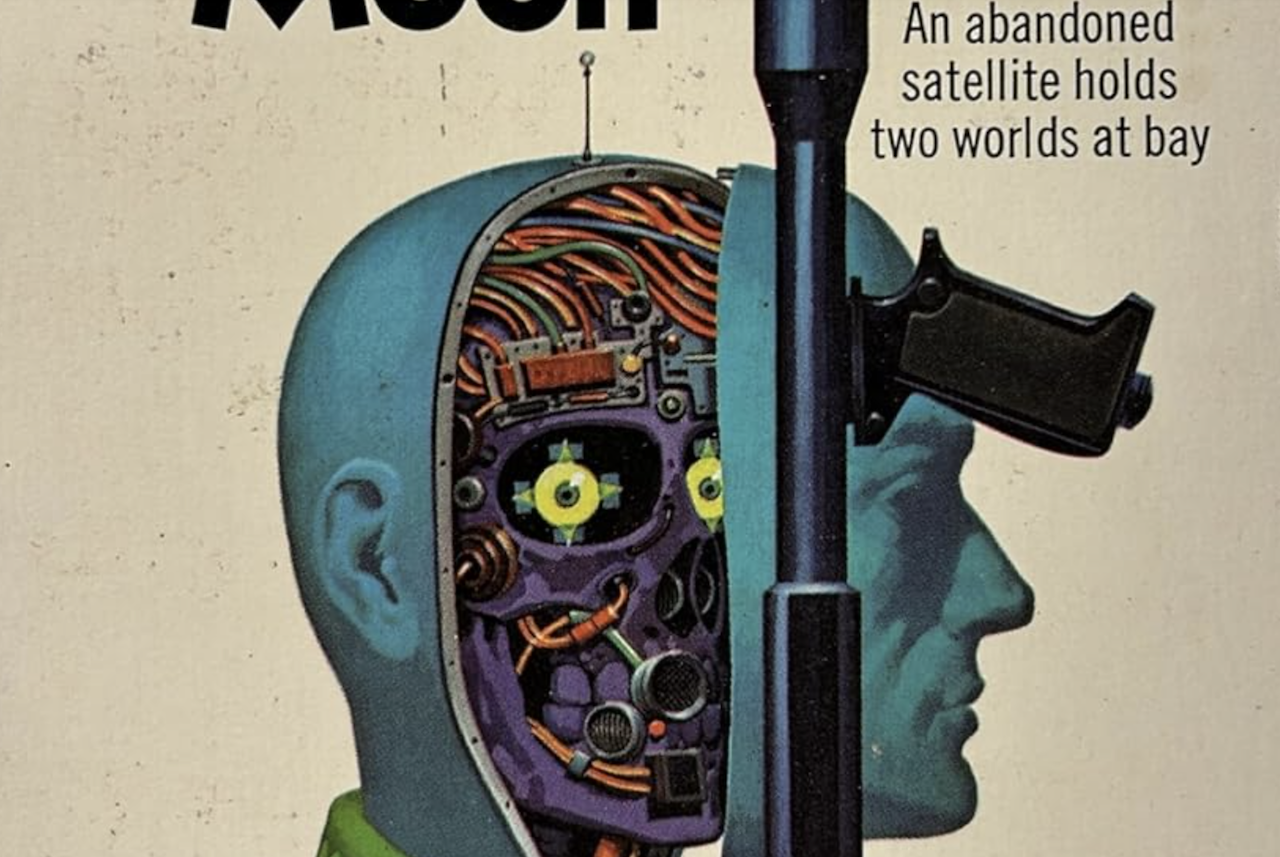

Cover detail of Philip K. Dick, Clans of the Alphane Moon (1964).

This is the introduction to David Lapoujade’s Worlds Built to Fall Apart: Versions of Philip K. Dick, translated by Erik Beranek. Published with the permission of University of Minnesota Press and Les Éditions de Minuit.

***

I’m surprised at you … Really, I am. You sound like a college sophomore. Solipsism—skepticism. Bishop Berkeley, all that ultimate-reality stuff.

