I ran away into the dark, laughing so hard I feared I might rupture myself … mugged by an invisible man!

—Ralph Ellison, Invisible ManTo reconstitute the community, Black radicals took to the bush, to the mountains, to the interior.

—Cedric J. Robinson

The paradox of Ralph Ellison’s legendary 1952 text, Invisible Man, is that the African American narrator begins with an exclamation of existence through concealment: “I am an invisible man.”1 This phrase revises the act of thinking, or rather, speaking oneself into being, even when one is rendered invisible. Ellison’s protagonist begins at the end, speaking from a hole in which we find him. From a position of boundless darkness, boundless darkn, boundless dar,2 or more precisely, in a hole, Ralph Ellison’s protagonist echoes an internally oppositional character. The character is abstract, in that he is captured in fiction, but he is actualized in his alignment with the material realities of African American existence: black materialism. Ellison’s narrator practices evasion: “In my hole in the basement3 there are exactly 1,369 lights … the older, more-expensive-to-operate kind … An act of sabotage, you know.”4 A site for subterfuge, the basement is symbolic of obscure black radical action. Ellison’s is a hero paradigmatic of the performative act of darkness-in-darkness, becoming darkness-as-darkness: a black agent in a hole. This double performative of advance and retreat (although the main character starts and ends in retreat, the narrative follows with a promise of advancement) demands we investigate the promise of black peoples withdrawing into a hole—into obscurity, invisibility, non-being5—as a necessary point on a continuum of black resistance. This essay seeks to interrogate the ways in which capitalism’s coercive power is challenged by creative dark energy; how black radicalism advocates tactics of advance and withdrawal.

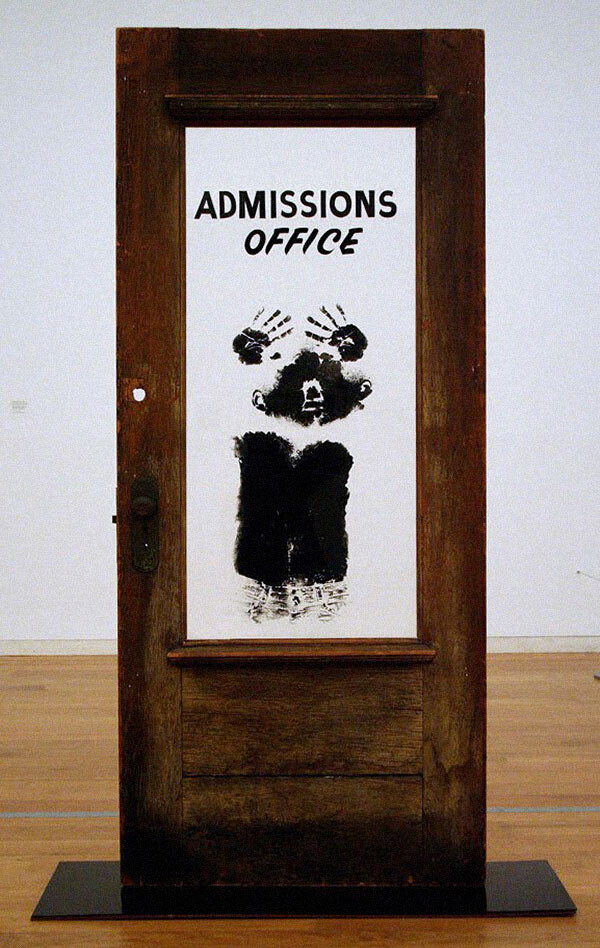

David Hammons, The Door (Admissions Office), 1969. Wood, acrylic sheet, and pigment construction. Copyright: David Hammons.

