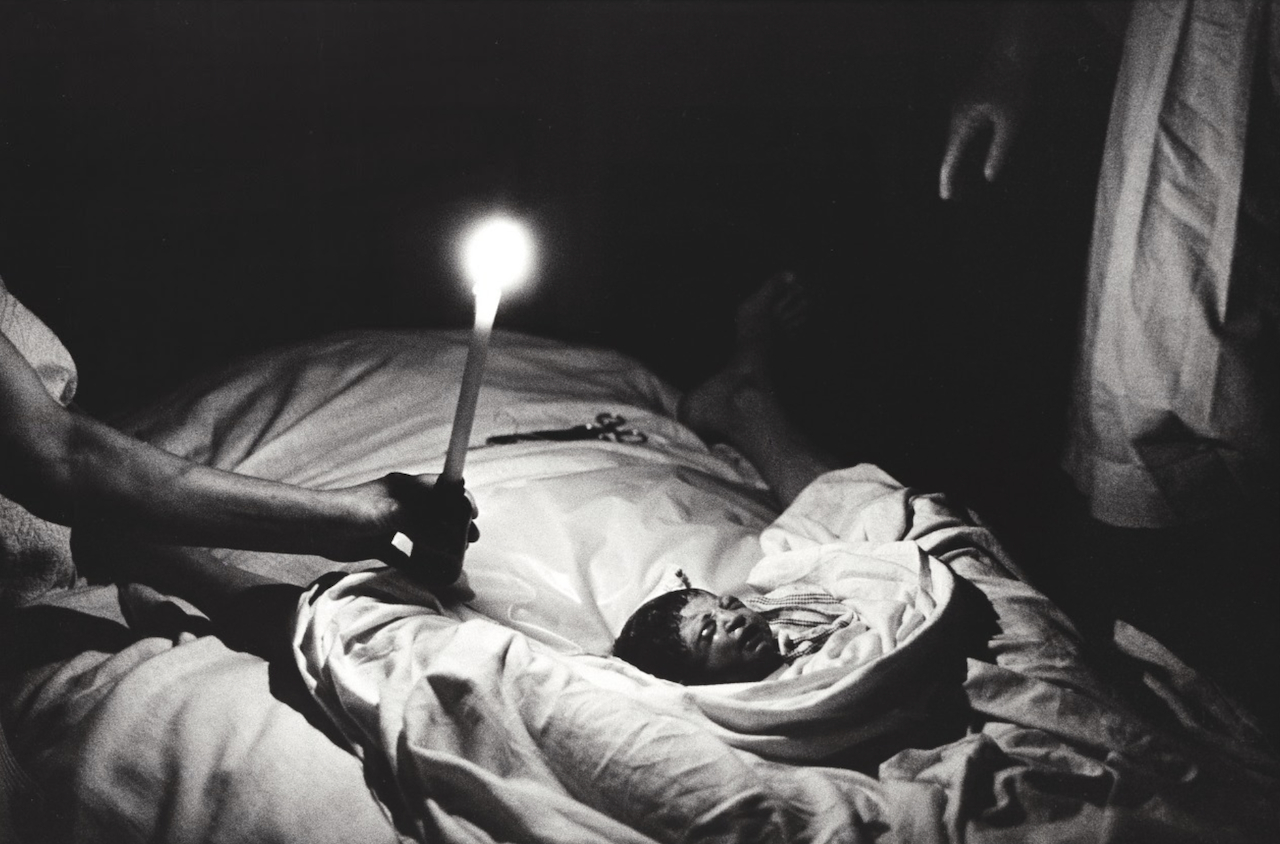

Claudia Andujar, A Child is Born (#2), 1966.

in these latitudes

of indeterminate

waves

in which all reality dissolves

—Mallarmé, A Throw of Dice Will Never Abolish ChanceYou have to hand over your shadow to the Beast of the Deep

You have to cast a spell when the moon is new

You have to drink three drops of blood.

