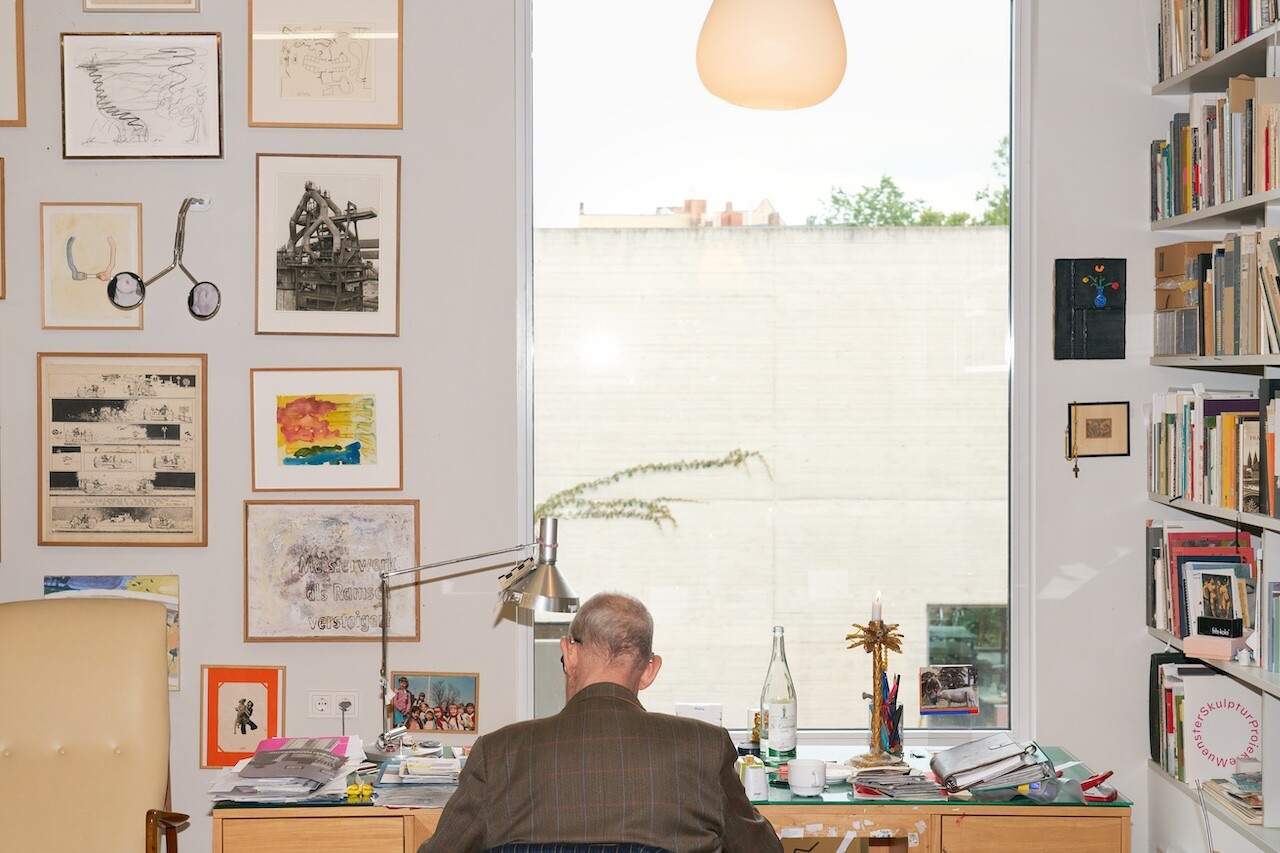

Kasper König. Photo: Daniel Poller (c).

Daniel Birnbaum: You worked with Kasper König when you were very young. What did he teach you?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: I was just about to say: everything. But of course times have changed and things have developed, so that would not be true. But he did teach me the most important thing: to trust the artists.

DB: That’s a good place to start. Kasper was always on the artists’ side. He didn’t try to push his own ideas on them, but followed them in the direction their art took them. Even when he curated large shows, he remained a coconspirator, always a kind of accomplice to the artist.

HUO: Exactly. And it didn’t matter if the artists were young and unexperienced or very famous. When Kasper passed away, a few artists sent me lovely remarks on how it had been to work with him. Both Nicole Eisenmann and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster were invited to present works at the Skulptur Projekte in Münster and valued the collaboration with Kasper immensely.

DB: So what did they emphasize?

HUO: This is what Nicole wrote: “Developing my piece for Münster took five years from beginning to end. Kasper gave all of us artists the time and the careful consideration necessary for the sculptures to be done well. His love of art was demonstrated by a deep thoughtfulness and seriousness … He was a gracious man, deeply creative, mischievously funny and one of the greatest thinkers I have had the honor of knowing.”

DB: I remember Dominique’s beautiful work for Münster in 2007, all those strange objects on the green lawn. What did she have to say?

