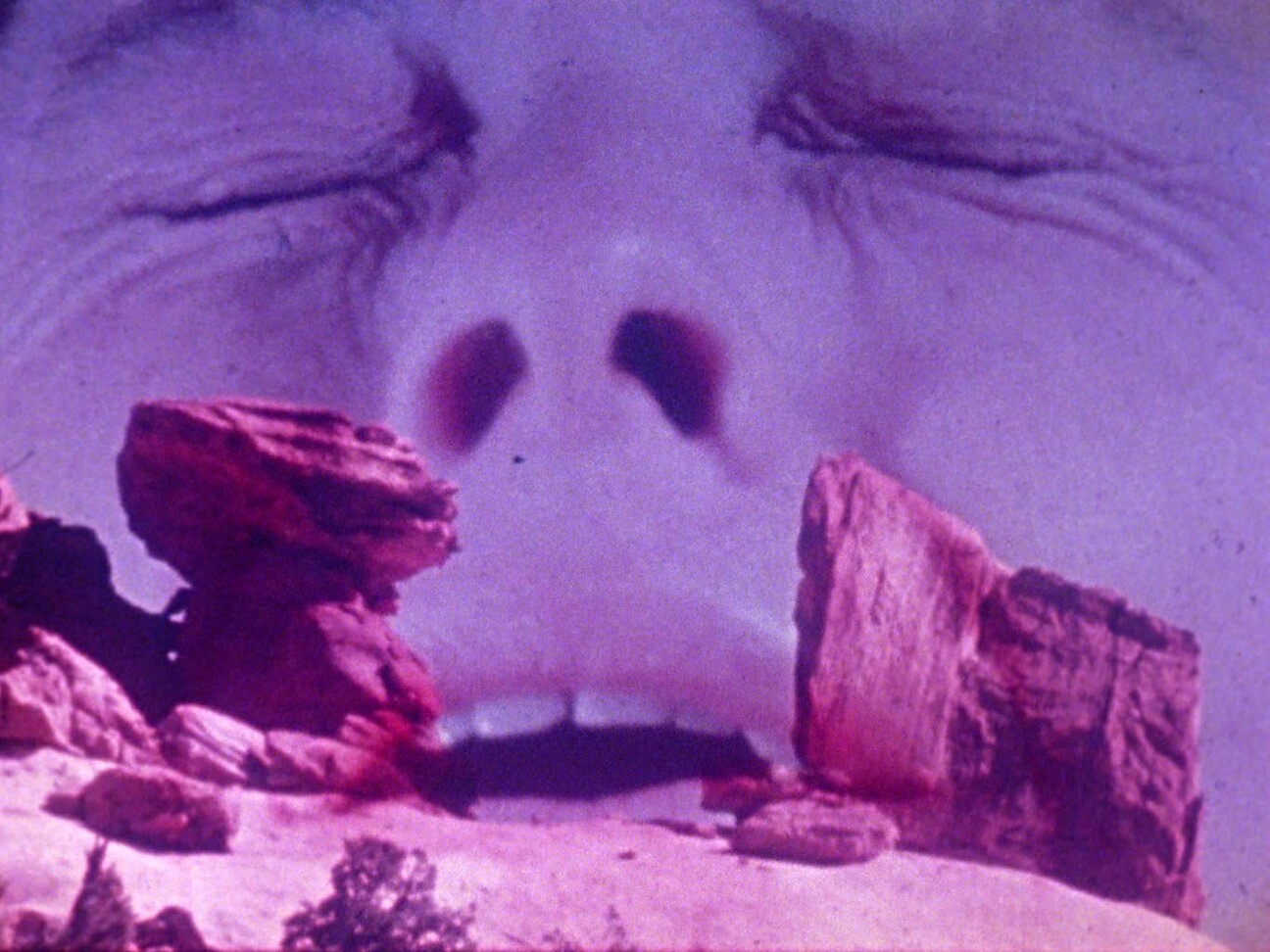

A still from Barbara Hammer, Multiple Orgasm (1978)

As an experimental filmmaker and lesbian feminist, I have advocated that radical content deserves radical form.1 In 1979 I had my first screening outside the supportive lesbian feminist community when Terry Cannon, then programmer at Film Forum in Los Angeles, asked me to show my films in a venue of experimental films. I had already completed several experimental films with lesbian feminist content and had shown them regularly in the Bay Area of San Francisco. They were also distributed by early women’s film cooperatives. In both cases I was called upon to explain my unorthodox form and content. To the feminist community, I introduced my films in light of the formal concerns of experimental filmmaking. To the experimental film community, I spoke about the importance of unrepresented content.

