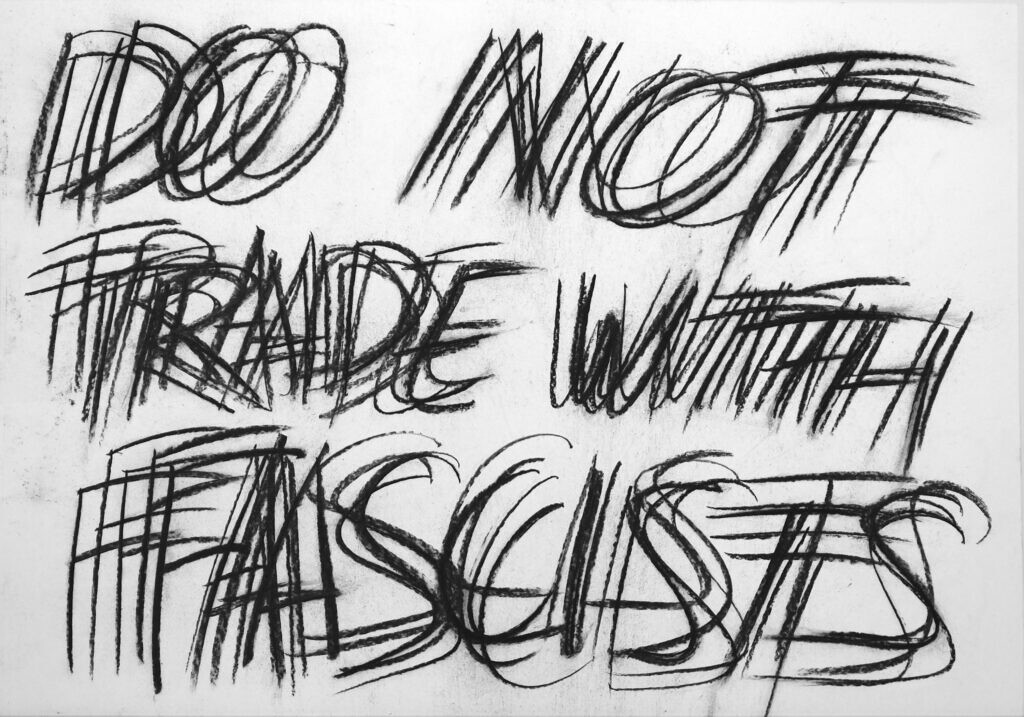

Nikita Kadan, from the series Repeating Text, 2024. Courtesy Transit gallery, Mechelen.

We can define the world’s current state as a “fascist moment.” It is not only a matter of the growing support for the far right in Europe and Latin America, the rise of Chinese authoritarianism, and the doings of the Putin regime as it pursues its criminal war in Ukraine. Fascization, as a complex combination of the rationale of state apparatuses, the dynamics of political movements, and popular psychology, represents the breakout of a tendency immanent to market-based society as a whole.

Fascism has not reemerged in the historical guise we know from the first half of the twentieth century. It has not been “reborn” because it is, by definition, devoid of historical continuity, and has never constituted a coherent ideological project. On the contrary, fascism thrives by aestheticizing history, by arbitrarily extracting narratives and images to suit the needs of the current political imaginary. Historicism, as an idea which envisions the world’s progress toward a better future, is all the more alien to it. Fascism does not stem from an obligatory or desirable state of affairs but from a real state of affairs, which is constantly replicated because human nature, rooted in ruthless struggle and the desire for domination, remains unchanged. As a century ago, today’s fascist moment totalizes these maxims of economic behavior, extending them to politics, society, and international relations. States and cultures, like individuals, are imagined as locked in a permanent conflict perpetually replicated over time.

According to the official Putinist narrative, Russia has thus been confronting the aggressive West for centuries, and “Russia’s great culture” has been one of the key weapons in this struggle. Ukraine, in this conception, has no independent essence; it is an artificial project, an “anti-Russia” whose only raison d’être is to act as “the West’s battering ram” in its project of destroying Russia. There is nothing new about this story, and every event only reprises the hoary archetype. Time loops in an “eternal return” in which individual and collective agency is nullified, thus asserting destiny’s absolute power over human beings.

The Second World War Didn’t Happen?