—Philip K. Dick, The Man Who Japed

SF thinks with worlds.1 Creating new worlds with different physical laws, different conditions for life, different life-forms, and different political organizations; creating parallel worlds and inventing passages between them; multiplying worlds—such is the essential occupation of SF. The war of the worlds, the best or worst of all worlds, and the ways the world comes to an end are its recurring themes. Sometimes these worlds belong to distant galaxies, sometimes they are parallel worlds accessed through secret portals or breaches in our own world, and sometimes they take shape following the destruction of the human world. The only condition is that these worlds be other—or, when we are dealing with our own world, that it has been rendered sufficiently unrecognizable to have become other. We might even say that SF occupies itself with destroying worlds. The total wars, cataclysms, alien invasions, fatal viruses, apocalypses, and other kinds of end-of-the-world we find in SF are countless. There are numerous possibilities, but in each case it is a question of thinking in terms of worlds.

The trade-off is that SF struggles to create singular characters like those produced by classical literature. There is no Achilles, Lancelot, or Mrs. Dalloway in SF. Its characters are often ordinary individuals, stereotypes or prototypes that are only minimally individual, because they are primarily there to make us see the way a world functions or comes apart.2 Their value lies in their being indicative samples. At the limit, the character himself doesn’t even matter, as long as he makes you understand the laws that are obeyed by the world he is confronted with. The characters are never as important as the worlds in which they live. Given the conditions of some world or other, how do the characters adapt? Given a group of characters, what strange worlds are they confronted with? Such are the two principal questions that animate the stories of SF. One way or another, the characters are always secondary with respect to the world in which they are immersed or from which they are seeking to escape.

It will be objected that the truly distinctive trait of SF is its recourse to “science,” which is why we speak fittingly of science fiction.3 But here, too, science—and technology—are only means (now inherent to the genre) of propelling us toward distant worlds or of introducing us into a technologically advanced, future world. Perhaps recourse to “science” is what makes SF stand out, but it is nevertheless not what defines it. To speak like Aristotle, science and technology are properties of SF, but they do not define it.4 However important they may be for the genre, they remain subordinate to the invention and composition of other worlds.

This also explains why SF borrows from other forms of thought that conceive or imagine other worlds, such as metaphysics, mythology, and religion. Instead of a scientific dream, doesn’t each SF author really harbor a mythological, metaphysical, or religious dream, which is expressed through the creation of these other worlds? It is because they conceive of new worlds that Cyrano de Bergerac, Fontenelle, and Leibniz have been seen as precursors to SF. In philosophy, it is certainly Leibniz who has gone farthest along this path, because, for him, everything is thought in terms of worlds, and because the real world is always only one world among an infinity of other possible worlds.5 In addition, the way in which SF is frequently invoked today with regard to technological progress, the devastation of the earth, and utopian or dystopian visions also bears witness to a thinking with worlds, to “world effects” provoked by flows of information. It could be said that the horizon of each piece of information is now the viability, survival, organization, and destruction of our world, and, internal to that, the relations between the various human, animal, vegetable, and mineral worlds, inasmuch as they compose or decompose the unity and variety of this world. Information no longer bears upon isolated parts of the world without concerning the state of the world in general and its insurmountable limits. It is no longer the case that each event is connected to the destiny of the world by one or a thousand threads; now, the destiny of the world hangs on the thread of each piece of information.

That is why information is tending to disappear, being replaced instead by alerts. The informer becomes a transmitter, an alert vector in a permanent and generalized system of alerts that is tied to the political, economic, social, and ecological state of the world, taken in its entirety. And the information itself is always more alarming, always more terrifying, and supported by data concerning the ongoing destruction of the world. Isn’t that inevitable when the viability of the world—and of the multiple worlds composing it and giving it its consistency—is everywhere under threat? We aren’t informed about parts of the world anymore but are on permanent alert about the general state of the world. The effect is debilitating. All the scenarios, all the simulations and hypotheses that result, whether catastrophic or not, force us to think in terms of worlds, to “globalize” even the most minute data. And that is where the junction between the actual world and SF occurs, independently of the fictional stories, as if the information concerning the present state of the world were nothing but a succession of stories anticipating its future state.