—Raul Bopp, Cobra Norato

It is no secret to anyone anymore that there is a motherless Yanomami child sleeping on the upper floors of a gallery on the island of Manhattan. But no inhabitant of the West Village can hear the child snore, and none of the visitors have the least idea of her dreams while staring at her mute face. The child sleeps inside the gallery for many months without a cry or whimper, while spectators from around the world come to gaze at her. She has grown up, I believe, in many galleries like this. And amidst their silent, ordinary splendor of grayness, their suspended panels of picture after picture where the child’s people are frozen in the indeterminacy of their wounds through Claudia Andujar’s aperture, the galleries and exhibitions seem to ignore that a child sleeps without a mom to wake her up. That the river behind her may take her to the unknown. Or may tear the child apart in the stupor of drowning. But it would be useless and futile to try to awaken her as I did, gently whispering, “Good morning” to an image on a wall, because when you try, it becomes just this: an image on a wall. Which is not any less real but all the more unsavable.

Perhaps the most drastic and tangible conclusion that may be drawn from an exhibition of dire and somber conclusions about the haunting scope of the disaster and crime perpetuated by the Federal Republic of Brazil against generations of the Yanomami native people is that this child will not wake up. This makes one fear the worst.

But when one ultimately realizes that the child will not drown, that although she does not look back with her closed eyes, everything is okay, and the exhibition has been going on for many weeks now without any reports of incidents or turmoil—after all, photographs are always safe in their stillness—the heart can beat more slowly, and one can read the note beside the picture where the Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa writes, perplexed: “Is this girl dead or sleeping? I got a little angry with her. When the eye is closed, you can’t take a picture because it’s dead. I think she is sleeping.”

In pictures that have become indistinguishable from a chronicle of the genocide of a people and a mode of living in all its gloomy dimensions of horror and crime, it’s puzzling how Kopenawa’s question is lost in a sidenote, as it captures what is at stake in Andujar’s work. From the pictures that mimic the hallucinogenic effects of yakoana powder—which the Yanomami inhale to induce a trance state and summon their spirits (xapiris)—to elaborate double exposures and slow shutter speed, to the static bleak portraits of Yanomami people swallowed by the machines of modernity, turned into sore and bruised workers along highways, Andujar’s work asks, across the many decades it spans, from Brazil’s military dictatorship to Bolsonaro and his aesthetics of ashes, hauntingly over and over again: Is she dead or sleeping? The picture doesn’t know.

Dead. Irrevocably dead. In the inescapable violence of the mercury polluting the rivers. In the poisoned fish and vanishing ecosystems. A now of doom, shaped by the unforgivable. But simultaneously, impossibly, by magic, sleeping too in this same vanishing trace of the future is an endless vision of the possibility of daybreak, of an awakening that could survive everything, that could endure the miners, the governments, and all the depletion since the beginning of the immemorial war between world and nature. This is the greatest triumph of Andujar’s works, its greatest mystery—that the genocide, the mourning, and the tragedy can coexist with the nap, the resting, and the promise of surviving all things, even what remains so real.

Is she dead or sleeping? To pose this question, this coexistence, is to ask the picture not to decide on the Yanomami people’s future or any other matter—which, in any event, it isn’t able to do—but to confront technological images themselves in their misty realm and make them face a plain and devastating accusation: What have you done to the real? Where did it go? Is it dead or sleeping somewhere in this suspension of time where every face is already a specter that has decided to close its eyes to us in indecision regarding what is happening and what may come to pass? What may happen to us—death or sleep?

The misty realm of images is indissociable from a certain circularity of the eye. A circularity of the wandering of the gaze that, as Vilém Flusser once pointed out, “tends to return to contemplate elements already seen. Thus, the before becomes the after, and the after becomes the before. The time projected by looking at the image is eternal return.”1 The eternal return is a time “that circulates and establishes meaningful relationships.”2 This is the time of magic, Flusser writes, where everything is reversible and this reversibility alienates humans in their incapacity to recognize that images were made to orient them and are not pure reflections of reality. For Flusser, “the struggle of writing against the image, of historical consciousness against magical consciousness, characterizes all of history.”3 And history necessarily ends precisely when texts become unimaginable and unrepresentable:

The crisis of texts implies the shipwreck of all History, which is strictly speaking a process of recoding images into concepts. History is a progressive explanation of images, disenchantment, conceptualization. There, where texts no longer signify images, nothing is left to be explained, and History stops. In such a world, explanations become superfluous: absurd world, current world.4

