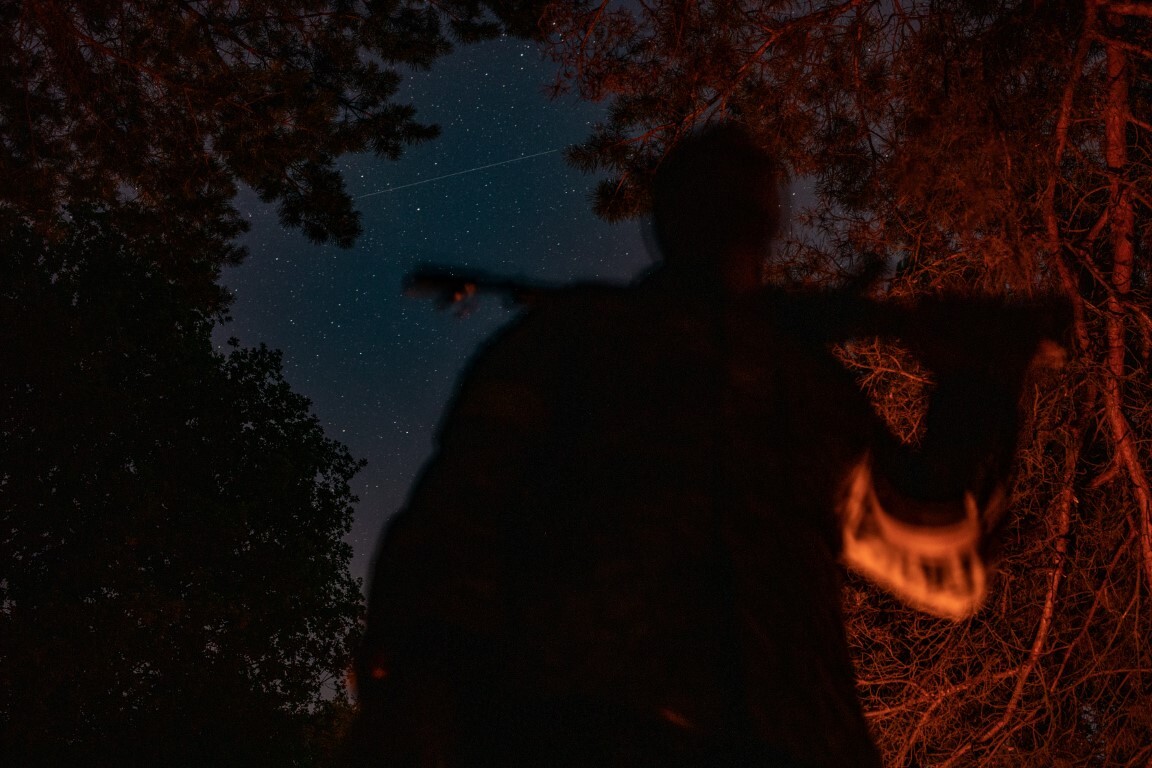

Self-portrait by Kostiantyn Polishchuk. Digital image, 2022.

For many years, anthropologist and documentary photographer Kostiantyn Polishchuk has worked as a political photojournalist. However, on February 24, 2022, when the full-scale Russian invasion began, he joined the Kyiv territorial defense and Ukrainian armed forces. We planned this conversation several times. Last month he participated in the liberation of Kherson, and we spoke a couple of days before the city was officially liberated. Polishchuk still works with images, though instead of a professional digital camera to photograph political figures, he uses a drone and thermal imager to search for Russian forces. This interview is an attempt to understand the image of war and the role of photography today.

—Kateryna Iakovlenko

***

Kateryna Iakovlenko: I was thinking of war photography, and the connection that can be made between shooting in the army and shooting in photography. Did your war experience change your view on photography, and how?

Kostiantyn Polishchuk: This war is not about small arms; it is a war of drones and artillery. Many people who have directly taken part in battles confirm that they never fired at the enemy and have not fought face to face. My attitude towards photography has almost stayed the same. I studied photography with Viktor Marushchenko [1946–2020, a Ukrainian photographer whose series Chernobyl (1986) was exhibited at the main exposition of the Venice Biennale in 2001], who presented photography as a kind of universal language that can work in different ways.