Every author no doubt has a manner all his own of creating worlds; but, if there was ever an author who was fully aware of the necessity of doing so, it was Philip K. Dick. “It is my job to create universes, as the basis for one novel after another. And I have to build them in such a way that they do not fall apart two days later. Or at least that is what my editors hope.” And he immediately adds: “However, I will reveal a secret to you: I like to build universes that do fall apart. I like to see them come unglued, and I like to see how the characters in the novels cope with this problem. I have a secret love of chaos. There should be more of it.”6 Dick certainly responds to SF’s imperative to create worlds, but his worlds have the peculiarity of falling apart extraordinarily quickly, as if they didn’t have a solid enough foundation to remain standing on their own, or as if they were lacking in reality.

His worlds are unstable, susceptible to being distorted and overturned by the events that penetrate them and dissipate their reality. That, for instance, is what an employee discovers one day when he leaves for work earlier than usual and suddenly sees the world around him disintegrate into dust. “A section of the building fell away. It rained down, a torrent of particles. Like sand.”7 Once at work, he learns that a team of technicians, having been alerted by a local desynchronization problem, had suspended the reality of a part of the world in order to execute a readjustment. Or, in the short story “Exhibit Piece,” an employee of the Archives, who is admiring a meticulous reconstruction of the twentieth century, finds himself so completely transported into the scene that he ends up asking himself if the actual world (we are in the twenty-second century) might not itself, after all, be a reconstruction. “Good God, Grunberg. You realize this may be nothing but an exhibit? You and everybody else—maybe you’re not real. Just pieces of this exhibit” (S3, 194).

Or there is the novel Time Out of Joint, whose main character, a quiet denizen of a small town, sees the world around him undergo strange alterations. A soft-drink stand vanishes into thin air before his eyes, replaced by a small slip of paper with the words “SOFT-DRINK STAND” printed on it in block letters. As the phenomenon repeats itself, he decides to lead an inquiry into the reality of the world. How to interpret these slips of paper that resemble something like stage directions? Could someone be trying to deceive him? Maybe he has gone mad or is even in the center of a vast conspiracy of mass manipulation? To find out, he tries to flee the town, but “they” won’t let him. Why? “They’ve gone to a great deal of trouble to construct a sham world around me to keep me pacified. Buildings, cars, an entire town. Natural-looking, but completely unreal.”8 Is the hypothesis of the archivist in “Exhibit Piece” correct? Is the entire town an exhibit model on the human scale?

This is a recurring problem in Dick’s worlds. We don’t know to what extent these worlds are real or not, or whether they will reveal themselves to be as illusory as an amusement park like Disneyland. It will be said that Dick’s ambition is not to construct worlds, but to show that all worlds, including the “real” world, are artificial, sometimes being mere artifacts and sometimes being collective hallucinations, political manipulations, or psychotic deliria.9 This accords with the many statements in which Dick affirms that all his books revolve around a single problem: What is reality?10 What is real? Many commentators have taken up this question and made it the guiding thread of his work, thereby giving it an ontological or metaphysical dimension. But this does not explain what makes his worlds so fragile and changeable. Why is it that his worlds fall apart so quickly?

It is because behind this general problem there lurks a more profound one: that of delirium. For Dick, to be delirious is not just to create or exude a world, but also to be completely convinced that that world is the real world. No other SF author presents as many delirious characters, constantly threatened by or suffering from madness. His universe is populated with psychotics, schizos, paranoids, neurotics, etc., but also with mental health specialists, psychiatrists, psychoanalysts, and paranormal healers. And, at one point or another, they all come up against the question of delirium: Doctor, am I getting delirious or is the world going haywire? For instance, the archivist in the twenty-second century decides to consult a psychiatrist. “Look, Grunberg. Either this is an exhibit on R level of the History Agency, or I’m a middle-class businessman with an escape fantasy. Right now I can’t decide which” (S3, 196). This isn’t only the case for the characters who are mad, but also for those taking drugs and medications, for those whose memories have been tampered with, and for those whose brains are being controlled by extraterrestrial beings or a virus. With nuclear wars, irradiated nature itself begins to grow delirious; it makes bodies delirious, as can be seen in the aberrant mutations of the surviving species, like the “symbiotics” of Dr. Bloodmoney, “several people fused together at some part of their anatomy, sharing common organs,” one pancreas for six people.11 Nothing escapes the power of delirium.

