Andrea Fraser

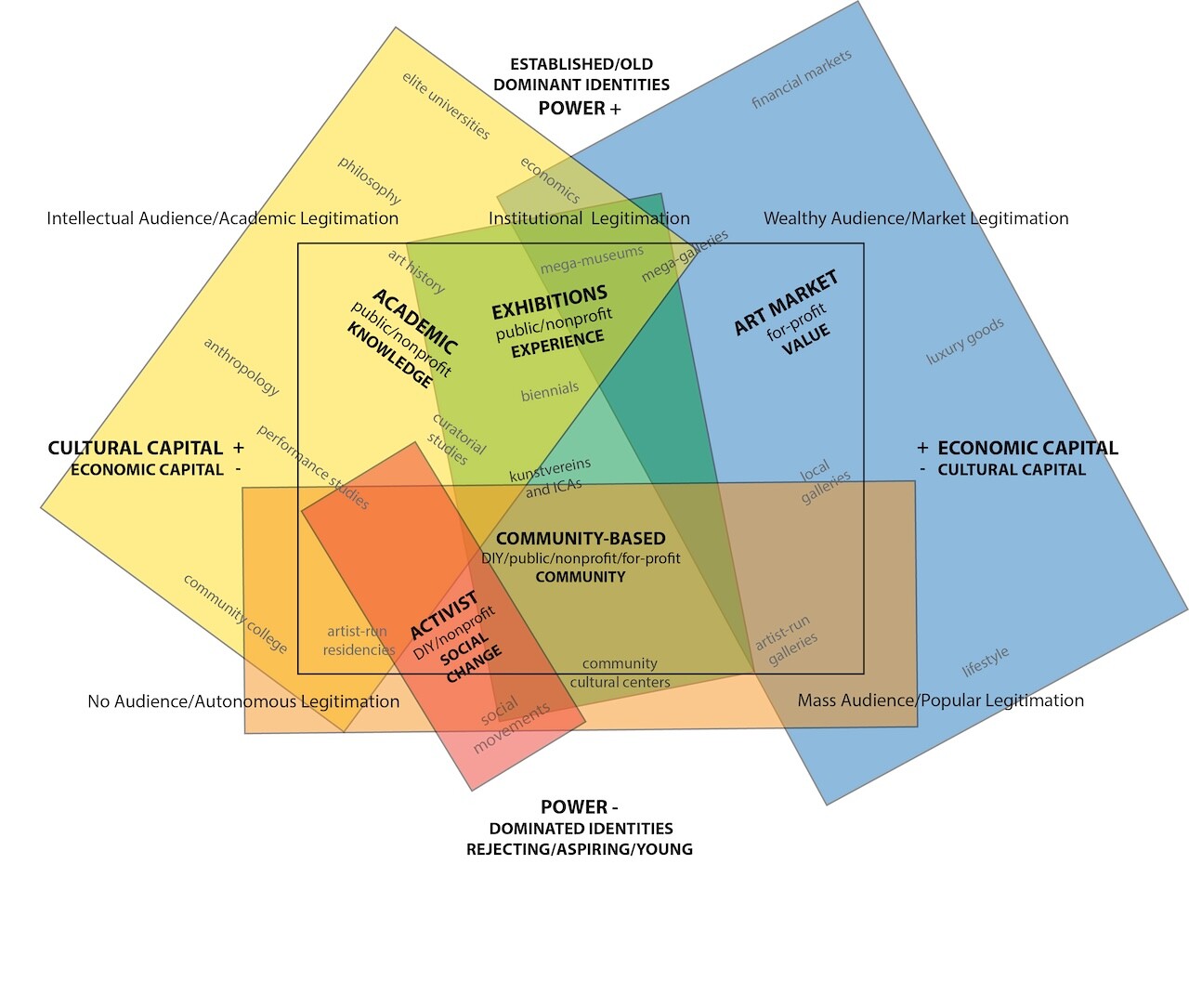

These days, whenever I meet with art students for the first time, I invariably find myself pulling up my diagram of the field of contemporary art. Sometimes I’m trying to address their confusion about the art world. More often I feel that I can’t productively engage their work and goals without first clarifying how and where they are positioned in the field.

The diagram represents the field of contemporary art fragmenting into relatively autonomous subfields. These include the art-market subfield, the exhibition subfield, the academic subfield, a multitude of community-based subfields, and the field of cultural activism. While these subfields overlap to varying degrees, they operate with and within fundamentally different economies, discourses, practices, institutions, and social spaces. They hold different criteria for the valuation and evaluation of art and effectively impose distinct definitions of what artists produce—of what art is and does. My diagram maps these subfields within coordinates developed by Pierre Bourdieu to locate fields of cultural production within social space and relations of power structured by the distributions of different forms of capital.

I began thinking about the field of art in terms of increasingly autonomous subfields almost fifteen year ago. The exponential growth of the art world since the mid-1990s is often framed as a process of geographical expansion and integration driven by neoliberal globalization and wealth concentration. However, this expansion was enabled, more broadly, by the power of contemporary art to capture an extraordinary range of investments: not only financial investments from private, public, and nonprofit sectors, but also the aspirations and energy of growing numbers of people drawn to the field and the possibilities it promises. And this expansion was also enabled, ironically or not, by radical avant-garde and political negations of aesthetic, disciplinary, and institutional boundaries, which created the conditions for art’s extraordinary expansive capacity and incorporative power.

Starting in the mid-1990s, the expansion of the field of art unfolded in three successive waves of growth. The late nineties saw explosive growth in the number and size of museums and exhibition platforms and the emergence of a field of curatorial discourse and practice within a globalizing cultural experience economy. The early 2000s saw a surge in the number of commercial art galleries and art fairs and the emergence of art as a financial asset in which the booming class of “ultra-high-net-worth individuals” could sink their surplus wealth. Following closely on these developments was a surge of art-related degree programs, from curatorial and museum studies to arts administration and management to art business, art criticism, art theory and, finally, the flood of studio art PhD programs spurred by the Bologna Process in the European Union. These developments, among others, represented not only broad expansion but also the consolidation of different segments of the art field in distinct institutions and social spaces, in ways that established specific discourses, practices, and economies within them.

