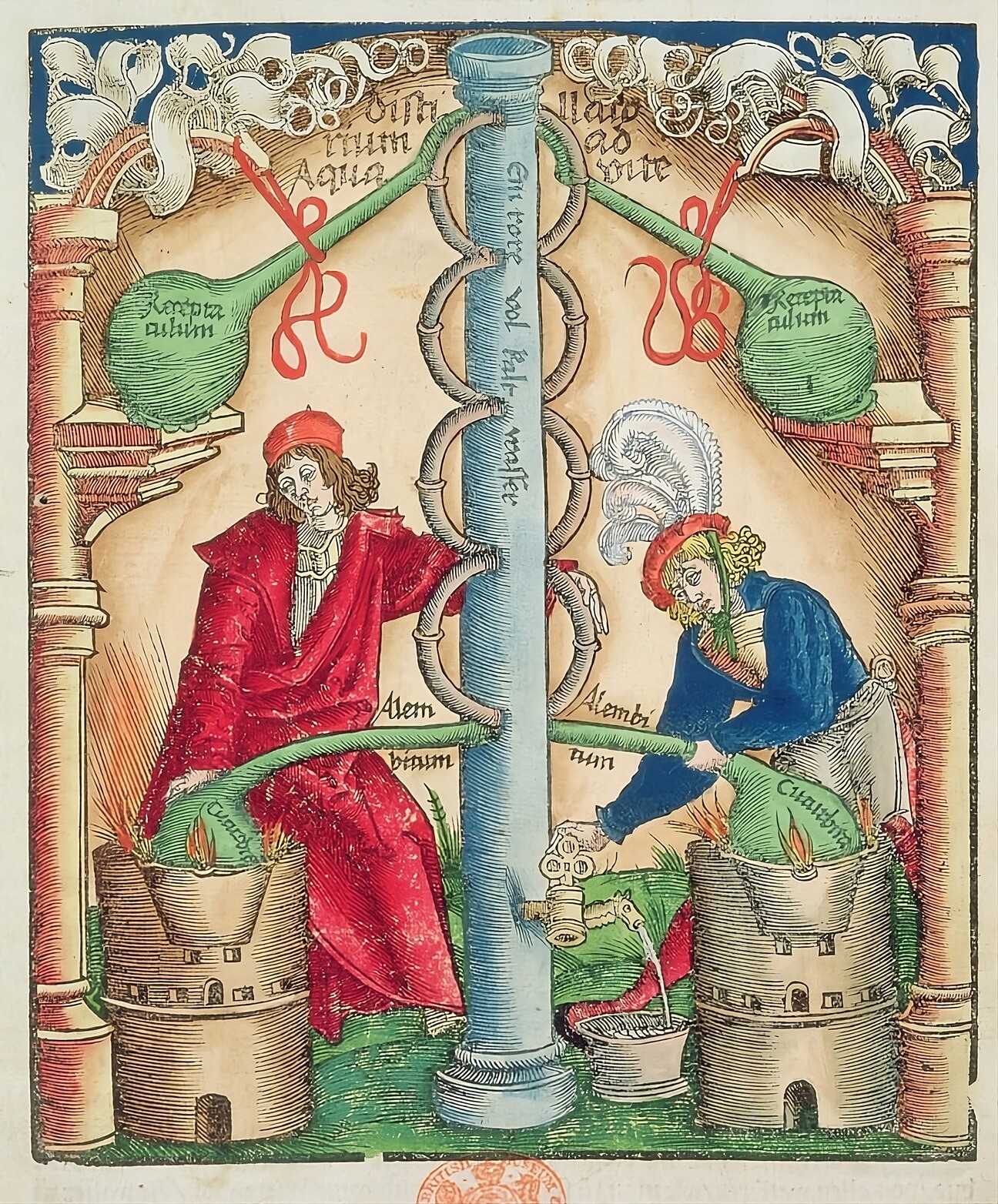

Hieronymus Brunschwig. The Distillation of “Aqua Vitae” (1512).

