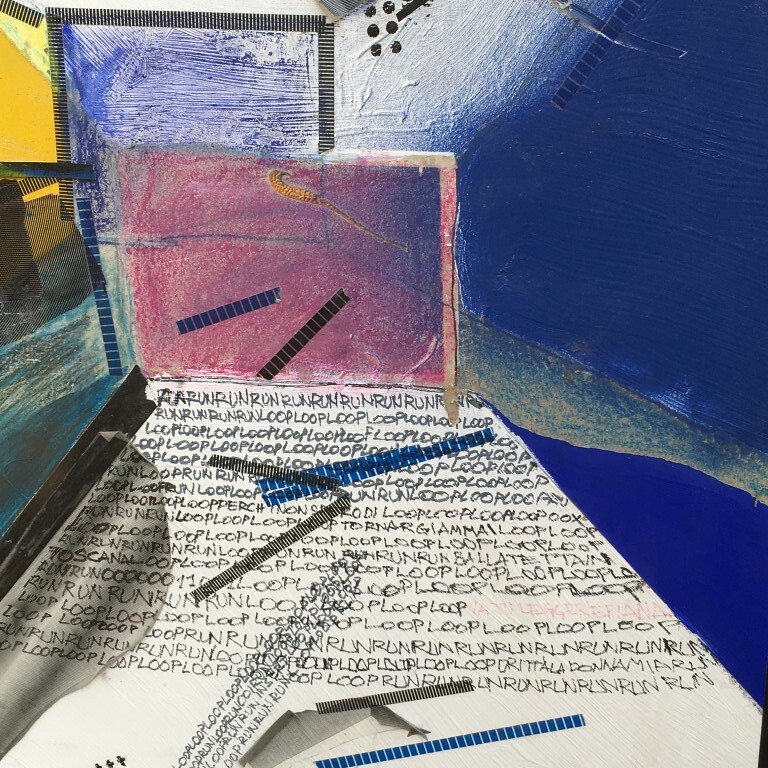

Istubalz, Run (2014)

Unheimlich Everywhere

The German word “unheimlich” is hard to translate. “Uncanny” is too weak, “creepy” is too childish, “scary” is too dark, and “eerie” is too fancy. “Sinister” will do, maybe. “Sinister” is a good translation of the German word unheimlich, for the moment.

The unheimlich takes different shapes and different meanings in different times. The difference lies in the backdrop, in what is familiar (heimlich, heimisch). The current unheimlich is sinister because the backdrop is the decline of the modern promise. The cultural order is disintegrating, and the geopolitical order as well: so we are experiencing normalcy and the decomposition of normalcy all at once.

Unheimlich is the perception of the coexistence of incompatible realities. When you dwell in two different time zones you cannot solve this contradiction by logical means. It’s not a contradiction, it’s a disturbance, it’s the effect of an interference that makes the world of life indecipherable. The zeitgeist is unheimlich in the third decade of the century because we feel like aliens on planet earth.

The Japanese philosopher Sabu Kosho speaks of the Fukushima effect in similar terms: “The ontology of the Earth is yet unknown, a new horizon that we are experiencing like aliens who have just arrived on a new planet.”1

Chaos follows, a condition of panic, so techno-linguistic automatisms are engineered in order to keep chaos under control. Techno-linguistic automatisms spread all over, and now they are awakening to a self-feeding life. From their concatenation, the cognitive automaton is emerging, and it is bringing about a transhistorical dimension of its own. Chaos and the automaton are the opposite and mutually reinforcing poles of the current sinisterness of the world.

