Hospital Little Lexington, 1964. Photograph by Ab Pruis, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam (CSD BG B23/888).

In the summer of 1964, Robert Jasper Grootveld—Dutch artist, odd-job laborer, and self-avowed magician—was arrested in central Amsterdam and forced to serve twelve days in jail. The reason for his detention was the anti-tobacco and pro-cannabis happenings he led at the Amsterdamse Lieverdje, or “Little Darling,” a life-size statue of a child on Spui square gifted by the Eindhoven-based Hunter Cigarette Company. Grootveld was no stranger to spending stints in prison. In fact, this latest punishment was part of a sixty-day sentence he received just a couple of years prior for scrawling on dozens of tobacco-company advertisement placards.1 Like his street actions at the Lieverdje, graffiti was part of Grootveld’s one-man campaign against the conformist Dutch middle-class, or “the addicted consumers of tomorrow.” Cigarettes were at the top of his list of the mainstream commodities to subvert. Adopting the alter ego of a sage or shaman-like healer, Grootveld would boisterously rail against the tobacco industry and the noxious effects of nicotine while singing the praises of marijuana. His over-the-top persona, with its coarse and exaggerated appropriation of exoticizing tropes, was intended as acerbic parody.2 A common ritual he enacted while in character was having people forego their cigarettes and toss them into a sacrificial fire at the feet of the Lieverdje, encouraging participants to cough in unison. On other occasions, Grootveld would wrap the statue’s neck with a cloth soaked in a flammable solution and let it burn. These happenings often ended with Grootveld being escorted away by Amsterdam police, who at the time enforced aggressive crackdowns on cannabis selling and possession—a far cry from the lenient stances towards soft drugs and coffee shops in the Dutch capital today.

