Fredric Jameson

It was always a mistaken assumption that one could account for totality in a neutral, unengaged, and nonpartisan manner. Against this, already the early Marx argued that one can only conceive of the capitalist system in its entirety from the subjective perspective of those who are essential for its reproduction yet—politically—excluded from it. And the early Hegel assumed that any form of rational thought relies on positing a “totality of reason,”1 for only in this way does it comply with its own demand, namely to go to—and thus to think (to)—the end, to think “all” of it. This is the only way that thinking can remain open to what it cannot anticipate, the contingencies of real historical life. In this sense, totality “is not something one ends with, but something one begins with.”2 We can only understand the world and its history if we totalizingly assume that it can be understood, that there is reason in it. Only then we can identify the rationality of that which otherwise seems devoid of it—the rationality even of the illegitimate or the exceptionally extraordinary. This insight has often and rather harshly been contested in the last decades, but some contemporary thinkers have stuck their necks out and defended it against the critiques waged by so many that it seems (almost) impossible to list them.

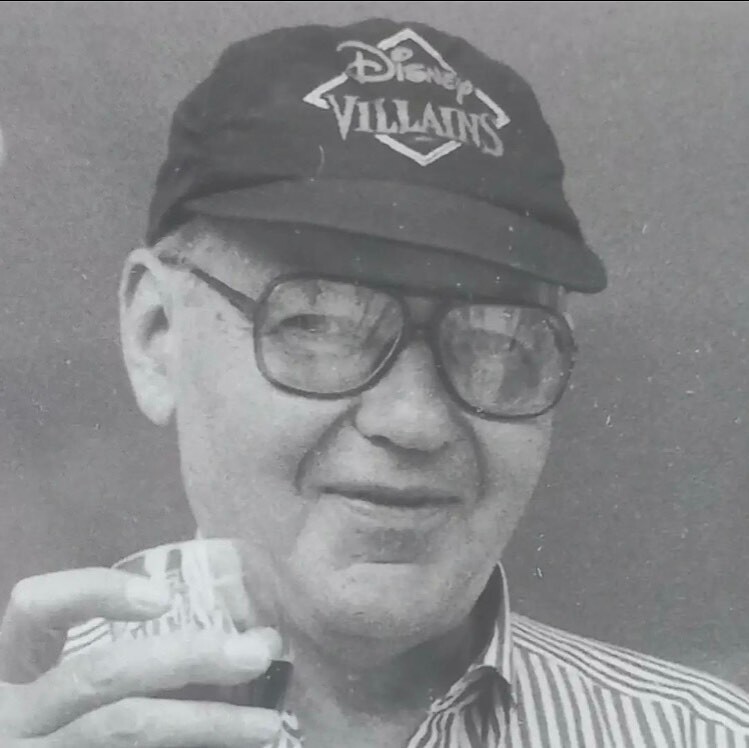

Recently, the life of one of the most significant and intellectually powerful contemporary defenders of the concept of totality, namely Fredric Jameson, came to an end. While his eulogists have praised his many great achievements, (in)famous quips, and general theoretical trajectory, I would like to formulate my own, much abbreviated, and somewhat partisan account—taking my cue from one of his book titles3—of the relationship between Jameson and method, Jameson’s method of thought. What follows is an attempt to think through the extreme richness and depths of Jameson’s work and propose an admittedly selective and condensed account that allows us to identify three key concepts belonging to the backbone of any contemporary post-Jamesonian form of thought. The three concepts I want to identify as operators of totalization are rationalism, dialectics, and orientation.

