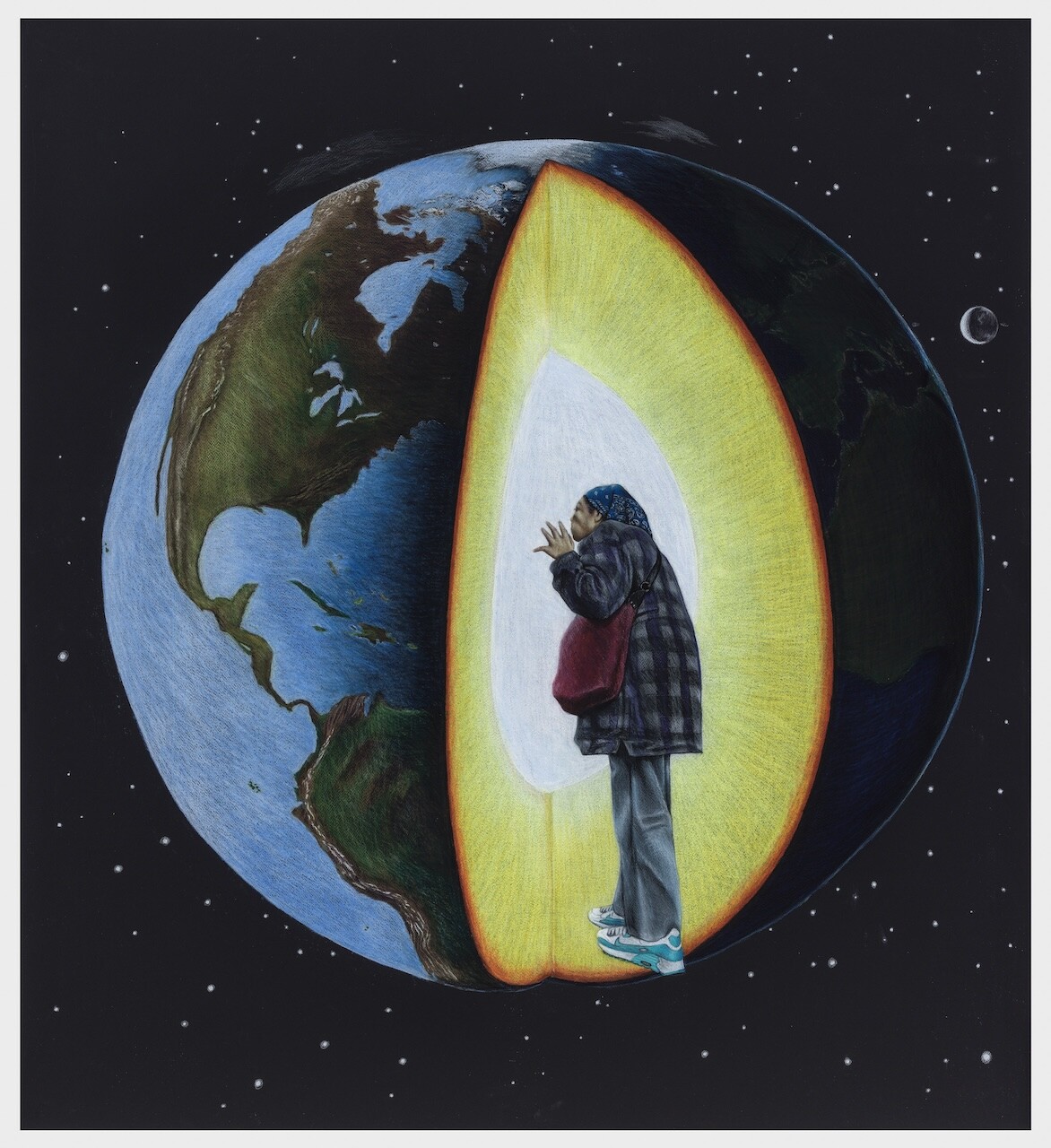

Shellyne Rodriguez, In Pursuit of Humility (2023).

