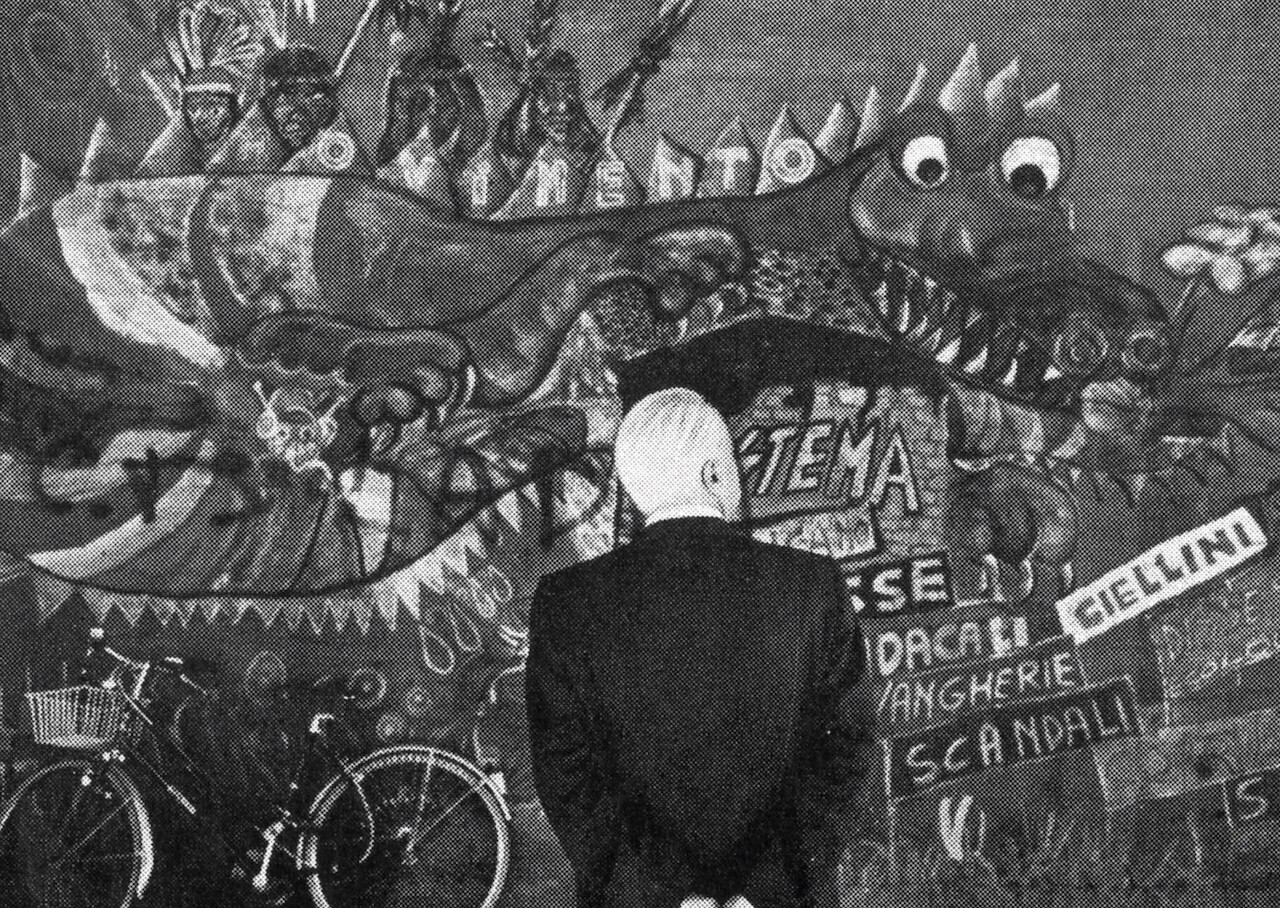

Man inspects the mural of the dragon of autonomy. Photo: Tano D’Amico (1977).

This essay is excerpted from A Thousand Little Machines: A/traverso and the Movement of ’77, the first book published by Agit Press. The book contains the recollections of the autonomist militant, philosopher, and media theorist Franco “Bifo” Berardi on autonomia and the tumultuous events of ’77, told through the pages of A/traverso, the Bolognese movement sheet he produced with others between 1975 and 1981.

