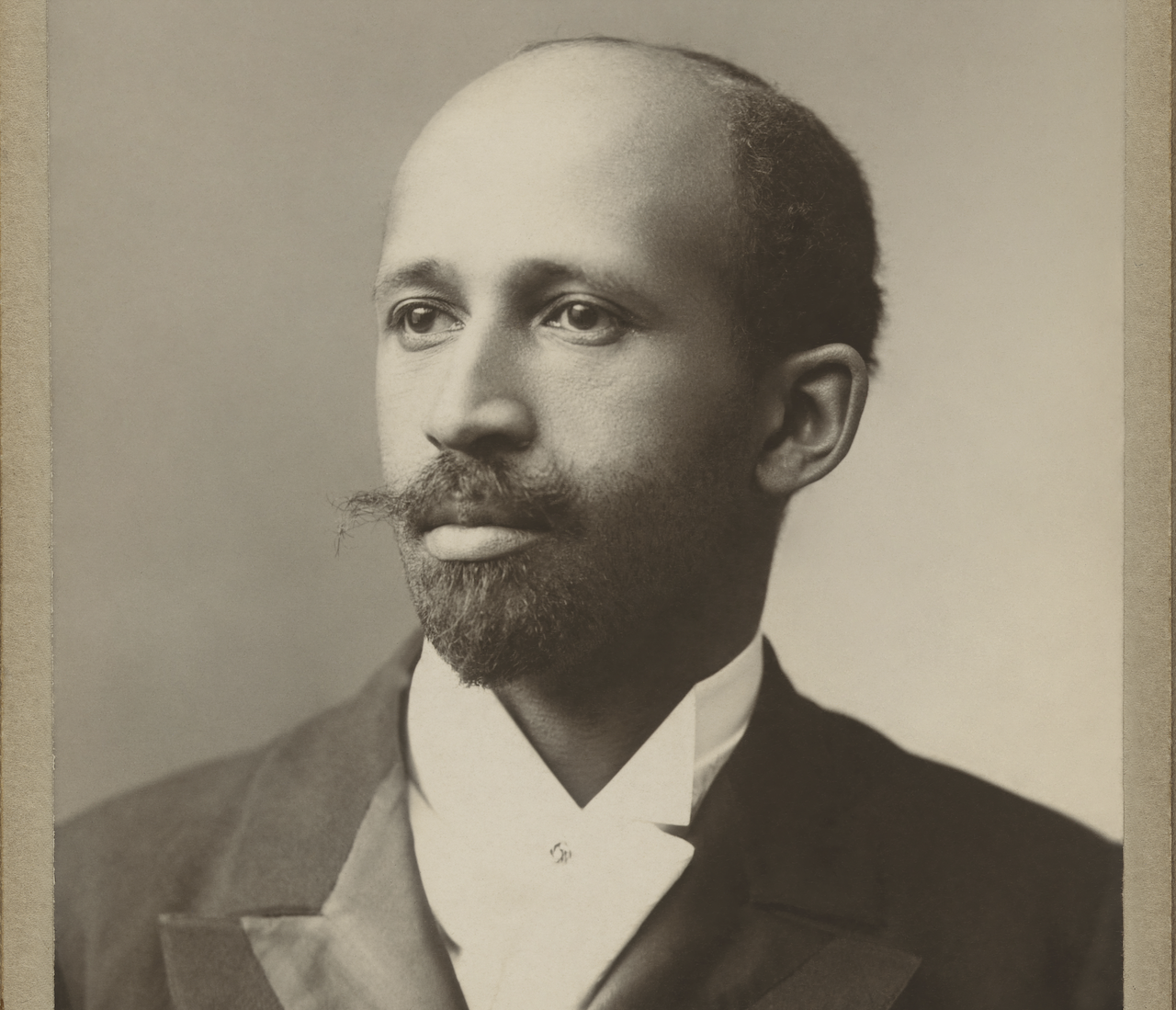

W. E. B. Du Bois by James E. Purdy, 1907.

In science, we speak of making predictions, in the sense that Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which predicted in 1915 that light bends in the presence of massive objects in the fabric of space-time, was confirmed in 1919 by astronomical observations conducted by Arthur Stanley Eddington. Economics, in its classical, Keynesian, and Marxist forms, cannot make predictions of this kind (matching formalisms or hypotheses with observations) because its foundations and modes of inquiry have never been scientific.

What separates Marx from the classical schools of his time and the neoclassical ones that emerged after his death is that he was not ignorant of this fact: political economy is, at root, unscientific. As a consequence, he devoted the last part of his life (the mature Marx) to an analysis of capitalism that, in its method, prefigured what we now call economics, distilling political economy to its essence, the economy: department one, department two, simple reproduction, expanding reproduction, and so on. (It’s not an accident that the schemes in volume two of Capital lead directly to the equilibrium formalisms of input-output models that presently dominate mainstream macroeconomics.)

From the work of mature Marx we get the strong Althusserian reading of Marxism, which dismisses early Marx as metaphysical (or humanist) and crowns the late Marx as properly scientific. But all of Marx (young and old) contains as much science as all of Smith, Ricardo, the neoclassicists, the Keynesians, and the post-Keynesians (with the possible exception of Thomas Piketty’s use of nineteenth-century European literature to determine the rate of inflation and value of government bonds during the liberal stage of capitalism). Marx critiqued political economy, now called economics, but he never escaped it. As a consequence, the bourgeois claim to scientific rigor was transmitted to the socialist claim of scientific rigor. Both were unscientific. This understanding forms the basis of Moishe Postone’s analysis of Marxism after the collapse of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the triumphant declaration of the “end of history.”

