In 1971, Jarosław Kozłowski and Andrzej Kostołowski conceived of a conceptual proposal that was designed to be universal, prompting extensive East–East and East–West exchange.1 Kozłowski recollected: “Kostołowski and I met very frequently and talked about art a lot, swapped books and so on. The idea of ignoring all the physical barriers and borders which limited contacts was born in a very natural way, as was the idea of using the post to get in contact with various artists around the world.”2 On paper bearing the rubber-stamped blue header “NET,” the pair painstakingly typed out a nine-point statement which they each signed and mailed, from Poznań, in Poland, where they both lived, to more than 350 recipients, reading:

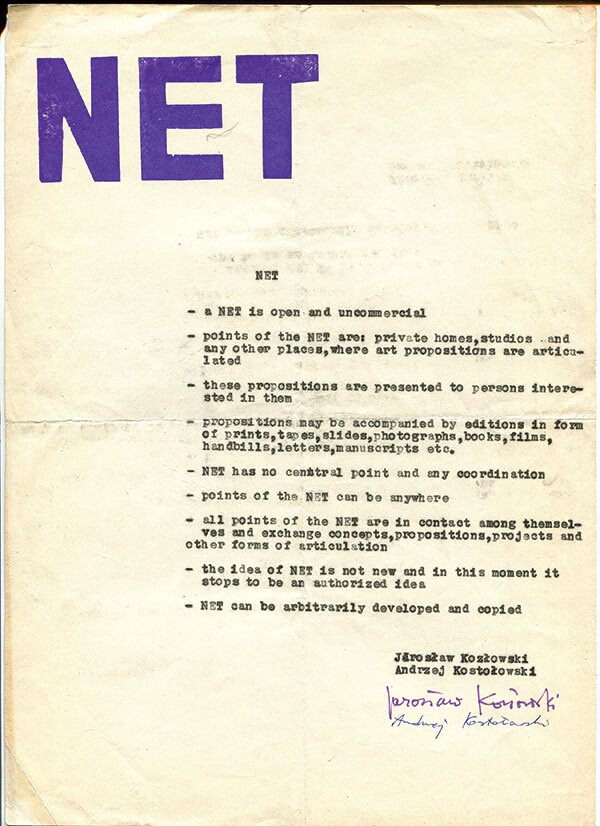

- a NET is open and uncommercial

- points of the NET are: private homes, studios and any other places, where art propositions are articulated

- these propositions are presented to persons interested in them

- propositions may be accompanied by editions in form of prints, tapes, slides, photographs, books, films, handbills, letters, manuscripts etc.

- NET has no central point and any coordination

- points of the NET can be anywhere

- all points of the NET are in contact among themselves and exchange concepts, propositions, projects, and other forms of articulation

- the idea of NET is not new and in this moment it stops to be an authorized idea

- NET can be arbitrarily developed and copied

The proposal was produced in two versions, one in Polish, one in English, and was an open platform to be shared by others independently of its original designers. Initially a nominative exercise—a conceptual artwork that was intended to become a generative principle—it was to be a connector that would bring artists together within the structure of a unifying proposition. Significantly, though, Kozłowski insists that NET “was never a group” and was, above all, “concerned with dialogues between individuals.”3 In addition to announcing a conceptual framework for NET as a type of activity, the mailing also played a crucial role in helping to put artists in contact with one another, for every statement was accompanied by an appendix listing the names and addresses of the “persons invited to be co-creators of NET.”