If we want to retain the traditional definition of SF as an exploration of future possibilities, then these possibilities need to be delirious. “The SF writer sees not just possibilities but wild possibilities. It’s not just ‘What if …’ It’s ‘My God; what if.”12 With this simple description, Dick gives us one of the most profound aspects of his oeuvre. For him, it isn’t just a question of being imaginative, of inventing new worlds with new laws of physics, bizarre biological environments, and utopian political systems. Inventions of these sorts certainly feature in Dick’s work, but they aren’t essential. If the possibilities are to be “delirious,” they must refer back to an underlying madness, to a real danger that threatens, at each moment, to send us toppling over the brink into madness. It is therefore less a question of freeing ourselves from the real world in order to imagine new possible worlds than of descending into the depths of the real in order to figure out which new deliria are at work there. Compared to earlier classics, Dick is much closer to Cervantes and the deliria of Don Quixote or to the Maupassant of “The Horla,” than to Cyrano de Bergerac’s A Voyage to the Moon or to the novels of Jules Verne. The powers of delirium are of a much more disquieting nature than the possibilities of the imagination, because they make the very notion of reality stagger and lurch.

Without a doubt, the strangeness of the worlds found in SF tends to disorient its characters, to confront them with irrational situations that seem destined to make them lose their minds. SF needs this irrationality as one of its essential components, even if everything is explained in the end and the hero regains his reason. In Dick’s work, however, madness insinuates itself everywhere, affects everyone, and is just as often produced by extraterrestrials and drugs as it is by the social order, marriage, and political authorities. Even everyday objects go on the fritz and stop behaving the way they should. A coffee machine no longer offers coffee, producing little cups of soap instead. A door refuses to open, declaring: “The paths of glory lead but to the grave.”13 Computers grow paranoid or appear to be psychotic. “We have here a sick, deranged piece of electronic junk. We were right. Thank God we caught it in time. It’s psychotic. Cosmic, schizophrenic delusions of the reality of archetypes. Good grief, the machine regards itself as an instrument of God!”14 Many people believe that they get Dick’s work when they make him the author par excellence of an ontological or metaphysical interrogation (“what is reality?”), but, for him, the question is primarily of a clinical order. The ontological and metaphysical dimensions are not merely flights of imagination but point to questions relating to mental health and the dangers of madness.

We can see why he became an SF author, though he also wrote conventional, “realist” novels (which also feature delirious characters). Maybe the realism of the conventional novel deprived delirium of its force. If you accept the assumption that there only exists one “real” world, then deliria will inevitably be treated as secondary realities that are relative, pathological, and, in short, “subjective.” But if, on the other hand, you go back to the traditional definition of SF as an exploration of possible worlds, you no longer need to grant any primacy whatsoever to the “real” world, even if the majority of SF authors do ultimately preserve a form of realism that accords with their own world. The advantage of SF, for Dick, is that the real world is only ever one world of many, and not always the most “real” among them.

What does the force of delirium consist in? We could certainly think of the delirious person as being cut off from communal reality, enclosed in “his” world with his hallucinations, his erroneous judgments, and his extravagant beliefs. The criterion is not the delirious idea taken on its own—what idea isn’t delirious when taken on its own?—but the force of conviction that accompanies these ideas and hallucinations. No evidence, refutation, or demonstration can succeed in making the slightest dent in this conviction. Understood in this manner, delirium is defined as the creation of a world, but of a private, “subjective,” solipsistic world to which nothing in the “real” world corresponds, other than the elements that “send signals” to the delirium. The delirious person is lodged in the heart of a private world, the sovereign occupant at its center.