HUO: She emphasized the fantastic idea of a show that happens every ten year. All those years involving the number seven somehow became Kasper’s time: 1987, 1997, 2007, 2017, and soon 2027. And then she talked about the incredible postcards that all of us have received and she called Kasper the biggest postcard sender in the universe. This is how her statement ended: “My unrealized project for Kasper was always to send him a giant postcard. Larger than a bed. It’s now written with tears and joyful gratitude.”

DB: Perhaps one can sum up Kasper’s approach like this: it is not the job of a curator to impose his or her own signature but rather to be a mediator between artist and public. Making the art visible is what it’s all about.

HUO: Precisely. But that doesn’t mean the curator cannot be inventive when it comes to inventing new formats. We’ll come back to that. Kasper invented many things, not only the wonderful postcards, which are actually small collages. I think one should make a book with them.

DB: I wonder if it was Kasper who gave On Kawara the postcard idea?

HUO: I guess it was a morphogenetic field, as Rupert Sheldrake would say. They were very close friends and started sending postcards across the world at the same time.

DB: Most of Kasper’s friends were artists. And yet, he did become a kind of power player in the art world—despite the fact that for most of his life he was not responsible for any major museum. He never had buying power. Thank god being close to the artists remained more significant to him than any bureaucratic role. How did you actually start working with Kasper?

HUO: It began in a quite odd way. In 1990 I had come to Saarbrücken, in the west of Germany, on an errand for Fischli and Weiss, who were my friends in Zurich. The job was a funny one. I was asked to go to a power plant. Strangely enough, it was host to a project inviting contemporary artists to create installations. Fischli and Weiss created a snowman, which they wanted to install in a glass refrigerator that was powered by excess electricity from the power station. As long as electricity was generated, there would be a friendly snowman on display. And he would not melt.

DB: You brought snow from Switzerland?

HUO: Well, to be precise, it was a snowman dummy, a kind of test figure for the piece. When I arrived, I noticed a man who was waiting for the snowman. It turned out to be the project’s curator, Kasper. That day we had conversations that led to many collaborations and first of all a book. Books played a big role for Kasper, we should talk about that. But what about you—how did you actually start working with him?

DB: It was Gabriel Orozco who brought us together. As you know, I was active as a critic before I started to curate exhibitions. In the mid-1990s I wrote a lot and travelled all the time. But I had never been in Frankfurt, where Kasper lived and worked. Gabriel had been invited to make a show at the Portikus, the kunsthalle that Kasper created when he became the rector of the Städelschule in the late 1980s. Gabriel asked me to contribute an essay for the catalogue and invited me to the opening.

HUO: So your first collaboration was also a book?

DB: Yes, an essay on Gabriel. I knew of the Portikus only from hearsay and from quite impressive publications. Of course, I expected a major institution and was somewhat taken aback when I realized it was simply a container hidden behind a neoclassical facade. I stepped out of the taxi and entered the silent gallery space. There were no viewers around and I was alone with a photographer who documented the show when somehow, from nowhere, Kasper arrived and said, without asking any questions or introducing himself: ”I would like to show you some of our books.”

HUO: Of course Kasper was always close to the world of books with his brother Walther, the amazing publisher. But there are a few more specific things that should be mentioned. The artist book became a key aspect of art in the 1960s, and Kasper recognized this early on when teaching in Halifax in the early 1970s. He edited the Press of the Novia Scotia School of Art and Design and published really beautiful publications with Yvonne Rainer, Dara Birnbaum, Michael Snow, Steve Reich, and many others.

DB: You said that your first collaboration was a book.

HUO: Yes. After that meeting in Saarbrücken he asked me whether I would collaborate with him on an anthology, Der Jahresring, to be called “The Public View.” The idea was to create a sort of yearbook in which various artists and writers would collaborate. It was really a kind of group exhibition using the printed page as a medium. I traveled every week by train from Switzerland to Frankfurt, where he was the head of the Städelschule. I started attending lectures at the school.

DB: You actually lived in his office, right?

HUO: Yes, I spent day and night there. Since I was in my mid twenties at the time, most people probably thought I was one of the students. And in a way I was, because that is where I got to know amazing people like Enric Miralles, Dara Birnbaum, Peter Cook, and Cedric Price. I know that for you it is different, because that same office where I spent so much time later became yours when you took over as rector of the Städelschule after Kasper.

DB: Yes, it all went very quickly. During that first visit at the Portikus in 2000, Kasper told me that Frankfurt is an airport with a city not a city with an airport. I had no idea that I would stay for a decade, but just a few days later a fax arrived inquiring if I would be interested in the position of rector of the Städelschule. I remember it looked a bit strange—“due to severe technical problems,” a handwritten note clarified at the bottom. It was Kasper’s handwriting. Well, within a few weeks I introduced myself to the faculty and the students, and suddenly I was responsible for an institute I knew very little about.

HUO: I remember very clearly how you took over when Kasper moved to become director of the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. I came to Gasthof for that great event you staged with Rirkrit Tiravanija and students from all over the world. I also recall that during your first years you ran the school with Thomas Bayrle. His wife, the filmmaker Helke Bayrle, documented everything happening at the Portikus. It must be quite a unique archive.