It is my belief that a conventional cinema, such as classical narrative, is unable to address the experiences or issues of lesbian and gay perceptions, concerns, and concepts. When an audience awaits the image on the screen it expects a heterosexual narrative to unfold, and the audience is not disappointed. Even if the characters are lesbian, the script projects lesbian characters within a heterosexual world of role-playing, lovemaking, and domestic and professional life. The numerous films that purport to be “lesbian films” have failed to address me as a lesbian spectator. The romance, the onscreen gaze, the plot, and the character development are all situated within a heterosexual life-style or a Hollywood imaginative life-style made for the cinema. Certainly the women I have seen on the screen, their issues, the story, and the mise-en-scène do not relate to the personal experiences I live and have lived as a lesbian woman for twenty-three years in the Western world.

Lesbian cinema is on an invisible screen. By the “invisible screen” do you mean pictures drawn in lemon juice backward that, when heated, can be read through a mirror? asked a friend. It has been that difficult to see lesbian representation in cinema. The lesbian imaginary is carried in a back pocket inscribed in invisible lines until heated by the projector lamp.

How could this be, in an age where we have films like Desert Hearts, Lianna, and Personal Best? These are films where the onscreen space is filled with seeming “lesbian representation.” But my reading of these films is that there is no lesbian to deconstruct, as the discourse of the gendered subject is within a heterosexist authority system. The lesbians act out heterosexual gender roles and positions rather than claiming any difference, and even sexual practices are situated within heterosexuality.

As a runaway from the political regime of heterosexuality, I and other lesbian filmmakers began to construct a lesbian cinema in the early seventies. Visibility was the central concern for lesbians making cinema at this time, for the simple and profoundly sad reason that there were few or no pictures, images, or representations available. The screen space, on and off, was blank. Not just marginalized, but not there. There was no cinema to deconstruct. There was no gaze to analyze. Lesbian image-makers in the seventies were forced by critics into the “camp of essentialists” because of the extreme urgency of their need to make lesbian representation. A marginalized and oppressed group must make a mark first, define a form, and make a statement that they exist. As we began to make films of lesbian representation, we were categorized by the emerging feminist semioticians and theorists (newly emerged themselves from French studies with Christian Metz) as “essentialists.” Because we made representations of lesbians, the false assumption was made that we invested these representations with biological, essential “meaningness” separate from ideology or social construction.

I, for one, as a lesbian cineaste, take a more eclectic and I hope eccentric view of the lesbian representations I made in the seventies. The lesbian women I imaged in film were constructed by the general and dominant society, as well as the marginal society of the lesbian community. In the process, we also discovered who we were, as we stepped into the void, the invisible, the blank screen, and named ourselves “lesbian.” That was the first step. There could be no semiotics if there were no sign. The lack we felt as we began this early naming process was not the lack of a phallus but the singular and significant lack of any representations. The image did not exist, the picture was not made, the word scarcely heard in discourse nor seen in text.

Until recently the dominant discourse of feminist criticism has not addressed this issue but has continued to ignore it, and by doing so perpetuates the invisibility and repression of lesbian cinema. To dismiss the early naming and identity films with the highly charged and emotive term “essentialist” further removes the opportunity for discourse in a climate where deconstruction, Marxist, psychoanalytic, and Lacanian theories prevail.

The reidentification of a lesbian self through lesbian sexual experience is one part of lesbian representation. There are many parts and practices of lesbian experience to be represented. In physics, light can be understood through wave and particle theories at the same time. So too can there be multiple, coexisting, and different theories and understandings of “lesbianisms” through a variety of readings. One of these readings is experimental cinema: the cinema that makes its own construct where form and content are inseparable. I don’t think one can make a lesbian film using a patriarchal and heterosexist mode such as the conventional narrative. Plot points are male points. We are radically changing people, and we cannot reproduce that radicality using conventional forms.

I have chosen images rather than words for the act of naming myself an artist and a lesbian because the level of meanings possible for images and image conjunctions seemed richer and held more ramifications. I have broken rules, studied the construction of norms, and questioned restraints since I was a little girl. It was not strange that I chose to practice in the longtime artistic tradition of breaking or modifying the status quo in an attempt to advance the dialogue. Generally speaking, my films made in the seventies, Dyketactics, Multiple Orgasm, Double Strength, Women I Love, and Superdyke, as well as others, were made with this intention that grew from an unconscious impulse to a conscious insistence on lesbian naming.