In her White Quartz Room, she ate ipadu, smoked tobacco and started thinking about what the world should be like.

- Umusi Parakumu, Before the World Didn’t Exist.

In the introduction of the English translation of the fourteenth-century classical Persian poem Gulshan-i Raz (The Garden of Mystery), scholar and translator Robert Darr uses the notion of projection as an essential metaphor to comprehend the philosophy that fuels the poem’s verses.1 Following the thought of Ibn Arabi and the school of Illuminationism that influenced the writing of the poem, Darr describes God as the light of a projector filling the surface of a blank screen of nothingness. The world, cosmos, humans, and other beings that compose it would be the images projected into this emptiness. Although created by light, they simultaneously are and are not of the same essence as the projector’s light. Darr explains:

What is seen is actually God’s light shining through the film of every individual essential archetype and projected onto the screen of relative existence.2

The key in Darr’s metaphor of projection is this liminal state of relative existence, this projected surface on which more than an encounter takes place. There is a participation between the divine light, the screen, and the human world of the film that interpenetrates both opposite poles of being and nothingness. Projection thus becomes the possibility of existence in this environment at the unstable partition of space and time, matter and fiction, its intersection and mutual discovery. If the Sufi poems of the fourteenth century may seem ungraspable in their mystic candor, one doesn’t need to go this far to find this frontier traced amid light, bodies, and surfaces. After all, this is what has defined cinema as an art form for more than a century, from endless pantomimes of destruction, profane illuminations, and phantom spectacles to narrative identification, countless industrial crafted plots and subplots, the white cubes of art galleries, and the infinite poor darkness of sumptuous multiplexes. Light, screen, bodies; inside, outside, and in-between. Projection as destiny. Carved in the pupils of the ticket woman (Chen Shiang-chyi); enveloped by the drips of glows and ghosts in the last screening of a movie theater in Tsai Ming Liang’s 2003 Goodbye, Dragon Inn; reaching back to Buster Keaton playing the bewitched projectionist who mimics the actors’ movement and their phantasies at the small projection booth in the last scene of Sherlock Jr. (1924). Keaton, in this famous scene—his hesitation and fragile gestures of emulation as framed by the window that connects the projector to the screen—confesses all the unfathomable secrets hidden in light’s imperturbable way of faded worlds and their crossings, the delimitations of an entrance and an exit in and out of an atmosphere opened by projection.

It is at the edge of this destiny and its flickering, from the folds and curves of linear perspective’s limits that entangle the projector and the screen, material and immaterial, all the particles of light and shadows lost amid centuries, that Giuliana Bruno writes her Atmospheres of Projection, searching to think cinema first and foremost as an environment of transmutation. Within this open genealogy, projection is not the starting point but the most radical step of a trajectory that begins with the anatomy of technological images’ affection. In her previous book Atlas of Emotion, which outlines cinema’s capacity of making a “world of affects visible,” Bruno contrasts the myth of the optic-centric art form with an archeology of the tactile and spatial dimension of the moving image 3. In a constellation that ranges from cartography and travel to the architecture of film theaters and mechanic dolls, Bruno starts “looking elsewhere for the founding myth of cinema,” which “means looking differently: ‘spacing’ a different spectatorial model, opening other paths of research, and highlighting different aspects of the language of cinema.4 In her words this “traveling back through the origins of film” is capable of designing “a different imaginary scene—a site in which spectatorial voyages take place, a ‘set’ of multiple inhabitations.”5

Thinking in terms of multiple inhabitations is to think in terms of the manner that the image envelops and delimits an environment. In their enviromentality, images and media deny the disembodiment of omnipresent viewers, which were crafted since Hugo Münstersberg on the basis of moving images representing “the free play of our mental experiences and which reach complete isolation from the practical world through the perfect unity of plot and pictorial appearance.”6. Bruno’s work constitutes a radical shift away from the mimetic window, from Metz’s idea that “film is like a mirror”7, where cinema is condemned to the abstractions of thought and consciousness, the self-reflexivity of the eye, and all the cynic demons from storytelling to propaganda in the obsessive thematization of its own death and lost innocence. Bruno abandons both the death of cinema mourning and this clausthrophobic notion of visual media to theorize the haptic architecture of relations and affection that take the eyes as a touch in a surface. The moving image becomes a door of reciprocity because, as Merleau-Ponty once famously wrote, “who sees cannot possess the visible unless he is possessed by it.”8

