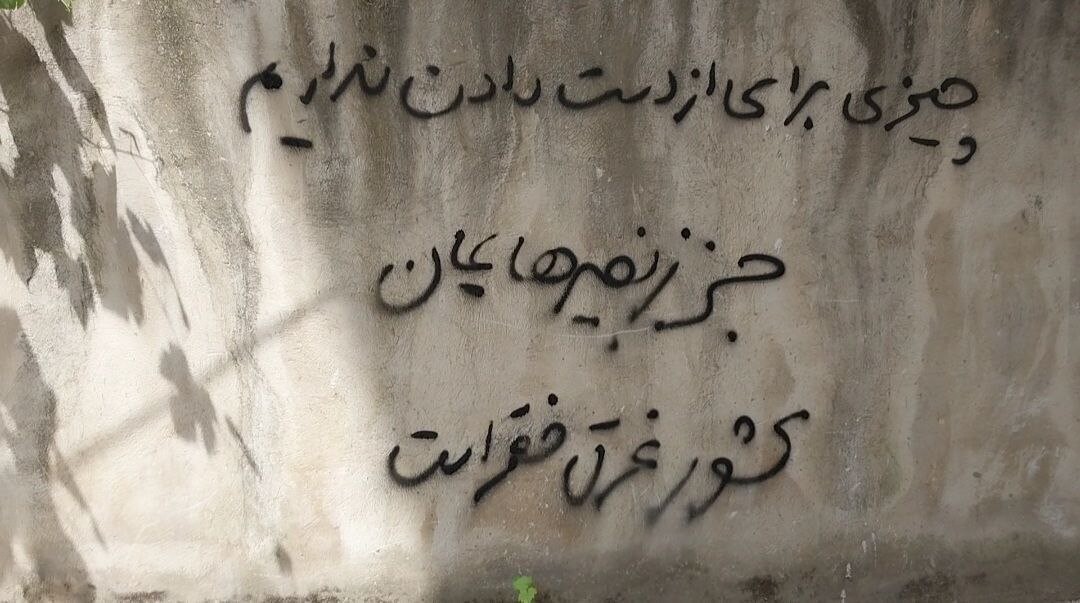

“We have nothing to lose but our chains. The country is drowning in poverty.” Rasht, Iran, May 2023. Source.

As the movement continues, there will come a time when the spirits of the masses will change. It is inevitable that their desires and interests will evolve, transforming spontaneous actions into conscious endeavors.

—Mohammad Mokhtari, “A Study of the Slogans of the 1979 Uprising”1

The Birth of A New Cycle of Struggle

The onset of the 2017–18 uprisings in Iran, which “represented a watershed moment in the history of the Islamic Republic, when millions of proletarians across the country in more than 100 cities rebelled against the ruling oligarchy, saying ‘enough is enough’ to a life governed by misery, precarity, dictatorship, Islamist autocracy, and authoritarian repression,” marked the beginning of a revolutionary period in the process of its realization—a process of realizing both the possibility of social transformation as well as attendant forms of collective subjectivity.2 That is to say, from 2017 through the Jina Revolution of 2022–23, Iran saw a new cycle of struggle characterized by nationwide rebellions whose size and militancy increased with each successive year.3

In spring 2018, Iran’s southwest province of Khuzestan saw mass demonstrations and protests by the region’s majority ethnic Arab population against a water shortage whose severity was rivaled only by the region’s air pollution and the Islamic Republic’s continued prohibition on cultural and linguistic practices proper to Khuzestan’s Arab communities. In the months that followed, workers at the Haft-Tappeh Sugar Cane Factory in Shush (4500 employees) and workers from the National Steel factories in Ahvaz (four thousand workers) went on strike—with steel workers organizing solidarity strikes with the workers at the Haft-Tappeh factory while chanting, “Death to this demagogic government.” Truck drivers also self-organized a series of coordinated strikes that spread to all thirty-one of Iran’s provinces by the end of the year. Of equal, if not greater, significance is the composition of the strikes carried out by workers from the Haft-Tappeh Sugar Cane Factory and National Steel during the first two weeks of November of the same year. More than a simple demonstration of fidelity to struggle in productive sectors that are key to the Iranian economy, these strikes were composed and sustained by the participation of family members of striking workers, mainly women and children. They thus involved the conjugation of reproductive and productive subject positions vis-à-vis the accumulation of value.