The first operator of totalization can be identified in Jameson’s powerful conceptual contribution to the concept of rationalism. This contribution is linked to his account of a phenomenon that could hardly be more contemporary, namely conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories are problematic manifestations of a rational demand, a demand of reason. This demand is a demand for orientation in a world that no longer allows for any, since the constitutive principles of its organization have become obscured. Ironically, conspiracy theories are the wrong form of doing the right and necessary thing. They are the most catastrophic way of responding to a rational cry for help. Jameson demonstrated that one can (and must) take paranoia in its conspiratorial dimension seriously as a form of rationality. People do not simply go mad when they believe mad things. They rather believe mad things because they want to understand what appears to them to be an (increasingly) mad and incomprehensible world. There is a kernel of reason at the origin of conspiracy theories. However, Jameson also showed that one must locate the origin of such theories within a historical-social transformation, since they emerge at times of “widespread paralysis of the collective or social imaginary.”4 When imagining that the order of the world has become impossible, one can see in conspiracy theories the rationality of a symptom of a certain historical conjuncture. Rationality itself thus has to be rethought historically, and we encounter here what one could call, with a loose reference to Freud, an evenly suspended rationalism. It operates as if inverting Adorno’s claim that “even if it were a fact, it wouldn’t be true,” since for Jameson even if conspiracy theories are entirely made up, there is truth in them.

It can be rational to believe the most nutjob account of how things hang together when there’s otherwise no account of how things hang together. It is a way of insisting that the world needs to be rationally comprehended, especially when it seems to exceed all reasonable understanding. Conspiracy theory is thereby what reason’s demand to totalize itself looks like in times of the crisis of totality—and thereby in times of the crisis of reason. This is why “conspiracy theory … must be seen as a degraded attempt … to think the impossible totality of the contemporary world system.”5 This is why Jameson once called—with a more than fortuitous formulation—the production of “conspiracy plots … the poor person’s cognitive mapping in the postmodern age.”6 It is a vulgar form of reason that emerges when history seems to have gone irrational. This is a rationalism for a state (of history and culture) of the absence of any identifiable raison d’état. Note the demanding nature of this position: to see in all the weird beliefs that we are confronted with today—from those concerning Haitian pet eaters to climate controllers to countless others—nevertheless a form of reason and not simply deem them outside of what can be rationally understood. To be clear: this is obviously no justification, as such conspiracy theories are wrong. But to take their concealed reason seriously means to expand the scope of rationalism. Rationalism here becomes able to account for deviations from rationality in a rational manner. No doubt, this is one of the things that attracted Jameson to psychoanalysis and Marxism. However, for him it is precisely an analysis of products of contemporary culture—Hollywood in particular—that can make exactly this “expanded” rationality palpable. Richard Donner’s 1997 Conspiracy Theory is a good example. In it the main character (Jerry Fletcher, played by Mel Gibson), who has wrong theories about all kinds of things, is at one point—accidentally—right about an enormous conspiracy, which involves the government. Fletcher proclaims that “a good conspiracy theory is unprovable,” for “if you can prove it, it means they screwed up somewhere along the way.” This points to the twisted and inverted dialectics of today’s conspirationality: as if one were to say it must be true because it is not. To Jamesonize means to broaden the concept of, and to always historicize and to conjuncturalize, reason and its mode of operation.

This leads, secondly, to a rethinking and reconceptualization of the very modality of reason’s operations, that is, of dialectics. Jameson opened his magisterial 2009 Valences of the Dialectic with a long elaboration on the dialecticity of the concept of dialectics itself. Dialectics is a strange form of conceiving of thought, because “in its Hegelian form [it] set out to inscribe time and change in our concepts themselves.”7 If rationalism is Jamesonized, one must also Jamesonize our very understanding of thinking along Hegelian lines. Dialecticity—which is the conceptual enemy of “Aristotle and Kant,” who figure as “the great summas of common-sense thinking and subject-object empiricism”8—is identified as the most uncommon-sense manner of thinking, and of thinking thinking. Thought—because it is dialectical—is un-natural, “provocative and perverse,” for this is what it ultimately means for thinking to conceive of itself historically.9 This also entails that whatever stands in opposition to thought or the dialectic must be conceived in historical terms. Dialectics means not only that thought has a history, but that it’s necessary to historicize the very forms of thought and their genesis, even though they cannot but declare themselves to be absolute. One can here start to distinguish, as Jameson has done, between the dialectic, multiple dialectics, and their relationship—the latter necessitating neither a definite nor an indefinite article for the noun, but an adjectival term: “It’s dialectical.” “To speak of the dialectic with the definite article”—and this is just one aspect of how to think thinking—is to “reinforce the more universalistic claims” of “a single philosophical system” that is applicable to whatever content and object.10 The dialectic is then the one method or system to which there is no exception.