At the end of July, artist Shellyne Rodriguez convened a discussion with Molly Crabapple and myself at P.P.O.W. Gallery to accompany the exhibition “Airhead.” Curated by Eden Deering and Timmy Simonds, the show exhibited works by artists committed to pedagogy. The conversation was informed by three “Ds”: dispossession, diaspora, and doikayt. The latter of these terms is the Yiddish word for “hereness,” a central concept for the Jewish Labor Bund, a transnational socialist Jewish organization founded at the end of the nineteenth century. As summarized by Frank Wolff, they “saw twin repression as Jews and as workers … [and] called for revolutionary activism in the places of inhabitance by creating and fostering a revolutionary and socialist Yiddish workers’ culture.” He continues:

Doikayt was a double-edged concept. On the one hand, the Bund neither opposed nor favored emigration … On the other hand, carried forward by thousands of activists, Bundism and a Bundist presence unfolded “in other streets.” This means that doikayt was possible everywhere. The diaspora had its centers of gravity, but was not spatially confined. By practice rather than by design, Bundists developed a transatlantic (and later global) Jewish socialist network.1

As Shloyme Mendelson wrote in 1948 to describe the brutal methods Zionists used to suppress Jewish dissent: “What a bitter irony that after the utter destruction brought upon the Jewish people by Fascism, the latter’s methods of terror are now triumphant in Jewish life … It is as if the slaughterer had infected his victims with his germs during the slaughter.”2

An attention to hereness is where one might begin to contest and ultimately undo the projects and logics of dispossession (the second “D”) fundamental to state-building and nationalist logics. As Rodriguez reminds us, this engagement with the local context is a key task of any diaspora, the third “D.” Writing recently about the way that Puerto Rico is now courting new settlers with tax breaks, Rodriguez offers: “In order to shape a politic in alignment with Puerto Rican anti-colonial struggles, we must first come to terms with who we are as a diaspora in relation to the archipelago.”3 As the genocide in Gaza continues, and as late fascism’s processes continue to mutate and ensnare the present,4 attention to anti-nationalist collectivity from the past and present remains paramount.

—Andreas Petrossiants

***

Andreas Petrossiants (AP): Molly, for readers who are unfamiliar, could you introduce the Jewish Labor Bund and their notion of doikayt?

Molly Crabapple (MC): Of course. The Bund was a movement of Eastern European Jews that was born in the czarist empire in 1897—incidentally, the year that political Zionism was also born with the World Zionist Congress at a casino in Basel. At that time, the czarist empire was perhaps the most institutionally anti-Semitic place on earth, where Jews were a racialized minority who were discriminated against in all facets of social and economic life and confined to an area of land known as the Pale of Settlement. There, even if you converted to Christianity, you could not escape the “stain” of your Jewishness. Violence against Jewish communities was either ignored by the state or perpetrated by the state itself through pogroms that were used as a release valve for the anger of peasant and working-class populations. The Jewish Labor Bund was founded in Vilnius, then known as the Jerusalem of Lithuania, by a group of Jewish Marxists who realized that Jews were oppressed both for their class (as workers) but also for their ethnicity as Jews. When I read their speeches, it sounds almost like this early prefiguring of intersectionality.

Bundism opposed Zionism from the start. It banned Zionists from membership in 1901. As Zionism grew more powerful as both a political ideology and a practical movement—first with the British occupation of Palestine after World War I, and then with the arrival of over one hundred thousand German Jewish refugees in the early 1930s—Bundism kept up its stalwart and irreconcilable opposition. At first, Bundists opposed Zionism because they thought it was fucking stupid. That’s really the best way to put it. They were like: “There are nine million Jews in Europe … and they’re going to move to Palestine? To do what?” Within Jewish communities in the Pale of Settlement, Bundists also observed how rich Jewish bosses used philanthropy towards Jews in Palestine as a sop to shut up their own underpaid, exploited Jewish workers. But above all, the Bund thought that Zionism was helping racists who wanted to expel European Jews from their homes. After all, both Zionists and anti-Semites have always agreed that there isn’t a place for Jews in Europe. Bundists were like, “Fuck that. We have lived in Eastern Europe for a thousand years, and you’re not going to get rid of us. We’re here to stay.” This insistence on staying is doikayt. It’s not some fuzzy liberal concept. It’s not like: “In this House, we believe in science, value love, and welcome refugees.” No. When the Bund said, “Here where we live is our country,” they meant that “here where we live is our country, you motherfuckers, and we have guns, in case you have a problem with that.”

My great grandfather Sam Rothbort was a painter who taught my mom how to paint, and thus, taught me how to paint by proxy. Sam made six hundred paintings from memory of his hometown Vaŭkavysk in Belarus. One of them that I was obsessed with growing up depicts this woman in a little corset with Gibson Girl hair. She’s wearing a long skirt and throwing a rock through a window. Her boyfriend is next to her holding more rocks—because on date night, you do not let your girlfriend carry her rocks. It is titled Itka the Bundist Breaking Windows. That was the first thread that led me to discover this party to which my great grandfather belonged, which fought to overthrow the czar and to make a multiracial socialist democracy.