The fragmentation of the contemporary art world into relatively autonomous subfields may represent a new phase in the history of the field of art. When the progenitor of the contemporary art field first emerged in Europe, it was defined by aristocratic and ecclesiastic patronage and largely heteronomous conditions of production. The emergence of the bourgeois art market in the seventeenth century separated sites and processes of production and consumption, creating the economic and social conditions for artists to work as autonomous producers. In the eighteenth century, Enlightenment philosophy and then the Romantic reaction to industrialization developed symbolic systems in which aesthetic experience and artistic creation were constituted as ends in themselves. In the nineteenth century, these social and economic conditions and symbolic systems enabled the development of modernist and avant-garde art as relatively autonomous fields of cultural production, which Bourdieu characterized as fields capable of imposing their own norms and values within their boundaries, to the exclusion, above all, of political norms and economic values.1 After World War II, the institutionalization and colonial and postcolonial extension of modernist and avant-garde art fundamentally transformed the conditions of its autonomy, even as the aesthetics, ethics, and politics that emerged from that autonomy continued to define its discourse and practices. These developments intensified systemic contradictions that rendered the field of art a structurally conflicted social space, marked by extraordinary wealth, power, and privilege at one extreme and by radical contestation and critique at the other. By the 1970s, these contradictions were themselves increasingly exposed to contestation and critique, revealing the elitist, classist, patriarchal, colonial, Eurocentric, and white-supremacist underpinnings of modernist and avant-gardist autonomy and narratives of aesthetic revolution. Nevertheless, up to the end of the twentieth century, most participants in the field of contemporary art continued to contest the same institutions, narratives, and symbolic and material resources—contestation that was itself one of the determining qualifications for participation in the field and one of the primary motors of its reproduction. This is no longer the case.

Today, the consolidation of art’s subfields has produced distinct arenas of discourse and practice and has defined distinct stakes within their specific material and symbolic economies. Competition over the distribution of these stakes seems to have overtaken any significant contestation of their definition. What once might have been relations of struggle between these subfields, or over the values that define them, now appear to be relations of mutual dependency, if not parasitism. It is the mutual dependency of art’s subfields, above all, that holds the field of contemporary art together and each of its subfields within it.

In the early 2010s, the subprime mortgage crisis, the global impoverishment imposed by neoliberal austerity, and the widespread uprising against wealth concentration seemed to bring the art field to a breaking point, revealing the yawning gap between art’s social and material conditions and its legitimizing discourses. At that time, I saw the fragmentation of the art field as a means to escape its structural contradictions and to preserve some vestige of autonomy from market forces. In an essay linking the art market to wealth concentration, I called on artists, curators, critics, and art historians to withdraw their cultural capital from the art market so that the latter would split off into the field of luxury goods, “with what circulates there having as little to do with art as yachts, jets, and watches.”2 A few years later, as an official candidate for the artistic directorship of Documenta 14, I proposed an exhibition that aimed to move the process of fragmentation along—and to work against what I saw as the regressive role of survey exhibitions like Documenta, which routinely bring together practices “developed within radically different arenas, creating a superficial continuum between positions that are completely incommensurable in terms of their values, aims, and conditions of production and distribution.” To the jury in Kassel, I proposed an assembly of discretely conceived exhibitions, each representing different art subfields and explicitly articulating their criteria and values in order to confront and contest each other across space of Documenta.

Returning to these perspectives ten years later, I can no longer call for fragmentation in the name of artistic autonomy. If I once imagined that the fragmentation of the art field might relieve me of feeling painfully split between its conflicting values and hierarchies, the consolidation of its subfields has revealed the degree to which I’m the product of those conflicts and may have no place in spaces that resolve them. If I once imagined that splitting off the market subfield might save artistic autonomy from subjection to financial values, it has become clear that art’s other subfields have embraced other instrumentalities. What forms of “artistic” autonomy are there to save anyway? Aesthetic autonomy? The “generalized capacity to neutralize ordinary urgencies and to bracket off practical ends” which, in Bourdieu’s analysis, “presupposes a distance from the world [that] is the basis of the bourgeois experience of the world”?3 Or the autonomy of artists whose rejection of economic motivations and interests was historically enabled by economic, racial, and other forms of privilege? Or the artistic autonomy derived from the capacity to impose artistic criteria and competence—that is, cultural capital—as the “dominant principle of domination” within the field?4 The recognition of the contradictory, if not fundamentally classist, if not fundamentally colonial, if not fundamentally supremacist conditions of these forms of artistic autonomy has played as large a role as neoliberalism and the expansion of the market in their delegitimation and demise.

So now, from my position as a professor at a public research university, firmly embedded within art’s academic subfield, I offer this diagram not as part of a polemic but simply as a resource to make sense of a field that makes no sense; as a map for navigating subfields that tend to obscure their basic conditions in order to protect their interdependency; and as a compass to reorient studio art programs that tend to conflate incompatible and conflicting criteria, graduating young artists whose motivations are at cross-purposes with themselves and whose practices lack a sustainable trajectory. While I present it below in an objective voice, I present it as a hypothesis to be argued with and tested, recognizing that it is informed by limited data beyond my individual experiences and observations.

Subfields

The diagram represents the field of contemporary art composed of five distinct yet intersecting subfields: the art-market subfield, the exhibition subfield, the academic subfield, community-based subfields, and the field of cultural activism. Each subfield holds a distinct definition of what artists produce—that is, of what art is or does that constitutes the basis of its worth. This definition is rarely explicit but can be discerned from the practices that predominate and find support within each subfield. These are the practices that most completely fulfill the criteria of each subfield and hold the qualities that underlie that criteria. Each subfield, in turn, constitutes a specific economy in which those qualities are valued and function as a currency.

The art-market subfield functions within the for-profit sector of commercial art galleries, art fairs, and auctions. In the market subfield, what artists produce is value. This value may be described as artistic value and its appraisal may be rooted in artistic criteria derived from the histories of specific practices or mediums. Or, increasingly, following the retrenchment of modernist and avant-garde negations of material value and skill, this value may be determined by generalized criteria for the valuation of economic goods, especially luxury goods, such as the quantity and rarity of materials and of the labor invested in shaping them. In either case, the criteria applied in the appraisal of value in the market subfield always corresponds to and manifests within a framework of connoisseurship. While artistic value may be distinct from market value, the conversion of artistic value into financial value is determined by market forces of supply and demand. The art market is typically divided into the primary market of first-time sales and the secondary market of resale. It can also be divided into individual and institutional markets, which tend to exist as distinct economies, especially for mediums not acquired intensively by individual collectors or subject to market competition and speculation, and which have limited secondary market exposure.5 In the market subfield, artists generate income through sales of artworks.