We must now introduce the concept of configuration space. The meaning and function it has in physics is not entirely alien to the way I apply it to economics. It is a culturally constructed space that determines what can and cannot make the transition from the virtual to the actual. Or, to use the language of Leibniz, a space where what is possible (the actual) emerges from strictly defined compossibles (the virtual). (Deleuze was correct to see the virtual and actual as equally real.) As with physics, the configuration space of an economy presents the observable features of the system. But whereas the former relates to nature, the latter relates to culture.

Had economics, which is a combination of the neoclassical school and the neo-Keynesian school (the latter should not be confused with post-Keynesianism, which is a blend of Marx, Joan Robinson, and Michał Kalecki), examined the configuration space of American capitalism as it is—meaning, scientifically—then it would have included hypotheses such as W. E. B. Du Bois’s “psychological wage.” First proposed in 1901, and confirmed by actual events (not to be confused with real events) in the configuration space of American capitalism, it’s been completely ignored by economists on the right, center, and left.

China Mieville, who is not an economist, and so has next to no influence on mainstream commentators and pundits, does mention the psychological wage in A Spectre, Haunting: On the Communist Manifesto. He recognizes it as a confirmed hypothesis because his reading of American culture is scientific (science fictional, which amounts to the same thing). Meaning, it can make recognizable predictions.

Mieville writes: “Arguing against any optimistic faith in an ineluctable tendency towards working-class unity—such as the Manifesto can be read as evincing at times, and which remains tenacious—Du Bois sternly diagnosed racism as a key and powerful countervailing pressure.”1 Mieville goes on to cite this lengthy quote from Du Bois:

The theory of laboring class unity rests upon the assumption that laborers, despite internal jealousies, will unite because of their opposition to exploitation by the capitalists. According to this, even after a part of the poor white laboring class became identified with the planters [in the US South after the Civil War] and eventually displaced them, their interests would be diametrically opposed to those of the mass of white labor, and of course to those of the black laborers. This would throw white and black labor into one class, and precipitate a united fight for higher wage and better working conditions.

Most persons do not realize how far this failed to work in the South, and it failed to work because the theory of race was supplemented by a carefully planned and slowly evolved method, which drove such a wedge between the white and black workers that there probably are not today in the world two groups of workers with practically identical interests who hate and fear each other so deeply and persistently and who are kept so far apart that neither sees anything of common interest.

It must be remembered that the white group of laborers, while they received a low wage, were compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage. They were given public deference and titles of courtesy because they were white. They were admitted freely [to various restricted amenities and milieus] with all classes of white people.2

The point of Mieville’s short essay is: How can one understand American capitalism if it does not include this hypothesis (the psychological wage of whiteness), which has been confirmed again and again? Its absence from economic theory makes it even more shocking than the presence of dark matter in physical theory. At least physicists know nature is influenced by a form of matter that can’t, at present, be detected. Economists are so unscientific that they can’t connect the behaviors of the object of economics, capitalism, to something that is outright observable: the psychological wage, which is actual as well as real/virtual (meaning, it’s a compossible of a capitalism actualized by the American experience). Indeed, the reelection of Donald Trump can’t be explained without the concept of the psychological wage.

Those who claim that Du Bois’s economic concept is of no consequence because it is not exchangeable like a conventional wage have the same unscientific frame of mind that characterizes economics. Even Marx’s “socially necessary labor” suffers from this defect, as it assumes, for the most part, that the reproduction of labor has the wage as its source of power. Currency, in this theory, is the same as ATP, the molecule that stores and carries energy in living cells. But the key commodities of capitalism, in all of its defining stages (Dutch, British, American, Chinese), have had little to nothing to do with utility and biological reproduction. They are instead luxuries: tea, coffee, chocolate, spices, tobacco, sugar, single-family homes, cars, shark fins, and so on. This understanding of the capitalist economy has its leading theorist in Noam Yuran, whose book What Money Wants: An Economy of Desire identifies the massification of luxuries as the core feature of a system whose conatus is growth without end.

“Socially necessary labor” has an end, and therefore cannot adequately explain the behavior of its object, capitalism. Yuran can, with his radical genealogy that begins with the work of a philosopher, Bernard Mandeville, whom Adam Smith wasted no time attacking in the founding document of political economy, Wealth of Nations. Smith wanted bakers, butchers, and brewers as the image of the market, not carriages, castles, and exotic delights. Marx doesn’t even bother to mention Mandeville, though his theory of the fetishism of commodities, developed in volume one of Capital, is incomplete without The Fable of the Bees (we don’t fetishize porridge; we do fetishize tulips and automobiles).

The same goes for the psychological wage, which is also known as white privilege. A theory of it is incomplete if it’s not identified as a commodified luxury. No, you can’t eat it. No, it’s not a use value that, in contrast to exchange value, reproduces, in Marxist economics, labor power. But it is exactly the same as a single-family home—a mansion massified, a luxury commodified. To be white is to be like the elite, which in the Antebellum South represented the closest thing America had to a European aristocracy. This is its power. This is why a criminal is returning to the White House.

China Mieville, A Spectre, Haunting: On the Communist Manifesto (Haymarket, 2022).

W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America (Harcourt Brace, 1935), 700–1.