My specialty is documentary photography, which is appropriate in war as well. In war, everything happens quickly, and quick decisions need to be made. Although people today follow TikTok, not many things have changed since the days of Robert Capa, the Magnum agency, and Life magazine. Photography can still powerfully convey emotion. Yes, it is similar to small arms, but today I prefer to speak about drone cameras. It is necessary to have the ability to seize the moment, to detect valuable information and quickly record and transmit it.

From the beginning, this war has been about poor-quality images. By the way, even before the full-scale invasion, I discussed with my colleagues what equipment is better for war photography, digital or film. At that time, I said that a high-quality digital camera is more reliable, and I would take one with me if I went to war. And I did. Initially, I carried my heavy camera around, but it was cumbersome. Imagine you have a weapon and a big camera with all the gear. That’s why the best camera is actually the one that’s in your pocket. The phone replaced everything. It’s these low quality images that truly reflect this war for me. They are all taken quickly, with lousy exposure, because you are constantly running, everything shakes, even if it’s not a combat situation you need to react to circumstances quickly. You’re always shooting in bad light; there’s no time to point the lens or set it up.

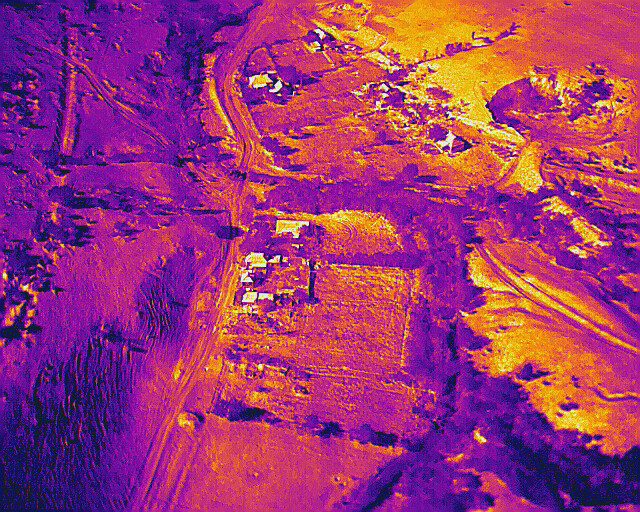

KI: Today, looking at drone images and documentation from thermal imaging, I think about how these technologies are influencing visual culture. I understand the importance of drone and satellite photography, but for me it has a colonial nature and represents the power associated with the desire to conquer with the eye a territory that cannot be seen from the ground.

KP: I agree; this is a fascinating observation. Do you know the Deep State Map? This is a map that shows in real time how our troops are advancing and retreating. Its data is based on various official and public sources. There’s a disclaimer on the map requesting people not to use it for creating evacuation corridors since the data may no longer be accurate. Events at the front can unfold very quickly and unpredictably. But overall, this is an exciting map for me. When you look at Ukraine on Google Maps, it fits easily on a phone screen. It seems small and controlled, it can be zoomed in or out. But when you sit in a posadka [a line of trees near the road, planted as a barrier against weather and pollution], by controlling the drone—and Russians sit across, say, three such posadka—you understand how huge our country is, and if enemies are located in that territory, then they control that part of the land.

When the drone rises to five hundred meters, it becomes like a Google map. And then, the perception of the territory and land changes again. The distance between each liberated or temporarily occupied village or city is enormous, if counted by walking—there are places where you have to travel on foot so that the enemy cannot detect you. This visual reduction of the gaze had a significant impact on me. I started to look at our country differently. I had no idea it was so big and so beautiful. And one’s sense of distance changes significantly. For example, before, you could drive from Kyiv to Odesa on the highway in six hours. However, now you travel in the Mykolayiv region on a terribly broken road in a car with a dented front chassis, and this short section that used to be covered in an hour suddenly stretches to four hours.

Liberated Kherson Oblast, Ukraine, drone investigation, 2022.

KI: When I think about the photos on social networks, I remember the online flash mob that happened after the Bucha tragedy. Twitter users posted two images, one a picture of a dead person and the other a picture of themselves, and they titled it “I am that dead person” or “I might be in that image.” The photograph ceases to be just a photograph; it becomes something else.

KP: Yes, some coincidence or coexistence plays a significant role here, but maybe I am wrong.

KI: I think coexistence becomes essential. It is clear that everyone has their own experience, but still, through photography, the images of war appear to us in common.