***

When one speaks of 1977, a series of associative chains, images, memories, concepts, and words—often incoherent with one another—are set in motion.

’77 is the year in which movements of students and young proletarians explode and unfold across Italy, expressing themselves in a particularly intense form in the cities of Bologna and Rome. In some contexts, ’77 evokes an idea of violence and oppression. It is in the middle of the Years of Lead, of fear in the streets and in the schools. In other contexts it evokes creativity, the happy expression of social and cultural needs, mass self-organization coupled with innovative forms of communication.

How, then, can these two contradictory visions coexist, and often in the minds of the same people? To answer this, we need to re-situate 1977. 1977 is a junction, or better yet a point of caesura, the point at which two different eras meet each other (or, perhaps, separate from each other—although this is the same thing). It is a moment of the emergence and formation of two incompatible visions, of two dissonant perceptions of reality. In that year, the history of a century finally comes to maturity—the century of industrial capitalism and of workers’ struggle, the century of political responsibility, and the century of the great mass workers’ organizations.

’77 also heralds the postindustrial era, the microelectronic revolution, the network principle, the proliferation of horizontal communication technologies, and thus the dissolution of organized politics. The crisis of both the nation-state and the mass parties begins to dawn. We should not forget that besides ’77 being the year of creative protest movements in Italian universities and neighborhoods, it was also many other things, not always aligned in the same direction nor under the same sign.

It was the year of the emergence of punk rock, the year of the Queen’s Jubilee contested by the Sex Pistols, who turned the British capital upside down for days and days with music and barricades, launching the cry that would mark the next twenty years like a curse: NO FUTURE.

But it is also the year in which, in the garages of Silicon Valley, boys like Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs—emanating from the libertarian and psychedelic hippy counterculture—succeeded in creating user-friendly interfaces that would make ever wider, ever more popular access to information technology, and then to network telematics, possible a few years later.

It was the year in which Simon Nora and Alain Minc would write a report to the president of the French Republic, Valery Giscard D’Estaing, entitled L’informatisation de la société, in which they outlined the social, political, and urban-planning transformations that could be expected following the introduction of digital technologies and telematics (i.e., distant computing; i.e., computer networking; i.e., the internet) into work and communication.

’77 was also the year in which the rebels of the Gang of Four, Chang Ching, Wang Hung Wen, Yao Wen Juan, and Chang Chung Chao, were put on trial. The four ultra-Maoists from Shanghai were dragged in chains to Beijing and sentenced to long prison terms because they represented, in the eyes of the new Dengist ruling group, the utopia of an egalitarian society in which all economic rules are obliterated in favor of the absolute primacy of ideology. The communist utopia began its long crisis precisely at the point where it had been taken to its extreme, bloody consequences—precisely where the Proletarian Cultural Revolution had unleashed its most radical and intransigent tendencies.

But it is also the year in which the first actions of workers’ dissent spread in Prague and in Warsaw. It is the year in which Czechoslovakian dissidents signed Charter ’77.

It is the year in which Yuri Andropov, at that time the director of the KGB, wrote a letter to the walking corpse of Leonid Brezhnev, party secretary and highest authority of the Soviet Union, to tell him that if the USSR does not quickly catch up in the field of information technology, socialism was doomed to collapse.

So ’77 cannot be understood merely by leafing through the Italian photo albums of long-haired young men with their faces covered by balaclavas or scarves. It cannot be understood by merely listening to truculent slogans that are partly ideological and partly bizarrely surrealist.

In that year, the page of the twentieth century was turned, just as in 1870–71. In the bloody streets of Paris, the Commune had turned the page of the nineteenth century and shown with what light and with what shadows the twentieth century was announcing itself on the horizon.

Let us try to keep this complexity in mind when we speak of events belonging to the Italian autonomous and creative movement. Only from this complexity can we understand what actually happened beyond the chronicles of the squares, beyond the demonstrations and the clashes, beyond the Molotov cocktails, beyond the debate on violence, beyond the violent repression with which the state and the left attacked the movement to the point of criminalizing it and pushing it into the arms of brigatist terrorism.