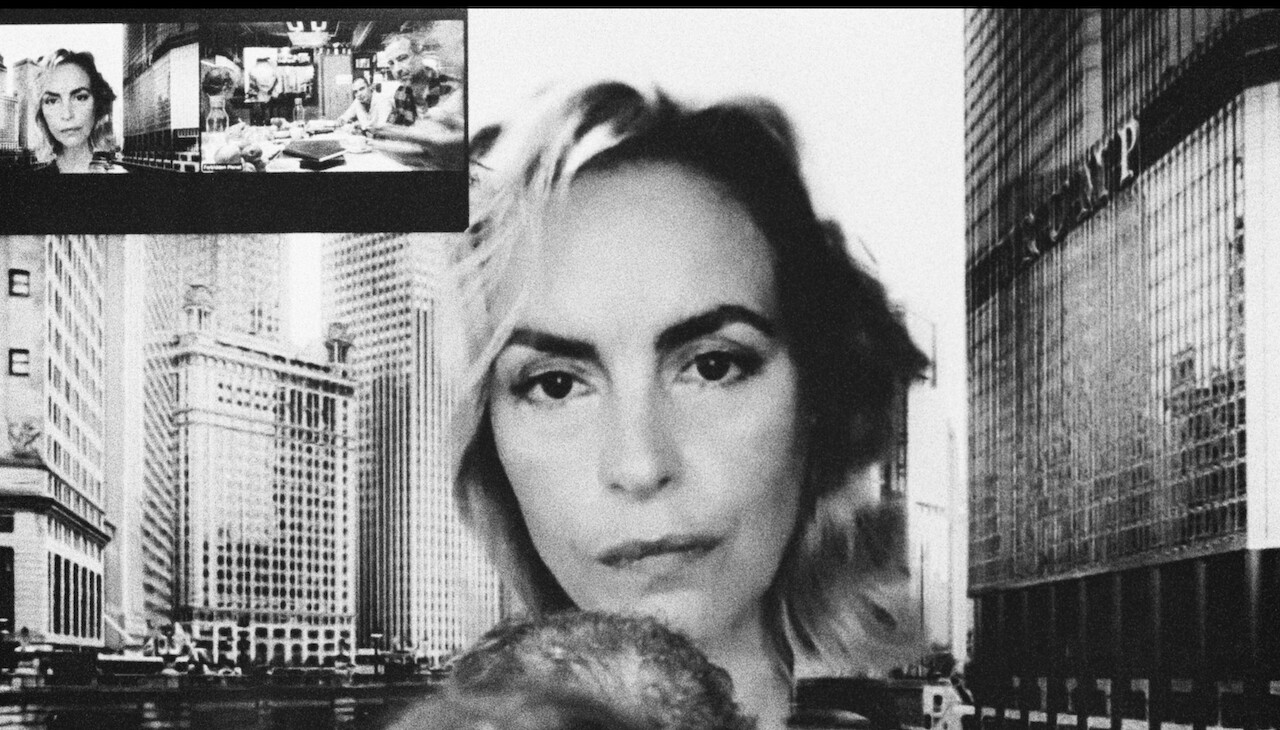

Film still from Radu Jude, Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World (2023)

Though it belongs among the so-called “Big 6” festivals (alongside Cannes, Sundance, Venice, TIFF, and Berlin), the Locarno International Film Festival in Switzerland regards itself as a different pedigree from the others—unfashionably twentieth century and patrician in its commitment to film as an autonomous and independent art form rather than just a potentially remunerative piece of IP. (The tagline for the town of Locarno overeggs this somewhat, declaring itself the “world capital of auteur cinema.”) Less commercial and industry-oriented than Berlin or Cannes, and (exempting the packed nightly screenings in the Piazza Grande) far less willing to pander to perceived audience preferences, its precise role in the “value-adding process” such festivals seek to perform is somewhat harder to determine. In any case, as a disgruntled local bookseller I met there on the final day lamented, one form of added value was unmistakably absent from this 76th edition—the visiting celebrities, this being the first major festival to run since the SAG AFTRA strike, which forbids actors from promoting their films. The closest one could get to the frisson of Hollywood stardom was therefore Harmony Korine, in town to receive the Pardo d’onore Manor award for outstanding achievement in cinema. Seemingly as flummoxed by the prematurity of this honor as everyone else (“Aren’t you a bit young to be writing your memoirs?”), a packed-out screening of Gummo on 35 mm nonetheless proved the perennial enfant terrible to be a more than worthy recipient. Rewatching his debut—so reviled upon its release by a blinkered critical establishment, which misperceived his deeply tender portrayal of the hicks of Xeno, Ohio as exploitative—I was struck anew by its dynamism and the twisted lyricism of its offbeat characters (such as the patricidal twin brothers beating one another to a pulp in their kitchen, or Linda Manz tap-dancing in a basement that looks like Jeff Wall’s Destroyed Room). Jean-Yves Escofffier’s compositions have also lost none of their power to enthrall.