This absurd post-historical world is precisely where Flusser believes photography emerges as a return to the time of magic, to what he calls second-order magic in the sense that

pre-historic magic ritualizes certain models, myths. Today’s magic ritualizes another type of model: programs. Myth is not elaborated within the transmission since it is elaborated by a “god.” A program is a model elaborated within the transmission itself by “functionaries.” A new magic is the ritualization of programs, aiming to program their receivers for a programmed magical behavior.5

In the concepts of “programs” and “functionaries” lies the essentials of Flusser’s original philosophy of photography. The program is symbiotic to manufacturing the technical object, to the camera, which has had limited symbolic potentialities since the beginning—all the possible images one can take. These potentialities, the possible images, are precisely its program; all the possible information that the photographic universe can convey is from the start part of the camera. In the concept of the program, it is already disclosed that post-historical photography cannot transform reality but only reveal the photographic program in the form of a photographic universe. This allows Flusser to state that the

photographer acts in favor of the depletion of the program and in favor of the realization of the photographic universe. Since the program is very vast, the photographer makes an effort to discover ignored potentialities. The photographer manipulates the device, feels it, looks inside and through it in order to always discover new potentialities. His interest is concentrated on the device, and the outside world only interests him, depending on the program. He is not engaged in changing the world but in forcing the apparatus to reveal its potentialities. The photographer does not work with the device, but plays with it.6

Play is the essential modality not only of photography but of post-historical, postindustrial civilization, not as an emancipation of work but as work without separation from the apparatus. Work is only possible within the apparatus, which is indistinguishable from the exploration and revelation of its programs; power shifts from property to information that invents and realizes the program through play. But play, as Flusser notes, is only possible if there is an impenetrable opacity within the apparatus that makes its potentialities and program inexhaustible and fuels the functionary to go on exploring its darkness. The complexity and impenetrability of the apparatus’s system are what allow Flusser to call it a black box, and this is what photographers play with, losing themselves in the shadows, swallowed in the intentions and worlds of unrepresentable and unfathomable others, but still managing to assert a measure of resistance, amidst this self-sustaining program that is not theirs.

The Amazon was always Brazil’s black box. Its incomprehensible grandeur, its sophisticated and miraculous nonhuman interactions between millions of species, and its native cultures of spirits were always too much for a country on the margins of history, a country too easily seduced by the daydreams of modernity and without the imagination to flee them. Brazil as a nation and state could never see the Amazon, its reality was too challenging. In its place, the country created a mirage of mining, agriculture, and cattle which lured millions of men north, encouraged by the military dictatorship and its paranoia to build something rather than the nothing they saw there. It’s no coincidence that the phrase repeated most often by these settlers was that when they arrived, there was “nothing there.” Now this “nothing” is a vast wasteland bleeding carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, while rivers spew sickness and transport empires of drug dealers who, along with financial speculation on doom pastures, shamelessly fuel the end of the world. In this transformation of an incomprehensible nature and its cosmic forces into the all-too-familiar Christian apocalypse of opened seals and falling skies, the Yanomami people are at the edges of the image, suffocated, poisoned, tortured into giving up their way of life, their spirits, and joining the totalizing machine of the world, yet still somehow trying to be. These edges are the raw material of Andujar’s photographs, where in the meeting of black boxes—the camera and the rainforest—one can hear the cries of earth and life in unison in the face of so many annihilating programs.

In the Amazon’s occupation, deforestation, burning, and genocide, an annihilating program is playing nonstop. In the miners’ machinery, the machine guns of the agriculture landlords, and the microchips implanted in cattle, it’s as if something moved with the relentlessness of an automaton, like the Enforcement Droid Series 209 from Paul Verhoeven’s 1987 RoboCop, programmed towards death, no matter the cost. This what law enforcement has become in the Amazon: special forces as RoboCops, burning camps and houses in the world’s most secret war that, in its impotence and tautology, resembles the farce of the war on drugs.