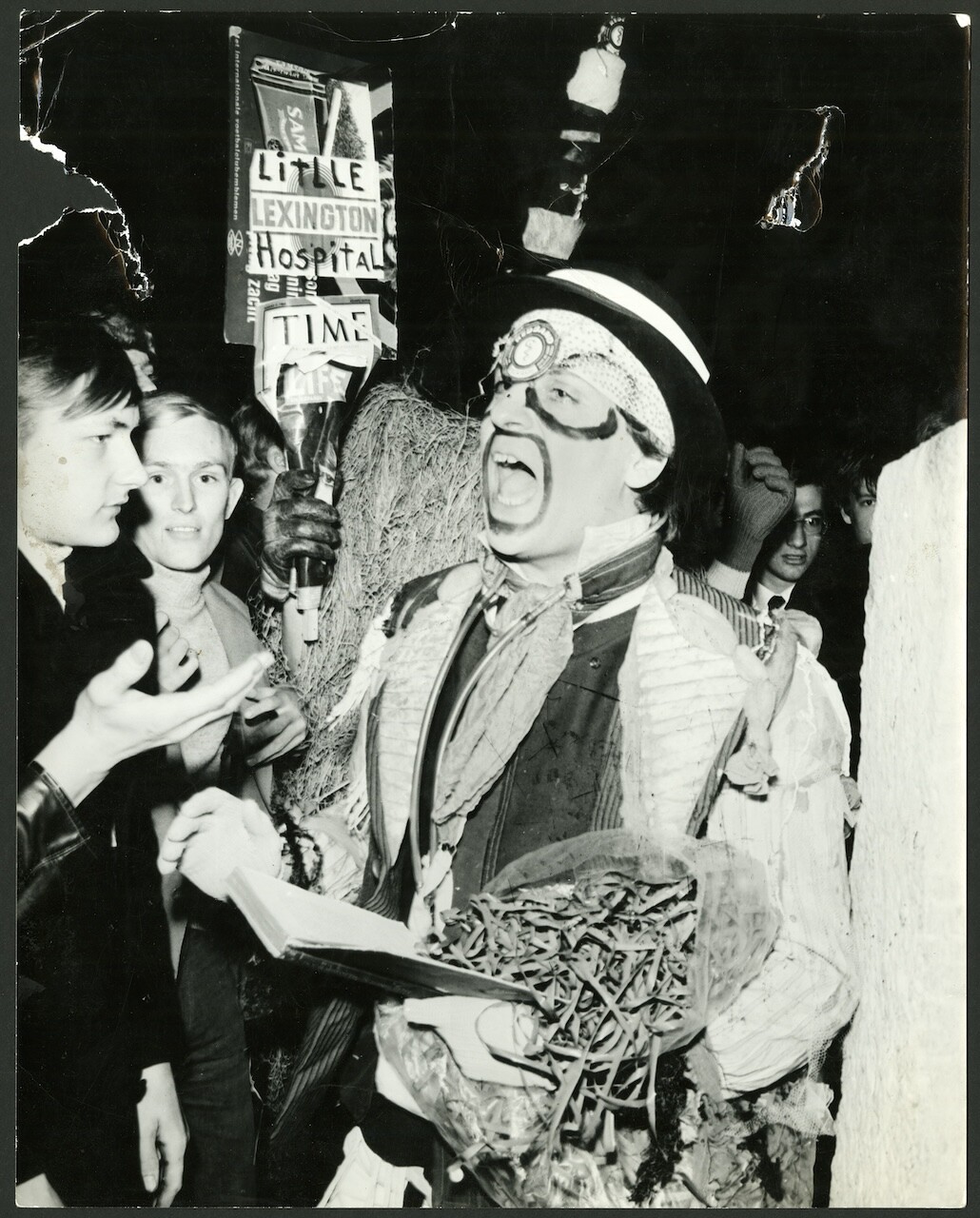

Robert Jasper Grootveld at a Hospital Little Lexington happening, 1965. Photograph by Cor Jaring. International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam (CSD BG B27/216-7).

That same summer, Martin Luther King Jr. addressed massive audiences in Amsterdam at the European Baptist Federation Congress, just weeks before his nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize. The Beatles performed several times across The Netherlands and the Rolling Stones had a memorable concert in The Hague—their first ever in continental Europe—which lasted only a few minutes before being shut down by police due to audience disruptions. Restless Dutch youth, who had trickled in to see Grootveld since he began his series of happenings that spring, began to steadily form crowds at the Lieverdje. Anarchists and left-leaning supporters also turned into regular attendees. In just a few months, these weekly gatherings would become an anchor for the Provo, a brief yet enormously influential movement known for its “provocations”—playful acts of antiauthoritarianism directed against Dutch law enforcement, local government, and the monarchy. Ahead of the May 1968 protests in Paris, the Provo gained attention across Europe as a youthful force of revolt, ignited in no small measure by Grootveld’s rebellious flame. Lasting only between 1965 and 1967, the Provo nevertheless shook up the country’s political establishment in ways that remain alive to this day. It was the Provo who laid the groundwork for the current broad-minded Dutch policies on gender equality, social housing, welfare services, urban transport, and of course tolerant drug use.