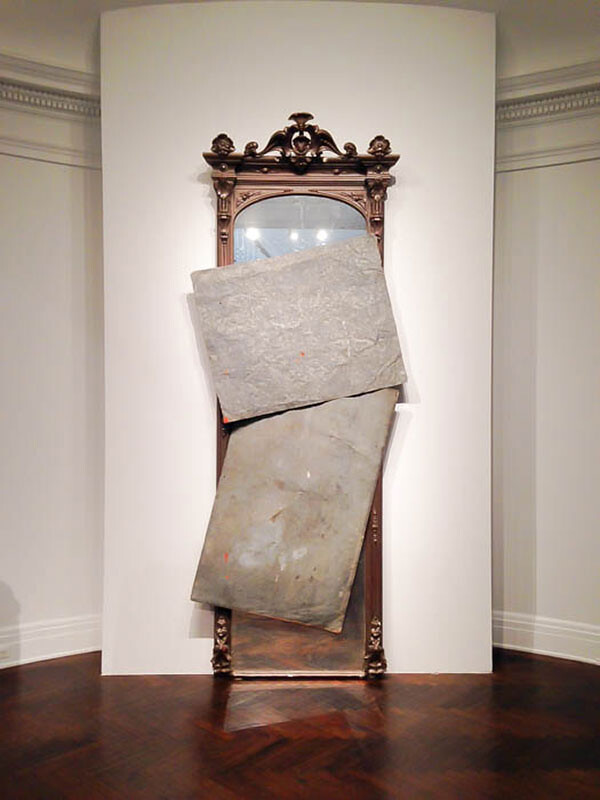

Echoing Ellison’s protagonist speaking from the hole, the American artist David Hammons presents three objects: Untitled (2014), Bird (1990), and The Door (Admissions Office) (1969). Untitled (2014) is a mirror with ornate plaster frame, consuming approximately 128 ½ inches in height and 52 inches in width. Obstructing the mirror’s view are two vertically stacked sheets of galvanized steel; they appear to be nailed to the plaster frame. Untitled’s initial joke on exclusion is accompanied by another work’s confrontation with luxury in the trope of flight. The second object, Bird, presents white paint competing with the encroaching rust of time. An ornate base supports a blossoming, spindly, spear-like torso crowned with an almost linear contour of a three-dimensional fleur-de-lis in flat relief. Within the contours of the crown delicately hangs a basketball and bird feathers immersed in an echolalia of densely woven wires; the wires psychotically shadow the ball’s form. The third object completes the lineup. Oh, hell, it’s a door. Sigh. The Door (Admissions Office) consists of one of those older administrative doors. You know, a scratchy, wooden frame, surrounding foggy or sandblasted glass. In a performative fashion it announces its purpose with the painted black text “Admissions Office,” beneath which we see the imprinted splat of a pair of hands, face, torso, and pants from crotch up, again in black. Developed in the shadow of black folk traditions, these works by Hammons engage the spectator in a series of tricks and games. Through considering the evasiveness (fugitivity) of these works—they paradoxically resist capture, as they enact deception and deadpan humor—we can think about critiques of racialized class; the aestheticization and exhibition of leisure as wealth; the possibilities of a base/black materialism that dissolves class in race; and a continuation of the black radical tradition as established during slavery. Furthermore, Hammons’s black aesthetics absorb, display, rehearse, and reinforce Ellisonian maneuvers of advance and withdrawal in a critique of economies internal and external to black social life. Ellison’s lyricism of blackness as “most-black” reverberates retreat towards a hole. It is from this protective, performative position that Hammons enacts a strategy of darkness-as-darkness. An excessive radical blackness! Let the congregation shout:

That blackness is most black, brother, most black …6

David Hammons, Bird, 1990.

In his works, Hammons scripts the disruptive act: the advancement and retreat of economies. His labor reflexively lacerates an anticipatory twentieth-century white avant-garde who thought they were original and “irretrievably out.”7

Hammons, by way of black radical lineage, speaks out:

We been done that.

French literary theorist Georges Bataille’s materialist lens might expose the darkness—Hammons’s hole/hull, the artist’s deployment of past aesthetics—as a critique of black social life. This resurrection of past creative modes, woven through black artistic, vocal, and literary expression, brings up significant topics like labor and leisure, the black radical tradition, and racial capitalism—all of which centralize certain epistemologies while shadowing others. What I hope to show are some possible criticisms and critical tactics that might be available in Hammons’s work, starting, like Karl Marx, from the bowels.

The intestinal tract is a musical chamber. Mother Nina’s lyricism voices black possibility:

In the dark / Now we will find8

Where else would the dense material we hope to consume in this text be most appropriately metabolized?