KP: Again, the internet has great power. The new film based on Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, recently released on Netflix, has a moment when the soldier returns home, and no one knows anything about the war. The milkman delivers milk, and everyone lives as if there is no war. And this soldier had several friends who died in combat. In contrast, when I had a week off and returned home, my wife told me about the army’s new 155 millimeter guns. I asked how she knew about them, and she said that one country gave them to us, and another supplied some other arms. She knows even more than I do, even though I’m at the front. It is definitely a common war for us because everyone participates in it in one way or another and knows what is going on. People are involved by supporting the army, donating things, developing technology. Fortunately, we live in the twenty-first century, where knowledge has become much more available.

KI: Is there even time for photography during war?

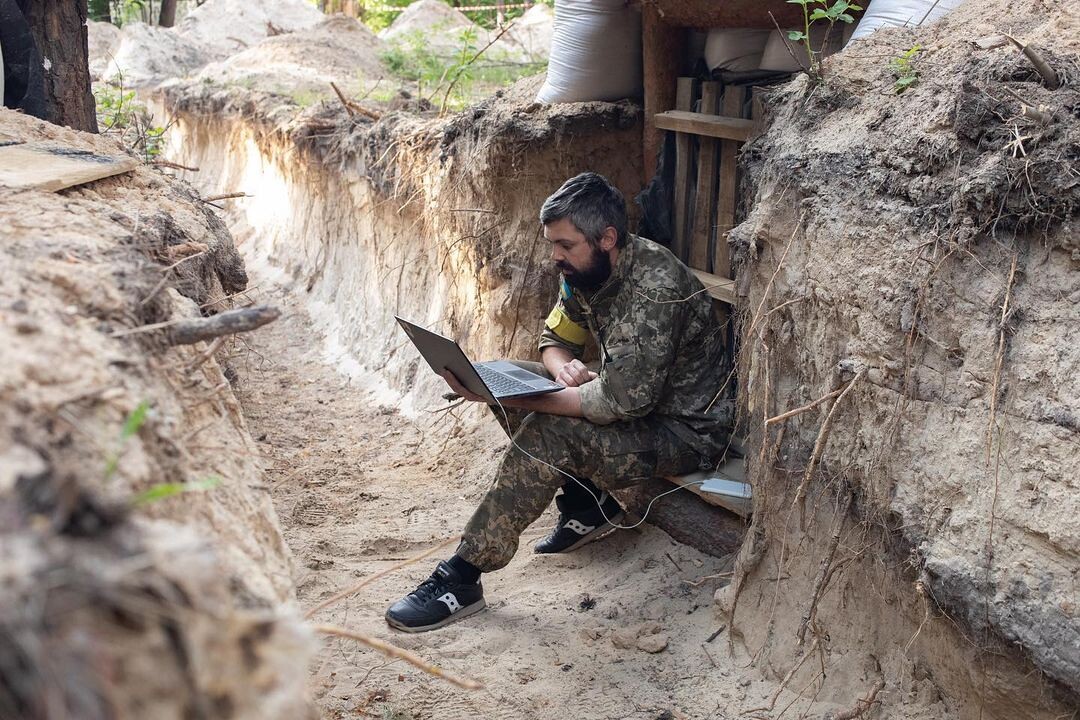

KP: Everything is possible. But of course, it’s hard to predict anything. Even this interview was postponed several times. But in this space, no matter where you find yourself, there is always an interest in photographing what’s around. A colleague of mine in our battalion is a public intellectual. My photographs of him at war will be helpful in his communication and career. My background in photography is in political reportage. But currently, I am thinking of a documentary project combining the theme of food—which is very important at the front—and weapons. I was struck by the sight of old Russian armaments, sometimes even rusty weapons.

KI: Are there specific rules about filming—what can and cannot be filmed, what is ethical in war and what is not? Of course, shooting positions cannot be film.

KP: Right—tactical positions cannot be photographed, nor can the faces of people who do not want their picture taken. But in general, I avoid photographing people in war, although I like this type of photography. The exception is if they ask. But I do not display such photos anywhere.

As for ethics, this is definitely a personal issue for everyone. For example, I cannot film private things in a private apartment. Let’s say that I see something I think would make a beautiful composition, like when a man kisses his wife in a war zone. Often people are ashamed of their emotions, and I find it inappropriate to pry into someone else’s intimate moment.