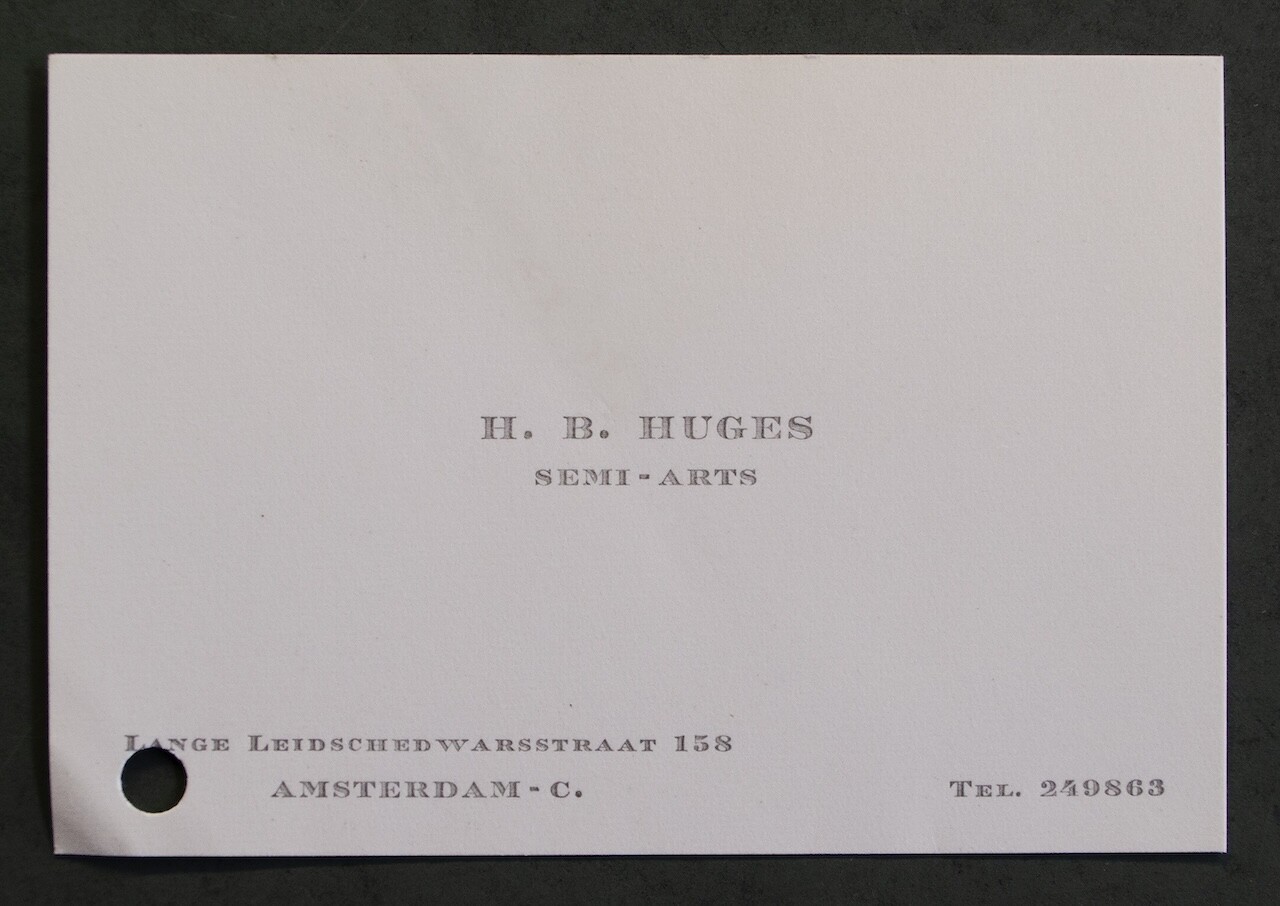

All this is an established part of the Provo mythos. Less well-known are its roots in preceding forms of emancipated living in Amsterdam—small-scale efforts that helped leverage far-reaching collective action in the city. Often, these experiments happened inside traditional domestic spaces or those otherwise occupied and transformed into a home. A case in point is Grootveld’s dwelling in Leidseplein, then an alternative bohemian neighborhood in the heart of the city. Between October 1962 and March 1964, Grootveld lived at Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158 in the Oude Kothuys, or the “old cottage,” a house slated for demolition. He stayed there with his close friend Bart Huges, a Dutch medical student and fellow pro-cannabis advocate who first moved in with his wife Barbara Mohr. Paying rent under the table, Huges and Mohr set up a squat, outfitting the rooms with basic yet serviceable plumbing, heating, stoves, beds, and furniture.3 Grootveld would soon take up residence with sculptor Nettie Dagoves, a tenant at the same address (and amusingly the granddaughter of a Dutch tobacco entrepreneur). Upon his arrival, Grootveld marked the outside of the building with an apple and a dot, or the “gnot” symbol, which he and Huges designed earlier that year to represent Amsterdam as a “magical center”; the name of the symbol was a neologism that combined the Dutch words “genot” (pleasure) and “gnost” (gnosis).4 The timing of Grootveld’s move overlaps loosely with the loss of his previous base: a garage at Korte Leidsedwarsstraat 38, a stone’s throw away from the Oude Kothuys. Called the “K-Kerk,” or “K-Church” (the “K” standing for “kanker” or “cancer” in Dutch), the location accidentally burned down after one of his performances, but was immortalized in the 1962 short film Jasper en het rokertje (Jasper and the cigarette) by Louis van Gasteren, Dutch filmmaker and a friend of both Grootveld and Huges.