The long list of recipients consisted mostly of North American and Western European artists. However, a selection of Eastern European figures were also included: from Poland, Wiesław Borowski, one of the founders of Galeria Foksal, Urszula Czartoryska, Ireneusz Pierzgal- ski (Łódź), and Maria Stangret; from Bulgaria, Slatni Boyadgiev (Plovdiv);4 from Hungary, Endre Tót; from Czechoslovakia, the conceptual artist Dalibor Chartny and the artist and visual poet Jiří Valoch (Brno); from the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the visual poet Carlfriedrich Claus; and the Yugoslav artists Janez Kocijančić (Novi Sad), Miroljub Todorović (Belgrade), and Srečo Dragan (Belgrade). Kozłowski would later invite several of those originally on the list to exhibit at Galeria Akumulatory. The original mailing list reveals the limited connections among Eastern European artists at the time, and highlights the degree to which artists remained largely oriented to the West. This not withstanding, NET represented considerable progress in fostering independent connections between artists in the Soviet satellite countries.

Kozłowski explains that “at least to begin with, everyone got the list. Later it wasn’t so coordinated any more. At some point we stopped sending the list. We sent out a few batches of the manifesto with the first list, and then there were appendixes when the list grew, then there were two or three appendixes. But later I stopped sending appendixes because the whole thing became internally generative and there was no longer the need to inform people about it.”5 He stresses that NET was addressed to “artists who were not interested in careers, commercial success, popularity or recognition: artists who devoted more attention to the issue of their own artistic, and therefore ethical, stance than to their position in the rankings, whether the ranking in question was based on the highest listing on the market, or the highest level of approval from the authorities. These artists professed other values, and other goals led them onward, they were focused on art, conceived as the realm of cognitive freedom and creative discourse.”6 The assumption was that such attitudes transcended the ideological frameworks of both really existing socialism and capitalism.

Kozłowski and Kostołowski saw parallels in artists’ responses to the cultural shortcomings of both systems, reflecting that their contacts with Western artists had convinced them that artists there had “attitudes analogous to those we had here,” in spite of certain obvious differences in circumstances. As Kozłowski later put it: “Here, ideology was really related to the system, while over there it was about commerce, institutions, the whole commercialization of art and institutionalization of art that was very present.”7 NET highlighted the common basis of the two systems and parallels between the ways their respective circuits for distributing art were guarded by gatekeepers, whether state-appointed representatives of cultural institutions or capitalist gallerists and museum workers. The ideological criteria of both distribution systems forced artists to try to negotiate certain models which would be rewarded. In both cases, the artist had to jump through hoops and engage in professional networking in order to achieve visibility, confronting a range of bureaucratic and institutional obstacles. NET sought to bypass existing art world mechanisms by proposing a field in which artists could distribute their ideas freely.

The proposal played with adopting an official aesthetic. Kozłowski reflects that the distinctive blue block lettering of the header “NET,” achieved by carving the letters out of rubber, was part of a strategy designed to dupe censors or controllers at the post office into thinking that the letter had been issued by an officially supported organization of some sort, and did not merit closer scrutiny. Their decision to sign the document added to the bureaucratic “look” they sought to cultivate.

The artists also declared that “the idea of NET is not new.” Kozłowski explains: “We wanted to be pragmatic. So we didn’t want to emphasize that it was our idea, as authors—authorship would have interfered,” but they signed the documents because they “wanted to act responsibly.”8

In defining NET as a decentralized, infinitely reproducible scheme for the transmission of ideas to interested receivers, Kozłowski and Kostołowski offered a pioneering theorization of the alternative network. But they were also describing a system that was already in operation, drawing on existing instances of unofficial artistic exchange and sociability. Their statement declared that all such activities were now connected; that all independent initiatives were significant and that everyone acting autonomously in some way was also doing so within the framework of a new, powerful, solidarity.