KI: Do you see much of this in the liberated territories? I mean the shame of emotions.

KP: In the liberated territories, yes. There is complete ruin there. You look at things, and you can guess the fate of the people who lived there. For instance, once we sat through a shelling in an abandoned house, which someone had ransacked. All of us soldiers huddled in a room near the entrance and took cover. While hiding there, I noticed on one of the walls a photo of a handsome man wearing a suit, and the photo was decorated with New Year’s tinsel. Apparently, this house had been captured back in February. The family had no time to clean up the tinsel, they were in a hurry to escape. These small objects or decorations, which usually indicate happiness or joy, in those circumstances appear absurd and chaotic. There’s a lot of emotion in these little things. The military is also emotional and vulnerable, but this is not usually portrayed by the media.

KI: During Soviet times, propaganda made the image of the soldier uncompromisingly stubborn and heroic. Undoubtedly, today’s portrayal of the Ukrainian military man is also about heroism. Still, it also conveys the sense that this person can be vulnerable, that he is not only a soldier but also a father, husband, history teacher, or a musician …

KP: No doubt one of the challenges for our society will be how to live with this military experience after the war. How to learn to live with each other, having had different experiences. Not to give in to prejudices, fears, or gender stereotypes but to build mutual relationships on the basis of a respect for what each person has experienced during this time.

KI: Were you previously interested in military photography? Did you follow how Magnum and Life covered other conflicts?

KP: Yes, I was interested in this and thought about becoming a military photographer. I followed the work of Maksym Levin [1981–2022, a Ukrainian photographer who tragically died at the beginning of the full-scale invasion in Kyiv Oblast], who had documented the war since the spring of 2014. But on February 24, I realized I couldn’t do anything with a camera. I was not protecting myself, my family, or my country with it. I felt that I needed to be more a person than a photographer at that moment. Some people are so passionate about photography that they sleep with their cameras, but that’s not me. I realized that my value would be in something other than photography. Although I now look at my decision differently: it’s also possible to report from the front for agencies and to tell people’s stories in order to show what’s happening in Ukraine. It is essential to show the realities of hunger and genocide and other horrors so that it never happens again. Yes, some people aestheticize the ruins, and others criticize such approaches. But if it weren’t for photography, it would be difficult to learn about the suffering of people far from one’s own home.

Dr. Anton Drobovych, head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, giving a speech to Ukraine House Davos, May 23, 2022. Photo by Kostiantyn Polishchuk. Digital image.

KI: What is your opinion on the aestheticization of the ruins?

KP: That is a good question. The images of a cataclysm can help spread information about it, which is positive from an educational viewpoint. For example, Eugene Smith’s most popular photograph is the one from Japan of a mother washing her daughter who is suffering from a then-unknown disease caused by industrial pollution [Tomoko and Mother in the Bath, 1971]. This is an iconic image, stunning and terrible at the same time. The image was published in Life magazine and spread worldwide; the public learned about this story from the photograph.

KI: There is always a choice of whether to document these horrors and, if yes, how to tell the story. Is there currently a discussion among Ukrainian photographers about what is ethical? Because as far as I’m concerned, filming the war as a Ukrainian photographer is one thing, and filming the war as a Western photojournalist is another. Media corporations have prejudices about what should be in the frame.

KP: I absolutely agree. Foreign photographers who come to Ukraine to document the war treat this experience as just another war. For them, this story has nothing to do with their personal lives. But look at how Ukrainian military photographers depict the war—for example, Yevhen Maloletka, whose photography is intense and emotional. His images evoke different feelings and raise complicated issues; but they are also banal, even the visual language he uses is simple and metaphorical.

Some business offices have aestheticized photographs of war hanging in them, and people enjoy this abstract, ruined beauty. But surely no one would hang a man swollen from hunger in his office.

I will mention another example: Oleksandr Glyadyelov’s exhibition at the Dovzhenko Center in 2020, for which he received the Shevchenko Prize [the main state award in literature, journalism, cinema, theater, and visual arts, named after the iconic writer Taras Shevchenko]. His series “Carousel”—a collection of documentary images from recent decades—is very expressive, but in the Ukrainian photographic community there was a discussion about whether one should put together images of children and the military because this is such a taboo topic. Some people don’t want to imagine that these children could later go to war too. So this is also about vulnerability.