The exhibition subfield functions primarily within the public and nonprofit sectors of museums, galleries, biennials, and public art programs. In the exhibition subfield, what artists produce is experience. This experience may be understood as aesthetic experience, including an experience of artistic value; it may be understood as spectacle, including the spectacle of artistic value; or it may be understood as a form of social, psychological, or political experience, among others. The criteria for evaluating the experience that art produces and provides, including as the basis of selection for exhibition, is rarely explicit. It takes shape in the economies and dynamics of the exhibition subfield and its institutions. These include the discourses and practices of the curatorial field, which may lean toward history or theory or politics or connoisseurship; and they include the competition among cultural organizations for various forms of patronage, including box office and membership as well as individual, corporate, NGO, and political sponsorship. The exhibition subfield may extend into commercial galleries and art fairs to the extent that these spaces compete within attention and experience economies. In the exhibition subfield, artists generate income through fees for commissions and contributions to exhibitions and programs.6

The academic subfield functions primarily within the public and nonprofit sectors of educational institutions, including museums and other public or nonprofit art organizations to the extent that these are defined and operate as educational institutions. It also includes institutions and platforms for the production and dissemination of art discourse. In the academic subfield, what artists produce is knowledge, and art, art making, and engaging with art are considered forms of research, scholarship, or discursive practice.7 The development of the academic subfield within the field of art—as distinct from artistic subfields within the academic field—is tied to the emergence of conceptual and research-based art practice in the 1960s, the growing influence of critical and cultural theory in contemporary art in the decades that followed, and the proliferation of art degree programs since the 1990s, especially PhD programs in art practice. These developments created the conditions for the formation of an academic subfield of artistic practice itself, as a field of production and reception of art, and not only of art discourse and scholarship. The criteria for artistic research and the knowledge artists produce is sometimes explicit, most often within the frameworks of academic institutions or derived from the methodologies of an artist’s field of intellectual reference. However, attempts to specify criteria for artistic knowledge production and research tend to surface conflicts between nonart academic fields on the one hand, where authority is rooted in institutionalized academic standards, and art, where the imposition of academic standards can be seen as an attack on artistic autonomy. In the academic subfield, artists generate income through teaching, research grants, and publication and lecture fees.

Community-based subfields most often function within self-supporting or DIY economies with public, nonprofit, and for-profit support through grants, residencies, and community-based organizations such as artist-run galleries and collectives. In these subfields, what artists produce, or sustain, above all, is community, including communities of artists with shared interests or histories as well as geographically specific, politically defined, and identity-based communities. The criteria for art in community-based subfields is often the role art plays in the formation, existence, and persistence of the community itself, especially as that community may struggle against neglect, marginalization, repression, and violence. While “community-based art” is a recognized field of contemporary art practice, community-based subfields may revolve around any kind of artistic practice. Community-based subfields may, together, constitute the largest segment of the art field by numbers of participants, comprising what Gregory Sholette calls the “dark matter” of the art world.8 At the same time, they subsist in its least capitalized and institutionalized spaces. In community-based subfields, artists generate income through a mix of sales, fees, teaching jobs, grants, and other forms of employment both inside and outside of the art field, with residencies playing an increasingly central role.

Finally, the diagram includes the subfield of cultural activism, which functions most often within self-supporting or DIY economies, sometimes with nonprofit support. In this subfield, what artists produce, or aim to produce, is social change. The implicit, if not explicit, criteria for cultural activism is effective intervention in targeted structures of power. Cultural activism linked to collective action by mobilized groups or broad-based social movements may exist primarily outside of the field of art, entering the art field only to use its sites as platforms or targets of intervention. In doing do, however, it risks being misused within it as knowledge, experience, or value. Or, cultural activism that targets structures within the field of art itself may emerge from within the field of art but extend outside of it as the structures it targets themselves traverse the boundaries of the art field. As in community-based subfields, cultural activists generate income from a range of sources.

Coordinates

The diagram shows the market, exhibition, academic, community-based, and activist subfields positioned in a rectangle marked with coordinates that inform the rendering of their location, shape, and scale. Adapted from two diagrams in Pierre Bourdieu’s 1983 essay “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed,” these coordinates follow Bourdieu’s analysis of social space structured according to the distributions of different forms of power.

The primary coordinates in the diagram are marked by plusses and minuses at the top, bottom, right, and left. These refer to distributions of various forms of social power, or, in Bourdieu’s terms, capital, which he defines as “the set of properties active within” a given social universe or field that are “capable of conferring strength” or “power within that universe, on their holder” by securing access to symbolic or material resources within that universe.9 In addition to economic capital, Bourdieu identifies cultural, social, and symbolic capital as primary “species” of social power.10 The “Power +” at the top and “Power -” at the bottom represent a vertical axis of the art field as it is hierarchically structured into more or less dominant and dominated positions. As in Bourdieu’s diagrams, this vertical axis represents hierarchies in the artistic field that correspond to those in the society in which it is embedded, including all the forms of social power, or capital, that structure hierarchies in that society. This axis informs the placement, shape, and scale of various subfields according to the overall quantity of capital they capture, not according to the number of sites or participants within them.

The plusses and minuses at the left and right of the diagram focus on two forms of power at stake in cultural fields specifically: cultural capital and economic capital. They represent a horizontal axis of distributions of these two forms of capital relative to each other. This horizontal axis determines the placement and scale of various subfields according to the relative weight of cultural or economic capital in determining positions (influence, status, power, success) within them.