From the beginning, Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158 had a steady stream of visitors. Some would stay overnight, others for much longer. The open spirit of the household was not unlike the home of Tanja van der Geest at the nearby Leidsekade 83. A former singer at Amsterdam’s legendary Lucky Star Club, she had the reputation of being a mother figure for the down-and-out of Leidseplein, taking in anyone who did not have a place to sleep for the night. In his 1965 diaristic novel Love: Seventy Days at Eye Level, penned in part at van der Geest’s address, Dutch poet Simon Vinkenoog wrote:

The house at number 158 was a living being with functioning organs … There was always gas, water, electricity, a telephone, a bath, a toilet, burning stoves. There was no shortage of anything, except the necessary evil—and what’s more, most have come out all the better because of this. The house was under high protection and served as a stopping point for many; I am happy and proud to have experienced it as a friend of the household …

Everyone had access to the typewriter, where we stood by pushing each other to take turns. Entire pages were filled. The most moving lines were Mel’s. I keep them with me wherever I go. What does the neighborhood know about the house where they saw the happy many enter? [original emphasis].

That was why the house was so sacred, a place where poets enjoyed hospitality, where games, parties and rituals defined the world of tomorrow.5

Besides Vinkenoog, several avant-garde poets would call Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158 their physical or figurative home. The “Mel” that Vinkenoog refers to is most certainly Melvin Clay, a US actor, author, and film director who settled in The Netherlands and had close ties to Allen Ginsberg and the Beats. Lee Bridges, known as the “Cannabis Poet,” likely keyed verses at the typewriter, having traveled from New York in 1963 to read his poems in Amsterdam cafés.6 A regular lodger was Johan van Doorn, or Johnny “The Self-Kicker,” a Dutch poet renowned for his visceral sound performances, who had recently arrived from Arnhem. He describes finding shelter at the Oude Kothuys along with “hundreds of house mice who lived an undisturbed life behind the wallpaper,” some stoned enough to eat out of his hand or fall into his mouth while he was asleep.7

In short order, the communal quarters at Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158 would bear the title of “Hotel,” specifically “Hotel Little Lexington.” The name was a nod to a popular cigarette brand in The Netherlands (no doubt Grootveld’s idea) and to the famed Hotel Lexington in New York City, as well as to the Lexington Narcotics Farm, a US federal rehabilitation center in Kentucky.8 Among those admitted to the Lexington Narcotics Farm for addiction were the boxer Barney Ross, singer and actor Sammy Davis Jr., jazz musicians Chet Baker and Sonny Rollins, and Beat writer William Burroughs. Patients would be remitted as inmates or check themselves in as volunteers. In addition to the unparalleled celebrity company, a strong draw was that hard drugs were among the treatments available to residents. True to this namesake, the creative zeal and access to drugs was replicated at Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158. Those wishing to get high were welcome and could benefit from Huges’s care and supervision. As a semi-arts—the Dutch term for medical students in their final year—Huges effectively served as the house doctor while studying for his certifying exams and training at the Wilhelmina Gasthuis, and then the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Amsterdam. Before long, this element would be reflected in the new designation of the house as “Hospital” Little Lexington, living up to its own repute as a gasthuis: a Dutch word that simultaneously means both “hotel” and “hospital.”

Calling card for Hugo Bart Huges. Bart Huges Archive, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam (ARCH04350, Box 1, Folder 3).