This temporal regime maps the “disappearance of a sense of history” in postmodern “late capitalism” which Fredric Jameson once described. Analyzing the workings of popular culture, he shows that its consumption, rooted in the severing of all connections among images extracted from different contexts and eras, resembles a schizophrenic’s sensibility. “Our entire contemporary social system,” Jameson wrote, “has little by little begun to lose its capacity to retain its own past, has begun to live in a perpetual present and in a perpetual change that obliterates traditions of the kind which all earlier social formations have had in one way or another to preserve.”1 Jameson’s conclusion was prompted by the situation in the early 1990s, when the universal dissemination of neoliberalism’s unconstrained market principles was echoed by claims about the “end of history.” In today’s geopolitical “struggle of civilizations,” each with its own unchanging “essence,” we are witnessing the true end of history as an idea of emergence in which nothing is perennial and there is always another future on the horizon to redefine and dismantle the existing order of things. In this sense, the two competing explanations of the world after the fall of the Berlin Wall—Fukuyama’s and Huntington’s—have been synthesized, and the end product is the end of history as an endless clash of civilizations.

This absence of history functions by displacing from the collective memory events that had fundamentally divided time into a “before” and an “after,” events in whose wake the world, its notions and values, could no longer be the same. The current fascist moment has put paid to two such events which had previously defined the historical meaning of the twentieth century: the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Second World War. While the first event reminded us that the oppressed can radically alter their circumstances and their “destiny” on their own, the second event told us that we should never repeat the monstrous experience of global war.

The effort to make sense of the Second World War generated the entire set of moral ideas and international institutions on which, all reservations aside, the contemporary world, or, more precisely, our sense of “normality,” was until recently built. Even radical critiques of this order of things invoked a set of concepts which drew on the lessons taught by the event: the unconditional condemnation of military aggression, universal human rights, and the inadmissibility of all forms of racism. This critique was grounded in “normality” since it revealed the inconsistencies between realpolitik and the world order’s generally accepted norms. The West’s military interventions in Afghanistan or Iraq, which were in fact acts of aggression, were camouflaged with “humanitarian” declarations, or explained away as acts of self-defense. They were (to borrow Hannah Arendt’s expression) “old-fashioned moral crimes,” or simple hypocrisy, which did not seek to establish new norms but played fast and loose with the old ones.2

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine effected a genuine break with normality by rejecting this vocabulary of familiar concepts. Without positing a new universal language, Putin’s Russia has proposed something more serious—making absolute relativism the new norm by constantly redefining concepts from a position of strength. The concept of a “multipolar world,” championed by the Kremlin, is based on the notion that moral and historical arguments are not grounded in a common language but are reducible to mere attributes of a particular state’s power. “The disappearance of a sense of history,” mentioned above, is expressed in a play on de-historicized images no longer in terms of popular culture, but as part and parcel of state ideology. For example, official Russian propaganda actually dubs all its enemies, foreign and domestic, “fascists,” while “anti-fascism” is declared a part of the distinct Russian identity. Moreover, Putin’s ideological narrative portrays the invasion of Ukraine as a replay of the Second World War, with Russian “anti-fascists” confronting a “fascist” West. The memory of a war that should never be repeated is thus turned into its opposite: we remember the heroic deeds of that war in order to repeat them over and over again. “1941–1945: we can do it again” is the succinct wording on the patriotic stickers which in recent years millions of Russians have pasted on their cars during the annual May 9 Victory Day celebrations.

A Process without a Subject

“Fascism” and “anti-fascism” have thus become synonymous with the duo “friend” and “enemy,” which, in keeping with Carl Schmitt’s notorious definition, form the basis of politics. For Schmitt, this notion of politics meant that moral and legal concepts had no independent regulative meaning and were constantly redefined through conflict. The true source of law—the decision-making sovereign—punches through the empty husk of norms, Schmitt argued. This enabled Schmitt to justify Hitler’s 1934 massive extrajudicial liquidation of his political opponents, known as the Night of the Long Knives. By transcending the rule of law, Schmitt argued, we can arrive at a political answer (who should decide the matter), rather than a moral answer (how the matter should be decided).

In today’s fascist moment, however, the sovereign does not make history but affirms his allegiance to the archetype. When justifying the necessity of launching the so-called special military operation in February 2022, Putin insisted that his hand had been forced. He had “no other choice”: he was only obeying fate, succumbing to the perennially rehashed showdown between Russia and the West, which figures as a kind of Althusserian “process without a subject.”