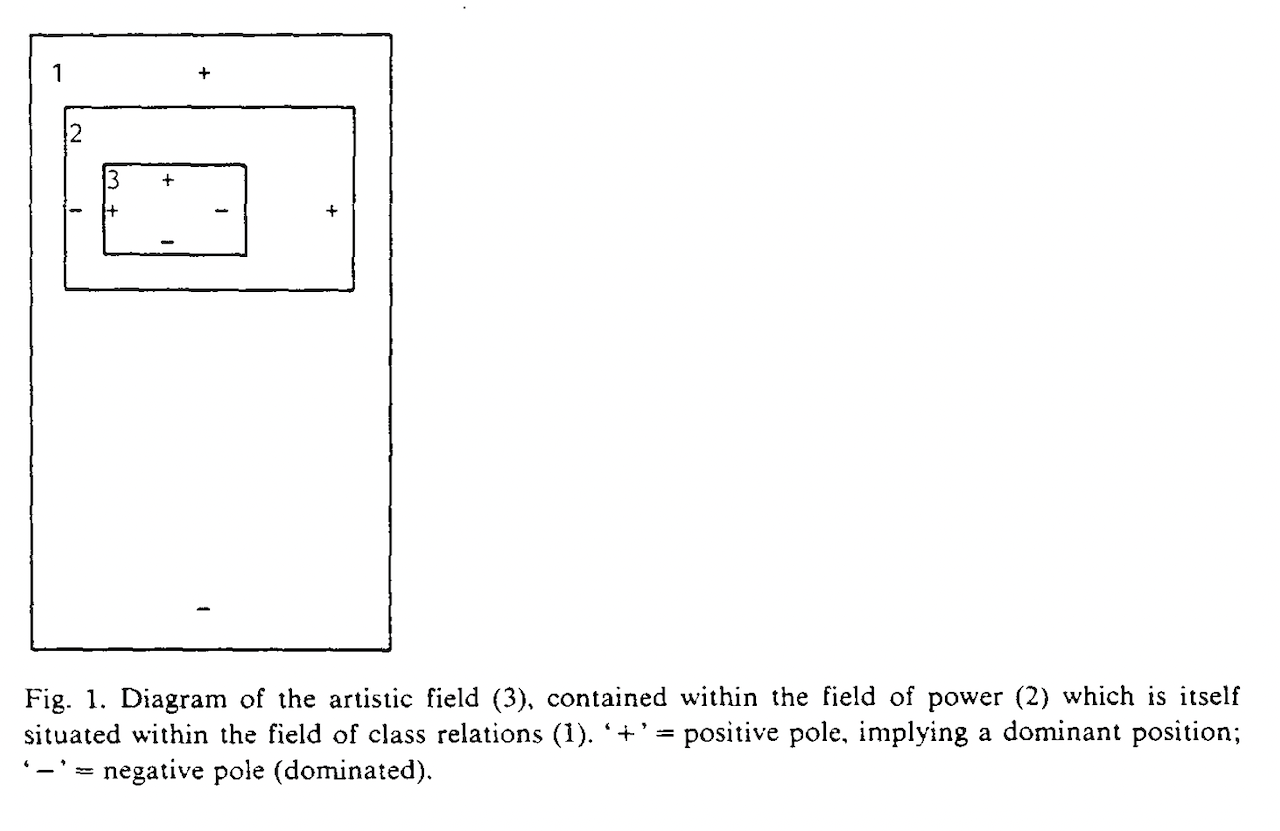

Implicit in these coordinates is one of Bourdieu’s primary points of analysis of cultural fields: that cultural fields are contained within what he calls the field of power.11

From Pierre Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed,” Poetics, no. 12 (1983).

Bourdieu developed his analysis of the field of power in a break with Marxist conceptions of the ruling class formulated exclusively in terms of economic capital and the ownership of the means of material production. Instead, Bourdieu identifies the field of power as the social space of the concentration and monopolization of all forms of social power, including ownership of cultural capital and the means of symbolic production. In Bourdieu’s analysis, the field of power is not only the site of the power that dominates the larger “field of class relations.” It “is also simultaneously a field of struggles for power among the holders of different forms of power” and over the hierarchies between them.12 In capitalist societies, in which cultural capital is subordinated to economic capital, cultural fields occupy a dominated position within the field of power. However, within cultural fields themselves this hierarchy is reversed to varying degrees, depending on “variations of the distance between the economic pole and the intellectual pole [that is, of cultural capital], of the degree of antagonism between them, and of the degree of subordination of the latter to the former.”13 For Bourdieu, the extent to which cultural capital serves as the dominant principle of value and hierarchization within cultural fields determines the relative autonomy of cultural fields within the field of power as well as their capacity to serve as sites of contestation of other forms of power within it.

In addition to distributions of capital, I adapt another set of coordinates from a second diagram in Bourdieu’s essay, which zooms in on an example of a cultural field.14 These coordinates appear at each of the four corners of the diagram and refer to different principles of legitimation— affirmation, success, prestige, authority—as these are associated with different audiences, institutions, and, in my diagram, different art subfields. In the upper left corner, where cultural capital is at its most concentrated and institutionalized, “Intellectual Audience/Academic Legitimation” marks the space of peak legitimacy in art’s academic subfield. In the upper right corner, where economic capital is most concentrated, “Wealthy Audience/Market Legitimation” marks the space of peak legitimacy in the art-market subfield. Between and above these, I have added “Institutional Legitimation,” representing long-term legitimation at the intersection of academic, exhibition, and market fields and corresponding to the role of age and time in the vertical axis of institutionalized social power.

The lower right and left corners both represent social spaces in which cultural and economic resources are not highly concentrated, or function only minimally or externally as capital. The lower left corner of the diagram represents “No Audience/Autonomous Legitimation” as the basis for legitimacy in community-based subfields. Bourdieu defines autonomous legitimation as the “recognition accorded by those who recognize no other criterion of legitimacy than recognition by those whom they recognize.”15 In this sense, “No Audience” does not represent isolation, but engagement with and by peers, participants, and community members. For Bourdieu, autonomous legitimation is one of the conditions of an autonomous field “capable of imposing its own norms on both the production and consumption of its products” and of excluding external norms and criteria of value.16 In Bourdieu’s diagram, the entire left side represents the space of artistic autonomy and autonomous consecration. In my diagram, however, the left side is mostly occupied by the academic subfield, in which cultural capital is highly institutionalized and artistic legitimacy is largely determined by the criteria of intellectual or academic fields. Here, only community-based subfields represent a potential space of artistic autonomy in this Bourdieusian sense. However, following the delegitimation of artistic autonomy in the past decades due to its entanglement with cultural elitism and other forms of domination, this autonomy is more likely to be framed as political than artistic. At the same time, in my diagram the space of community-based subfields extends all the way across the bottom of the diagram, positioning community-based subfields primarily according to volume of capital (low) rather than type (cultural versus economic). Toward the left side of this subfield, location along the vertical axis represents the degree to which cultural competence is shared within the subfield’s community and so functions as cultural capital only in a limited way or only at intersections with other fields.17 Toward the right side of this subfield, location along the vertical axis represents the degree of market integration, or lack thereof. Location along the horizontal axis within community-based subfields represents a spectrum ranging from aspiration for, but deprivation of, market success on the right, to the rejection and delegitimation of market success on the left.