The Bund took part in the revolution of 1905 and fought on the barricades in the cities of the Pale of Settlement. To diffuse the tumult, the czarist empire issued some petty-ass concessions that didn’t really add up to anything, and then blamed Jews for the revolution. Mass pogroms broke out that killed thousands of Jews in cities like Kyiv and Odesa. Twelve years later, the Bundists were back at it. They took part in the revolution that overthrew the czar in 1917, but soon afterwards, they got kicked out by the Bolsheviks, because the Bolsheviks did not like other socialist projects. They reconstituted in independent Poland.

Somehow, in between the wars, Poland was even more racist than the czarist empire. At one point, the government of interwar Poland wanted to colonize Madagascar to ship all Jews there, and failing Madagascar, they were committed to exiling all the 3.3 million Polish Jews to Palestine. And in this country—where there are constant violent pogroms, where there is state-backed discrimination, where there is segregation at universities, where there are violent marches with bombs being thrown while Polish nationalists screamed “Jews to Palestine”—it is in this country that the Bund staked their claim of “hereness.” And that’s what makes the whole ethos of doikayt so singular: here, where we live, in this flawed, broken, fucked-up place with people who might hate us, here, even if “here” is hell, this is our country, and this is where we have a right to be.

And they did it with so many of the methods that the Black Panther Party later used. Everything from networks of community care (like communal soup kitchens and clinics) as well as armed militias that defended against evictions, protected unions, and fought off racist attacks. Meanwhile, the Polish government was funding Zionist militias in Palestine, providing guns and military training to the Irgun and the Haganah militias in Palestine during the Great Arab Revolt. Throughout the twenties and thirties, the Bund condemned Zionists for working as handmaids of British imperialism and for conspiring to strip the Palestinian Arab majority of their land and their political rights. They published books against Zionism, went on lecture tours, issued resolutions against Zionism and all other forms of nationalist “chauvinism,” as they called it, and brawled with Zionists in the streets.

AP: Thank you for that history Molly and for bringing it to the table for us to consider in the present. In a recent essay, Shellyne, you call for all diasporic groups to meaningfully engage with their places of struggle, work, and everyday life, rather than attempt a project of universality that is fundamentally tied to the nation-state and nationalist projects. It is not far from the ethos of doikayt when you write that “arrivants” (as opposed to settlers) must embrace that they are part of the collective body of the disposed.

Shellyne Rodriguez (SR): Yes. For me, the question is: “How did we get here?” When I first learned about the Bund, I recognized doikayt’s meaning on a personal level: as a diasporic person myself, whose grandparents were part of a wave of coerced migration from Puerto Rico (still under US occupation); as a Black woman, who has no avenue to trace back where my ancestors were stolen from; and lastly as a person born and raised inside empire, but on its periphery in the Bronx, where my people have endured deindustrialization, neoliberal organized abandonment, police violence and murder, widespread landlord arson of our communities, and chemical warfare by way of an imported narcotics economy.

Living through these subjectivities that I embody, doikayt was something I was already practicing. Existence here on the periphery of this empire is a diasporic existence, whose origin always begins with dispossession on many scales and for many reasons including imperialism, colonialism, neoliberalism, extraction, genocide, and war. What we hold in common is the experience of dispersal and fragmentation that is the history of all enforced diasporas. The place of origin becomes charged, because as Stuart Hall reminds us, places are subject to change; they don’t remain stagnant once one leaves. The Africa my ancestors left behind is not the same Africa in 2024. The desire to return is a desire that can never be fulfilled. We, diasporic peoples, are all holding the trauma of dispossession. For the Jewish people, that traumatic dispossession is also colored by genocide. European colonization also forms Jewish history, as the atrocity of 1492 brought about the expulsion and forced assimilation of Jews and Muslims as part of the formation of the newly minted catholic nation-state of Spain.

AP: Of course, the main reason that the Bund is so little-known today is a direct result of the Holocaust and the mass murder of Jews, queer people, Roma, and communist militants by Nazi Germany. Molly, could you expand on the Bund’s anti-fascism?