This paradoxical combination of voluntarism and fatalism reveals the profound link between contemporary fascism and neoliberal expediency. The neoliberal subject acknowledges the impossibility of altering the circumstances that dictate its will, but simultaneously it acts as a decider, constantly choosing the best behavior under conditions over which it has no power. Each of its particular decisions is thus a way of evading a genuine decision and recognizing the impossibility of achieving maximum arbitrariness, absolute “sovereignty.” Nonstop action is the market agent’s modus operandi: it must constantly react to circumstances and accept reality as a multitude of external challenges. Reality appears to it as something unknowable and chaotic, devoid of internal coherence and direction.

The capitalist individual’s efforts are rational vis-à-vis the irrational whole. Such irrationalism in private life is at odds with liberal democracy, which presupposes a kind of overall consensus about the rationality of everything that occurs. The complete loss of this horizon of reasonability—that is, of the notion (however vague) of a common interest and the progressive growth of a collective morality—extends fatalism to politics. Fascization means nothing less than the emergence of market individualism as the logic of the state.

The world has been turned into an arena of ruthless competition not only among different centers of power, but also among particularistic, homogeneous mindsets. In his multivolume work Noomakhia: Wars of the Mind, Alexander Dugin, the Putinist state’s most flamboyant and consistent ideologue, has hatched an entire theory of the “logos” of various civilizations. Each civilization, according to Dugin, has a unique archetypal mentality, its own worldview, which is ahistorical in nature, and unconsciously reproduced over the millennia. For example, there is, he alleges, a direct link between the rituals of the Celtic Druids and Lacanian psychoanalysis due to the existence of a “French logos.” Chinese foreign policy and the peculiarities of the political regime in India also heed the particular mindsets of their civilizations, whose main features are immutable. Consciousness is neither universal in nature nor in a state of becoming; rather, it constantly repeats the same moves within its particular civilization. Dugin fancies himself a Platonist, yet his Platonism boils down to the claim that ideas are eternal and immovable—although they do not have the quality of absolute truth, because the Russian “truth” never overlaps with the Japanese or the Arabic truth, for example. The supreme spiritual values, which the state enjoins its citizens to adopt, mean obeying collective destiny without questioning.

Thus, in early 2023, the Russian government announced the launch of “Russia’s DNA,” a large-scale program of school and university courses. Tellingly, “DNA” in this case stands for “spiritual and moral culture” (in Russian, dukhovno-nravstennaia kul’tura or DNK, which is the Russian acronym for DNA), thus directly equating biology with culture. One of the main courses, “Fundamentals of Russian Statehood,” which is compulsory in all tertiary institutions, tasks itself with “bridging the gap between a person’s actual identity and the realization of that identity.” Unconscious affiliation, as expressed in language and behavioral norms, should become a conscious matter, thus taking on the quality of a holistic system. This memory of obligation continues to be present biologically, as it were, but has temporarily been displaced from the minds of most young people, who are still under the influence of a hostile Western culture. With a little coercion from the state, their cultural “DNA” is activated, and they find themselves by recalling their predestination.

Culture is conceived here as an innate property tasked with defending the nation as a unified body, with fortifying it in the face of competition from other cultures (which are practically different biological species). Such fidelity to biology, which harmonizes the corporal and the mental, is simultaneously the best investment in oneself. As the course syllabus argues, a nation is “human capital,” constantly growing as it “realizes its identity.” Tellingly, the tendency toward the self-growth of capital in this approach corresponds to a fixed state of consciousness identical to its civilizational archetype.

This is an extreme instance of what Lukács defined as the “reification of consciousness”—that is, the adoption by consciousness of the commodity form, the transformation of the individual into a commodity among other commodities. “Human capital” (a concept borrowed directly from neoliberal jargon) refers to the supreme reduction of the human being to the commodity form’s abstraction. Individuals, who have an identical mindset which is equated with their biological unity (which was identified as racial unity in the previous Hitlerian version of fascism), are transformed into the capital possessed by the state qua civilization. The state thus becomes a form of capital, its direct expression. Fascism involves overcoming and destroying the political institutions and civil rights which mediate the relationship between the individual and the state and prevent the unlimited disposition of people as capital.