With each successive wave of protest and strike, and in tandem with struggles against economic immiseration, demands were increasingly issued by groups whose social existence has been subjected to the vicissitudes of privatization and corruption—e.g., university students, human rights activists, political prisoners, local shopkeepers, teachers, as well as the country’s marginalized ethnicities (Kurdish, Balochi, Arab, etc.). And of the various chants heard in the streets4 during 2017–18 uprisings, “Bread, Work, Freedom” is the slogan that retains the greatest significance despite the fact that its political content ultimately remained reformist (similar to demands for improved working conditions, increased wages, and the de-privatization of the Iranian economy).5 If the uprisings of 2017–18 can be characterized as a wave of national rebellion whose modalities of struggle were largely militant and based on practices of direct action, but whose political horizon remained within the purview of a struggle for the recognition of rights, the same cannot be said for the uprisings of 2019–20. In the latter, the Islamic Republic of Iran

encounter[ed] ever-increasing struggles and movements of workers, students, teachers, retirees, women, and ethnic and religious minorities. These two “levels” of struggle—the spontaneous mass uprising and the more organized forms of resistance—are mutually interrelated. The former has radicalized the latter, making it more political than before. For instance, the demands of some parts of the working class have moved away from the improvement of the conditions of work, wages, and de-privatization and towards the autonomous management of factories and radical alternatives.6

It should come as no surprise, then, that with this notable increase in the specific determination of freedom at the heart of the demands, the slogans from 2017–18 would modify themselves in turn. In contrast with the previous most popular slogan, “Bread, Work, Freedom,” in 2019–20 people took to the streets chanting, “Bread, Work, and Workers’ Councils” and “Bread, Work, and the Right to Wear Anything You Want.”7 And yet, as with every escalation of tactics on the part of protestors, a strategy of counterrevolutionary reaction followed in the shape of the 2020 February elections. Regarding the significance of the elections in light of the previous years of revolt, one comrade said:

Note that today, the so-called rivals in the previous presidential elections are the heads of the executive, judiciary, and legislative administrations. The February elections marked the ending point in this integration process—which does not mean that their internal conflict of interests is solved, of course. The heads of the three branches have already made extrajudicial decisions, one of which was the increase in petrol prices last November [2019] that resulted in an unprecedented national uprising and a bloodbath in which protesters were killed.8

In the year that followed (2020–21), Iran’s provinces of Khuzestan and Isfahan would return to the streets in mass demonstrations against a lack of access to water. There was also a series of strikes by project workers at key oil refineries, whose demands included several months of wages they had yet to receive, thus giving rise to the popular slogans of this period: “The prices are in dollars, our wages in rials”; “No to forced displacement” (کلا کلا للتهجیر); “No to humiliation” (هیهات من الذله). On the heels of this year of struggle waged against the processes of both production and circulation, in April 2023 Iran’s growing teachers movement took to the streets.9 Its demands pertained to both economic and extra-economic concerns, e.g., the right to teach specific curricula, the right to teach in languages other than Farsi, the ability to create adequate learning environments for students, and wages.