Given this conception, however, the psychologist Louis A. Sass finds the following paradox to be astonishing: How is it that delirious subjects accept the reality of certain aspects of the external world, even though those aspects enter into contradiction with their delirium?

It is remarkable to what extent even the most disturbed schizophrenics may retain, even at the height of their psychotic periods, a quite accurate sense of what would generally be considered to be their objective or actual surroundings. Rather than mistaking the imaginary for the real, they often seem to live in two parallel but separate worlds: consensual reality and the realm of their hallucinations and delusions.15

How do they succeed in making these two worlds coexist? The explanation is linked to another characteristic feature of delirium: the delirious subject takes the “objective,” real, or common world to be false. We often insist on the fact that delirium moves in an unreal and extravagant world, cut off from all external reality; but, in doing so, we overlook the other side of the coin, namely, that when he enters into contact with the external world, even when he does so with the best will in the world, the delirious person believes himself to be confronted with a false, artificial, or illusory world. And here is how the paradox is resolved: the delirious person agrees to interact with the “real” world, but only because he does not believe in its reality. He doesn’t submit to the reality of this world, he merely plays along.

Instead of viewing this as a paradox, should we not view this as a struggle, as a perpetuation of the already ancient struggle between the madman and the psychiatrist? The psychiatrist constantly repeats to the delirious person: you are not in the real world, your deliria are completely illusory. And the delirious person then responds to the psychiatrist: you are not in the true world, your reality is completely false. The former poses the problem in terms of reality, the latter in terms of truth.16 The psychiatrist’s argument consists in saying: there is nothing in your world that could be considered real. The madman’s argument consists in saying: there is nothing in your world that couldn’t be considered false. The one enforces the authority of the reality principle with his constraints; the other promotes the powers of the false with his deliria.

In certain respects, this is close to the form of struggle Michel Foucault describes in his lectures on Psychiatric Power. What the psychiatrist wants above all else is to impose a form of reality on the madman, using all the means he has at his disposal in the asylum, and to such an extent that “asylum discipline is both the form and the force of reality.”17 But the madman never stops returning to the question of truth through the way in which he simulates his own madness, “the way in which a true symptom is a certain way of lying and the way in which the false symptom is a way of being truly ill,” but also through the way in which he rejects the “reality” attributed to the real world.18 One will against another: the delirious person’s unshakeable conviction versus the psychiatrist’s resolute certitude.

Dick wasn’t mad, of course, but he felt himself to be sufficiently threatened by madness that he tried to have himself committed several times. In addition to periods of depression, he experienced violent psychotic episodes, accompanied by periods of delirium, to which the feverish composition of The Exegesis attests. Starting in the 1970s, Dick begins to be confronted with delirious and hallucinatory episodes of a religious kind. He goes through a succession of experiences that greatly resemble the experiences he will put his characters through: his world’s reality dissipates, allowing another world to appear … Instead of being in California in 1974, he was “absolutely convinced that [he] was living in Rome, sometime after Christ appeared but before Christianity became legal. Back in the furtive Fish Sign days. Secret baptism and that stuff.”19 There is no longer anything real about California; it has become a stage set, maybe even a hologram of the Roman Empire. Maybe our reality is only ever the product of a delirium, subjected as we are to deceptive appearances that conceal the true reality from us, as the Gnostics believed? Maybe we have false memories that will vanish when the resurrection of ancient times, the age of the first Christians, takes place? Are the United States of today no more than a resumption or perpetuation of the Roman Empire of yesteryear? Maybe Nixon’s downfall is even a manifestation of the Holy Spirit?20 A strange eschatology that makes the immemorial past return in the present on the basis of an anamnesis that grows more and more profound, more and more delirious—as was sometimes proposed in the philosophy of the Greeks. It isn’t so easy to free oneself from the idea of the resurrection.