Kozłowski had deployed the Polish postal system to artistic ends in an early series, Correspondence I-V, anonymously distributing five conceptual propositions in the years following 1968. 9 He explained: “The anonymity of the correspondence piece came out of a desire to avoid authorship and not to construct an artistic identity or a name for oneself—to escape attributing whatever exists in art to the signature.” The mailings contained proposals for participatory artworks, some of which entailed the recipient taking action of some sort upon receipt of the instructions. These included counting grains of sand, making a paper airplane to be signed and thrown out of the window, and pairs of half-photographs mailed to different people accompanied by the name (without further contact details) of the person who had been the recipient of the other half. He had been interested in forming connections that were unlikely ever to be translated into meetings: “If I sent it to Mr X, there was information that the rest of the photograph, which wasn’t there, was in the possession of Mr Y, and Mr Y’s with Mr Z, and in this way a huge circle was produced.” If the proposal was a game that raised questions about the limits of knowledge while courting connectivity, it was not an entirely hopeless case insofar as there remained a chance that the two halves of the image might at some point be reunited. While Kozłowski mailed out at least one hundred copies of each proposal, they were not all sent to strangers: “They were sent to people I knew and to people I didn’t know, whose addresses I took from the phone book … Not necessarily artists.” While he had deliberately conceived of these first five pieces as a form of mail art, he had not considered NET to be a mail art activity: “It was just that the mail was the only possible way to distribute the idea.” One of the earlier mail art pieces had been destroyed by the postal service: “The name of some high-up politician happened to be among the addressees, which led them to be suspicious. To be on the safe side, they destroyed the entire batch of correspondence, which I had carelessly sent from just one post office.”10 He did not make the same mistake with NET and mailed the letters from different post offices. The project ultimately came to the attention of the secret police anyway, though by different means.

Although there were comparatively few Eastern European artists on the first list, those who had been included soon managed to get the ball rolling. NET worked according to a system of permanent recommendation and expansion. Eastern European artists were among the most enthusiastic recipients of the proposal, and many people wrote to Kozłowski and Kostołowski asking to be included in the project, requesting to receive materials and to have their names added to the list. Tót conveyed information to other Hungarians, Chartny and Valoch to others in Czechoslovakia, and so on. There was a sense of urgency about international contacts at this time, manifested particularly strongly by artists in Czechoslovakia, whose conditions had turned from being very open to being dramatically curtailed in a short space of time. When concrete poet Jiří Kocman in Brno wrote to Kozłowski in 1972 to request a copy of NET, he mentioned that he already knew Groh, Štembera, Valoch, and Perneczky. He also summed up the general feeling among these artists: “Communication between us all is very important now!”11 Although a degree of concern with the appearance of the typed copies is clear, the physical copies of the communiqué were not conceived of as artworks: “In a sense the objects and works are peripheral. But it is only natural that the registration of the idea—the proposition—becomes the language of exchange.”12

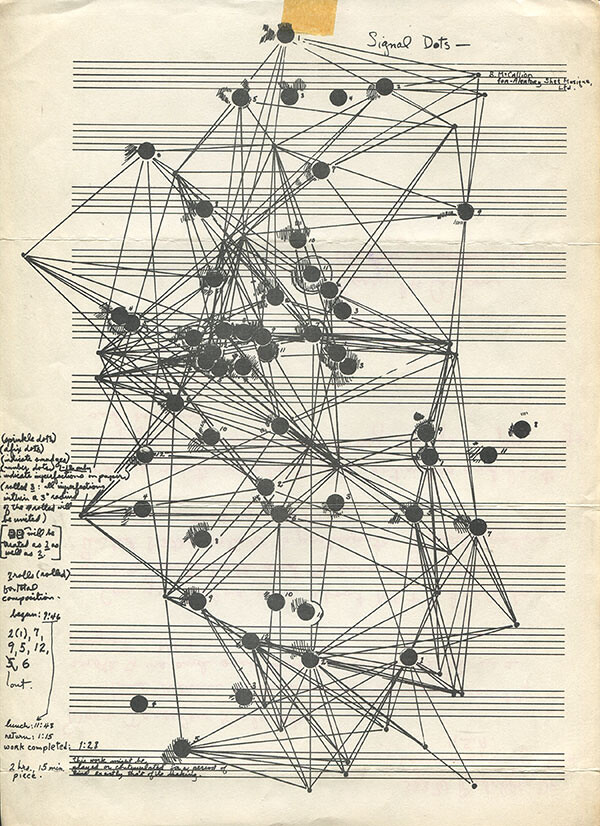

Barry McCallion, Signal Dots, 1972. Courtesy of the artist and Jarosław Kozłowski.