This annual wave of rebellion would culminate in the Jina Revolution after Iran’s “morality police” murdered Jina Amini while she was being held in police custody.10 To make matters worse, on September 30

security forces in Zahedan, the capital of Sistan and Baluchistan Province and home to the long-oppressed Baluchi minority, cracked down on protesters. Security forces killed at least 94 people, including children, and wounded at least 350 in turn. This incident, which marked the deadliest day since the beginning of the nationwide protests against the Islamic Republic, has been called “Bloody Friday.”11

During these early days of the Jina Revolution, when streets were filled with slogans announcing solidarity among Iran’s historically marginalized ethnic and social groups—“Zahedan, Kurdistan, the eye and light of Iran,” “Kurd and Baluch brothers, rise [up] and overthrow the mullahs,” “Rise up Baluch, your good days are coming,” and “Kurdistan is not alone, Baluchistan is its supporter”—what became clear was that the situation on the ground was one in which “the Islamic Republic [was] already dead in the minds of its people; now the people must kill it in reality.”12

Despite this all-too-brief survey of political “unrest,” what is clear is that 2017 marked the beginning of a two-fold dynamic of resistance and mobilization against the processes of both production and circulation and their attendant mediations by an Iranian state that is more frequently managed rather than governed under the auspice of its Islamic Republic. This dynamic is characterized by strikes in key productive sectors of the Iranian economy (largely undertaken by the most precarious and marginalized workers, such as project workers in Khuzestan’s oil industry and Baloch miners); a generalized practice of dis-identification with the social functions individuals have been compelled to assume, which reached its peak in the Jina Revolution (the teachers’ movement, self-organized national strikes by truck drivers, women’s removal and burning of their hijabs in protest against the laws surrounding its compulsory use, and so on); and the mass withdrawal of participation in the reproduction of the established order—a refusal of complicity with a regime whose commitment to future prosperity can only take the form of a false promise.

Put in the most general terms, ever since 2017 Iran has become an exemplary laboratory of what becomes possible when both production and circulation struggles13 are coextensive, simultaneous, and guided by a militant sensibility toward a shared practical problem: how to reproduce one’s social existence without reproducing the accumulation of value in the hands of the suicidal state of Iran.14 Those who have taken to the streets have effectuated the means of discerning the really existing possibility of revolution that currently inheres within this still ongoing cycle of struggle. They have discovered that to simply pose this question is already to inquire into what one intuits every day on the streets and grasps with the certainty of feeling that “it is only in an order of things in which there are no more classes and class antagonisms that social evolutions will cease to be political revolutions.” Until that time comes, “on the eve of every general reshuffling of society, the last word of social science will always be: struggle or death; bloody war or nothing. It is thus that the question is inevitably posed.”15

And so, even from this cursory survey of the modes of organization and struggle employed by different social groups over the six years of 2017–23, it is clear that this period marks a qualitative break with all prior cycles of struggle ever since the 1979 Revolution, for both those in Iran and in diaspora. What is more, this is a period whose historical and material reality serves as the basis upon which revolutionary theory can orient itself in the direction of historical and nascent forms of struggle and organization, allowing for (i) the collective articulation of a set of theoretical commitments and relations of solidarity across social differences; and (ii) the collective practice of theoretically grasping the salient determinants constitutive of the structuring dynamics of this cycle of struggle. Especially during the Jina Revolution, collective modalities of antagonism in Iran grew increasingly uncompromising in their refusal, announcing themselves through a series of slogans that have since become household phrases the world over: “Bread, Work, Freedom,” “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (Woman, Life, Freedom). Conversely, when seen from the vantage point of the Islamic Republic, slogans such as these indicate a really existing material threat to the very reproduction of the Iranian state—precisely because one of the ongoing concerns of the regime has been securing the “smooth” transition to the next supreme leader. As one comrade put it in the wake of the February 2020 parliamentary elections:

The unified conservative parliament is one of the pieces of the puzzle in the “transition period,” referring to the selection of the next Supreme Leader. And the puzzle is a unified conservative government, homogeneous enough to ensure that the transition to the new Supreme Leader goes smoothly. The parliament, all the institutions of the so-called “republic,” and its representation apparatus are all defunct. The crisis in the Islamic Republic is no longer about “legitimacy”—it is a crisis at the roots of governmentality itself.16

