From Benjamin Ives Gilman, “Museum Fatigue,” Scientific Monthly, January 1916.

Museums invest millions of dollars in impressively designed exhibition spaces concerned with beauty and aesthetics. These spaces are often bright, large, and highly air-conditioned, presenting wonders for hushed, focused contemplation. To whom these wonders are presented, to which bodies, seems to matter little.1 It could be any set of eyes consuming, any set of feet shuffling through. The art on view might be cutting edge, provocative, or progressive. It might interrogate cultural hegemony through art or curation or both. And yet the treatment of the embodied visitor, when considered at all, is often trapped in the same paradigm as the very earliest art museums—look, read, absorb, exhaust, go home.

Museums and art exhibitions have evolved through several models to get here: the imposing power of church and princely collections, the moralistic educational missions of early public museums, the bright and spectacular museums of the last century.2 Across these varied museum iterations, viewers have been consistently treated as abstract types—subjects, souls, citizens, consumers—or isolated and privileged body parts—minds, eyes, and feet that process works of art and move from place to place in the museum space. (Tony Bennett calls modern museum visitors “minds on legs.”)3 The resulting “museum fatigue” is attributed to the inconvenience of the human body, which drags one down and becomes an obstacle to enlightenment and learning. A source of constant need—rest, water, food, bathrooms, directions.4

The legacy of this treatment of museum-going bodies can be seen in comments, familiar to any museum worker, about visitor exhaustion: there aren’t enough benches, there’s too much text, I don’t know how to get where I need to be, I can’t find the bathroom. In 2017 these ubiquitous comments culminated in an eye-opening finding reported by Culture Track: a significant number of people never go to museums, with many saying “they are not for people like me.” In addition, people with disabilities are 59 percent more likely to avoid cultural activities because they’ve had a poor experience.5

It is time for museums to imagine a new spatial typology that sees the bodies of their visitors as equal participants in the experience of art and culture—that allows for embodied selves as whole, rich, and worthy.6 Artists have taken up the cause themselves in recent years. In their series Do You Want Us Here Or Not (2017–20), Shannon Finnegan prints text on benches: “This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long. Sit if you agree”; “Museum visits are hard on my body. Sit if you agree.”7 Carolyn Lazard’s series Institutional Seat 1–4 (2022/2024) at the Walker Art Center is provocative simply because it endeavors to be as comfortable as possible. Though both artists approach the topic through seating, their work provokes a broader question: What would it look like if museums cared for people with the same level of rigor that they care for collections, investing in spaces that truly and warmly host people and artworks equally? This idea is not just about access or broadening the types of visitors who come through the door (although these are both critical). It is about a fundamental shift in the way museums are spatialized, in how they apportion and design space for art and for people.8

To work towards this paradigm shift, institutions must understand and acknowledge their histories in order to uncover what is standing in the way of true models of care. Investment will be required. This could be as simple as thoughtfully designed visitor furniture to support rest and contemplation. It could be as holistic as a strategy that considers experience design, art display, information sharing, and spaces to meet basic human needs like food, water, a place to nurse a baby, take medication, rest, or use an accessible bathroom. We are all living with our human bodies and we all deserve to experience the riches of our culture—why can’t we have both?

An exception to this is museums’ analysis and reporting of visitor demographics. Such statistics help institutions appeal to historically under-targeted communities, but I argue that this approach reduces human bodies and their needs to numbers rather than truly engaging in holistic care for them.

Krzysztof Pomian, Collectors and Curiosities: Paris and Venice, 1500–1800, trans. Elizabeth Wiles-Portier (Polity Press, 1990); Charlotte Klonk, Spaces of Experience: Art Gallery Interiors from 1800–2000 (Yale University Press, 2009).

Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum (Routledge, 1995).