The festival’s top prize, the Golden Leopard (Pardo d’oro), each year seeks to outmaneuver audience and critic expectations—sometimes to a slightly perverse extent. This year proved no exception. The Leopard went to Ali Ahmadzadeh’s Mantagheye bohrani (Critical Zone), a tonally indecisive stoner tragicomedy following a near-mute weed dealer with erectile dysfunction, who travels around Tehran at night speaking mainly to either his satnav or his bull terrier, and who also acts as a sometime confidant to a coterie of disaffected friends/clients (it’s never quite clear who is who). Shot in secret with hidden cameras, the film was defiantly screened by the festival despite strong countervailing pressure from the Iranian authorities. Ahmadzadeh was forbidden from attending in person but clarified in a statement that “instead of actors, I worked with real people. In most situations, we had to hide the camera or find complicated tricks to work around the limitations. Making this film was a big rebellion. Showing it means an even bigger victory for us.” As far away as one could imagine from the delicately poised postrevolutionary cinema of a Kiarostami, Farhadi, or Panahi, Mantagheye bohrani’s opiated, near-catatonic mood (made groggier by the muddy and uninspired film grading of its digital image) is eventually broken by a final sequence that delivers on the rebellion of which Ahmadzadeh spoke. The weed dealer has picked up his former lover (played by the Iranian artist Shirin Abedinirad), an air hostess who helps him traffic drugs into Iran. She raises herself out of the car’s sunroof and begins to scream profanities into the wind.

Elsewhere, this year’s program saw two dramatically counterpoised approaches to the migrant crisis. On one side there was Ken Loach’s The Old Oak (the third installment of the loose austerity trilogy he and Paul Laverty began with I, Daniel Blake, and an unsurprising recipient of the UBS Audience award—the festival’s sop to a sort of ersatz democracy). On the other was the second part of Sylvain George’s epic Nuit Obscures. In immediately succeeding press conferences the axes of differentiation between these two directors’ approaches to political aesthetics became unignorable. Loach’s film delivers a cloying and conventional story of how the arrival of Syrian refugees in a “left-behind” Durham mining town provides an opportunity to reawaken its dormant history of working-class solidarity. Typically paternalist and Dickensian in its execution, Loach’s affirmation that “hope is a political necessity” was here once more hamstrung by the director’s total indifference to any questions of the form his social realism might take, reducing the film to a bland, functionalist exercise that ultimately shores up the existing circulation of images of the “migrant”—a sort of long-play charity video.