For both the protestors in the streets and the regime’s functionaries in the halls of parliament, the current conjuncture is one of “transition” such that the present, once more, becomes the temporal modality of the struggle to determine the shape of Iranian politics to come. It is to the credit of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) that is has openly confirmed the public secret at the heart of its historic mission of statecraft: to be governed by the IRI is to be subject to a regime that can neither govern without the looming specter of civil war nor maintain any pretension to being a good-faith interlocutor. It is to be subject to biopolitical management by the guardians and owners of repressive force. If there is anything governmental regarding the IRI it is the banal, but no less barbarous, fact that it is the government of the living by the (politically) dead.17

In the wake of Iran’s previous period of mass political mobilization in response to the stolen elections of 2009, the Supreme Council appointed bureaucrats and functionaries who are known allies of Khamenei. The regime brutally repressed the Jina Revolution and continues to executed prisoners regardless of political affiliation. Iran is currently living through an Islamic Republic that is constituting itself into a political force “that appropriates the state and channels into it a flow of absolute war where the only outcome is the suicide of the state itself.”18

The Logic of Revolution in Popular Form

Against this historical backdrop, the cardinal virtue of Shirin Mohammad’s Rebellion of the Slogans (2023) is its successful articulation of the following thesis: 2017–23 is a period defined by the decomposition and recomposition of popular rebellions and state-sponsored immiseration, marking the emergence of a new cycle of struggle in Iran.19 It is a period of struggle narrated via the transformation of the 2017 slogan “Bread, Work, Freedom” into the 2019–20 chant “Bread, Work, and the Right to Wear Anything You Want,” and then into the watchword, or “symbol,”20 of the eponymously named Jina Revolution and its attendant slogan now known across the globe: “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi.” Neither exhibition nor archive, Rebellion is perhaps best understood as a kind of “prolegomena” on the present and future of Iran’s current cycle of struggle.

Following from, and inspired by, Mohammad Mokhtari’s seminal taxonomy of political slogans in the wake of the 1979 Revolution, and by virtue of documenting slogans from the past six years of a nation in revolt—organized, translated, and presented in a limited-run publication—Rebellion allows us to grasp the possibility of revolution in its most palpable manner: whether in the form of graffiti or protest chants, each slogan is indexed to a generalized refusal and a qualitative transformation in the political sensibilities of various forms of social protagonism. However, unlike Mokhtari’s work of classification and its aim of reconstructing the relationship between slogan and the subject of which it is the utterance, Rebellion maintains the anonymity of the authors/speakers.21 The decision to proceed in this manner, however, is not primarily based on formal, curatorial, or aesthetic commitments. By retaining the anonymity of its subjects, Rebellion asserts that the political significance of a given slogan is not to be found in the character of its author, but by virtue of its circulation in public space. Public slogans make a series of political (dis)positions readily visible, which may then be assumed by anyone who recognizes something of themselves in a bit of paint on a wall or a simple turn of phrase. For Rebellion, the fact that slogans “make movement,” to borrow a phrase from Verónica Gago, is of decisive importance. As Gago writes:

Capable of finding, for moments, common vectors of meaning, effectively bringing together the movement’s action and, at the same time, understanding that this terrain on which we fight consists of the multiplication of dissimilar situations, of diverse landings … the slogans that make movement (here I am reformulating the idea of the Chilean feminist Julieta Kirckwood … who speaks of questions that made a movement) is a decisive point. Slogans have a spatial and temporal validity, but their force lies precisely in connecting bodies and statements. When we read slogans that make sense across borders, they indicate dates (in which those words express a moment) and bring together theses that organize a way of understanding what happens and even orienting it … In all of them we find a set of unique elements that express very specific conjunctures that, at the same time, are able to be almost immediately translated into others. They express, without a doubt, incorporeal transformations that are translated into ways of experiencing violence, self-defense, insecurity, collective force, the dispute over everything that makes up the perseverance of living in increasingly urgent contexts. These slogans imply transformations in bodies, they materialize thresholds in links, they propose a collective horizon. And they do not lose their relationship with that common plane of the reproduction of life.22