In between two other faces—those of the Roman god Janus—Hito Steyerl speaks to a crowded auditorium on a Saturday morning in Manhattan. It’s not a minor detail that her talk about AI images happens in a cinema, with the silver screen hovering over Steyerl like an immense dinosaur from a natural history museum. Projected onto the screen are images of animals with many faces generated by a Janus-like AI glitch effect. Halfway through the talk, Steyerl stops to show a picture of herself made by artificial intelligence. There, instead of two faces, what appears is a collage of time, her hair falling out, her cheeks aged. But after the abrupt and fulminant aging, everything seems to freeze cryogenically, as the aging can go no further and miraculously stops. The Romans’ famous prayer to Janus to be their keeper of time seems to materialize in this frozenness, in this solidification of a form that can be reversed, as if nothing was ever outside of its totalitarian miracle. Steyerl proceeds to talk about weather forecasts in which one can see clouds made purely of data.

These are images of texts, of black boxes without any trace of light, of prompt-generated rain showers wetting their functionaries, total playthings, perpetual Adobe subscribers—thunder sound. Steyerl leaves, the auditorium empties, and the cinema screen remains staring: the spectacle is over, the specters, passive and dangerous, from Lumière’s train to Debord’s suicide, have vanished into thin air. It is playtime.

The thunder does not awaken, for now, the Yanomami child, who lies not far from that auditorium on the upper floor of a Manhattan gallery. The walls, and the framing of the image, protect her from outside noise, but more importantly, they still protect us from her. The wall, delimiting the picture’s space, does not demand that we come and play and be engulfed too in all the grief of the world. But not for long. Flusser concludes that “the photographic universe is one of the apparatus’s means of transforming men into functionaries, into stones in its absurd game”—functionaries of the apparatus’s goal, namely, “to carry out its program, that is, to program men to serve as feedback for its continuous improvement.”7 If this is true, the undisputed victory of the photographic universe and its sustainability in our photographic illiteracy, in the invisible violence of the omission of the photographer’s gesture, has allowed not only for the Pope’s fake coat and Donald Trump’s arrest pictures but a black box that can swallow the world in all its symbolic and imaginary dimensions, turning every individual into a spectral player with no place to hide in the machine’s frozen blind time. A player confined to the invisible edges too, of every prompt-generated image, until it vanishes through the program’s feedback. Until it disappears in all the atemporal noise of artificial intelligence.

Kittler once said that “everything of the real falls under the category of noise.”8 Real here is understood in its Lacanian sense as that which escapes representation, evades language, and is always traumatic. As that which sustains the symbolic and the imaginary, but remains hidden in it. Kittler ties the real to the gramophone because there, in the incapacity of filtering, sound emerges as a primal cry before language where “the real takes the place of the symbolic.”9 Nonetheless, in the world-encompassing black box that constantly and addictively swaps text for image, symbolic for imaginary, the uncontrollable multiplication of this murkiness, of this time of return in pictures, is noise. The players inside the penumbra face no specters because they wouldn’t be able to distinguish them in the shadows; they become only sounds of chainsaws, engines, motors, and machine guns, like those strangling the heart of the Amazon. There is no Lacanian can of sardines to sparkle on the sea or ray of light to disclose the gaze of the other. The player is part of a total symphony of noise and will either disharmonize it in the open wound of material time, prophesying that “the blood-covered head of Christ will arise unexpectedly from the broken machine” to resurrect the dead, or will keep playing snobbishly until all time becomes a distant sound without an echo.10 But the Yanomami child will have to open her eyes amidst all this unbearable noise. And if there is any viewer left on earth, they will be able to see in these fossils on the walls what we have done to the world. They will finally figure out if we were dead all along, or if we have just woken up, motherless and dreamless, in the midst of galleries and exhibitions, mumbling to the enclosed future: sleep no more.

Vilém Flusser, Filosofia Da Caixa Preta: Ensaios Para uma Futura Filosofia Da Fotografia (Hucitec, 1985), 7. My translation.

Flusser, Filosofia Da Caixa Preta, 7.

Flusser, Filosofia Da Caixa Preta, 7.

Flusser, Filosofia Da Caixa Preta, 9.

Flusser, Filosofia Da Caixa Preta, 9.

Flusser, Filosofia Da Caixa Preta, 15.

Flusser, Filosofia Da Caixa Preta, 6, 24.

Friedrich A. Kittler and John Johnston, Literature, Media, Information Systems: Essays (Routledge, 2012), 140.

Friedrich A. Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter (Stanford University Press, 2006), 24.

Hugo Ball, Flight Out of Time: A Dada Diary, ed. John Elderfield (University of California Press, 1996), 160.