Huges’s own first-hand understanding of drugs began in 1958 when he was a research subject for behavioral experiments with LSD in the psychiatry wing of the Wilhelmina Gasthuis.9 He experienced the effects of marijuana for the first time during a trip to Ibiza in 1962 and soon after tried mescaline, which could still be procured legally via pharmacies or chemical suppliers. At Hospital Little Lexington, Huges would impart insights on safe drug consumption to strangers and friends alike. Vinkenoog, an old acquaintance who participated in the same medical experiments with LSD, called on him regularly for advice regarding psychedelic drugs.10 Without a doubt, his time at Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158 only further strengthened Huges’s convictions about the psychiatric and neurological benefits of psychedelics. Together with Barbara, he self-published his thesis on increasing blood volume to the brain to gain higher levels of consciousness. In 1965, Huges would gain notoriety for following his own propositions by boring a hole in his frontal bone—a third eye he asserted would provide the feeling of a permanent high.11 His trepanation would soon become associated with the gnot, the dot and the apple symbolizing the perforation of his skull.

Huges’s vocal positions on marijuana garnered a fair amount of media attention well before his bold self-experiment. The controversial headlines he generated in local newspapers would account at least in part for the University of Amsterdam’s refusal to grant him a medical degree. Yet it was at Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158 where Huges built up his professional chops as a doctor. He had already advised audiences at Grootveld’s K-Kerk on how to take mind-altering substances.12 At Hospital Little Lexington, he could formulate hypotheses on the role of glucose levels and vitamin C intake under the influence, dispensing drugs and therapeutic care intermittently within a nonpunitive setting. Although active for only a brief period, the significance of places like Hospital Little Lexington cannot be overstated. No matter how makeshift or short-lived, these spaces prefigured Amsterdam’s progressive approach to drug usage, focusing on treatment and harm-reduction rather than criminalization. Not surprisingly, drug addicts and runaway youth sought refuge there, as likely did other marginalized members of Dutch society denied public health services due to economic cost or social exclusion.13