As with any period defined by uncompromising insurrectionary fervor, to study the slogans of a given cycle of struggle is to study the extent to which its modes of collective antagonism encourage or restrain militant refusal and the very possibility of revolution. Anonymously authored, slogans register what has become a really existing, practical, political position that one can assume vis-à-vis the Iranian state. To study revolutionary slogans, or slogans originating from a period of intense insurrectionary revolt, is, therefore, to investigate the modalities of collective action made possible in moments when a real material rupture is effectuated by a collective political subject in the process of its realization:

Tracts, posters, bulletins, words of the streets, infinite words—it is not through a concern for effectiveness that they become imperative. Effective or not, they belong to the decision of the instant. They appear, and they disappear. They do not say everything; on the contrary, they ruin everything; they are outside of everything. They act and reflect fragmentarily. They do not leave a trace: trait without trace. Like words on the wall, they are written in insecurity, received under threat; they carry the danger themselves and then pass with the passerby who transmits, loses, or forgets them.23

Put differently, to study revolutionary slogans is to embark on a study of the possible since “the only mode of presence of revolution is its real possibility.”24

As with every moment of upheaval where the character of the revolution has yet to be determined, the Jina Revolution tempts historical comparison:

In the immediate aftermath of the [Islamic] Revolution, on March 8, 1979, tens of thousands of women marched in the streets of Tehran against the imposition of compulsory Hijab, chanting “Neither headscarf nor beatings for wearing it” (نه روسری نه نه توسری) and “We did not make a revolution to go back”—referring to the reactionary aspect of compulsory Hijab that aims to “turn back” the wheels of history. At the time, the Islamist media and Khomeini labeled the feminists and other women on the streets as supporters of imperialism who subscribed to “Western culture.” Tragically, no one heard the women’s voices or heeded their warnings, not even the leftists who—catastrophically—accorded an ontological priority to the struggle against imperialism, relativizing and downplaying all other forms of domination as “secondary.” Today, when women burn scarves on the streets and the whole society emphatically rejects compulsory Hijab, this shakes the entire patriarchal and autocratic authority to the core, along with the pseudo-anti-imperialist legitimacy of the Islamic Republic.25

Less than two years after the Jina Revolution, we appear to have entered a period comprised of “the most motley mixture of crying contradictions,” as Marx wrote in “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.”

But the twenty-fifth of Shahrivar was no eighteenth Brumaire. It is only with the former that a new cycle of struggle was realized as an actual, concrete, really existing social phenomena whose first law was absolute refusal. It inaugurated a period of wild agitation—not in the name of civil peace but against the tranquility on whose behalf every reactionary campaign is waged—with truth alloyed to passion. It was replete with heroic deeds without the need for heroes, and historical-collective subject formations in the process of writing their own histories. These subject formations were first to declare, “We are still not living through the coronation of Pahlavi the younger.” As for collective will, it was found in those moments where both protestors and events no longer appeared as shadows divorced from their bodies: this revolution does not paralyze its own bearers, for it is that by which revolutionaries are made. Perhaps it was L who put it best, offering her readers one of the first encapsulations of the Jina Revolutions: “See this body, observe the entirety of this history.”26 It became easy to spot these bodies in the midst of their becoming-revolutionary by virtue of a shared, identifying characteristic: mobilizing in public with a certainty of purpose absent any guarantee of the revolution’s successful outcome.

By now, it would be redundant to emphasize the exigency of breaking with the past, for this was felt by every person who took to the streets regardless of the peaceful or militant nature of their protest. However, for the IRI, the threat of Iranians breaking with the past has by now assumed so many forms that its possibility appears even in conventional acts of ritual and tradition: a procession of funeral-goers “dressed in dark clothes,” whose hope for emancipation now lies in a liberated Kurdistan, looks to the regime like an “army of undertakers,” “revolutionary undertakers.”27 In this night where all mourners are dressed in black, the really existing possibility of revolution no longer appears in the red “Phrygian caps of anarchy” or the “White” of Shah Pahlavi’s (counter)revolution, but in the thawb ḥaddād of Kurdish pallbearers.28 Beginning with the Jina Revolution, this new cycle of struggle pronounces its judgment on the IRI. The slogans of this uprising assert their own critical theory of Iranian society, showing the rebellion’s logic in popular form.29