Dick is convinced of being locked in a struggle with transcendent beings—extraterrestrials or gods—that have the power to falsify the real, to distort appearances, and to act directly on our brains. It is Descartes’s evil genius become SF character, the man of good sense against the master of illusions. We aren’t surprised to learn, then, that the main character of the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is named Rick Deckard and that he lives in a world populated with machine-animals.

Maybe Dick had to confront religion because it was one of the first means of creating other worlds, of populating them with extraterrestrial creatures (angels, seraphim, demons), and of inventing hitherto unknown modes of temporality and corporeal metamorphoses (immaculate conception, transubstantiation). Had he wanted to republish the Old and New Testaments, there was an SF editor who already had new titles lined up for them: the Old Testament would be called The Master of Chaos and the New Testament, The Thing with Three Souls.21 The whole question is knowing which type of fiction ultimately wins out in Dick’s work. Is science fiction placed at the service of his religious deliria, or does he succeed in incorporating the latter into science fiction? The situation is as follows: on the one hand, a succession of delirious episodes that keep him from having a psychotic break but that also disrupt the “field of reality”; on the other hand, reality is shot through with all sorts of deliria—economic, political, bureaucratic, and so on—and “deformed” by them. Dick’s stories are like a succession of scenes depicting the battle he wages against his own madness. This is particularly apparent after the series of religious experiences he undergoes between February and March 1974, when, in Radio Free Albemuth and VALIS, he depicts himself through two distinct characters: one who has just experienced psychotic episodes in the form of religious deliria, and another, an SF author, who is concerned about the mental health of the first. Here, we reencounter the confrontation between the madman and the psychiatrist, though we don’t always know which character takes on which of these roles. And this same struggle—between delirious possibilities and the prevailing reality—is found everywhere in Dick’s work.

The struggle is as much a war of the worlds as it is a war of the psyches. There is no psyche whose consistency would not be disturbed by the intrusion of another psyche. There is no world whose reality would not be altered by the interferences of another world. Because, for Dick, the plurality of worlds doesn’t mean parallel worlds “arranged like so many suits hanging in some enormous closet”;22 they never stop interfering with and impinging on one another, each world contesting the reality of all the others. The war of the worlds is at the same time a fight against madness. If several worlds exist, the question of knowing which of them is real necessarily arises. Once again, the question “what is reality?” is not an abstract inquiry but instead bears witness to the presence of an underlying madness. The madness pierces through the war of the worlds; it makes his characters crack, it distorts objects, makes machines go haywire, and destroys worlds.

Does that mean that Dick takes the side of madness, that he fights for the powers of delirium against all the forms of prevailing reality? That would be the function of his “delirious possibilities”: to contest the legitimacy of that reality, to denounce its falsity, arbitrariness, and artifice. Hence the many false worlds in Dick’s novels. Or maybe he takes the side of the doctor and tries to show the extent to which the prevailing reality itself is enclosed within multiple deliria—bureaucratic, economic, political—which all claim to be the one reality, excluding any alternative (VALIS)? We clearly aren’t dealing with an asylum doctor anymore, but it is nevertheless always a question of mental health—if only, as in Clans of the Alphane Moon, to prevent the earth from becoming a madhouse.

Lapoujade refers to “SF” without ever spelling out either la science-fiction or la fiction spéculative. While Dick is often thought of as a classic “sci-fi” author, his work, as Lapoujade shows, often challenges and exceeds any traditional conception of the genre. I have chosen to retain “SF” throughout to leave open the possibility of reading it either as science fiction or, more generally, as speculative fiction.—Trans.

Kingsley Amis, New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (Harcourt, Brace, 1960), 126ff.

It is generally thought that the term “science fiction,” in the sense in which we understand it today, began to spread in the 1930s, at the time when pulp novels were first beginning to appear.

Aristotle, Topics, A, 5, 101a–102b.

More recently, one could look to the logicist philosophical theories regarding possible worlds, from Saul Kripke up to the modal realism of David Lewis, which borrow many examples from science fiction. On the history of the notion of “possible worlds,” see Jacob Schmutz’s article “Qui a inventé les mondes possibles?,” Cahiers de philosophie de l’université de Caen, no. 42 (2005). For a literary exploration of the theory of these possible worlds, see La Théorie littéraire des mondes possibles, ed. Françoise Lavocat (CNRS Editions, 2010).