Finally, the lower right corner of the diagram represents the space of “Mass Audience/Popular Legitimation.” While the left side of the diagram represents spaces in which cultural producers produce for audiences of other producers who share their specific competence, the right side of the diagram represents spaces in which cultural producers tend to produce for audiences and consumers (collectors) who do not share their specific competence. On the right side of the diagram, movement along the vertical axis reflects the degree to which the economic resources of the audience are concentrated and accumulated to function as capital, at the top, or are dispersed and expended in consumption, at the bottom. This also may correspond to the size of the audience. However, while the size of an audience defined by wealth concentration does, by definition, decrease as its wealth increases, the inverse does not hold true: the size of an audience does not necessarily grow in direct proportion to its poverty. Nevertheless, in the lower right corner, the boundary of the field of contemporary art represents the threshold between what Bourdieu calls the field of restricted cultural production and consumption and the field of large-scale cultural production and consumption. Here, the delegitimation of artistic autonomy has sprung more from the aspiration of artists and art institutions to gain some of the influence and mass audiences captured by popular culture than from a critique of art’s elitism. Here, I have been tempted to add a subfield of the internet and social media, which would touch the intersections of the community-based and cultural activism subfields toward the left, and of the community-based and market subfields—or perhaps, community as market—on the right. However, in this sense, I see social media as a platform used by other subfields, rather than a subfield in itself, even as its conditions clearly impose specific criteria on its users.

Dynamics

To describe the art market, the world of art exhibitions, the academic and intellectual art world, the worlds of artistic communities and community-based art practices, and the world of cultural activism as relatively autonomous subfields, is not to suggest that they function independently of each other. The existence of the contemporary art field as a whole, and of each subfield within it, persists largely through their interrelation and mutual dependency. Without the fields of public and nonprofit exhibitions and academia, which elevate artworks to the status of public goods and affirm their symbolic worth beyond their economic value, the art market would disappear into the fields of luxury goods and financial investment. Without the meaning and social purpose provided by the academic field and by cultural activism, the field of art exhibitions would disappear into the fields of entertainment and popular, or elite, cultural spectacle. In the other direction, without the art market, the field of exhibitions would be starved of financial resources like so many performing arts platforms in which cultural capital is not objectified in rarified products. Without the market and exhibition fields, the academic art field would lose the legions of students and scholars drawn to the opportunities they offer and much of it would disappear into the various academic disciplines from which it draws—which would in turn be deprived of important points of access to nonspecialized audiences and broader cultural relevance.

Despite this interdependency, however, the relatively autonomy of art’s subfields is evident, perhaps above all, in the different practices that predominate within them. Many artists exist in one subfield with no presence in the others. At one extreme are artists who consistently sell their work but have no professional existence or reputation outside of the commercial gallery world. At the other extreme are artists whose work is regularly exhibited, written about, and taught, but rarely bought, and then only by institutions.