To be possessed demands one to be enclosed, to be surrounded, to share an environment whose very etymology comes from this being encircled. Bruno has been thinking and systematizing the technical image as an environment of participation, an envisioned surface and a fabric of affects that has reality and materiality in its textures and ornaments but is without the phenomenological dream of reconciliation with the flesh of things. What is at stake here is not so much the dreamed primeval matrix of interdependency that Merleau-Ponty talks about and sees in the cosmogony of Cézanne’s inks, but the transductions and transmutations acquiring form in the motion and emotion always concealed within electronic surfaces More than movement or time, the technical image as projective screen becomes to Bruno “an architecture of passage, openness, and transformation that, in turn, creates a transitive, relational environment and sites of transduction.” 9

In her earlier work Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media, Bruno argues from the start that “materiality is not a question of materials but rather concerns the substance of material relations,”10 allowing for the crucial leap where this surface of the technical image in itself can, through projection, “makes us aware of the material existence of the screen: it draws our attention to the reflective electrical surface that film requires to exist as a display of externality.”11. Film becomes embodied in this porous environmental body of projection, this externality that, as an envisioned surface, shares itself becoming screen. In projection, both subject and object, viewer and artwork, participate in each other’s invention, in this becoming screen: “the art of projection can still not only produce affect but effect change, and this includes the transformation of forms and mediums in the arts.” 12

Linear contemplation is woven and folded in projection, understood as a radical cultural technique of the border, of opening atmospheres. The Platonic cave, the primeval scene of cinema as captivity, where the solid logocentric and phallic truth of light cannot be shared, collapses in the metamorphic architecture of a shared enviroment. Bruno has found in projection a manner of conceiving of and observing images, attuning both to their interior and exterior, to their matter and to their fiction. Like a map of a dreamed city, these images acquire reality at every new trace. This is what, since Atlas of Emotion, she has been looking for elsewhere. Atmospheres of Projection begins with the myth of Dibutades. It is the book in a nutshell:

A Corinthian maid, Dibutades, is in love with a young man but learns he is to leave the country. In the face of this departure, she devises a way to envision, or rather envisage, his image, and in this way to keep him with her ‘virtually.’ Using lamplight, she casts a shadow of his figure onto the wall and traces its outline.13

The story, as Bruno acknowledges, is more famous for its second part, where Dibutades’s father, Butades, transforms the projection into a sculpture in relief and allows it to last. But this distracts from the essential fact that the sculpture can only exist through the projection cast in the wall. It is the trace of the projection that allows for this sculpture to emerge, a sculpture that, as a result of the projection, is not an imitation but the materialization of an atmosphere of invention that conciliates the preservation of the past lover and the becoming of his return. It is not a painting, but a moving image in this multiplicity of times and places that it transports us to. Its power resists in how it draws one to the wall, to its matter, where it has been fixed, and simultaneously expands it by the activity and activation of both viewer and creator in what Bruno calls a shared “zone of activity” that “shapes the ecology of art, for aesthetics is not an isolated affair but participates in interrelated milieus of transmission, relation, and exchange. This sense of ecology especially pervades the kind of art concerned with this particular environment: the atmosphere of projection.”14