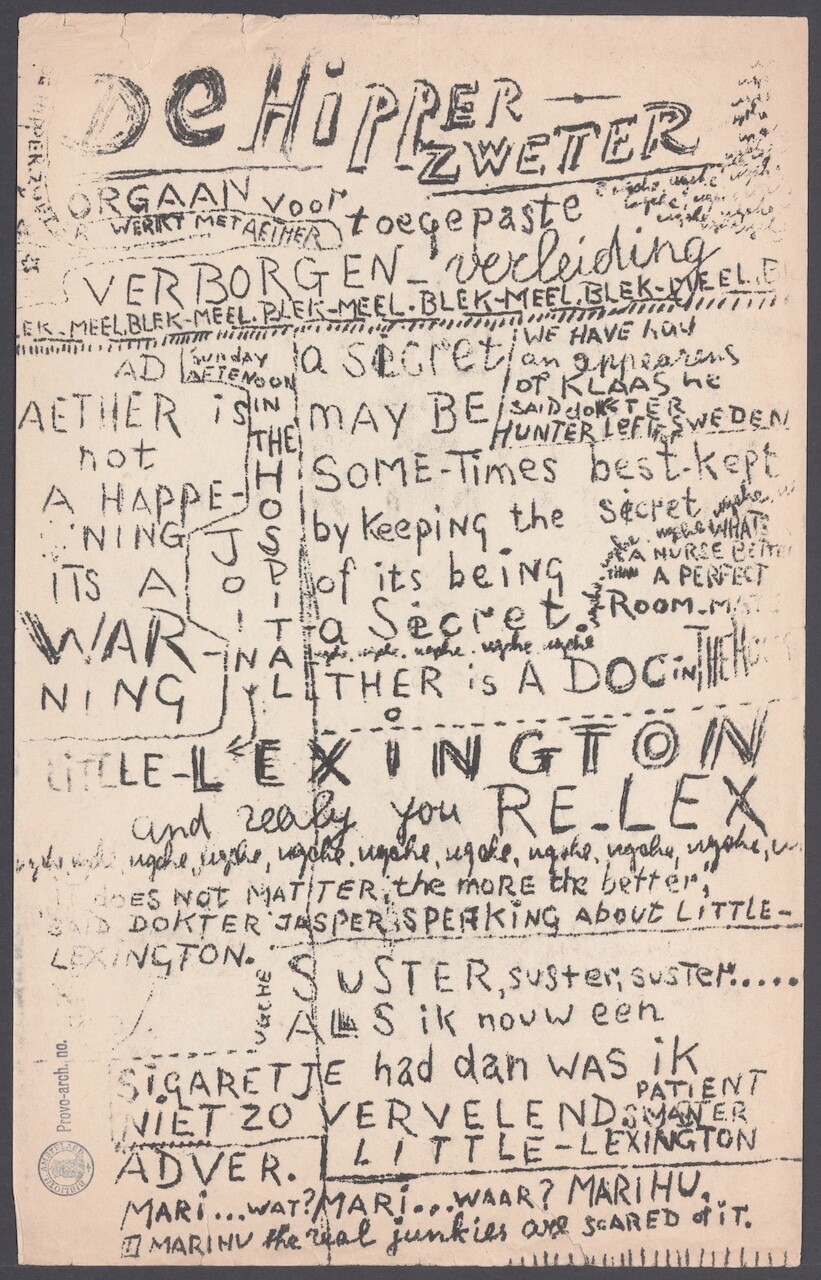

Robert Jasper Grootveld, De Hipperzweter, n.d. Provo Archive, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam (ARCH02080, Box 26, Folder 2).