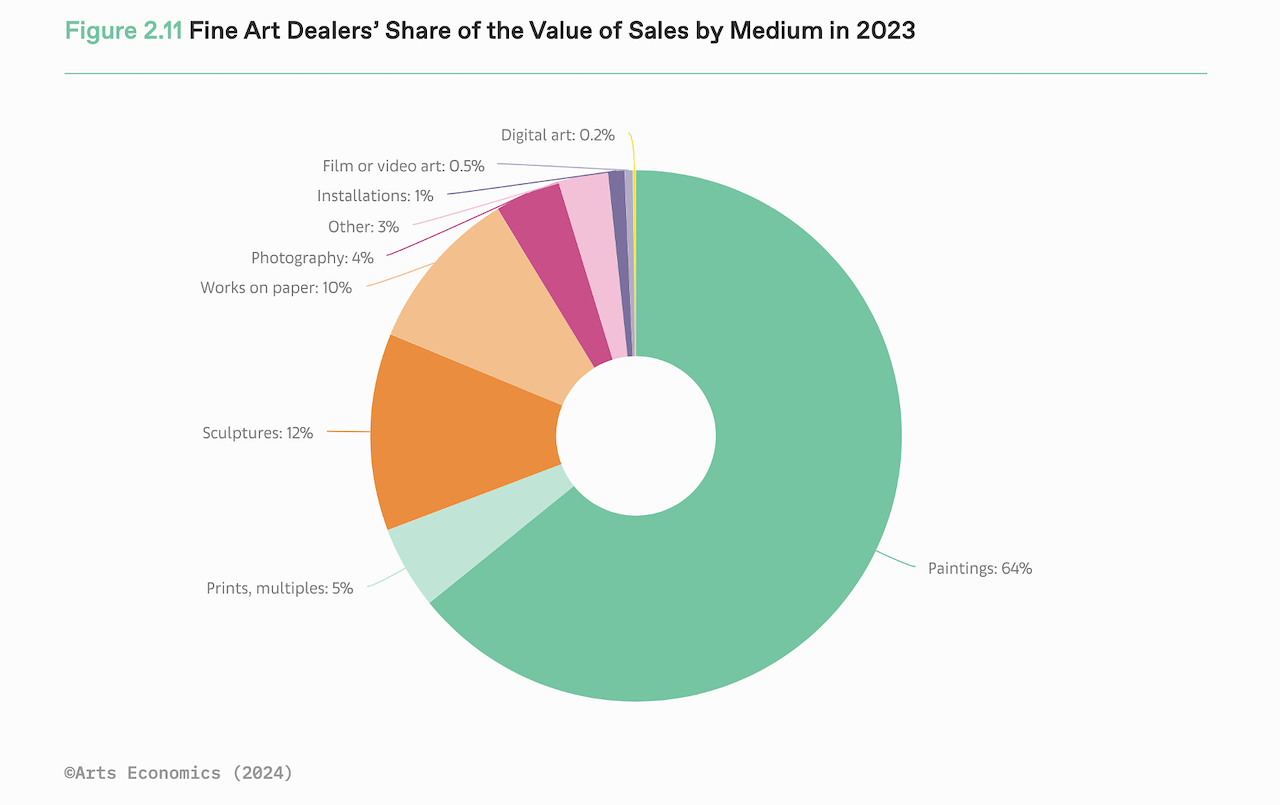

Increasingly, divisions between art’s three primary subfields are also divisions of artistic medium. According to Art Basel & UBS’s Art Market Report 2024, paintings, prints, multiples, and works on paper constitute 79 percent of the value of art sales by medium, with sculpture trailing far behind at 12 percent, photography at 4 percent, and installation and video art barely registering with 1 percent and .5 percent respectively.18 In contemporary art exhibitions, these percentages seem almost directly reversed, with video, installation, photography, and sculpture together easily accounting for a significant majority of artworks on display. The presence of these mediums in for-profit art galleries seems to suggest that they also function within the art market. What it more often represents, however, is the extension of the exhibition subfield into commercial spaces, as for-profit galleries and art fairs compete within attention and experience economies and for cultural legitimacy, which, in turn, elevates the value of artworks they do sell above that of mere luxury goods. The correspondence between artistic subfield and medium also extends to the academic subfield, which has become the primary context for performance art, social practice, and research-based conceptual practices, which have limited support in the market and exhibitions subfields except in the least capitalized spaces and programs within them.

Courtesy of Arts Economics

When different artistic mediums are present across multiple subfields, they tend to manifest aesthetics and methodologies that reflect and reveal each subfield’s criteria—criteria that become more determining with the concentration of the type of capital that underlies them. Every kind of art, from painting to video to photography to sculpture, tends to scale up in the exhibition field, and this becomes more pronounced as one moves up the axis of capitalization, as larger and larger artworks are required to fill larger and larger exhibition spaces. Within the market field, movement up the vertical axis of capital concentration corresponds not only to an increase in scale but also in production values, as the criteria for determining artistic value are more and more aligned with those of luxury goods: that of expensive materials shaped by time- and skill-intensive craft, increasingly outsourced to fabricators and technicians as efficiency in the creation of value becomes the organizing principle of artistic practices.

In the most highly capitalized spaces of the exhibition field and where it intersects with the market field, video art tends to embrace the production values and processes of Hollywood filmmaking, leaning toward narrative cinema, speculative fiction, and immersive spectacle. In the academic field, at the other extreme, where cultural capital is most concentrated, the essay-video and experimental documentary have become privileged genres for the realization of artistic research and knowledge production. Conceptual and research-based practices in the academic field tend to remain relatively dematerialized as essay-videos, performance-lectures, and text-based or data-driven artworks. In the market and exhibition fields, on the other hand, they serve to organize material production and provide art objects and experiences with content, but rarely determine their form or methodology.

It is also possible to identify aesthetics and practices that emerge at the intersections of various subfields. At the intersection of the market and exhibition fields at their peak capitalization, artistic grandiosity combines with the pharaonic vision of the billionaire class, producing an aesthetics of ambition and power and the spectacle of wealth. At the intersection of the academic and exhibition subfields, one finds models of experiential learning, embodied knowledge, and material research. At the intersection of academic and community-based subfields, communities and their practices became the agents, or objects, of research and knowledge production. At the intersection of community-based and exhibition subfields, exhibition platforms function as spaces of community and community building, often with an emphasis on interactive and participatory practices.19

Many artists work at the intersections of different subfields, creating art that reflects multiple criteria and even attempting to produce value, experience, knowledge, community, and social change all at once. From some perspectives, working across criteria may represent resistance to capitulation to any one subfield. Or it may represent the ambition to engage with more than one, for greater success or simply survival. Or it may reflect the condition of being ambivalently split between different criteria and values and social spaces. Or it may simply reflect the confusion produced by fields that tend to obscure their basic conditions in order to protect their interdependency. In any case, the circular logic of this analysis implies that the most successful or impactful practices in each subfield are those that fulfill its specific criteria most fully. At the same time, every subfield remains the site of struggle over the criteria that define success within it. In this regard, the most ambitious and influential practices may be those that succeed in redefining the criteria of their subfield, or of the art field as a whole.

Boundaries

Whenever I present this diagram, someone invariably asks if and how art can exist outside of the field of contemporary art, or how artists can exist outside of it. Sometimes these questions reflect anger and revulsion at the entanglement of art with institutions, forces, and agents of power and a direct experience of how the boundaries of the art field separate artists from other communities of belonging, especially communities dominated and oppressed by those forms of power. More often, it reflects an impulse to transgress boundaries and escape all forms of social determination—an impulse that has been central to the artistic habitus in European traditions and their globalized colonial forms since Romanticism and is a clear indicator that the person asking the question is not only firmly located within the field of art, but has internalized it.

Sometimes I share my dystopian vision of the contemporary art field as a monstrous global digestive tract that can incorporate anything and everything, passing it through the practices, discourses, and institutions of art in order to transform it into … something all too familiar. Ironically or not, the virtually limitless incorporative power of the contemporary art field was enabled by Dadaism and other avant-garde artistic and political negations of aesthetic and institutional boundaries and has been driven by artists and writers even more than by museums or the market. But the incorporative power of the art field does not imply that there are no artistic producers or products or practices that exist outside of it, or even that continue to exist outside of it after a process of incorporation, albeit in another from, for other audiences or communities.

In every direction, every art subfield can and does extend outside of the field of contemporary art into other social spaces. But there, it becomes something else.