MC: During the Nazi occupation of Poland, the Bund was instrumental in the resistance, and helped lead the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt. But, like all of the other Jews in Eastern Europe, they were murdered. And after the war, they were systematically marginalized by three forces. They were banned by the postwar communist government in Poland. After the war, a Polish nationalist insurgency killed over a thousand Jews, often on the pretext that they were communists, but mostly because they dared to return to their homes. And finally, the Bund was beaten by Zionists, who took ruthless control over the administration of postwar Jewish displaced-persons camps in Europe, where in 1948 they imposed a draft that coerced survivors to enlist in the Haganah militia, which was conducting a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Palestinians that culminated in the Nakba. Although the Bund chugged along for decades afterwards, and still exists as a cultural group in Melbourne, they were crushed as a political force by the Holocaust, by Stalin, and at last by Zionist hegemony in the Jewish community.

I’ve spent the last five years working on a book about the Bund. I learned Yiddish and I went to many places where the Bund was active. I couldn’t go to my great grandfather’s shtetl, Volkyvysk, because it is in Belerus, but I did travel around Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine under the Russian invasion, and all over Poland. And the thing about this idea of going back, as Shellyne was saying, is that almost every bit of us Jewish people has been destroyed in those places. We have been so cleansed from most of Eastern Europe that we only exist as commemorative plaques. There are sculptures being sold in Poland right now that are like the equivalent of lawn jockeys: caricature sculptures of hook-nosed Jews sitting on piles of coins that people put in their businesses for luck. That’s what happens after a genocide.

I thought about these experiences when I was in Lydda, a Palestinian city that Zionist militias ethnically cleansed in 1948. Fifty thousand Palestinians were put on a death march. The Palmach, the main Zionist militia, murdered hundreds of people inside a mosque. I was there as a guest of the Palestine Festival of Literature. While we were being given a tour by a scholar from Zochorot, a joint Jewish-Palestinian group that commemorates the Nakba, this war criminal–looking motherfucker comes up and starts screaming at the scholar who’s lecturing us about what the Zionist forces did to Palestinians during the Nakba. Looking at the man’s belligerent atrocity denialism, all I could see was the psychopathy of Eastern European nationalism imported to Palestine.

SR: Colonization is the linchpin for modernity, ushering in wounds that are still being nursed today as Black and Indigenous peoples continue to face new iterations of genocide, imperialism, and colonization. The understanding of dispossession cannot be uncoupled from these processes. But this is not the case for those dispossessed Zionist Jews who saw colonization and imperialism as the antidote to their genocide and the remedy to their dispossession. The Zionist movement, thus, appears as a new iteration of the crusading conquistador or the pioneering manifest-destiny buckaroo, repeating atrocities, but against the Palestinian people this time. The Zionists have not solved the problem of their own dispossession, they’ve just exacerbated it for themselves and for the Palestinian people.

Dispossession is irreconcilable. This is the deep wound. We are unable to return to our places of origin. This is true for all of us. My grandmother left Puerto Rico in 1957. On what grounds would I now return to her neighborhood in Sabana Grande to make claims to that land? It isn’t even the same Puerto Rico. The same is true for Jewish people who faced Nazi atrocities. Doikayt was about staying and fighting to remain in Poland, Austria, Germany, Russia, and so on. There is no way back to those places, and to subsidize that desire with the colonization of Palestine in the name of an even older homeland is even farther away from reality.

AP: This reminds me of a work by Shellyne called Common Denominator (2023). It’s a colored-pencil drawing of a typical New York City steam radiator: a material exemplar of the kind of conditions that might bring different diasporas together.

SR: Totally. The piece is called Common Denominator because as organizers we are always looking for that thing that’s going to be the connecting issue, that’s going to get everybody to care long enough so that you can maybe expand collective care for each other. You know, once we’re dispossessed and displaced and we gather here, in the metropolis on the periphery of this particular empire, something like a broken radiator is the type of local condition that creates new relations. Personally, I’m always speaking from the perspective of someone from the Bronx. In my neighborhood, the Soundview-Parkchester area of the Bronx, in one building you might have a family from Ghana, a family from Bangladesh, and a family from Yemen. Or maybe the bodega used to be Puerto Rican, used to be Dominican, but now it’s Yemeni.