While the trace lasts on the wall, while it remains projected on the wall, everything is possible in this nascent interrelationality. Everything is in motion, like a forming cloud. Floating to be deciphered. From Dibutades’s casting on the first page of the book to the nebular projections and atmospheres in Ho Tzu Nyen’s The Cloud of Unknowing created for the 2011 Venice Biennale, which illustrates the book’s final pages, presence and absence, waiting and hope, fleeting climates of drought and storm: all are equally of relative existence. Bruno offers tremendous plasticity in this sharing of a radical possibility of coexistence that is the essence of her atmospheric thinking. This is all to say that the book’s proposed atmosphere could have started elsewhere, in a different projective image, in Nyen’s nebular projections, but also on any of the artists that vigorously illustrate its previous chapters, ranging from Germaine Dulac to Hito Steyerl. The scene of Dibutades, a scene that Bruno remarks is not “of captivity but of captivation,”15 captivates precisely through an allurement of one’s imagination and its capacity to participate in the space in between trace and sculpture, potential and actuality .

This space of projection, which Bruno architects from so many different theories, artworks, and disciplines, follows Walter Benjamin’s recipe in the final excerpt of One-Way-Street, “To the Planetarium,” in which one ‘conquers the frenzy of destruction only in the ecstasy of procreation.”16 Projection becomes a site for the procreation of all the possible crossroads within the moving image as it fits simultaneously the Desana cosmology in which the primordial goddess, the so-called ‘grandmother of Earth,” creates reality in a room of white quartz through the smoke of her tobacco, all the way to a cinema not yet born but pregnant in and of atmospheric environments sculpted by projection’s past light and future smoke.

The future is always in sight in the book and its scope. Although Bruno dialogues with foundational myths of the moving image, its invention, early experimentations, and forgotten pathways, projection continues to be intimately related to the question of the future’s project and planning. Marx asserted influentially that planning production and labor was the key to leaving the anarchy of the market’s “invisible hand” and the idealistic spirit of philosophy to reach freedom. He states in Das Kapital that “the life process of society, which is based on the process of material production, does not strip off its mystical veil until it is treated as production by freely associated men, and is consciously regulated by them in accordance with a settled plan.”17 His message is clear: emancipation demands a project, and therefore, projection acquires a relationship not only with the future per say but with the possibility of the production of emancipation and appropriation through the envisionment of the future—like the many installations and architectonic spaces that Bruno thematizes, it touches the space of the freedom through a form of forecasting.

Nonetheless, projection as a concept has another consecrated use that Bruno faces, described by Freud in the context of a case of paranoia. To him, projection happens when “an internal perception is suppressed, and, instead, its content, after undergoing a certain kind of distortion, enters consciousness in the form of an external perception. In delusions of persecution, the distortion consists in a transformation of affect; what should have been felt internally as love is perceived externally as hate.” 18 The history of projection in the context of psychoanalysis is so broad and intricate that it could not be summarized merely by Freud; nonetheless, projection still possesses in psychoanalysis the dimension of a subconscious toll of defense, wherein the internal is necessarily distorted and displaced to the external. Here projection is not a meticulously crafted and conscious plan, but a spontaneous and uncontrollable force of defense paralleling the uncontainable forces in the elements and nature of an environment. It is the energies in every light and surface, the tempest dormant in clouds, but also the body of the viewer within the space.

Balancing herself between the project and spontaneity, design and accident, line and curve, Bruno brings up the projection’s alchemical root from the start. Indeed, as she points out, projection appears as the sign of the transmutation and movement of matter in the context of the Magnum Opus, the crafting of the philosopher stone of alchemy through its many phases and the process of mixture and purification. This alchemical genealogy of projection highlights what Bruno sees in the work of Diana Thater, “who transforms material space through light forms, which are themselves, in turn, materially changed in the process.”19 In this manner, project and spontaneity interpenetrate each other to further elaborate the thought of the atmosphere in which what is solid dissolves in the rarefied air of an ecology of interrelations, into the pure “environmentality” of the image.