Counter-Memories Against the State

In light of the propaedeutic function of Rebellion of the Slogans, two responses to the work are worth noting. Each, in its own way, engages with the central methodological question that guides the work: Is it possible to narrate history via slogans? If so, what form must such narratives take to avoid both left melancholia and the demobilizing affect of ressentiment? In her 2023 lecture at Künstlerhaus Bremen, “From Khavaran to Evin: Politics of Memory and the Slogans of the Jina Revolution,” Yasmine Ansari proposed that the slogans of 2017–23 constructed an archive of the history of the rebellion, itself continuously threatened with erasure. Under the IRI, erasure is made permanent precisely because the conditions for historical remembrance are replaced by the institutional compulsion toward the memorization of an “official history,” whose function is the continued legitimation of the IRI. As Ansari put it, “Mnemonic manipulation is a defining characteristic of the Islamic Republic’s politics of memory.”30 Rebellion of the Slogans finds in revolutionary slogans, as collective expressions of a life beyond economic and extra-economic domination, the very history that the IRI seeks to liquidate. When protestors chant, “Forty years of crime, death to this leadership,” it is a rejection of the IRI’s politics of denial and enforced amnesia: the slogans of the Jina Revolution are themselves “counter-memories” against the state. The narration of history via slogans becomes the narration of the tradition of all those oppressed by the Islamic Republic.

Mahdis Mohammadi asks whether the relationship between historical narration and slogans can be similarly approached via images. In her own lecture responding to Rebellion of the Slogan, she wondered if images, particularly images of resistance that repeat over time, could serve as a foundation for narrating the history of the oppressed.31 Surveying images and videos of women removing their hijabs in public to protest against the IRI, Mohammadi noted the emergence of a collective figure specific to this cycle of struggle. With the Jina Revolution, each iteration of a woman taking off her hijab in public belonged to a long history of the desire for liberation proper to the history of feminism in Iran. Thus, the systematic erasure of counter-memories of rebellion, whether as images or slogans, is central to the IRI’s project of establishing and reinforcing a triumphalist narrative regarding the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Kurdistan: The Graveyard of Fascists!

In December 1978, soon-to-be supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini wrote a letter to the head of Iran’s provisional government, Mehdi Bazargan. The letter charged Bazargan with establishing an “Oil Strikes Coordinating Committee,” since “Khomeini was worried the Shah would use the fuel shortage to legitimize the crackdown on the revolutionary movement.”32 In the first weeks of January 1979, the committee released its first communique, announcing that it had become

necessary to bring to the attention of the defiant nation of Iran that the blue-collar and white-collar workers responsible for effecting the Imam’s directives, are pious strikers who are working in the production units and the refineries for the welfare of the defiant nation and have no intention to gain anything for themselves.33

More than forty years later, striking oil workers no longer laid claim to the virtue of piety. Instead, they openly espoused the revolutionary content of their impious strike against the Islamic Republic. When oil workers organized a solidarity strike to protest the regime’s brutalization of students across the country, one heard not pious chants but rather slogans such as “This is the year of blood.” What could be more impious than demanding the blood of the Supreme Leader?

If, in 1979, funerals were a site where Khomeini and his supporters co-opted the revolution, today the IRI no longer finds would-be supporters in funeral processions, which transformed into sites of protest during the Jina Revolution. And if, in 1979, the slogans of striking oil workers “began to merge with those of Islamists”—an alliance that proved crucial to overthrowing the US-backed monarchy of Reza Shah Pahlavi34—today it has become common to hear funeral-goers chant a rather different revolutionary slogan: “Kurdistan is the graveyard of fascists.”35

Published in Ketab-e Jom’e (کتاب جمعه) Magazine, no. 20/24 (December–February 1980).