Bataille answers from within Marx’s shadow:

He [Marx] begins in the bowels of the earth, as in the materialist bowels of proletarians.9

Following Shakespeare and Hegel, Marx resurrects, re-dresses, and rehearses the metaphor of the “old mole,” when, in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, he praises revolution:

But the revolution is thoroughgoing … It completes the executive power, reduces it to its purest expression, isolates it, sets it up against itself as the sole target, in order to concentrate all its forces of destruction against it. And when it has accomplished this second half of its preliminary work, Europe will leap from its seat and exult: Well burrowed, old mole!10

From a bird’s-eye view, Marx’s anticipatory celebration re-presents the proletariat, the folk, as a revolutionary mass, springing to radical action in the face of executive, economic bourgeois hegemony. Marx’s imaginary animates the base class as a “seasoned” mammal.

Recovering the aged metaphor in “The ‘Old Mole’ and the Prefix Sur in the Words Surhomme [Superman] and Surrealist,” Bataille references Marx’s digestive track when exploring his “old mole.” Bataille portrays the political form of high versus low as a conflict between the eagle and the geriatric mammal, the animals representing Marx’s class struggle. As an ornithologist, Bataille proposes the eagle as the figure of the apex: “Not only does it rise in radiant zones of the solar sky, but it resides there with uncontested glamour.” The eagle “is identified with imperialism, that is, with the unconstrained development of individual authoritarian power.”11 To Bataille, the eagle signifies hegemonic capitalist imperialism. He continues to align this sign of surplus with violence, stating: “The eagle’s hooked beak, which cuts all that enters into competition with it and cannot be cut, suggests its sovereign virility.”12 While the eagle represents advances to power—the sur of surhomme as super—Marx’s old mole assumes a radically counter-position: “Brought back to the subterranean action of economic facts, the ‘old-mole’ revolution hollows out chambers in a decomposed soil repugnant to the delicate nose of the utopians.”13 Marx’s old mole is representative of the revolutionary surge of the masses from a subterrestrial locale: lower than the eagle, lower than the ground, a darkness within darkness, that which is underfoot.

[Sing!]14

So low you can’t get under it

So low you can’t get under it]

[html So low you can’t get under it15]

[html

Beneath the sign of the eagle reverberates the historical relationship between imperialism and violence as unified in capital. While the old mole, much like Ellison’s protagonist, develops “acts of sabotage” in the dark—1,369 lightbulbs consume extensive amounts of energy—the eagle implicitly performs a wholly counterproductive act of negation in and against its right from above. The beak—which cuts all that enters into competition with it and cannot be cut—severs the life force (spirit) from the masses. This is possibly resurrected by David Hammons.

We hear Aretha Franklin haunt in absentia:

I’m getting the spirit in the dark.16

By severing this spirit, the eagle is surely maneuvering towards death. Might the black middle-class mirror the similar advances of Bataille’s eagle? Deploying black sociologist frameworks, what foresight might precede Hammons’s performance?

Grounding inquiry in the “eagle and old mole” metaphor illuminates the relation between the black middle class and the masses respectively. Sociologist E. Franklin Frazier provides insight into the act and consequences of cutting performed by the black bourgeoisie. Frazier’s controversial and creative analysis of racialized class, from the tail end of slavery to the mid-twentieth century, fore-shadows Hammons’s operation with base materialism, as he attempts to suture the wound. Frazier-as-preface is an anticipatory blackness (fore-shadow) that demands we start beneath the bottom.

Starting from the base—underfoot—allow us to comprehend how the bourgeoisie/mass dialectic is cloaked in race. Frazier explores racialized class in his seminal 1957 text Black Bourgeoisie. Here he challenges a contentious understanding of the absented racial contours of Marx’s class struggle; the invisible realities of the entangled signifiers “race” and “class.” Frazier initially addresses a cultivated black bourgeoisie striving towards social mobility, not by property, but by ancestry and education: “At the top of the social pyramid there was a small upper class. The superior status of this class was due chiefly to its differentiation from the great mass of Negro population because of a family heritage which resulted partly from its mixed ancestry.”17

The eagle reflects black mobility as: imperialism, absolute power, and crowning the world market—at least the black American world market. In seeking the eagle’s perch, the black bourgeoisie’s desire to be an elevated class is only possible through miscegenation. This entropic promiscuity constituted social mobility during slavery. Frazier continues his definition of the black middle class when discussing academic education, emphatically proposing that “education has been the principal social factor responsible for the emergence of the black bourgeoisie.”18 Education tethered to sexuality was a principle motivation—black mobility linked mixed ancestry and education—from which the black bourgeoisie emerged. The telos of this desire to reach the apex of the social pyramid is the black bourgeoisie, with whom comes “access/success.” How does race inform a striving towards access/success?