In this atmosphere of interpenetration, the thought of projection finds its most urgent reverberations, namely that of publicness and its very essential “environmentality.” After all, as air and wind that envelops, moves, and transmutes, projection is symbiotic to images’ collective and spatial dimension; in its atmosphere and interplay of distortions of internal and external in and out of themselves, projection necessarily acquires and orients to the very environment it forms and transforms. Cinematic time, before a crypt of the afterlife, becomes a time of partaking and, in doing so, comes back to Erwin Panofsky’s recipe of the “new technological, artistic medium as dynamization of space and spatialization of time.”20 It gives time to an exhausted age through this form of environmental participation and creative existence in the population of images and their networks which our time and life became part of.

Robert Smithson, whom Giuliana Bruno refers to many times in her works, states in his essay “A Cinematic Atopia” that “ultimate movie-viewing should not be encouraged, any more than ultimate movie-making.”21 In the same text, he proposes building a cinema in a cave and recording the manufacturing and construction of this film theater cave; the film would be the only movie ever shown there. Smithson’s proposition is a late attempt to reconcile in cinema the modern split that the art form is born from. After all, in the famous and inescapable “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility”, Benjamin describes how cinema is necessarily related to the imposition of exhibition value over cult value in an artwork. Reproducible images, undressed of their presence, of their here and now, fill the world as networks of absence and specters spreading rapidly in the regime of mass consumption. Benjamin’s text, torn between the mourning of aura and the possibilities of exhibition value to actualize “the political man” within reproducible images, is split between the fascist threat of the aestheticization of politics and the communist response of politicizing art. Almost one century after Benjamin’s text, exhibition value remains in permanent crisis, oscillating between total alienation and insufficient mobilization. Still, it doesn’t change the fact that, as Günther Anders once posed, “since the world comes to us only as an image, it is half-present and half-absent, in other words, phantom-like; and we too are like phantoms.”22 Smithson’s proposal of conciliating the building of the cave with its exhibition is a reaction to this half-state between captivity and capitulation. The matter here is not that of spectacle, passivity, or vita-contemplativa versus vita-activa, but is of a more delicate kind. If contemporaneity is more and more based on activity, on interchange and the circulation of people and images, to the extent that some speak of immediacy as a style of a too-late capitalism phagocytosed by technical images23, no matter how much these images absorb and engulf life with their production and consumption, they remain incapable of replacing a relationship like that which Benjamin describes in the ever-close distance of ritual and magic relation proper to cult value.

It would be an easy temptation than to tie Bruno’s paradigm shift in the technical image to the precepts of relational aesthetics. Famously conceived by Nicolas Bourriaud, relational aesthetics claims not to “prepare and announce a future world”24 but to instead “modeling possible universes” in relationality.25 But although Bourriaud’s conception of art as “a state of encounter”26 shares an affinity with the sympathetic surfaces of affects, projection, and its atmospheres of relationality, he can only think of relationship as a scene of responsibility. Referencing Serge Daney’s use of Levinas, Bourriaud’s conceptualization remains intertwined with the motif of the face, its ethic, and the time of responsibility towards the other. In this time, the too-close distance of cult value is reconstructed in the artificial tabernacles of art’s negativity. When Bruno defines projection in close kinship with the concept of tuning or Stimmung, she goes further because in it, “boundaries between bodies, and distinctions between bodies and matters, human and nonhuman, can be not only negotiated but crossed.”27 Projection in its atmosphere then becomes a cultural technique for crossing; it radicalizes relation into an interwining, it privileges collective invention like that between an orchestra and its sheet, the dancer and the rhythm—movie viewing meets movie making as they were never thought separated. What Bruno’s pivotal historiography and discussion of Stimmung (often translated as mood, tuning, or attunement and crucial to both art and philosophy), from Georg Simmel and Leo Spitzer to the beginning of film theory with Béla Balázs, allows one to perceive is that this reciprocity between viewing and making was there from the start. It is the very bond between projection and atmosphere. If she stresses that Stimmung’s “idea of rhythm and resonance is significant to this study, especially for the way it suggests a tone, tonality, disposition, reverberation, or transposition in an ambiance,” it is because the atmosphere opened by projection is constantly tuning and being attuned to the environment, to the viewer and its inhabitant. 28 It is always actualized in shared participation of a weather experienced and forecasted. Since the start, moving images have had the capacity to enlarge the material world, to share life and sympathetic force with it, because they dwell in a particular melody that transforms reality while also being transformed by it. Always reciprocally discovered and augmented by the senses and the environment, the technical image is a “resonating environment that resonates within”, expanding both its otherworldliness and its radical immanence. 29