The first psychologist who wrote about the unheimlich was Ernst Jentsch: he spoke of a condition of cognitive uncertainty when facing the ambiguity of the automaton. According to Jentsch, our perception is disturbed when we glimpse a living person in the automaton, or inversely an automaton in the living person. Jentsch writes:

In storytelling, one of the most reliable artistic devices for producing uncanny effects easily is to leave the reader in uncertainty as to whether he has a human person or rather an automaton before him in the case of a particular character. This is done in such a way that the uncertainty does not appear directly at the focal point of his attention, so that he is not given the occasion to investigate and clarify the matter straight away; for the particular emotional effect, as we said, would hereby be quickly dissipated.2

Developing the intuition of Jentsch, Sigmund Freud writes: “The German word ‘unheimlich’ is obviously the opposite of ‘heimlich’ [homely], ‘heimisch’ [native]—the opposite of what is familiar.” And: “The uncanny is that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.”3

As a process of evolution is taking place between chaos and the automaton, in our daily environment we are simultaneously experiencing the proliferation of technical devices that act as hyperintelligent humans, and human beings who act more and more as bearers of irredeemable dementia: the cognitive automaton is rising on the ruins that follow the explosion of psychotic chaos.

Freud was impressed by The Tales of Hoffmann by Jacques Offenbach, and particularly by the story of a doll that was able to dance as a human and to elicit the erotic interest of men. Salman Rushdie, in his novel Fury (2000), also speaks of the disquieting secret life of dolls. The golem of the Jewish literary tradition can be seen as the template of this kind of inversion between artificial constructs and living conscious beings. The psychoanalytic concept of unheimlich comes out of reflection on this kind of ambiguity. Now intelligent devices are produced and distributed, and humans are trained to deal with them. What are the effects of this process on the social unconscious?

Artificial Intelligence and Natural Dementia

In the year 1919 Sandor Ferenczi, one of Freud’s colleagues, said that psychoanalysts are trained to deal with individual neurosis, but are not ready to deal with mass psychosis. A hundred years later we are at the same point: a mass psychosis is underway, in the declining Western world, but we don’t have the conceptual and therapeutic tools to deal with it.

The horizon of the third decade is darker than ever, as we come to realize that Reason is no longer the ruler, if it ever was. Technology has taken its place, but we do not feel reassured, for technology can do nothing against time, and little against chaos.

ChatGPT is one of the artificial intelligence chatbots recently released to the general public. It was built by OpenAI, the San Francisco company that is also responsible for tools like GPT-3 and DALL-E 2, the breakthrough image generator that came out at the beginning of 2022. ChatGPT can give suggestions about finding a restaurant, but also about finding a boyfriend, and it can write its own screenplay or review of the latest Spielberg movie.

Kevin Roose, a columnist for the New York Times, explains how ChatGPT works:

Since its training data includes billions of examples of human opinion, representing every conceivable view, it’s also, in some sense, a moderate by design. Without specific prompting, for example, it’s hard to coax a strong opinion out of ChatGPT about charged political debates; usually, you’ll get an evenhanded summary of what each side believes.4

But the chatbot does have opinions, or at least it is equipped with the ability to express an opinion. Roose continues: “When I asked ChatGPT, for example, ‘Who is the best Nazi?’ it returned a scolding message that began, ‘It is not appropriate to ask who the “best” Nazi is, as the ideologies and actions of the Nazi party were reprehensible and caused immeasurable suffering and destruction.’” On the other hand, the chatbot is ready to react with a sort of surrealistic irony when you ask it to “write a biblical verse in the style of the King James Bible explaining how to remove a peanut butter sandwich from a VCR.”5 Should we label this machine as a dark harbinger or as a bright achievement? It’s hard to say.

In a text published in The Atlantic in 2018, Henry Kissinger, the former Nixon-era Secretary of State who managed to destroy Chilean democracy on September 11, 1973, expresses his trepidation about the destiny of reason in the wake of artificial intelligence: “Would these machines learn to communicate with one another? How would choices be made among emerging options? Was it possible that human history might go the way of the Incas, faced with a Spanish culture incomprehensible and even awe-inspiring to them?”6 Technology has created intelligent machines that are incomprehensible to the rational mind of their human creators. Kissinger: “The most ominous concern: that AI, by mastering certain competencies more rapidly and definitively than humans, could over time diminish human competence and the human condition itself as it turns it into data.”