Fascism Between the Abstract and the Concrete

Fascism as the power of abstraction is paradoxically not at odds with fascist contempt for “abstract” human rights and international law. Even early nineteenth-century conservatives criticized the Enlightenment and the French Revolution as a triumph of abstract principles derived from pure reason that were not based on historical experience. As Joseph de Maistre wrote, “In my lifetime I have seen Frenchmen, Italians, Russians, etc. … But as for man, I declare that I have never in my life met him.”3 The abstract man created by the Enlightenment is devoid of the original form passed down from ancestors and inherited in cultural and state traditions (i.e., the “cultural code,” as Russian propaganda defines it nowadays). This person has inalienable rights, since it belongs to humanity as a single community, and therefore affirms universalism as a principle. At the same time, the universal recognition of the individual gives it freedom of choice, including its own identity.

Fascist racism is directed against those who stand as embodied abstractions, who rebel against traditional forms. Secularized Jews, with their passion for universalist ideas, or Slavs, as agents of anti-state Bolshevism,4 have symbolized this formlessness at various times among fascists. As they saw it, the forces of chaos were concentrated in their primary foe, the organized working class, with its allegiance to the ideas of social equality and international solidarity. Fear of the shapeless, animated by fleeting emotions and the rootless masses, has generally played a key role in all fascist movements.5 The revival of caste hierarchy, in which everyone knows their place and heeds their natural destiny, remains in one form or another fascism’s primary project, its image of the desired future.

In their propaganda, today’s ultra-rightists have predominantly replaced “abstract man” with Muslims, as disenfranchised migrants, or alleged adherents to a global caliphate, as well as with LGBT and trans people, who freely redefine their gender. In Putin’s Russia, which acts as the vanguard of the global fascist moment, any public expression of LGBT identity is a criminal offense and gender reassignment is completely prohibited. Russians must be specific in their affiliations, and their place in life by fact of birth must be firmly established in the hierarchy of social forms. The state, in keeping with Putin’s apt slogan, is the apex of this patriarchal hierarchy, a “family of families” united under the paternal authority of the nation’s leader. The “collective West,” as the bearer of universalist liberalism, with its principles of human rights and freedom of individual choice, has been proclaimed Russia’s principal foe. The object of hatred is “global liberal elites” who destroy “traditional values”—first of all, of the West itself. Over the heads of these hidden elites, with their secret plans of creating a “mechanical man,”6 liberated from its true natural essence, Putin’s Russia stands in solidarity with all the conservative forces of the Western world. The Kremlin’s support for Trump and Le Pen is thus not opportunistic, but ideological and programmatic.

As rooted in the Russian reactionary tradition, criticism of the West was paradoxically combined with Western centrism. As in the nineteenth century, the collective West in today’s Russian political imaginary is the only real entity from which imperial Russia demands recognition as an equal. Putin’s “anti-colonial” rhetoric and publicly stated “pivot to the East” should not fool us: they are merely the tools of pressure Russia needs to eventually take its rightful place among the dominant European nations. To achieve this goal, Russia must return the West to its true spiritual foundations and force it to recollect its own traditions. More recently, amid the ongoing war in Ukraine, Vladislav Surkov, one of the Kremlin’s ideologues, published a provocative article in which he predicted the future creation of a “Great North,” an equal triune alliance of Russia, the United States, and Europe that would dominate the world.7 The road to this alliance would be long, Surkov argued, but it was inevitable due to the common messianic Roman legacy of its members.

Empire and Imperialism

The notion that empire is Russia’s “destiny,” the only possible form of its existence, has been one of the key tenets of Putin’s official ideology. In the Russian conservative paradigm (most vividly mapped in the nineteenth century by Konstantin Leontiev), the imperial form was defined as existing outside of time: unlike modern nation-states, the empire does not strive for perfection and equality, but instead keeps the “blossoming multitude” of endless class and cultural differences from being swallowed up by history. The burden of empire, Leontiev argued, was to resist progress and preserve an equilibrium of differences that is timeless. This immobility of empire as a form, however, has always created a need for the constant mobilization of its borders. To remain unchanging, the empire must constantly push outward, expanding its territory. It is this permanent outward expansion, as Surkov wrote in an earlier article, that helps maintain political stability by “exporting chaos” and “accumulating new lands.”8

The archaic idea of empire in this interpretation jibes completely with imperialism, a phenomenon of the modern age and the capitalist system. Rosa Luxemburg argued that imperialism was predetermined by the very structure of capital accumulation, which constantly had to surpass its own limits and expropriate territories and economic patterns not yet plugged into the capitalist economy. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt developed this line of thought, arguing that imperialism was a direct precursor to European fascism. In Arendt’s view, imperialism replaced the political idea of the state as a community based on consensus with the economic rationale of continuous expansion. Imperialism did not involve expanding the boundaries of the political community; on the contrary, it established an impenetrable border between the metropole and the colonies. Political power, which had previously been tasked with preventing violence at home, instrumentalized uncontrolled violence beyond its borders. The identity of power and violence laid down by European imperialism then returned to the heart of Europe in the guise of deportations and death camps. The mass extermination and dehumanization of subjugated populations practiced by the colonizers was unleashed by the totalitarian state on the home front.