Striving for success rendered the black body hyper-flexible: able to bend, move, and adapt by most means necessary. Because Marx rarely witnessed race, he couldn’t anticipate the malleability of darkness. Marx sees the bourgeoisie emerging from the feudal order as a merchant class seizing the means of production, whereas Frazier sees a racialized middle class emerging from slavery towards negation; seeking access by way of illegal (sexual) unions. Anti-miscegenation laws remained on the legislative books in the United States until 1967. Teaching slaves to read was punishable by death. It is in this sense that the black bourgeoisie is motivated by death, or if nothing else, at least by desire. How is the mortal motility in the elevated status desired and appropriated by the black bourgeoisie? Is it possible to exorcize the destructive drives constitutive of the black middle class?

Fearing annihilation, Marx’s “old mole,” like Frazier’s “black mass,” retreats to the hole. In this gap, Ellison’s radical hero saps the system’s energy. Although isolated in the text, he represents a greater marginalized group: the black masses. What motivated opposition to the black middle class? How were the black masses constituted by a class above? From afar we hear the irretrievably out Funkadelic echo:

[Sing!]

So high you can’t get over it]

[html So high you can’t get over it

So high you can’t get over it19

Frazier establishes that the masses exist in opposition to the black bourgeoisie. As quoted above, Frazier states that “the superior status of this class was due chiefly to its differentiation from the great mass of Negro population.” Frazier sees the black middle class as emerging from the masses, out of the dark. If the “old mole” is the base upon which the bourgeoisie is erected, enframed20 by Frazier’s sociological rigor, his “black mass” as “old mole” establishes the dark horde as the very same ground from which the black bourgeoisie seeks to flee, and ultimately stand. At stake is an urgent understanding of the utility of the black masses as the ground from which the black eagle assumes flight; the black masses as earth; as the bottom; as the foot. In this way, Frazier makes the masses irreducible to the elevated middle class.

Base matter is similarly operative in Hammons’s work. If he is to relate his aesthetic ambitions to a base/black materialism by way of black earth, then essential to his project is how his labor might operate through and with matters that are a-foot. Furthermore, if the black middle class emerges from a dark ground, and the black bourgeoisie is motivated by social appetite, can this speculative syllogistic structure connect the base with desire?

The black bourgeoisie’s desire to escape the shadowed mass is precisely what motivates its economic liberation from the black masses. Frazier defines collectivity among the black bourgeoisie as being formed through evading tradition, and as a bourgeois response to cultural roots. The dark majority of the mass represents a folk tradition from which the black middle class strives to escape. The black bourgeoisie aims towards a symbolic death. Frazier identifies what he calls “one of the most important consequences of the emergence of the black bourgeoisie”:

namely, the uprooting of this stratum of the Negro population from its “racial” traditions or, more specifically, from its folk background. As a result of the break with its cultural past, the black bourgeoisie is without cultural roots in either the Negro world with which it refuses to identify, or the white world which refuses to permit the black bourgeoisie to share its life.21

This symbolic death, established by severance from a cultural heritage, is echoed by the metaphor of the eagle. While the eagle’s beak cuts, the masses as folk, as old mole, as developed through Hammons’s critique of black leisure, push from the margins. They push against typical constructions of high/low social forms. In his controversial but oft-cited essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Clement Greenberg offers one such narrow classification:

There has always been on one side the minority of the powerful—and therefore the cultivated—and on the other the great mass of the exploited and poor—and therefore the ignorant. Formal culture has always belonged to the first, while the last have had to content themselves with folk or rudimentary culture, or kitsch.22