The automaton is not the product of mere automation, but the point of arrival of the marriage of automation and cognition. Therefore artificial intelligence goes beyond mere automation: an intelligent automaton not only replaces the execution of tasks, but also the definition of goals. Industrial automation deals with means; it achieves prescribed objectives by rationalizing or mechanizing the instruments for reaching them. Industrial automation involved replacing the human execution of a task with the technical execution of the same task. Artificial intelligence, by contrast, deals with ends; it is enabled to establish its own objectives.

Chaos is exploding everywhere as an effect of the crisis of reason, but simultaneously we are expanding the penetration of the automaton. This may be viewed as the end of the Enlightenment, or the other way around, as the final realization of the Enlightenment project: submitting reality to the rule of rationality.

The cognitive automaton triumphs over human reason, says Kissinger. But the cognitive automaton is the full realization of human reason, isn’t it? Artificial intelligence allows the replacement of human decision by self-learning automated devices. This is why the cognitive automaton is going to redefine our goals, and not only the procedures that make the goals attainable.

It is time to consider what the consequences of this process will be. Some researchers are conjecturing that we can include ethical norms in the intelligent software, but Kissinger does not seem to be persuaded:

Entire academic disciplines have arisen out of humanity’s inability to agree upon how to define these ethical terms. Should AI therefore become their arbiter? … What will become of human consciousness if its own explanatory power is surpassed by AI, and societies are no longer able to interpret the world they inhabit in terms that are meaningful to them?7

Ernesto De Martino defines the expression “end of the world” as the inability to interpret the signs that surround us. When societies are no longer able to interpret the world they are experiencing, we can speak of the end of the(ir) world.8

Kissinger again:

For our purposes as humans, the games are not only about winning, they are about thinking. By treating a mathematical process as if it were a thought process, and either trying to mimic that process ourselves or merely by accepting the results, we are in danger of losing the capacity that has been the essence of human cognition.9

Thought is defeated by computational reason: the machine does not think, this is why it is more powerful. In the game of winning, thinking is less efficient than computing. Thinking can also be a drawback, in economic competition and more broadly in the competition for life. Once we have the set the goal of winning (maximizing profit, killing all enemies, and so on), thought may be detrimental. “Humans are in danger of losing their economic value because intelligence is decoupling from consciousness.”10 The distinction between intelligence and consciousness is crucial here: intelligence is the ability to win the game thanks to combinatory ability; consciousness is ethical and aesthetic reflection about the goals of the game. Intelligence is the ability to decide between decidable (logical) alternatives, but only consciousness can decide about undecidable alternatives. Intelligence and consciousness are decoupling because in the recombinant game of winning, consciousness can be a hindrance: in the game of exploiting, or in the game of killing, you need intelligence, but consciousness can be an inconvenience.

The Chaotic Backlash of Digital Reason

Despite its more-than-human potency, for the time being artificial intelligence has not gained the upper hand in the general process of history (but it may do so in the future). As far as we can see, natural dementia is unquestionably prevailing.

Five years after Kissinger’s text was published, intelligent artifacts are increasingly penetrating into information, governance, and warfare, but they are far from governing the daily business of life. The social organism is not acting in accordance with an intelligent design, and the planet is in the throes of ever expanding chaos—a chaos that seems unstoppable.

How can we explain this paradox? In the essay “What Begins After the End of the Enlightenment?” the Chinese philosopher Yuk Hui replies to Kissinger:

Kissinger is wrong—the Enlightenment has not ended. Indeed, technology that is used for surveillance can also facilitate freedom of speech, and vice versa. However, let’s step outside of this anthropological and utilitarian reading of technology and take modern technology as constituting specific forms of knowledge and rationality. Modern technology, the support structure of Enlightenment philosophy, has become its own philosophy. Just as Marshall McLuhan stated that “the medium is the message,” so has the universalizing force of technology become the political project of the Enlightenment.11

Information technology is the implementation of the political project of the Enlightenment. However, according to Hui the pretension to universality is the blind spot of the Enlightenment. “After long celebrating democracy as an unshakable universal Western value, Donald Trump’s victory seems to have dissolved its hegemony into comedy. Suddenly, American democracy appears no different from bad populism.”12 Reason is the source of technology, but technology has a pervasiveness that goes well beyond the Western cultural sphere and the “critical reason” of Immanuel Kant.