Philip K. Dick, “How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later,” in The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick, ed. Lawrence Sutin (Pantheon, 1995), 262.

Philip K. Dick, “Adjustment Team,” S2, 332. (All references to Dick’s stories cite the five-volume Complete Stories, published by Subterranean Press between 2010 and 2014. The volumes are cited in the notes as S1–S5, respectively.—Trans.)

Philip K. Dick, Time Out of Joint (Vintage Books, 2002), 156.

In the introduction to his Philosophy through the Looking Glass, Jean-Jacques Lecercle offers four arguments in favor of the untranslatability of the French term “délire” and subsequently leaves it (and its related forms, “délirer” and “délirant”) untranslated throughout the book. Despite the validity of Lecercle’s arguments and their applicability to the present study (we might say that Lapoujade’s “versions of Philip K. Dick” situate him within the “suppressed tradition of délire”), I have opted to use “delirium” (and its related forms) throughout this book for the sake of its readability. I hope that in consistently using the English cognate, even where an alternative term (such as “delusion”) might have fit more seamlessly, I have retained sufficient reference to the significance of this concept. For readers interested in a fuller discussion of this issue, see Philosophy through the Looking Glass: Language, Nonsense, Desire (Routledge, 1985), 1–14.—Trans.

Dick, “How to Build a Universe,” 262: “So I ask, in my writing, What is real? Because unceasingly we are bombarded with pseudorealities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms. I do not distrust their motives; I distrust their power. They have a lot of it. And it is an astonishing power: that of creating whole universes, universes of the mind. I ought to know. I do the same thing.”

Philip K. Dick, Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb (Ace, 1965), 328.

Philip K. Dick, “Introduction to The Golden Man,” in Golden Man (Berkeley, 1980), 92. (Lapoujade cites the introduction to Gradhiva, no. 29 by Pierre Déléage and Emmanuel Grimaud, “Anomalie: Champ faible, niveau légumes,” which quotes these lines (12).—Trans.)

Philip K. Dick, “The Day Mr. Computer Fell Out of Its Tree,” S5, 380.

Philip K. Dick, “Holy Quarrel,” S5, 187–88. In “The Day Mr. Computer Fell Out of Its Tree,” a computer experiences psychotic episodes, because it “had absorbed too much freaked-out input” (S5, 380).

Louis A. Sass, The Paradoxes of Delusion: Wittgenstein, Schreber, and the Schizophrenic Mind (Cornell University Press, 1995), 21.

Michael Foucault, Psychiatric Power: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1973–1974, ed. Jacques Lagrange and Arnold I. Davidson, trans. Graham Burchell (Picador, 2008), 132: “The psychiatrist, as he will function in the space of asylum discipline, will no longer be the individual who considers what the mad person says from the standpoint of truth, but will switch resolutely, definitively, to the standpoint of reality … The psychiatrist is someone who … must ensure that reality has the supplement of power necessary for it to impose itself on madness and, conversely, he is someone who must remove from madness its power to avoid reality.”

Foucault, Psychiatric Power. (This phrase would be found on page 166, but the sentence has been omitted from the English translation. My translation.—Trans.)

Foucault, Psychiatric Power, 135.

Philip K. Dick, The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), 33.

See Dick’s letter to Ursula K. Le Guin, reproduced in The Exegesis (48): “The spirit when he arrived here looked around, saw Richard Nixon and those creatures, and was so wrath-filled that he never stopped writing letters to Washington until Nixon was out … You wouldn’t believe his animosity toward the tyrannies both here and in the USSR; he saw them as twin horns of the same evil entity—one vast worldwide state whose basic nature was clear to him as being one of slavery, a continuation of Rome itself.”

This is Terry Carr, editor of the “Ace Double” collection, which would publish two SF novels in a single volume, tête-bêche. See The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick, 66.

Philip K. Dick, “If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others,” in The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick, 234.