As Hegel once infamously claimed about the dialectical method, it is “unrestrictedly universal …; the absolute infinite force, to which no object presenting itself as something external … could offer resistance.”11 Even resistance to the dialectic must be thought in terms provided by the dialectic. The dialectic is a (total) system. But this poses the risk of the dialectic totalizing itself undialectically, that is, of itself becoming ahistorical. This danger, however, is remedied once the dialectic becomes a dialectic, i.e., once it is accompanied by an indefinite article. Dialectics is then regionalized and allows for local specificities. These local dialectics operate in separate regions and are singularly determined by what they are dialectics of (be it the dialectic of space or time, film, industrial development, gender, race, etc.). “At that point the dialectic … is reduced to a local law of this or that corner of the universe, a set of regularities observable here or there, within a cosmos which may well not be dialectical at all.”12 There can exist many different dialectical frameworks that do not necessitate a claim to any all-encompassing dialectic.

For Jameson, these two aspects—the dialectic as one single system and method and dialectics as an untotalizable plurality—were both present in Hegel’s thought. He saw Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit as being guided by what Adorno called the primacy of the object(s) and thereby by the traversal of different unique logics of singular objects and forms of consciousness. In contradistinction to this multiple-dialectic approach, Jameson identified in Hegel’s later Encyclopaedic system and in his Science of Logic—for the purpose of the present article I will ignore the differences between the two13—Hegel’s own reifying production of “something we may call Hegelianism, in contrast to that rich practice of dialectical thinking we find in the first great 1807 masterpiece.”14 One can thus learn from the very philosophical oeuvre which produced the modern dialectic as system and method that even the dialectic can be reified—but also that it can be de-reified if regionalized and read from the genealogical perspective of its origin. This de-reification is what Jameson famously referred to as “theory.” For theory “is to be grasped as the perpetual and impossible attempt to dereify the language of thought”—another impossible task!—and is thus what was supposed to dialecticize the dialectical method and system from within.15 One could see therein a true “unity of theory and practice”—in the practice of theory or in the thinking of thinking, against its reified forms.16 In concrete historical conjunctures this comes with a political charge. Jameson critically identified predominant normative, transcendentalizing, and therefore Kantianizing readings of Hegel as being pacifyingly “Habermasian.”17 Nothing is immune to reification, not even the critique of reification, and therefore not even those thinkers, like Hegel, whose “own analysis would seem to show that the dialectic is out to destroy the concept of law rather than to offer the chance of formulating new ones.”18

Thought must give up its claim to unchangeable lawfulness and allow for the radical discontinuity that is the properly historical to lead the way. Thought must confront what it does not know how to think in advance—history—and this is what dialectics is all about: thinking with and through “the dilemma of incommensurability, in whatever form.”19 For it is precisely in those moments when thought is confronted with a contradictory situation that it must do what it does not know how to do; in these moments one can encounter “those mental events that take place, when someone says, rebuking your perplexity before a particular perverse interpretation or turn of events: ‘It’s dialectical!”20 Dialectics is here the name not for a stable method, but for the invention of “a startling new perspective” where thinking itself becomes surprising, even to itself.21 Jameson’s project was in this very sense—therein displaying a certain solidarity not only with Lukács but also with Adorno22—a manifestation of critical theory. But he also—and therein lies his solidarity with thinkers like Slavoj Žižek and Mladen Dolar—demonstrated that the demand of contemporary thought was to reinvent or reconceive even the dialectic, and thus the very forms of thought. To historicize does not (only) mean to be(come) a genealogist. It rather means to not accept any forms of thought—even any form of dialectics—as a neutral and ahistorical given. This was itself a form of historical experience, since it was exactly with structuralism that, according to Jameson, “dialectical thought was able to reinvent itself in our time.”23 To Jamesonize is thus to periodize all forms, even (of) dialectical thought. Thought is not simply historical, but history can happen to thought in surprising ways—that is, dialectically. To affirm that there are dialectical events in and for thought is to reinvent what thought and dialectics is for times in which it seems impossible to continue to go on thinking.