KI: We discussed the ethics of photography and working in a military context. I often ask myself how I should talk about the war and how I should work with my own experience and the experiences of others. In particular, I wonder how to speak about loss, how to come to someone else’s house that was destroyed.

KP: This is important. I know that those who have lost their homes are annoyed by “tourists” and people who walk around their ruined apartments. Some people even take pictures of themselves showing off against the background of ruins. I try not to photograph destroyed houses and people’s personal belongings. There is the concept of a war trophy. But if you remember, there was an interview with a female Ukrainian sniper who said that her fellow soldiers never touch personal things; weapons or ammunition can be taken as trophies, but not the private belongings of civilians. Nothing personal. That’s why I never take photographs of those things either. I cannot imagine how it would feel to have your house destroyed and then see people rummaging through the ruins, looking at your photos, underwear, and clothes. It’s terrible, in my opinion.

KI: You talked about food, and people definitely leave food behind in the houses. For example, they leave food on the table when they barely have enough time to pick up their things and run away from the shelling.

KP: I was thinking about a series of images with these personal items. Such an exhibition could garner a large audience in Ukraine and abroad. Let me go back again to that house that I mentioned before. This home impressed me a lot. A prosthesis was lying on the floor, so I realized that an elderly person lived there. I saw insulin syringes everywhere. Obviously, the person had diabetes. The scattered things I saw there told a story, and it became terrifying. But, as I said, I do not take pictures of private belongings.

KI: You also said that photography helps to tell about the horrors so that they don’t happen again.

KP: If I thought that history could be understood before the war, I see now that the Soviet myth is different for everyone. The Russians fight as if they have not heard of history, as if they do not know the experience of the Second World War. They reproduce many symbolic gestures, for example, attacking at five in the morning, just as Germany did.

History played a different role for me: I was told at school that if a war broke out, one should defend one’s land. I never wanted to join the army, and after completing my master’s degree, I went to graduate school and started working on my dissertation. But when the full-scale invasion began, I decided to join the territorial defense.

Frankly speaking, I am scared that there are still a large number of people who fall for simplified narratives. To understand history, you need to be interested in it and read it; it possesses intellectual layers. But of course, no one is immune to populism. Still, I hope that now and in the future, there will be people who will tell the stories that need to be told and will not be afraid of layers and complications.

Kostiantyn Polishchuk, Untitled. Digital image, 2022.

KI: Does your education as an anthropologist help or hinder you in the war?

KP: It helps because I see things that others don’t. The army is not at all the romantic place that it appears in the media coverage of military forces, especially the handsome soldiers that are presented in social media. It is a complex structure, and it has many complex processes.

KI: When we planned the interview, you said that I should come in a month if you don’t die. So how do you live with the understanding that you may not come back home?

KP: I think I made a decision for myself when I came to the military center on February 25, because on February 24, there was a long line of volunteers, people like me, and it was impossible to get inside. I talked with my wife about what to do, gathered myself, and left. I said goodbye to everyone, as if for the last time. I had no answer as to why I was doing it; it just became clear to me that it was necessary. I remember in March when Russians came closer to the city of Brovary, on the outskirts of Kyiv, and I was on the Left Bank of Kyiv. I remember my comrades calling their wives or lovers, sometimes both; they were saying goodbye to them. And I understood that I had already said goodbye as soon as I left the house. Now I’m surprised every day that I’m still alive. My friends and colleagues are dying, and death seems to be getting closer and closer. But I don’t know how to react to it; I can’t run away from this death anymore; I have to play this game with death to the end. My wife is probably already tired of crying. If I die, I won’t care. And if not, that’s good; an exciting life will likely begin. For instance, I would like to travel again. But then I think, what will I do when I hear a Russian at an exhibition in the Louvre? Honestly, I don’t hate or want to kill them, but I don’t want the shared air to touch me. I want them to live in their own prison, in exile. I want them to finally realize what they have done and what their army and president have done. Let them think about what it’s like to live in anticipation of death, seeing its specter every time. Because waiting is the worst.

KI: I have one last question. There is a story of a soldier who has worked with drones and now dreams in the colors of thermal images. Has this happened to you? What are your dreams about?

KP: My answer is not very interesting. I rarely have dreams. Or I rarely remember them. When I do have dreams they are usually whimsical to me, so there is nothing to tell. Definitely not through a thermal imager.