Imperialism thus both affirms the insurmountable borders between the foreign and the domestic and makes them movable and contingent. Russian imperialist expansion in Ukraine, beginning in 2014, was marked by the creation of fictitious “people’s republics” which were fully dependent on Moscow, but whose legal regimes were markedly different. Whereas Putinist Russia was, until 2022, an authoritarian regime which resorted only to targeted crackdowns, the violence of the armed groups affiliated with the local leaders in Donetsk and Luhansk was virtually unrestricted. Once the full-scale invasion of Ukraine commenced, the Russian regime’s transformation into a straightforward brutal dictatorship was largely embodied by the export of this culture of violence from the hinterlands to the imperial center.

The Fascist Moment as the Fullness of Contemporaneity

At the global level, Russia, as a semi-peripheral region, became neoliberal capitalism’s “weak link” and was the first to realize its latent tendency towards fascization. This tendency, combining the tension between inside and outside which I have described, is both an acceleration of neoliberal capitalism and a quasi-critique of it. The anti-Western ressentiment which is one of the main motifs of Putinist propaganda often includes a critique of “radical neoliberalism” in which the particular “collectivism” of the Russian people is contrasted with Western “individualism.”9 In a similar vein, European right-wing populists denounce “globalist elites” who are destroying the established lifeways of ordinary people. However, fascism in the first half of the twentieth century was even more radical: it directly attacked “plutocratic capitalism,” offering an alternative in the guise of a corporate “people’s community” that had surmounted class conflicts.

Today’s fascist moment has emerged from the neoliberal “perpetual present” and differs from classical fascism in its complete lack of a utopian horizon, however reactionary. Just as a century ago, however, fascism has been born out of capitalism’s non-synchronicity, the coexistence of different experiences of time within the same reality. As Ernst Bloch has shown, German Nazism was the means for intermediate social groups that did not fit into modernity, whose worldviews were seemingly “backward” vis-à-vis their own era, to enter the political arena.10 Nevertheless, this “backwardness” is not only a legitimate part of a complexly organized contemporaneity, but also proves capable of taking command of its internal, previously hidden tendencies.

In our day, the far right, with its calls to “bring back” the bygone harmony of the nation-state, is both a reaction to neoliberal capitalism’s contradictions and an expression of its mainstream. Our contingent “contemporaneity” manifests itself in its entirety insofar as it brings to light everything that was previously displaced, everything that was recently treated as archaic and a relic of the past.

Two decades ago, the liberal Western mainstream labeled the right-wing critique of globalization as a threat to national sovereignty, a powerless attempt to stop the advent of a future in which there would be no barriers to the free movement of goods and people. Today, we can state that neoliberal globalization has proved to be a necessary stage on the road to deglobalization and the extension of the logic of market competition to the level of states in a marvelous new “multipolar world.” Post-Soviet Russia, which was the testing ground for radical market reforms in the 1990s, then synthesized the ultimate neoliberal expediency and its reactionary anti-liberal ideology in the guise of a neofascist regime. This regime does not offer the world an alternative project or open the horizon to a shared, albeit frightening, future. On the contrary, it is entirely rooted in the present as an “endless horror show,” acting as the concentration of the world’s fascist moment.

Translated from the Russian by Thomas H. Campbell

This essay was commissioned by steirischer herbst ‘24

Fredric Jameson, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983–1998 (Verso, 1998), 20.

Hannah Arendt, “Some Questions of Moral Philosophy,” Social Research 61, no. 4 (1994), 743.

Joseph de Maistre, Considerations on France, trans. Richard A. Lebrun (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 53.

Carl Schmitt, Roman Catholicism and Political Form (Bloomsbury Academic, 1996).

Ishay Landa, Fascism and the Masses: The Revolt Against the Last Humans, 1848–1945 (Routledge, 2019).

See → (in Russian).

See → (in Russian).

See → (in Russian).

See → (in Russian).

Ernst Bloch, The Heritage of Our Times (Polity, 2009).