Atmospheres of Projection is thus a rare book. It is not only a timely contribution to the study of moving images of our age but is also a work that can be said to invent what has always been there, what has been overlooked like a constellation obstructed by poor air. Through Bruno’s research, we come to see glowing, cleanly now, all these traces connecting so many different stars, from Pepper’s ghost shows to contemporary art, with the impression that this has always been the case. The genealogy it outlines reflects what Henri Bergson wrote once in relationship to the artistic act:

As reality is created as something unpredictable and new, its image is reflected behind it into the indefinite past; thus it finds that it has from all time been possible, but it is at this precise moment that it begins to have always been possible, and that is why I said that its possibility, which does not precede its reality, will have precede it once the reality has appeared.”30

In this sense, in the book’s cover, with Varda’s Bord de Mer, shinning livid ocean projected in a wall, the screen dripping onto the floor and the sky’s rarefied air above, already resides some of the elemental life, first glimpses of light, of many moving images past and to come. Not anymore constrained to movement or time but attuned to a shared environmentality and a path of discovery. Their remembrance and evanescence are the open paths of theory and art, where one can find again the same truth of fourteenth-century Persian poetry, which tells us in its projective imagination and condensing atmosphere: “If you pierce the heart of a single drop of water, from it will flow a hundred clear oceans.” 31

This text is aimed as an analysis and exploration of Giuliana Bruno’s 2022 Atmospheres of Projection: Environmentality in Art and Screen Media and the paths it outlines for film and media theory.

Robert Darr in Maḥmūd ibn ʻAbd al-Karīm Shabistarī, Garden of mystery: The gulshan -I rāz of Mahmud Shabistari (London: Archetype, 2007), 16.

Giuliana Bruno, Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film (New York: Verso, 2002), 2.

Bruno, Atlas of Emotion, 138.

Bruno,. Atlas of Emotion, 138

Hugo Münsterberg, Hugo Münsterberg on Film: The Photoplay: A Psychological Study and Other Writings, ed. Allan Langdale (London: Routledge, 2002), 138

Christian Metz, The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2000),45

Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Claude Lefort, The Visible and the Invisible: Followed by Working Notes (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 2000), 134.

Giuliana Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection: Environmentality in Art and Screen Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022.), 122–23.

Giuliana Bruno, Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media (Chicago:University of Chicago Press, 2016.) , 2.

Giuliana Bruno, Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media (Chicago:University of Chicago Press, 2016.), 59

Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection, 14.

Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection, 1.

Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection, 11.

Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection, 7.

Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings, trans. J. A. Underwood (New York: Penguin, 2009), 112.

Karl Marx, Capital, (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1974) 52.

Sigmund Freud The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud Volume XII 1911-1913 (London: The Hogart Press, 1958), 66

Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection, 164.

Erwin Panofsky quoted by Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Univ. Press, 1995), 30.

Robert Smithson, “A Cinematic Atopia,” Artforum, September 1971, 53–55. →

Anders, Gunther Anders,. “The World as Phantom and as Matrix,” Dissent Magazine, January 24.. 2023. →

Anna Kornbluh, Immediacy, or the Style of Too-Late Capitalism (New York, Verso, 2024)

Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Paris: Les Presses Du Réel, 2002),13.

Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, 13.

Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, 18.

Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection, 50.

Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection, 90.

Bruno, Atmospheres of Projection, 95.

Henri Bergson, “The Possible and the Real, Bergsonian.org, July 10, 2019, →.

Maḥmūd ibn ʻAbd al-Karīm Shabistarī, Garden of mystery: The gulshan -I rāz of Mahmud Shabistari (London: Archetype, 2007), 48.