Dialectics Jamesonized, then, is a conception of the forms of thought that we account for when we think of thinking by means of thought’s own historicity, which leads us thus to think of what is constitutive of thought, which exceeds all lawful account. Thought can emerge from an exception. There is thus “a dialectic … between the non-dialectizable and the dialectizable” at the very heart of thought, which means that here what is totalized—this being the core demand of reason—is an inherent untotalizability.24 Thought is constitutively “not-all” that there is (to use the Lacanian term). In a way similar to Rimbaud’s famous plea that love must be reinvented, to Jamesonize means to be attentive to the potentials and conjunctures that allow for thought to be—totally—reinvented. This reinvention comes with the surprise that (some) things are dialectical—even if this means reinventing what we mean by dialectics and by surprise. For it is precisely these perplexing insights that allow us “to defamiliarize our ordinary habits of mind and to make us suddenly conscious not only of our own non-dialectical obtuseness but also of the strangeness of reality as such.”25 To see this strangeness is to Jamesonize (thought); it means to be on the lookout for what is strange, to break habits of thought, and to follow what cannot but seem off-piste.

Jameson’s rationalist dialectics shows its political, historical, and cultural efficacy, and material embeddedness, when it is linked to the concept of orientation, or cognitive mapping. In a famous text from 1988, Jameson diagnosed a far-reaching orientational crisis that was brought about by our contemporary (non-)world.26 Today, most people experience perplexity and helplessness with regard to the organization of the world. Where do, for example, the components that make up the laptop I buy at an online retailer come from? What are the exact supply chains for the restaurant I enjoy dining at? There is a form of disorientation built into today’s form of capitalism. While in earlier periods “the immediate and limited experience of individuals is still able to encompass and coincide with the true economic and social form that governs that experience,” under late capitalist conditions there is a gap between the two.27

Nowadays individual experience is unable to encompass the economic and social structures that have formed it. In such a historical conjuncture, “the truth of … experience no longer coincides with the place in which it takes place.”28 This diagnosis is partially resonant with what Walter Benjamin called the “poverty of experience,” wherein experience is unable to integrate within itself the conditions under which it takes place. Thus the specific problem that late capitalist development confronts us with is representability.29 Experience becomes disoriented. As long as I can locate myself, for example, in a city where I know more or less how things work and how different places relate, I am able to cognitively situate myself. But late capitalism confronts us with a situation in which “that map of the social and global totality we all carry around in our heads in variously garbled forms” becomes impossible to attain or maintain.30 Jameson’s diagnosis was thus that ours was a situation of disorientation, which a misguided rationalism seeks to compensate for through conspiratorial reasoning.