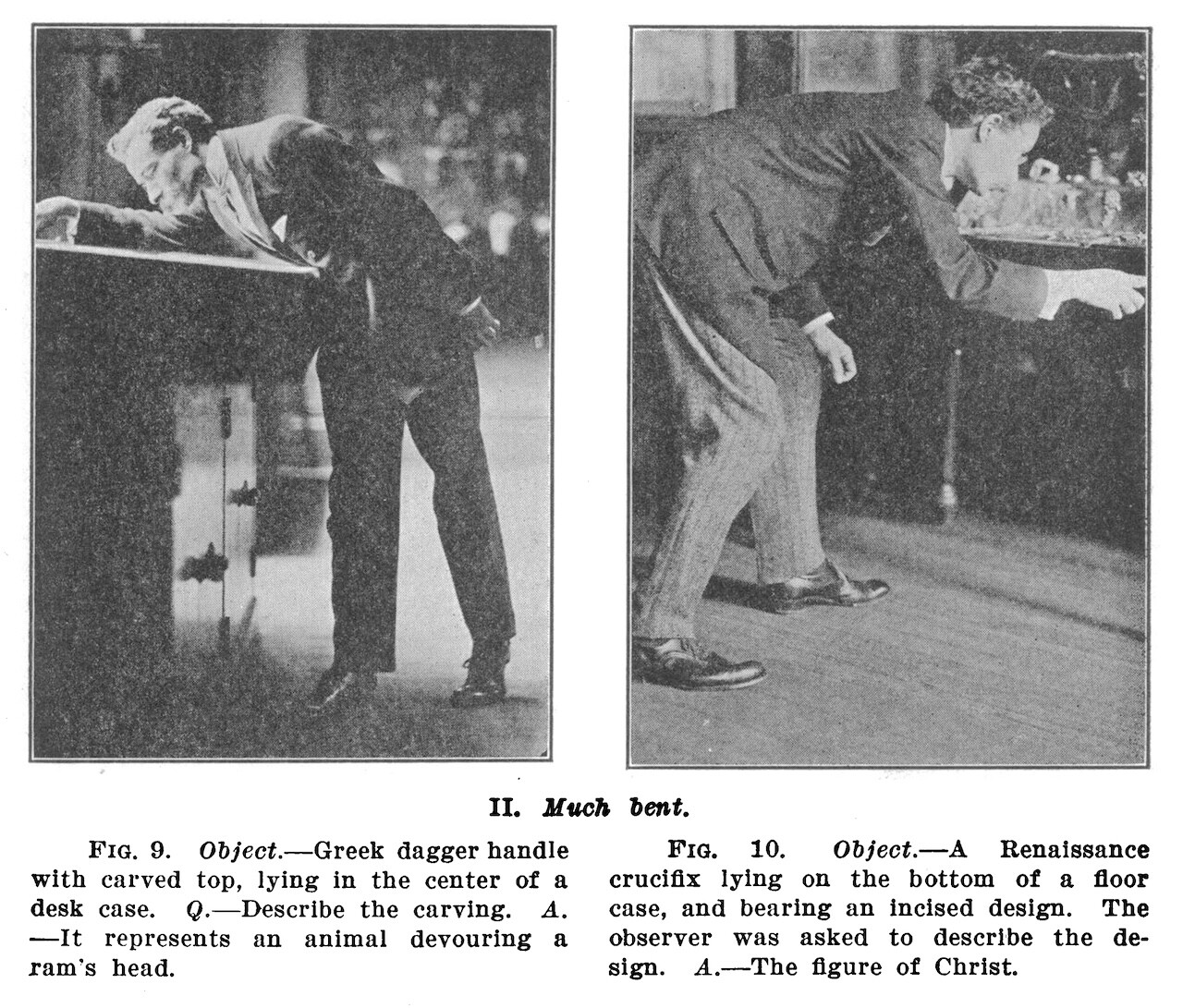

Many articles have been written on the phenomenon of “museum fatigue” and its scientific basis (or lack thereof). The earliest was Benjamin Ives Gilman, “Museum Fatigue,” Scientific Monthly 2, no. 1 (January 1916). A good summary of this literature is provided by Stephen Bitgood, “When Is ‘Museum Fatigue’ Not Fatigue?,” Curator: The Museum Journal (January 2010).

See →.

We can take our lead in this type of thinking from disability scholars: Janice Rieger, Design, Disability and Embodiment: Spatial Justice and Perspectives of Power (Routledge, 2023); Jos Boys, Doing Disability Differently (Routledge, 2014); Brooke Wyatt and Jessica Cooley in conversation, “Both/And: Crip Materiality,” American Folk Art Museum, September 21, 2023; “Making the Inclusive Museum,” symposium, Architectural League NY, January 26, 2024.

A good discussion of Finnegan’s work can be found in Delia Harrington, “Do You Want Us Here or Not: Fighting for Accessibility in Art Spaces,” Art Dusseldorf Magazine →.

For a discussion of disability in architecture that goes beyond access and into fundamental conceptions and constructions of space, see David Gissen, The Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes beyond Access (University of Minnesota Press, 2022).