Collective 98, “On the Anniversary of the 2019 November Uprising in Iran,” collective98.blogspot.com, December 7, 2020 →.

Other slogans from this period that are worth noting: “Reformist, principlist, your time is up,” “Don’t be afraid, don’t be afraid, we are all together,” “Death to Rouhani,” “Death to Khamenei,” “Death to the dictator,” and “This is the final word: the only target is the regime.”

I use “reformist” here not as a pejorative or implicit criticism of the modes of struggle chosen by those on the ground. Rather, it underscores how protestors viewed such demands as a viable avenue for transforming their material conditions, even as the dynamic that structured the relation of the Iranian government to protestors was left unchallenged, except through abstract slogans.

Collective 98, “On the Anniversary of the 2019 November Uprising.”

Several other slogans from this period are also significant insofar as they register the degree of the polarization of the possible political positions one may assume with respect to Iranian society: “Be afraid, be afraid, we are all together,” “We want neither Shah nor the Pasdar, death to these two hyenas,” and “Capitalist mullahs, give us back our money.”

CrimethInc., “Iran: ‘There Is an Infinite Amount of Hope … But Not For Us,’” crimethinc.com, October 8, 2020 →. Emphasis added.

“When we talk about the ‘teachers’ movement,’ we do not only refer to the political-trade union activity of officially employed teachers. This movement also includes charter and contract teachers, preschool teachers, teaching assistants of the literacy movement, service forces such as janitors and, of course, retirees. Teachers’ protests have been the inspiration of many activists and organizations, both in terms of political content (demands and slogans that go beyond the ‘livelihood’ of teachers), and in terms of organization (spreading and multiplying this movement throughout the country; the role of the council coordination in the democratic unification of trade unions of each city; political stability in the face of security threats and repressions, etc.).” Collective 98, “The Bread of Freedom, The Education of Liberation: An Interview with a Comrade from the Teachers Movement,” collective98.blogspot.com, April 22, 2022 →.

For more on this, see Iman Ganji and Jose Rosales, “Tomorrow Was Shahrivar 1401: Notes on the Iranian Uprisings,” e-flux Notes, October 19, 2022 →. While “Jina Revolution” is the preferred descriptor used throughout this text, it is important to note that the mass of demonstrations and protests following Jina Amini’s extrajudicial murder remains a contested issue, even down to its name. Depending on one’s political sensibilities, intellectual training, and social background, the same political sequence is sometimes referred to as the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement, the “Jina Uprising,” or the “Jina Rebellions,” to name but a few.

“Blood Friday in Zahdan: The Brutal Government Crackdown of September 30, 2022,” Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, October 19, 2022 →.

Collective 98 and CrimethInc., “Revolt in Iran: The Feminist Resurrection and the Beginning of the End of the Regime,” crimethinc.com →. Emphasis added.

For the categories of “production struggle” and “circulation struggle,” see Joshua Clover, Riot Strike Riot (Verso, 2016): “Strike and riot are distinguished further as leading tactics within the generic categories of production and circulation struggles. We might now restate and elaborate these tactics as being each a set of practices used by people when their reproduction is threatened. Strike and riot are practical struggles over reproduction within production and circulation respectively. Their strengths are equally their weaknesses. They make structured and improvisational uses of the given terrain, but it is a terrain they have neither made nor chosen. The riot is a circulation struggle because both capital and its dispossessed have been driven to seek reproduction there” (46).

For more on the notion of the “suicidal state” vis-à-vis the Iranian state, see Iman Ganji and Jose Rosales, “Khuzestan: Riots Against the Suicidal State,” LUMPEN: A Journal for Poor and Working-Class Writers, no. 11 (Summer–Autumn 2022).

Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), trans. Institute of Marxism Leninism (1955), Marxist Internet Archive →. Emphasis in original.

CrimethInc., “Iran: ‘There Is an Infinite Amount of Hope … But Not For Us.’”