Above the diagram and to the right and left, art subfields extend into other subfields of what Bourdieu calls the field of power. The art market merges with the field of luxury goods, from which it is separated mostly by the cultural capital it demands and by the institutions of symbolic consumption (museums and universities) which affirm art’s humanistic value and elevate it above the status of mere cultural commodities—a process that also accounts for art’s capacity to achieve exponentially higher prices than any other type of cultural good. Or the art market merges with the financial markets in which art has become an asset class, distinguished from other financial instruments mostly by its relative lack of regulation and transparency. Extending up and to the left, the academic subfield of artistic research, discourse, and knowledge production merge into the larger academic field and into the various academic disciplines from which artists and art writers derive their research methodologies and theoretical frameworks.

These and the other subfields also may extend down, out of the field of art and also out of the field of power. Here, the art market and related for-profit cultural platforms may extend into the field of large-scale cultural production and consumption, where art becomes just another lifestyle product or practice promoted by corporations and influencers. Between this extended market subfield and the exhibition subfield, for-profit museums and artist-created spectacles also reach for large-scale consumption, as do the merchandising divisions of large museums engaged in the mass marketing of rarified aesthetic tastes and experiences.

At the other end of the spectrum, activist and community-based subfields may be located primarily outside of the field of art, and also outside of the field of power, in dominated and marginalized spaces, extending into the art field in order to access its material and symbolic resources for their communities and struggles. Or they may enter the field of art as a point of access to the field of power itself, in order to contest its power from within. In doing so, however, they also become subject to its structures and dynamics and risk being used and misused within it as forms of capital to be traded in its economies of knowledge, experience, and value.

Art and artists in any form can and do exist outside of the art field—until they are written about, exhibited, and valued as art. Then they are in the art field.20 Anyone who wants to escape the boundaries of the art field need look no further than their own desire to function within it.

Politics

The sociology of intellectuals … aims at helping intellectuals to struggle consciously, which is to say without playing this kind of double game based on the structural ambiguity of their position in the field of power, which leads them to pursue their specific interests under the cover of the universal.

—Pierre Bourdieu, “From Ruling Class to Field of Power”21

Where does all of this leave the question of the politics of the field of contemporary art, its various subfields, and the practices within them? Or the politics of this analysis itself? Can this be more than just a reification of what is apparently, if not necessarily empirically, given?

If politics are struggles over the definition and distribution of the values and forms of power that structure social space, Bourdieu’s model offers a way to understand the complexity of the different forms of power at work in the art field and of the relationships among them.

One implication of Bourdieu’s analysis of the location of cultural fields within the field of power is that most struggles within cultural fields, as well as struggles waged from cultural fields within the field of power, carry a structural ambiguity, if not duplicity. They are, for the most part, not liberatory struggles against power but competitive struggles among the empowered over the nature of power and its distribution; they are not struggles between classes but struggles between what Bourdieu calls “dominant class fractions,” which serve to reproduce the “division of the labor domination” (cultural and economic, symbolic and material) more than to transform it. At the same time, it is in the dominated position of cultural fields within the field of power that Bourdieu finds the conditions for the historical tendency of cultural producers to feel and potentially act in “solidarity with the occupants of the culturally and economically dominated positions” outside of the field of power, “to put forward a critical definition of the social world, to mobilize … dominated classes and subvert the order prevailing in the field of power.”22 However, even with this structural basis, such solidarity, “based on homologies of position combined with profound differences of condition,” may produce little more than self-mystification among cultural producers while serving as grist for the mill of cultural production and for the reproduction of the art field itself.

As reflected in my diagram, Bourdieu’s analysis suggest two different vectors of political struggle belonging to two different sets of hierarchies of power. Along the vertical axis is the vector of struggles over the quantitative distributions of some, or all, of the forms of power that structure the field of art as well as the field of power and society as a whole. Along the horizontal axis is the vector of struggles over the quality of power: the relative power of different forms of power and the hierarchy among them.

In his analysis of cultural fields, Bourdieu was primarily concerned with the horizontal axis as a vector of struggle between cultural and other forms of power (especially economic power), which determine the degree of autonomy of cultural fields within the field of power and their capacity to contest other forms of power within it. In my analysis of the contemporary art field, the relative weight of cultural versus economic power still plays a significant role in structuring the field and its subfields and relations between them. However, the relations between subfields, for the most part, do not appear to be relations of contestation or even of competition over the definition or distribution of the forms of capital that predominate within them. Fragmentation and the differentiation of their criteria, values, and economies have diminished the ground on which direct contestation or competition would occur. Instead, the major subfields have developed symbiotic relationships that range from mutualistic to parasitic. The result is a field that seems to have achieved a kind of conservative equilibrium. Whatever capacity the field of art has had to contest economic power and to resist serving to legitimize its concentration seems largely lost.

While antagonism between cultural and economic power in the art field seems to have diminished in the past decades, its political significance has increased, becoming one of the defining structures of the political field. If the left and right sides of the diagram tend to correspond to left and right, or rightward,23 positions within a political spectrum, especially at an angle from the bottom left to the upper right, this may reflect not only the economic sectors in which different subfields are embedded (from autonomous to public to private) and economic class (from precarious to billionaire) but distributions of cultural versus economic capital. While neoliberalism established a complementarity, even solidarity, between cultural and economic capital, celebrating technocratic management, information industries, and global cosmopolitanism with art as its centerpiece, right-wing populism has established itself against culture as a form of social power. The far right has effectively constituted and mobilized a working class defined not by economic capital but by cultural capital, or lack thereof, while identifying cultural and “educated elites” as the primary agents of oppression, a process abetted by the neoliberalization of the political center and center left and the academicization of the far left. The result is what Thomas Piketty and others have called a multi-elite party system, in which “the ‘left’ has become the party of the intellectual elite,” while “the ‘right’ has become the party of the business elite,” and now also of low-income, low-education, and ex-urban voters who feel dominated by cultural capital and by the urban centers in which it is concentrated.24

Along the vertical axis, struggles over power within the field of art are largely competitive struggles in which the hierarchical structure of distributions of power, and its concentration, are not challenged; only relative positions within those hierarchies are challenged. With the intensifying concentration of resources within the largest museums and galleries and the ongoing neoliberal assault on the academic field, these are also, increasingly, struggles for survival.