While this exclusionary “logic” has met many criticisms, Greenberg’s elitism aligns with black capital’s fugitivity: a sprinting advance from the ground. The results of Greenberg’s position include privileging certain epistemologies and simultaneously shadowing others. Can this maneuver be read against the folk in relation to Hammons’s position as darkness? How does Hammons’s use of folk culture challenge and declassify modernism’s economies? It is in the literal refusal of access, and deadpan deception, that Hammons echoes the black masses’ aesthetics. Retreating to the hole, the artist continues his conspicuous presentation with Untitled. His is a steel defense against representation. The Negro spiritual of fugitivity is instructive, hear:

Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus!23

This mid-nineteenth-century song, composed by slave Wallace Willis, encodes fugitivity. “Steal away” hides a message for slaves to flee bondage. The coded couplet “steal/steel” calls for liberation. Willis croons about fleeing bondage, whereas Hammons enacts the freedom and promise of control and access. The metal sheets barricade against any access to direct reflection. A conversation between the two works speaks the black masses’ resistance to power: “If you won’t let me go then, I sure ain’t letting you in now.” The “you” speaks towards the white slaveholding class, as well as those black capitalists who severed ties with the black masses, benefitting from the trafficking of dark cargo. While this exchange of black bodies reflects the economic flight of black eagles, Hammons’s work ain’t just a challenge to black economic flight, but also to the higher structure that governs its aim: to become a bourgeois leisure class.

Employing Hammons’s work as a critique of the subject of black leisure seems to only operate through a grounding in two central radical materialisms: base and black. What we mean to propose is a collaboration of “base” and “black” as “dark.” Put another way, there might be parallel elements connecting base and black materialisms, such that they might be unified under the sign of darkness-as-darkness: the black agent in the hole. To enact such a tactic, we must briefly define base and black materialisms.

According to Bataille’s words in Visions of Excess, in conjunction with theorist Benjamin Noys’s notion of base materialism, base matter recognizes and employs all materials, both high and low. Noys writes: “The ‘logic’ of base materialism is that whatever is elevated or ideal is actually dependent on base matter.”24 The symbiotic relationship between high and low is further extended by expressing the idea that the purity of the elevated ideal is contaminated by its connection to the base. In this sense, base matter is initially defined as the low within the dialectic, as the high separates itself from the “lower order.” The eagle flies again. Both Bataille and Frazier echo Noys’s thoughts on base materialism’s initial dialectic. We see this inchoate urge to maintain the binary in Bataille’s “The Big Toe.” Examining social symbiosis, he rhetorically exposes the high’s dependence on the low by way of the human foot’s primary unit: the big toe. As the ideal, or high, is an elevated position, Bataille places specific emphasis on the utility of the foot: “The function of the human foot consists in giving a firm foundation to the erection of which man is so proud (the big toe ceasing to grasp branches, is applied to the ground).” As base matter, the big toe’s role is to erect and stabilize man. However, that which is elevated must distinguish itself: “But whatever the role played in the erection by his foot, man, who has a light head, in other words a head raised to the heavens and heavenly things, sees it as spit.”25

Imagined as spit, the big toe as base matter is isolated from the ideal, constitutive of that which is vulgar, vile, violating. Ain’t base mass dark? It is also that which makes “man into man.”26 As such, the big toe—base matter—grounds the high/low opposition, grounds humanity. The consequence of this foundational position is the emergence of third position, exceeding the confines of dialectical processes: one that supports and destabilizes the dialectical Marxist class struggle; one that, as base matter, interminably evades capture within any dualistic structure. Bataille’s base materialism is the eagle’s detachment from base matter as a support. This is a severance that is a drive towards death. Noys “resolves” this in part. “Base matter is what we called the ‘third term,’ underpinning and undermining the oppositions which structure philosophy, it is an irreducible remainder.”27 What Noys’s “third term” gets at is the possibility of things not fitting into the dialectics of discourse, exceeding its circumscription. As surplus, Noys’s “third term” speaks beyond and beneath the conventional binary structure. This revelation complicates the argument. Initially high/low, in which low was base, now both high and low are separated from the bottom, thus establishing “base” as Noys’s third possibility. Existing beyond the confines of the upper–lower dialectic, base materialism challenges both positions. Is this excessive “third term” operative in Hammons’s work? If so, what is its utility? Will it force a collapse?