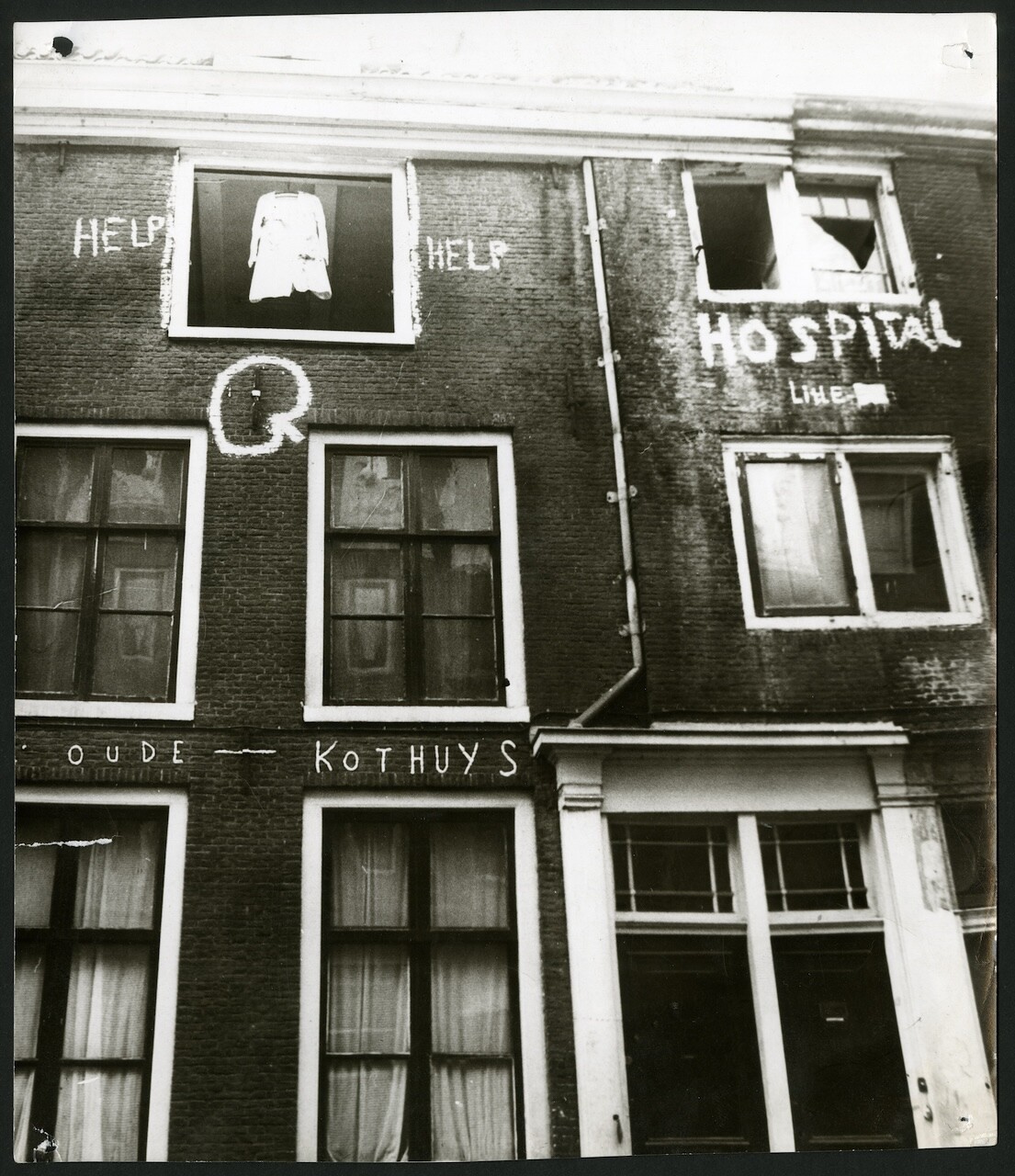

Grootveld would exalt Hospital Little Lexington in overt and tacit ways, both throughout the duration of his stay and after the building was gone. Hints about its location were scattered throughout De Hipperzweter, a “newsletter” he produced on copy paper with a stencil machine to announce his performative actions, spread information, and answer questions from journalists. Following the demolition, he launched his happenings at the Lieverdje, brandishing collage-covered picket signs reading “Hospital Little Lexington” and turning this site into both a rallying cry and a cause. Photographs from one of these events show Grootveld wearing what appears to be a stethoscope around his neck and a tin of Redband lozenges on his forehead. The tin features a prominent caduceus: a medical symbol that aligns with Grootveld’s self-fashioning as a healer, but which may also allude to Huges. Before Hospital Little Lexington was knocked down, Grootveld hung on the top window a long white garment resembling a doctor’s overcoat, one that could have belonged to Huges himself. Anonymous film footage from the time shows Grootveld wearing this robe as he rushes into the dilapidated building—a last urgent gesture of having a doctor on call, even in a vacated house. According to Vinkenoog, it was also Grootveld who made the whitewashed inscriptions across the entire façade. The word “Help” appears repeatedly alongside “Hospital Little Lexington” and the three crosses of Amsterdam’s coat of arms, with the gnot still overhead “like the flag above an oasis,” one that would soon disappear “to make way for a larger whole.”14

Hospital Little Lexington, 1964. Photograph by Ab Pruis, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam (CSD BG B27/268).

In Vinkenoog’s account, Hospital Little Lexington was razed in ten days starting on March 18, 1964. Marking sixty years since its disappearance, 2024 is also a two-fold anniversary for Bart Huges; ninety years since his birth and twenty after his death. Those who walk past Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158 will find no commemorative plaque about him, Grootveld, or any other former inhabitants of the house. A children’s playground now stands in its place—a mirror image of the uninhibited vim of its former existence. As with many squats, an unrecorded absence belies historic and enduring importance. The influence of Hospital Little Lexington remains in the legacies of the Provo, not least in the gnot symbol, which the movement claimed as its own, turning the apple’s contour into Amsterdam’s outermost canals and the dot into the Lieverdje itself. “No holy house exists (not even Lange Leidsedwarsstraat 158),” Vinkenoog pronounced after learning about the forced eviction of its residents.15 Walking through the gutted structure of Hospital Little Lexington and the piles of objects left behind, he recognized Grooteveld’s abandoned newspaper clippings, advertisements, and posters related to nicotine and cancer. Amid the debris, he rescued a photograph of the K-Kerk. “That Amsterdam possesses a magical modern artist in him,” he pondered, “nobody knows.” Sometime later, Vinkenoog came upon the De Hipperzweter announcement for the happening where Grootveld was arrested. Lingering on a drawing of the gnot and the three Amsterdam crosses signaling “mercy, generosity and determination,” he avowed:

We make Amsterdam come true. A city full of love.