In response to this one must therefore reinvent “an aesthetic of cognitive mapping,” which names “a pedagogical political culture which seeks to endow the individual subject with some new heightened sense of its place in the global system,” even though it “will necessarily have to respect this now enormously complex representational dialectic and invent radically new forms in order to do it justice.”31 At least from a certain moment of its development, capitalism deals in and reproduces itself by means of disorientation.32 It deskills all of us with regard to our cognitive mapping abilities. It then becomes the task of theory—and of a reinvented dialectical rationalism—to (attempt to) orient us. In order to do this, dialectical rationalism must remain faithful to what cannot but appear lost, namely the “more modernist strategy, which retains an impossible concept of totality whose representational failure seemed for the moment as useful and productive as its (inconceivable) success.”33 Insisting on the possibility of a cognitive map in times of its impossibility—in times in which the very idea of a map of global capitalism has been invalidated by the tectonic shifts in its political economy—meant for Jameson to defend the idea that despite its apparent complexity and seeming irrepresentability a new orientation can be achieved. It meant, together with Hegel, emphasizing the surprising powers of thought to totalize.

This (im)possible orientation stands in line with the rational demand to comprehend the apparently incomprehensible irrational non-world of capitalism, and draws from the inventiveness of—critical—thought. It is linked to the claim that there is an operator of totalization, i.e., that we can totalize the present historical situation. How? By presupposing “a certain unifying and totalizing force,” which is “simply capital itself,” for “it is at least certain that the notion of capital stands or falls with the notion of some unified logic of this social system itself.”34 To remain a rationalist dialectician in times of disorientation and the absence of (individual and collective) cognitive mapping means to learn again how to totalize. It means to affirm the absolute powers of rational thought to reinvent itself in a period that appears to be that of its defeat, and thereby to also concretely determine—in line with Marx—that there is a logic to that which cannot but appear to be erratic and obscure: namely, capital(ism). This allows us to locate ourselves in what we totalize and to thereby affirm that we can think “it” in its totality, from our side. This is a way of seeing reason where there seems to be none and of inventing new and surprising forms of orientation. That this orientation needs to be mediated with individual experience implies that one also has to conceive of an aesthetic adequate to it. But to think present-day capitalism in its totality—and thereby also its difference from its previous forms—cannot but mean: to also think it to the end, and thus to think the end of it. However difficult or even impossible this may be, Fredric Jameson worked tirelessly throughout his lifetime to render such an imagination possible, and to make apparent that this is what thought can do when it follows the demand of reason. Therefore—as long as it takes to get there and even thereafter—always Jamesonize!

G. W. F. Hegel, The Difference Between Fichte’s and Schelling’s System of Philosophy (SUNY Press, 1988).

Fredric Jameson, “The Three Names of the Dialectic,” in Valences of the Dialectic (Verso, 2009), 15.

Fredric Jameson, Brecht and Method (Verso, 1998).

Fredric Jameson, “Totality as Conspiracy,” in The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space in the World System (Indiana University Press, 1992), 9.

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, Or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Duke University Press, 1991), 37.

Fredric Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, ed. C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (University of Illinois Press, 1988), 356.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 3.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 4.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 4.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 5.

G. W. F. Hegel, Science of Logic (Cambridge University Press, 2015), 826.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 16.

For this, see Rebecca Comay and Frank Ruda, The Dash—The Other Side of Absolute Knowing (MIT Press, 2018).

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 8.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 9.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 55.

Fredric Jameson, The Hegel Variations: On the Phenomenology of Spirit (Verso, 2010), 54.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 14.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 24.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 50.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 50.

See Fredric Jameson, Late Marxism: Adorno, or the Persistence of the Dialectic (Verso, 2007).

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 17.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 26.

Jameson, “Three Names of the Dialectic,” 50.

This concept also plays a crucial role in Jameson, Postmodernism, 51ff.

Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” 350.

Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” 351.

For this see also Fredric Jameson, Representing Capital: A Reading of Volume One (Verso, 2014).

Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” 353. Jameson’s concept of cognitive mapping is inspired by Kevin Lynch. See, for example, Lynch, The Image of the City (MIT Press, 1960).

Jameson, Postmodernism, 53.

This is a diagnosis that can also be found in Alain Badiou, Remarques sur la disorientation du monde (Gallimard, 2022).

Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” 408.

Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping,” 409.