DB: Yes, it’s quite unbelievable. And now it is online under the title Portikus Under Construction.1 I don’t think the backstage life of any other institution is as well-documented as the Portikus. It’s really fantastic material for anyone interested in exhibition production, and offers an unparalleled collection of artist portraits.

HUO: It’s funny that later you moved on to Moderna Museet in Stockholm, where Kasper made his very first exhibitions. He was surprisingly young when he organized projects there, even a legendary Andy Warhol exhibition when he was not yet twenty-five years old.

DB: The young Kasper was certainly good at being in the right place at the right time. Remember: in 1965, twenty-two years old, he arrived as an intern at the Robert Fraser Gallery, the epicenter of Swinging London. He was asked to transport a painting to New York, where he got to know Warhol and was given a job at The Factory. Three years later he was a cocurator of Warhol’s first museum exhibition with Pontus Hultén, the most inventive museum director at that moment.

HUO: The Warhol exhibition’s concept was Kasper’s, right? I mean the focus on flowers and electric chairs.

DB: Yes. And perhaps more importantly, the Brillo Boxes.

HUO: I remember that Kasper had one of the original ones from 1968. His TV used to be placed on top of it.

DB: I recently found the letter that Kasper sent to the CEO of Brillo to get empty boxes from the factory. A quite funny thing is that Kasper actually never saw the show he had conceived for Stockholm. He stayed in New York and managed to get the airline ticket that he didn’t use reimbursed so that he could pay his rent. He didn’t actually install the show.

HUO: But he edited the catalog, designed according to his ideas. That’s a wonderful book with Warhol flowers on the cover. An amazing book.

DB: Do you think Kasper saw himself as a kind of mentor?

HUO: I don’t think he would have used that word. But of course Hultén was his mentor. Kasper worked for him again at the Pompidou.

DB: And it was through Hultén that he could get his green card. For a few years in the 1960s he was officially Moderna Museet’s ambassador in New York.

HUO: Now we talk too much of the past. It’s more interesting to think of Kasper’s influence today and his importance for future forms of exhibition making.

DB: How did he influence your work?

HUO: In his Frankfurt office he had all these boxes. One for each artist. All the information went into the box: from flyers for exhibitions to photographs, letters, texts, books, and catalogs. I worked my way through these boxes at night. For me it became a kind of parallel school to the Städelschule. I could study all the material. This way of researching and archiving became a blueprint for my own approach. I copied his method.

DB: I think that there are more important things to discuss when it comes to exhibition making. Kasper invented so many new formats. He never just played along, he never accepted traditional institutional rules. Think about it: almost all of his important shows took place outside the settings where one would expect them. His two most significant group shows in the 1980s, the projects that established him as the most important curator in Germany—“Westkunst” (1981) and “Von Hier Aus” (1984)—happened at the trade fairs of Cologne and Düsseldorf, not at museums. That was his most important gift, his ability to invent new spaces for art.

HUO: True. The Portikus, originally just a container behind an old facade, is a strange idea. It turned out to function beautifully and developed into one of Europe’s most vibrant laboratories for art. And then there is the Sculpture Projects in Münster, also an invention of Kasper and his colleague Klaus Bussman—one of the most influential public art projects ever. And it is still around, fifty years later. It survived its inventors and will open again in 2027.

DB: Simply copying his inventions would not be the right way to pay tribute to Kasper. I guess it’s all about the creation of new spaces for art. That really is his legacy. You have invented some new formats too, like those hyper-intense marathons in cities across the world. Your constantly travelling “Do It” exhibitions. And your handwriting project on Instagram.

HUO: So have you, with all the recent virtual productions.

DB: Kasper was not a digital person at all, as you know. But he was the only older curator who was curious about the augmented reality shows I organized during Covid with Acute Art. Kasper came to London to understand more about it. We did all those group shows using augmented reality in the public space of cities and he saw the future potential of that medium.

HUO: Clearly a relevant medium for the Sculpture Projects.

DB: Yes. But do you remember Kasper’s “facebook”?

HUO: What?

DB: He referred to his enormous address book, a kind of assemblage work of art itself, as his “facebook.” “I’ll put it in my facebook,” he would say, and glue in some piece of paper.

HUO: I remember that book. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster has a great anecdote about it from the time she studied with Kasper. When some guest did not arrive on time to give a lecture, Kasper would simply read out of his address book in front of class. Name after name after name.

DB: Thinking about it, he liked lists. He wasn’t a great writer but he was a great creator of lists. But back to the main question: What is Kasper’s true legacy? I would say first of all: trust the artists.

HUO: He helped me realize that art can appear where you least expect it. To work with him when I was very young was an incredible learning experience.

DB: That’s another important lesson: involve younger people.

HUO: Later I realized this was part of his methodology—to always involve young collaborators and teach them the rules of the game. And above all to break the rules of the game and invent new ones.

DB: That’s it. Break the rules.

See →.