Activists say this thing: “Think globally, act locally.” Well, in the context of the Bronx, you end up in a situation where you can act locally and globally at the same time. Families end up here, in what my comrade Kazembe calls “the ring around the white collar,” you know? In June, for example, the Bangladeshi community was dealing with the state murder of students who were protesting the quota laws in Bangladesh. If we dial back the months to mid-February in New York City, when it was below freezing, you might share a wall with a family who is worried about the heater being broken, but also concerned about their family back in Bangladesh, right? And so, you end up in a situation in which you can be thinking about that and perhaps also be in solidarity with folks who are concerned about their material conditions, which makes you into a new type of collective body inside that building. For the last year, there’s also been solidarity with the Palestinian resistance. You might meet with your neighbors to fight your landlord and take care of this radiator problem, but while you’re meeting to strategize about that, you’re also asking: What’s happening in Palestine? What’s happening in Bangladesh? So even though we started this conversation with this idea of the impossibility of return for dispossessed peoples, that doesn’t mean that there’s not a consciousness of a place somewhere else. I have no intention of returning to Puerto Rico, but there’s a consciousness about Puerto Rico and a desire to support resistance in Puerto Rico while doing what I gotta do here.

AP: In a zine cowritten by Shellyne and María Alexandra García titled “Ungrateful Immigrants: Towards Liberation and Against Imperialism,” they discuss how people arriving as immigrants to empire need not be grateful:

With papers or not, we must withdraw from collaborating with the imperial project of the United States by never forgetting that we are NOT here to sustain the economy of this empire. Here, they exploit us, and steal our wages. We recognize that the stealing of wages is not considered a crime because the laws are made for and by the bosses. We are not proud to labor here. We are ungrateful. Somos mal agradecidxs. We also don’t need your welcome to come here and work. We will come anyway. We recognize that we DO have the power to fight back by withholding our labor power alongside our other neighbors.

This connects with the Bund’s thinking in many ways—not least of which is the history of how Bundists in New York, Buenos Aires, and elsewhere took part in local labor organizations upon arrival, like the shirtwaist unions in NYC, to name one better-known example.

MC: The idea that any wall or border can stop the human need to move is pathetic. This earth belongs to us all.

I think about a form of social housing in New York called an HDFC, which provides some of the rare working class housing in this city. It came out of the eighties, when landlords were literally burning down buildings for insurance money. There was a movement primarily of Black and Puerto Rican mothers who organized to get control of the buildings from these delinquent owners. In some cases, tenants were able to buy their apartments for maybe one hundred dollars apiece. These tenants might have been really different from each other, they might have had a lot of beef with each other, but it didn’t matter. What mattered was getting their homes. Every bit of effective organizing starts with the realization that you’re all stuck together. Even if you hate each other. Even if this person plays obnoxious music, or you can’t stand the sight of that one’s face. We’re all stuck together on the same earth, and we have to carve out possibilities for flourishing and freedom together, against the necrophiliac late-stage capitalism that we live within. And that can only start by realizing our commonalities as well as our distinctness.

SR: This makes me think of Malcolm X. When asked why he chose a new last name, he remarked that he could never know his father’s father’s father’s father’s true name. Thus, the X holds not only the memory of the atrocity and the incitement for Black liberation, but also an abolitionist future of becoming something else. This is what the diasporic experience is and what I think doikayt helps us conceive of: a hybridity, shaped by difference as well as similarities and constant change. We live it here in the metropolis as we brush up against each other and are forever changed by those encounters, good and bad.

What if we too accepted this “X” as a placeholder of the irreconcilable atrocities of imperialism, colonization, white supremacy, and genocide which shape the present? What kinds of potentials exist when we accept the reality of the tragedy and take stock of who “we” are now? What if we withdraw our allegiance to empire and the nation-state? What if we put our efforts towards ending the Western imperial project that is destroying us all, and begin to imagine and collectively implement something new, something that thinks with the land and the nonhuman, and that centers the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island who are still relegated to living in reservations? What if we, as this collective body of dispossessed diasporas, seriously heeded the call to struggle in solidarity alongside those Indigenous peoples still fighting to remain in their homes and on their land against the insatiable appetite of capital and climate catastrophe?

Frank Wolff, “Globalizing Doikayt: How the Bund Became Transnational,” Italian Journal of Polish Studies, no. 13 (2022).

Translated by and cited in Molly Crabapple’s forthcoming book on the Jewish Labor Bund.

Shellyne Rodriguez, “Diasporic Pitfalls: Puerto Rico and the Irreconcilability of Colonialism’s Aftermath,” Funambulist, no. 54 (July–August 2024): 11.

See Alberto Toscano, Late Fascism: Race, Capitalism, and the Politics of Crisis (Verso, 2023). In light of the recent election results, we should sit with Jasper Bernes’s question: “Who needs fascism when you’ve got democracy this good?” Jasper Bernes, “Fascism Late, Early; Fascists Now, Then,” Brooklyn Rail (September 2024) →.