David Hammons, Untitled, 2014. Photo: Osman Can Yerebakan

It ain’t just the black bourgeoisie seeking flight. As base materialism evades capture, black materialists’ aims follow a similar path. This path is most pointedly developed in Black Marxism, in which political scientist Cedric J. Robinson explores the failures of Marx’s analytical tools to recognize the racial components of capitalism, ultimately challenging the claim of a universal proletariat. Listen to how Robin D. G. Kelley, professor of American History at UCLA, summarizes Robinson’s project in the “Foreword” to Black Marxism: “This book is, after all, a critique of Western Marxism’s failure to understand the conditions and movements of Black People in Africa and the Diaspora.”28 This deficiency in Marxist analysis is what precisely aligns Black Marxism with an invisibility foundational to base materialism. Marx’s disavowal of race as central to capitalism places all racial materialisms at the bottom, in the dark, as dark. Kelley, by way of Robinson, broadcasts from a hole. Refusal to be captured is black radicalism. Such refusal first emerged as tactical resistance instantiated in the form of acts of insurrection and fugitivity by black communities during slavery. By 1727, des Natanapalle, a Louisiana maroon village composed of Native Americans and blacks, seen as a threat, was annihilated through internal betrayal. Aligned with this tradition of resistance, Robinson voices from the dark, makes darkness speak: “Black slave resistance naturally evolved to marronage as the manifestation of the African’s determination to disengage, to retreat from contact. To reconstitute the community, Black radicals took to the bush, to the mountains, to the interior.”29

A sense of strategic, resistant retreat that is the black radical tradition is echoed in Hammons’s haunting withdrawal. Note how Robinson slyly whispers that the aim of retreat is interiority. Interiority is darkness-as-darkness, is blackness as base, is the hole. What is visible in Robinson’s racial Marxism is not only the comparative relationship of blackness with baseness—we might return to the “lower order” Kelley cites in Robinson’s terms—but the potential blind spot in Marxist critique: the dark spot, the racial mark, the base, that fore-shadows Marx.

What is required in thinking the encounter between base and black matter? Where … what edges are implicated in this counterintuitive move towards this materialist collapse? Echoing the eagle’s violence while in the mole’s hole/hull, this thinking requires contact between Ellison and Hammons: in the dark. In the dark-as-dark, where folk aesthetics meet a surreal narrative, where detritus is repurposed in the form of a black Bildungsroman. Nina Simone’s lyricism echoes through the bowels:

[Sing!]

In the dark

Now we will find

What the rest

Have left behind30

Hammons picks up the beat hear, locating promise in the dark. From “What the rest / Have left behind,” Hammons strengthens the force against the eagle. Bataille anticipates Hammons when voicing his thoughts on Marx’s old mole, as quoted above: “The ‘old-mole’ revolution hollows out chambers in a decomposed soil repugnant to the delicate nose of the utopians.” In these chambers the artist resurrects past aesthetics of the black masses—salvaging materials tossed out by the bourgeoisie—and presents them anew. All the elements of labor we’ve lined up in our hole wear-the-wear of being everywhere: the door of The Door is scuffed all about the wooden frame; the persistent flickers of rust defeat the white paint of Bird—oh, well, you fought the good fight; and the cold rust of galvanized steel/steal and shoddy plaster frames Untitled. Maybe this is the sign of a secondary or tertiary class, of which American economist Thorstein Veblen speaks in The Theory of the Leisure Class. Veblen proposes the ideas of “vicarious leisure” and “vicarious consumption” to explore how wealth is displayed in upper-class households. “Vicarious leisure,” he writes, is “performed by housewives and menials”—by the servant class, the class beneath the most elevated class (Bataille’s sureagle). “In this way,” continues Veblen, “there arises a subsidiary or derivative leisure class, whose office is the performance of a vicarious leisure for the behoof of the reputability of the primary or legitimate leisure class.”31

As the primary racialized leisure class, the black bourgeoisie “legitimately” displays its wealth through leisure, and what Veblen calls “conspicuous consumption”: wasteful spending habits to purchase objects that, in their exhibition, display the buyer’s wealth. The black masses might be said to collect the objects and behaviors of an upper class to emulate their status. Morris Day calls from the shadows:

Somebody bring me my mirror!32

While Hammons cannot shut down Day’s demand for visibility, he can offer an alternative economy. In 1983, the same year as Day’s call, Hammons performed Bliz-aard Ball Sale, in which the artist became a street vendor of snowballs, representing the shadow economies prevalent in Harlem and other income-fluid communities. Day’s demand for visibility highlights the radical approach primary to Hammons’s project. Whereas Day requires the shine of new objects, what we see in Hammons is a scavenging, a repurposing more akin to slaves collecting (to hoard is to amass) the master’s hand-me-downs: the objects rendered obsolete by the master, or, for argument’s sake, the black bourgeoisie, as they might be said to act as racial surrogates for the master.

In true base-materialist stance, at this point we should wallow for a moment. Hell … this node might enact the severance displayed by the black bourgeoisie, cutting this text short, fearing it exceeds the discourse’s confines. With no horizon in sight, I mean to suggest here the potential of folk as distinguished from vicarious consumption. Repeating a previous point: David Hammons is not acting vicariously through a higher class, but as a mole, scavenging in the base-as-base to repurpose objects deemed obsolete by the “higher order.” Hammons as black mass, dark-as-dark, dark-as-hell, a black agent in a hole, ultimately exists, at least aesthetically, in the “lower order” Kelley summarized for Robinson’s text. Dragging the castoffs to his basement, Hammons births radicality. Aligning this act with the black radical tradition, Hammons biologically anticipates the impossibility of access prevalent in the work, through a refusal of labor. Fore-shadowing the artist (with black anticipation), Robinson’s words about resistance and withdrawal reverberate towards blackness: “Black slave resistance naturally evolved to marronage as the manifestation of the African’s determination to disengage, to retreat from contact. To reconstitute the community, Black radicals took to the bush, to the mountains, to the interior.”

In true performative stance, Hammons’s labors enact tactics of retreat. Untitled withdraws into darkness with the advent of galvanized steel. A base-materialist gesture of protection—think here of African shields—these industrial sheets reverse the mirror’s logic. Once a site of reflection, his shielding turns logic around and off. David ain’t gettin’ Morris his mirror. Bird, the title of which probably references the white basketball star Larry Bird, employs the language of wire (metallic netting) to “stuff” the ball’s utility. And most appropriately in The Door, the black body is not permitted admission. All signs lead to retreat.

All of these resurrect a black Marxist stance of withdrawal, denial, and protection. This is only one of the slip-the-yoke Ellisonian jokes that one finds in David Hammons’s oeuvre. In true Bataillean fashion (the militaristic nature of the term exceeding Bataille’s spotlights tactics—battalion), Hammons replicates this aim into himself. Witness the old mole’s subterranean activity as destabilizing sediment. Anticipate the earthly consequences of an overactive “digger.” Seeing Hammons-as-mole with a prolific oeuvre, what might the geological consequences of this excessive production be? Returning to Noys’s appositional (third) term, base-as-ground, the result of the mole’s surplus burrowing is the implosion of the ground. Standing on this ground, above the base, racialized class dialectics collapse; the high/low distinction is reduced to dust. Hammons annihilates and revises the old saying: black don’t crack.

Theorist and cultural critic Boris Groys casts a foreboding shadow on the possibilities of radical revolution. Hear how he speaks when questioning the constitutive possibilities of revolution through an analysis of Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square. “Revolution is the radical destruction of the existing society,” he suggests with nostalgia. “However, to accept this revolutionary destruction is not an easy psychological operation.”33

Radical destruction is hard precisely because it maintains no sentimental hang-ups. Groys supports an argument against nostalgia through the ambitions of the Russian and European avant-gardes: “The Russian avant-garde—and the early European avant-garde in general—was the strongest possible medicine against any kind of compassion or nostalgia. It accepted the total destruction of all traditions.”34