On the vertical axis, potentially transformative political struggle would be located not within the field of art but across the lower boundary that it shares with the field of power. Here, struggles for access to the field of art against systemic exclusions imposed by patriarchal, colonial, heteronormative, white-supremacist, and other forms of identity-based domination constitute struggles to nullify their classifications and hierarchies as bases of the forms of power that define the field of power. Here, struggles across the boundary of the field of art are not a matter of solidarity across different experiences of domination but continuities in experiences of domination, and a matter of the disposition and capacity to hold membership in multiple fields inside and outside of the field of power.

Recognizing that the art field, and subfields within it, are structured according to multiple and competing forms of power, and identifying those forms of power and their dynamics, is the only meaningful way to consider their politics. So, the first question to ask of any field is: What are the criteria revealed by the practices that are supported and succeed within it? What are the values that underlie those criteria, and thus structure hierarchies of position within the field? What forms of capital, or power, do those values represent and in what social spaces and groups are they concentrated? What forms of domination do their concentration represent? Which of those values and hierarchies are at stake in struggles within the field? Are those struggles competitive struggles to gain power and position within those hierarchies, or transformative struggles to change them? What forms of power are employed in these struggles themselves and what hierarchies and forms of domination do they produce or reproduce? What new forms of social organization or principles of hierarchization, if any, are emerging in their place?

These questions can also be asked of any practice, and they can be asked of this essay itself.

Pierre Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed,” Poetics, no. 12 (1983). This essay was later reprinted in Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature (Columbia University Press, 1993).

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: The Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (Harvard University Press, 1984), 54.

Loïc Wacquant, “From Ruling Class to Field of Power: An Interview with Pierre Bourdieu on La noblesse d’État,” Theory, Culture & Society 10, no. 3 (1993): 25.

According to Art Basel & UBS’s Art Market Report 2024, museums and private institutions combined constituted only 10 percent of art dealer sales in 2023. See → (p. 103).

Activism by artists to be compensated directly for contributions to exhibitions, which gained focus in the 1990s, was both spurred by, and contributed to, the formation of exhibitions as a relatively autonomous subfield of artistic production with an economy distinct from that of the art market. My involvement with this effort included the 1994 project, co-organized with Helmut Draxler, “Services: The Conditions and Relations of Service Provision in Contemporary Project-Orientated Artistic Practice,” documented in Services Working Group, ed. Eric Golo Stone (Fillip, 2021). In 2014 the organization Working Artists and the Greater Economy (WAGE) launched a schedule of minimum fees to be paid to artists for participation in exhibitions and programs in public and nonprofit organizations. For this and other resources, see →.

What I call the academic subfield broadly encompasses intellectual engagement with art and intellectual production by artists, both inside and outside of academic institutions. I call it the academic subfield because almost all intellectual engagement with art is discursively linked to academic fields, if not also linked through educational background or employment.

Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011).

Pierre Bourdieu, “The Social Space and the Genesis of Groups,” Theory and Society 14, no. 6 (November 1985), 724.

For Bourdieu, cultural capital may be objectified or institutionalized, but exists above all in the embodied form of competencies and the dispositions and practical sense that enable their holders to acquire and maintain those competencies and to benefit from them (as capital).

Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production,” 319.

Pierre Bourdieu, “The Field of Power,” 1989, emphasis in original, quoted in Bourdieu and Loïc Wacquant, An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology (University of Chicago Press, 1992), 76, n.16.

Wacquant, “From Ruling Class to Field of Power: An Interview with Pierre Bourdieu,” 24, emphasis in original.

In this case, the “French literary field in the second half of the 19th century.” Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production,” 329.

Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production,” 320.

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (Harvard University Press, 1984), 3.

Bourdieu writes that in “the culture of little-differentiated or undifferentiated societies … access to the means of appropriation of the cultural heritage is fairly equally distributed, so that culture is fairly equally mastered by all members of the group and cannot function as cultural capital, i.e., as an instrument of domination, or only so within very narrow limits and with a very high degree of euphemization.” Bourdieu, Distinction, 228.

See → (p. 72). A 2022 survey of art collectors by Arts Economics included a breakdown by medium of collectors’ art holdings, rather than of the value of sales by dealers. The results were somewhat more balanced, with paintings, works on paper, and prints or multiples making up 50 percent of works in private collections, followed by sculpture at 12 percent, installation at 9 percent, photography at 8 percent, and film and video at 7 percent. See → (p. 74).

In another sense, community-based practice can be seen as the historical form of the market and exhibition-based subfields as their institutions took shape to consolidate and advance the culture and interests of bourgeois and national “communities.”

A social field in a Bourdieusian sense is an analytic model. It should not be mistaken for a substantive, concrete, materially existing thing. While this might be true of all such models, Bourdieu’s theory of fields developed, in part, specifically to resist the kinds of academic projections and reifications produced by empiricist social sciences, usually to the conservative effect of ossifying dynamic and contested social structures. A field, for Bourdieu, is a dynamic field of forces that both determine and constantly contest the boundaries and definition of the field itself. This may be one of the reasons Bourdieu developed his theory of fields through the study of cultural fields, in which such contestation often is explicit. Another important consequence of conceptualizing social space as dynamic, intersecting fields of forces is that social phenomena are understood to exist in multiple intersecting or overlapping fields at once. Presence or membership in a field is determined by being subject to its dynamics, whether involuntarily or by investing energy in them, energy which then contributes to the forces that constitute and reproduce the field. For Bourdieu, all fields are relatively autonomous; otherwise, they would not be recognizable as fields. However, their autonomy is qualified by the degree to which they have the capacity to impose their own norms, values, and principles of hierarchization within their boundaries relative to other fields. This also means the boundaries between fields and the conditions and dynamics of their intersection and interaction are central to the definitions and dynamics of every field. It also means that these boundaries are often the sites of intense contestation.

Wacquant, “From Ruling Class to Field of Power: An Interview with Pierre Bourdieu,” 37.

Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production,” 325.

In Bourdieu’s Fig. 1, reproduced above, the rectangle representing the artistic field is also at the left pole of the field of power, rendering it’s right-hand border something like the political center of the field of power.

Thomas Piketty, “Brahmin Left versus Merchant Right: Rising Inequality and the Changing Structure of Political Conflict in France, the United States, and the United Kingdom, 1948–2020,” in Political Cleavages and Social Inequalities, ed. Amory Gethin (Harvard University Press, 2021), 85.