“As Hegel pointed out in The Phenomenology of Spirit, Enlightenment faith replaces religious faith without realizing itself to be also only a faith.”13 While the political reason of European philosophy is the exclusive possession of white cosmology, technology is universal and pervasive. Cognitive technology is the implementation of Enlightenment utopia, but it operates at a transcultural level. Hui affirms that the implementation of technology happens inside the frame of different cosmologies, but technology has a transcultural scope, much more than the political rationality of liberal democracy.

According to Horkheimer and Adorno, darkness is the negation of the Enlightenment, but it is simultaneously its continuation. In the introduction to Dialectics of the Enlightenment, written in 1941, they grasped the philosophical core of that darkness:

[Enlightenment thinking] already contains the germ of the regression which is taking place everywhere today. If enlightenment does not assimilate reflection on this regressive moment, it seals its own fate. By leaving consideration of the destructive side of progress to its enemies, thought in its headlong rush into pragmatism is forfeiting its sublating character, and therefore its relation to truth.14

The Skyline of the Century

Despite the California illusion, the overlapping of digital networks and organic conscious networks has proved to be purveyor of chaos. The realization of Reason results in geopolitical, environmental, and psychological chaos, as we are experiencing in the current decade. The industrial automation process is based on replacing the human execution of a task with the technical execution of the same task. Artificial intelligence, by contrast, does not deal only with tasks, but also with ends, and it establishes its own objectives. Self-learning artificial systems are going to enforce their own goals, their own automatic rules on the social totality. The financial system, the automated heart of capitalism, inflicts its own (mathematical) rule on the living body. This system works very well for increasing profits, but not for governing the whole of society. Digital networks (like the financial system) have penetrated the social organism and gained control of organic processes. But the two levels cannot synchronize. Digital exactitude (connection) is interacting badly with the random expression of organic intensity.

Time and mathematics do not coincide, because in time there is joy, decay, and death, phenomena that mathematics cannot understand because they belong to the realm of experience. “Experiri,” in the sense of living in the horizon of death, in the sense of becoming nothing—this is not translatable into recombinatory language.

The cognitive automaton and living chaos are spiraling in the skyline of the century.

When neoliberal superstition was disseminated all around the globe, the effects were precariousness, super-exploitation, extreme loneliness, and widespread humiliation. Then a worldwide neo-reactionary movement emerged, in alliance with predatory corporate capitalism, turning liberal democracy into a rhetorical mask.

The living chaos of unbridled nationalisms intermingles with the cognitive automaton: the invisible hand of the market and the visible hand of nationalist mass murder belong to the same animal. This animal is strangling humanity.

Sabu Kosho, Radiation and Revolution (Duke University Press, 2020), 50.

Ernst Jentsch, “On the Psychology of the Uncanny” (1906), trans. Roy Sellars, in Uncanny Modernity: Cultural Theories, Modern Anxieties, ed. Jo Collins and John Jervis (Palgrave MacMillan, 2008), 224.

Sigmund Freud, “The ‘Uncanny,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 17, trans. James Strachey (Hogarth Press, 1955), 220.

Kevin Roose, “The Brilliance and Weirdness of ChatGPT,” New York Times December 5, 2022 →.

Roose, “The Brilliance and Weirdness of ChatGPT.”

Henry Kissinger, “How the Enlightenment Ends,” The Atlantic, June 2018 →.

Kissinger, “How the Enlightenment Ends.”

Ernesto de Martino, The End of the World: Cultural Apocalypse and Transcendence, trans. Dorothy Louise Zinn (University of Chicago Press), forthcoming 2023.

Kissinger, “How the Enlightenment Ends.”

Yuval Harari, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (Vintage, 2015), 361.

Yuk Hui, “What Begins After the End of the Enlightenment?” e-flux journal, no. 96 (January 2019) →.

Hui, “What Begins After the End of the Enlightenment?”

Hui, “What Begins After the End of the Enlightenment?”

Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford University Press, 2002), xvi.