Once named, and identities established as artist and lesbian, I wanted to get on with other areas of expression that I had left unexplored. The second ten years of my nonnarrative film production focused on my perceptual interests. In my early films, I chose “realism” by using the camera as an eye, capable of defining form, outline, and depth to depict the lesbian body. The social realism of the scenes was contrasted with the dreamlike, metaphoric, and imaginative images of freedom. In the urgency to make lesbian imagery, I neglected my thrill of simply projected light even without images, and my love for abstraction.

Abstract or nonrepresentational art appeals to me for several reasons. I have deeper emotions when I’m working beyond realism because there are no limits, and I enter and engage with the dialogue between light and form. I am not presenting a statement or an essay, but a more amorphous work that allows the maker and the viewer the pleasure of discovery. Meaning is not apparent at first glance and often requires repeated screenings, promising challenge. The satisfaction that comes from study and understanding of a complex work of multiple references and perceptual insights is a very rich fullness that can’t be compared to linear journalism or narrative. Film allows me to express perceptual, intellectual, and emotional configurations that provoke pain and give pleasure.

The contributions of postmodernism have challenged the singularity and uniqueness of individual expression through the “utilization of forms over and above content due to the production of works in concrete historical circumstances.”2 The forms I choose are marked by the historic period in which I live, but the content of my work has not been remarked upon by modernists or postmodernists. Lesbian difference is ignored by both schools of theory. While I may enjoy the multiplicities of abstraction in form, it is still continually necessary to state my difference in content in my films, videos, performances, and writing. It is true that I bear the mark of the construction of perception by the social forces and institutions in which I live. Architecture, advertising, educational systems, family rearing, and Hollywood movies have all shaped my construction of knowledge and perception.

All these authority systems have “authorized certain representations while blocking, prohibiting, or invalidating others.”3 So even while I find pleasure and ambiguity in the formal characteristics I select for my films, I am still compelled to work from my experience from which my “subjectivity is semiotically and historically constructed.”4

As a working lesbian artist, I am using abstraction not only for the perceptual pleasure and multiple possibilities of meaning. but also because I believe the viewer must be active. The supposition I have made is that participatory behavior in one area can lead to participation rather than passivity in another. The passive reception of non-challenging visual media—broadcast television, commercial film and the pulp press, static or moving—encourages passivity in other modes of living (on the job, at home, in the streets, in politics). An active audience engaged in “reading the text” will also be active in making their own decisions about campaigns, elections, issues, and demonstrations. I also use abstraction because of the uncertainty principle that is the locus for a certain type of play. There is linear play, where each person accepts rules of behavior, dialogue, and dress, such as children playing nurse and doctor. Then there is an abstract kind of play which requires the active imagination, where the only rule is: anything goes. There can be abrupt changes of scenes and locations, gender, names, and all possibilities of expression are possible. This form of play for children or adults requires a strong sense of self. In abstract play, everything around you can be turned upside down, and the most unimaginable combinations of words might be spoken; the disruptions, flights, costumes, and fantasies will swirl around you. You must know you won’t be destroyed by letting go. Similarly, in letting the abstractions of light and texture, image and voice swirl around you and carry you into a filmic experience, you become aware of what you are experiencing. The active audience members don’t lose a sense of themselves while engaging in the physical sensations of abstract cinema, but feel more the possibility of being.

Finally, multiple readings, understandings, and namings are promoted by abstractions providing richness, diversity, and complexity. If it is any worldview we need right now to allow for preserving difference, it is a worldview that embraces flexibility, possibilities, and multiple understandings of phenomena. There is not a feminism but feminisms, not a lesbian cinema but lesbian cinemas, and there is not abstraction but multiple manifestations of abstraction.

Editor’s note: Barbara Hammer’s text “The Politics of Abstraction” was first published in 1992 in the journal Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory. It was later included in the anthology Queer Looks: Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Film and Video, edited by Martha Gever, John Greyson, and Pratibha Parmar, and published by Routledge in 1993.

Craig Owens, “The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1983), 58.

Owens, p. 59.

Teresa de Lauretis, Alice Doesn’t: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 182.