The notion of “political death” used here comes from Maurice Blanchot: “If today there is a politically dead man in this country, it is the one who carries … the title of President of the Republic, a Republic to which he is just as foreign as he is to any living political future. He is an actor, playing a role borrowed from the oldest story, just as his language is the language of a role, an imitated speech at times so anachronistic that it seems to have been always posthumous. Naturally, he does not know this. He believes his role, believing that he magnifies the present, whereas he parodies the past.” M. Blanchot, “Political Death,” Political Writings: 1953–1993, trans. Zakir Paul (Fordham University Press: 2010), 90.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 231.

Shirin Mohammad, Rebellion of the Slogans (Künstlerhaus Bremen, 2023). While the present essay largely deals with Rebellion in its printed booklet format, for an engagement with its corresponding exhibition see Niloufar Nematollahi, “Down with the Ordinary: Thinking Through ‘Rebellion of the Slogans,’” e-flux Notes, August 18, 2023 →.

ژینا گیان تۆ نامری. ناوت ئەبێتە ڕەمز serves as Jina Amini’s epitaph, which, translated into English, reads: “Beloved Žina, you will not die. Your name will become a symbol.”

As Mokhtari writes, “The leadership of the Iranian people’s revolutionary movement did not systematically and consistently participate in proposing slogans from the movement’s inception. As a result, the social psychology of the people and their capacity to decide on the necessary slogans, as well as their reactions to every action taken by the enemy, assumed critical significance.” “Study of the Slogans of the 1979 Uprising.”

Verónica Gago, “Is Politics Still Possible Today?,” Crisis & Critique 9, no. 2 (November 2022): 97–98. Emphasis in original.

Blanchot, “Political Death,” 95. Emphasis added.

Blanchot, “Political Death,” 100.

Collective 98 and CrimethInc., “Revolt in Iran.” Translation of the first chant modified.

Claire Fontaine, “This Is Not the Black Block,” in The Human Strike Has Already Begun & Other Writings (Mute, 2013), 20.

The “White Revolution” was a series of socioeconomic reforms implemented by the Shah of Iran between 1963 and 1979. The most notable reforms dealt with land and agricultural. The “white” color designation was intended to signal the “bloodless” nature of this “revolution.”

This formulation is a detournement of the original meaning given to it by Marx in his introduction to “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” where he writes, “Religion is the general theory of this world, its encyclopedic compendium, its logic in popular form.” To claim that slogans are the revolution’s “logic in popular form” indexes the scale, scope, and aspiration of this revolutionary period. Marx, “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” in Early Writings, trans. Rodney Livingstone and Gregor Benton (Penguin, 1975), 244.

Yasmine Ansari, “From Khavaran to Evin: Politics of Memory and the Slogans of the Jina Revolution,” May 4, 2023. Part of Künstlerhaus Bremen’s program organized around the “Rebellion of the Slogans” exhibition.

Mahdis Mohammadi, “Remembrance of Things to Come: Archiving Iranian Protest Movements,” May 4, 2023. Part of Künstlerhaus Bremen’s program organized around the “Rebellion of the Slogans” exhibition.

Peyman Jafari, “Fluid Histories: Oil Workers and the Iranian Revolution,” in Working for Oil: Comparative Social Histories of Labor in the Global Oil Industry, ed. Touraj Atabaki, Elisabetta Bini, and Kaveh Ehsani (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 77.

Quoted in Jafari, “Fluid Histories,” 79.

Jafari, “Fluid Histories,” 91.

The writing of this essay would not have been possible without the criticism, conversation, and education I received from too many comrades to name here. Any errors found herein fall entirely on the shoulders of its author, just as whatever remains true of this text is entirely due to the feedback and guidance comrades offered in the course of its writing. That said, I owe a special debt of gratitude to four comrades in particular, each of whom has always maintained the only “standard” worth speaking of (ruthless criticism) and without whose feedback this all-too-brief and incomplete survey would not have been possible. Momo, Shirin, Iman, Morteza: what is there to say except that I owe more than everything to each of you. May our steps be as great as our dead.