Groys rescues his reader from nihilistic darkness when speaking-on the stability of the “destruction’s image.” While advocating an annihilating force for all things art, Groys wins his reader back by br(e)aking the drive towards total annihilation. Why? Because there is something that survives: the image of destruction. “Malevich’s answer to this question is immediately plausible: the image that survives the work of destruction is the image of destruction.”35 While materials can be destroyed, totally decimated, the mere fact that the act (the destruction) survives means there will be a future: promise confirmed. W. E. B. Du Bois, by way of Cedric Robinson, reaches towards temporal promise: “Consequently, we have had a past, we can have a future … Black Sovereignty!”36 Groys prophesizes: “Destruction cannot destroy its own image.”37 Seeing in Hammons, glancing into his darkness-as-darkness, his hole, the potentiality of an overdetermined, underrepresented mole is revealed. The implosion must be televised! Assume it will result in class collapse. As Frazier sutures the black bourgeoisie to the black masses, Robinson anticipates from the base, providing a goal for fugitivity: “To reconstitute the community.” The implosion symbolic in Hammons might offer a possibility of healing beneath the sign of darkness-as-darkness, if only to access the base. B. B. King instructs or maneuvers when defining the blues:

I’m going in the bottom.38

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (Signet Books, 1952), 1.

The repetition and shift in font size is meant to reflect “echo” as concept, progressed through this essay.

Italics added by me for emphasis on relation to base matter.

Ellison, Invisible Man, 6.

The “non” is meant to express the existential endurance of blackness, especially black subjects, in obscurity.

Ellison, Invisible Man, 9.

Nathaniel Mackey performatively voices and reflects this phrasing in From a Broken Bottle Traces of Perfume Still Emanate: Volumes 1–3 (New Directions, 2010), 25. Here it expresses marginalization of black subjects, their reaching for expressions beyond convention, and the logic of creative acts that refuse access.

Nina Simone, “In the Dark,” Nina Simone Sings the Blues (RCA Victor, 1967.)

Georges Bataille, “The ‘Old Mole’ and the Prefix Sur in the Words Surhomme (Superman) and Surrealist,” in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927–1939, ed. Allan Stoekl (University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 32–44, 35.

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, marxists.org, 61 →.

Bataille, “The ‘Old Mole,’” 34.

Bataille, “The ‘Old Mole,’” 34.

Bataille, “The ‘Old Mole,’” 35.

This directive is included by the author to highlight the importance of performing this citation.

Funkadelic, “One Nation Under a Groove,” One Nation Under a Groove (Warner Bros., 1978).

Aretha Franklin, “Spirit in the Dark,” Spirit in the Dark (Atlantic, 1970).

E. Franklin Frazier, Black Bourgeoisie (Free Press Paperbacks, 1997), 20.

Frazier, Black Bourgeoisie, 24.

Funkadelic, “One Nation Under a Groove.”

“Enframing” (Gestell) is meant to reference Heidegger’s use of the term when he explores the role that technology plays in circumscribing events. The term is used in his essay “The Question Concerning Technology.”

Frazier, Black Bourgeoisie, 24.

Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Beacon Press, 1989), 16.

Wallace Willis, “Steal Away to Jesus,” ca. 1862.

Benjamin Noys, “Georges Bataille’s Base Materialism,” Cultural Values 2, no.4 (1998): 499–517, 500.

Georges Bataille, “The Big Toe,” in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927–1939, ed. Allan Stoekl (University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 20–23, 20.

Noys, “Georges Bataille’s Base Materialism,” 501

Noys, “Georges Bataille’s Base Materialism,” 510.

Robin D. G. Kelley, “Foreward” to Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (University of North Carolina Press, 2000), xiii.

Robinson, Black Marxism, 310.

Nina Simone, “In the Dark.”

Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (Oxford World Classics, 2009), 43.

Morris Day and The Time, “Jungle Love,” Ice Cream Castle (Warner Bros.. 1983). While Morris Day’s demand for a mirror is not mentioned in the official lyrics, it is performed in Prince’s movie Purple Rain, which features a performance of “Jungle Love” by the band.

Boris Groys, “Becoming Revolutionary: On Kazimir Malevich,” e-flux journal 47 (September 2013) → .

Groys, “Becoming Revolutionary.”

Groys, “Becoming Revolutionary.”

W. E. B. Du Bois quoted in Cedric J. Robinson, “Du Bois and Black Sovereignty: The Case of Liberia”, Race & Class 32, no. 2 (1990): 39-50.

Groys, “Becoming Revolutionary.”

B. B. King, “Nobody Loves Me But My Mother,” All Blues (Lucas Records, 1999) →.