George’s Nuit Obscures 2, by contrast, situated itself squarely within the avant-garde legacy of a Jean Vigo or a Jean Epstein, as well as the anti-fascist oeuvre of the filmmaking partnership Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi. It continues the director’s uncompromising documentation “with rather than of” a group of young “harragas” from Morocco, who find themselves temporarily moored in the Spanish autonomous city of Melilla en route to Europe. Harragas, translated as “those who burn,” are so called for their destruction of their identity papers. As they haunt the streets of this liminal threshold to Fortress Europe, seeking out any and all strategies for escape, the young men in George’s films are displaced outside and resist the existing economy of migrant images. He thereby restores to them the complex status of fully political subjects with agency. This is to say that they are reduced neither to the one-dimensional victims produced by the bad conscience of liberal NGOs (who are often in cahoots with the very same discriminatory policies that sustain their ordeal), nor the faceless hordes manufactured by the imaginary of neofascist politicians and tabloid journalists. These young men fight, they huff glue, they survive, they repurpose the city for their own ends, they show one another their scars and discuss their new lives to come, they sing the songs they’ve brought with them from the terraces of Moroccan football stadiums. Shot throughout in stark, high-contrast black and white (save for one brief, lysergic explosion of hyper-saturated color), the film skillfully dramatizes the politics of visibility surrounding both the harragas and the carceral border regime upheld in Melilla by the Guardia de Civille. In one of the film’s most arresting wide-angle shots, the young men run in the upper third of the frame toward the border fence that encircles the docks, while in the bottom third a rooftop cocktail party also runs along in full flow: both groups wholly oblivious to the other.

***

There were unsurprisingly plenty of what Christian Petzold has called “lemon-tree movies” to be found throughout the festival’s program. In Dennis Lim’s gloss, such a film,

would, as Petzold derisively imagines it, involve two lovers, one Palestinian and one Israeli, their star-crossed romance represented by a lemon tree situated right on the Gaza-Israel border … These are films that are relentlessly about something: laden with sociopolitical import, allowing for a touch of lyricism but very little ambiguity, and bearing the telltale traces of the screenwriting workshop.1

Such, for instance, was the case with Patagonia, the much-hyped debut feature from the young Italian director Simone Bozzelli. The film is a queer bildungsroman following the toxic entanglement of Yuri, a puckish young butcher, with a wayward crusty called Agostino, who he encounters working as a clown at a children’s birthday party. Here the lemon tree in question is the South American region of the film’s title, ham-fistedly plugged into the script with all the subtlety of a pop-up advert to represent the impossibility of either of these star-crossed lovers achieving the freedom they seek. Ena Sendijarević’s debut Sweet Dreams, meanwhile, seemed torn between a period drama “relentlessly about” its cartoonish depiction of Dutch colonists on a plantation in Indonesia, and a film with sequences that long for the dreamy historiographic metafiction of Ildikó Enyedi’s My Twentieth Century. As with several recent arthouse history films, however, the cheap ironies offered by the familiar and bankable visual language of Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Favorite won out, supplying the dominant model for Sendijarević’s exercise in pop decoloniality (meaning here: wide-angle fish-eye shots, natural lighting, off-center close-ups).

Standing apart from the lemon-tree films at Locarno were a superb crop of what could instead be characterized as “termite films.” In Manny Farber’s canonical essay, he defined “termite art” in the following terms:

The most inclusive description of the art is that, termite-like, it feels its way through walls of particularization, with no sign that the artist has any object in mind other than eating away the immediate boundaries of [their] art, and turning these boundaries into conditions of the next achievement.2

Such an omnivorous “eating away” at the boundaries of contemporary cinema and the repurposing of them for productive ends was ultimately what distinguished the two best films I saw at Locarno this year: Romanian director Radu Jude’s Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World (DNETMOTEOTW) and Argentine Eduardo “Teddy” Williams’s The Human Surge 3. Though in several ways visually and thematically distinct, both films were nevertheless united by their gnawing-through of our received or restricted understanding of what cinema can still accomplish—leaving such expectations riddled with holes. Which is to say they had in common a commitment to immanent formal contestation, engaging themselves in a relentlessly self-interrogating demand for images and stories adequate to a moment when filmmakers have long lost their formerly exalted status as producers of images and stories, within the dense image-world of advanced capitalism. (At his Q&A, Jude speculated on when a TikTok would show at Locarno.)