Even though people wish not to know.We will make it known.

In all ways.16

This article is part of Ø (1962–65), a research project centered on Bart Huges and Hospital Little Lexington. Special thanks to Dr. Jelle de Wit for his research and translation assistance and to the International Institute for Social History for image permissions, as well as to the Mondriaan Fonds and Amsterdamse Fonds voor de Kunst for their financial support.

Wim Art Louis Beeren, Actie, werkelijkheid en fictie in de kunst van de jaren ’60 in Nederland (Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1979), 31–34.

Janna Schoenberger, Waiting for the Witch Doctor: Robert Jasper Grootveld’s Scrapbook and the Dutch Counterculture (Rijksmusem Studies in History, 2020), 44–54. See also Sven Lütticken, “Piete Zwart and Zwarte Piet,” Project 1975: Contemporary Art and the Postcolonial Unconscious, ed. Jelle Bouwhuis and Kerstin Winking (Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam and Black Dog Publishing, 2014), 31–52, 45–47.

Bart Huges, The Book with the Hole: Autobiography, trans. Joe Mellen and Amanda Fielding (Foundation for Independent Thinking, 1972), 80.

Eric Duivenvoorden, Magiër van een Nieuwe Tijd: Het Leven van Robert Jasper Grootveld (De Arbeiderspers, 2009), 221–23. See also Huges, Book with the Hole, 80.

Simon Vinkenoog, “February 29, 1964,” in Liefde: Seventig dagen op ooghoogte (De Bezige Bij, 1965), 72–76. The reference to writing in Tanja van der Geesten’s home is from the entry “September 14, 2004” in Vinkenoog’s Kersvers → (in Dutch).

See, for instance, typewritten manuscripts by Lee Bridges such as The Dichter van het Leidseplein (January 3, 1963), Enkele gedichten van de zwervende Dichter (January 30, 1964), and The Wandering Poet-De Dichter (February 6, 1964), Bart Huges Archive, ARCH04350 (Box 1, Folder 3), International Institute for Social History.

Johnny van Doorn, Een magistrale stralende zon: Alle verhalen (De Bezige Bij, 2001), 40–41.

Nancy Campbell, J. P. Olsen, and Luke Walden, The Narcotics Farm: The Rise and Fall of America’s First Prison for Drug Addicts (Harry N. Abrams, 2008).

Joe Mellen, “Bart Huges: Questioned by Joe Mellen,” The Transatlantic Review, no. 23 (1966): 32. See also Huges, Book with the Hole, 46–47.

Stephen Snelders, “From Psychiatric Clinics to Magical Center: LSD in The Netherlands,” in Expanded Mindscapes: A Global History of Psychedelics, ed. Ericka Dyke and Chris Elcock (MIT Press, 2023), 364.

Bart Huges, Homo Sapiens Correctus scrolls, 1962–65. See also Suikergoed en marsepein (Barbara Huges, 1968).

Janna Therese Schoenberger, “Ludic Conceptualism: Art and Play in The Netherlands, 1959 to 1975” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 2017), 163.

De Schatkamer van Amsterdam (Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Gemeente Amsterdam, 2023), 34. See also Niek Pas, Provo! Mediafenomeen 1965-1967 (Wereldbibliothek, 2015), 51.

Vinkenoog, “February 29, 1964,” in Liefde, 72–74.

Vinkenoog, “March 19/20, 1964,” in Liefde, 182.

Vinkenoog, “June 12, 1964,” in Liefde, 289.