Jude’s DNETMOTEOTW is, like his I Do Not Care if We Go Down in History as Barbarians, bipartite in structure, with each part looping around to raise open questions of the other. The first part follows Angela (a memorable turn from Ilinca Manolache), a maniacally overworked production assistant casting members of the public for an infomercial on road safety, on behalf of a shady Austrian corporation that refuses to pay her on time (headed up by a pitch-perfect cameo from Nina Hoss). As she pulls graveyard shifts, stuck in continually gridlocked traffic, Angela sustains herself by downing energy drinks and listening to high-BPM turbofolk. Jude crosscuts this ultracontemporary story into a “dialogue” with reworked and time-lapsed footage from a 1981 Ceaușescu-era propaganda film called Angela Moves On, following a taciturn Bucharest taxi driver. The two stories are intercut into a genuinely odd parallelism that at once merges and diverges, as when the now-mobility-impaired actress who plays the original Angela meets the contemporary Angela to be cast for her road-safety infomercial. The final strand interwoven into this first section involves the tirades of Angela’s TikTok alter-ego “Bobita,” a vicious Ryan Trecartin–style scatologist concealed behind a monobrowed AI face filter who erupts in color into the otherwise high-grain monochrome of DP Marius Pandaru’s compositions. The second section then comprises the shooting of the infomercial for which Angela has labored so hard. As in Barbarians, through this anticlimactic ending we see the bathetic compromises that ideology demands, as the already watered-down infomercial is only further diluted in compliance with the client’s whims.

Unlike recent liberal anti-capitalist farces such as Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness, Michel Franco’s New Order, or Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite, which all sketch out their allegorical terrain with the broad strokes of a wide decorator’s brush, the satirical details in DNETMOTEOTW have the acuteness of a miniaturist’s single horsehair: from the copy of Kenneth Goldsmith’s CAPITAL which adorns the conference suite of the Austrian corporation for whom Angela toils, to her polyphonic “Ode to Joy” ringtone, to the director’s own brief cameo in a building lobby as a GLOVO delivery driver. The resulting film is a formally audacious and scabrous “humorless comedy” (as Jude terms it), delivering Bakhtin’s carnivalesque through the medium of Alexander Kluge’s critical montage—to whom Jude stands as the true heir, despite the frequency with which he is compared to Godard.

Like Jude, Teddy Williams isn’t a filmmaker content with slipping into the straitjacket of a restrained or recognizable arthouse vernacular. Following the premiere of the first The Human Surge film at Locarno back in 2016, its successor The Human Surge 3 is, like Michael Snow’s La Region Centrale (to which it bears more than a passing resemblance), one of those rare and anomalous visual objects that stress-tests the plasticity of one’s ontology of what might even count as a “film.” For some, such as the septuagenarian Swiss critic I met at the press dinner high up in the cloisters of the San Franscesco church, or the pair of French journalists who sat behind me in the screening nervously explaining to one another what a “glitch” was, before shuffling out of the cinema early, it evidently proved too much. Filmed across three continents, using a 360-degree camera mounted in a backpack, the film loosely tracks a group of friends as they engage in various meandering quests from Taiwan to Peru and Sri Lanka, frequently in landscapes devastated by climate catastrophes. That’s about as close an appraisal as one can get, plot-wise. Williams meanwhile burrows down deep, termite-like, within the fine grain of his 360 camera and the numerous affordances of its images, particularly exploiting the “join” that digitally composites its eight different camera images into one image along the upper and lower seams to effect prismatic and lysergic compositions. Instead of determining the framing of his shots on set, the precise framing happened partially in postproduction on the computer and partially through the movements of his own head as he explored its visual environment in a VR headset—lending the camera’s inquisitive “movements” the queasy, proto-algorithmic quality of auto-tracking video-conferencing software. Unlike the overbearing use of anamorphic squeeze lenses in, for instance, Alexander Sokurov’s work, we actually find ourselves rapidly adjusting to this new way of seeing. This is because the world as perceived by The Human Surge 3 is in fact our own. It resembles nothing so much as our routine navigation of digital environments like Google Street View, or the jerky joystick-determined explorations we make with our controllers throughout richly rendered open-world RPGs, or indeed the way we scan our surroundings for clues through the 3 mm ultrawide lenses of our iPhones. At times maddening in its stubborn refusal to bow to narrative convention, but never anything less than visually arresting, The Human Surge 3 may resist easy interpretation but, to quote Annette Michelson writing of Michael Snow, “Interpretations offer an easy escape route from the challenge offered by this film to your sensibility.”3