Other artists were soon using the list to carry out their own initiatives, taking NET into a new phase and realizing its potential for expanding communication in practice. Hungarian conceptualist László Lakner, for instance, sent a mailing inviting recipients to eat a piece of cake (torte) made of cardboard, providing a circle sliced into equal portions with one section labeled as having crossed over into “reality” (dated March 1, 1972). He invited participants to photograph themselves eating the slice, to hang it on the wall, or, in the event that they did not wish to do either, to give it to an ex-convict. His playful exercise demonstrated that there were many ways to take an image and make it real: consumption and display being two of these, with sharing as an important third option. Petr Štembera provided a reproduction of Hans Holbein the Younger’s painting of Charles de Solier of 1534–35 and requested that people copy the sitter’s gestures, photograph themselves doing so, and send him a copy. Kocman invited NET recipients to take part in a Butterfly-Environment Series: to “interpret” an environment for a given butterfly, sign it, and return the results to him in Brno. The hundreds of initial hours Kozłowski and Kostołowski had spent typing at the outset of the NET initiative could read as a gift of labor to the artistic community: by sharing the extensive contact list that they had compiled, the pair enabled countless others to share their work and to initiate new collaborations. What mattered was “exchange and getting to know people.” Above all, NET enabled artists to share what Kozłowski called artists’ “attitudes.”13

The project echoed the wider ethos of those times and a growing concern with the distribution of ideas rather than objects. Kozłowski was committed to overcoming boundaries between artistic forms. But most importantly from the point of view of international relations, he saw this as a parallel project to the overcoming of borders more widely by way of art, to create new dialogues modeled on friendship rather than rivalry. As he explained: “NET … aimed to cross not only geographical, ideological and political boundaries, but also those set by artists, which were in a sense breached by the conceptual revolt. All -isms, -arts, and other divides became irrelevant, it was all about art in its great diversity … utterly different articulations, attitudes and underlying ideas … a breeding ground for artistic friendships, which were arguably the most important value of the NET … I was immensely suspicious of all attempts at categorization or division.”14

Kozłowski’s assessment is in line with Lippard’s theorization of dematerialized art as being “all over the place in style and content, but materially quite specific,” referring in particular to “work in which the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious and/or ‘dematerialized.’”15 Both the article on the “dematerialization of art” and the NET project, in their own way, carried forward Dick Higgins’s pioneering use of the term “intermedia.” Higgins’s 1966 statement explained: “Our real enemies are the ones who send us to die in pointless wars or to live lives which are reduced to drudgery, not the people who use other means of communication from those which we find most appropriate to the present situation.” He went on to observe: “For the last ten years or so, artists have changed their media to suit this situation, to the point where the media have broken down in their traditional forms, and have become merely puristic points of reference. The idea has arisen, as if by spontaneous combustion throughout the entire world, that these points are arbitrary and only useful as critical tools, in saying that such-and-such a work is basically musical, but also poetry. This is the inter-medial approach, to emphasize the dialectic between the media.”16 Higgins clearly saw intermediality as a political statement of sorts: a matter of artistic solidarity in opposition to the political status quo. He was especially concerned with the Vietnam War and with the crisis in the labor movements in the United States.

And it was not only Eastern European artists who wrote asking to be included in NET. The US artist Barry McCallion, for instance, wrote to Kozłowski explaining that he had heard about the project from Hans Werner Kalkmann and that he would be happy to contribute and to “encourage other United States artists to participate if participation is something that you want.” The letter was penned on the back of a page of sheet music covered by an array of smaller and larger black dots—a piece completed in 2 hours 15 minutes, as he noted, between 9:46 and 1:23 with a break for lunch. The dots are connected in a complex formation, accompanied by a numerical system. Perhaps by chance, McCallion’s “chance-play” or “process-mapping” itself resembled a network.17

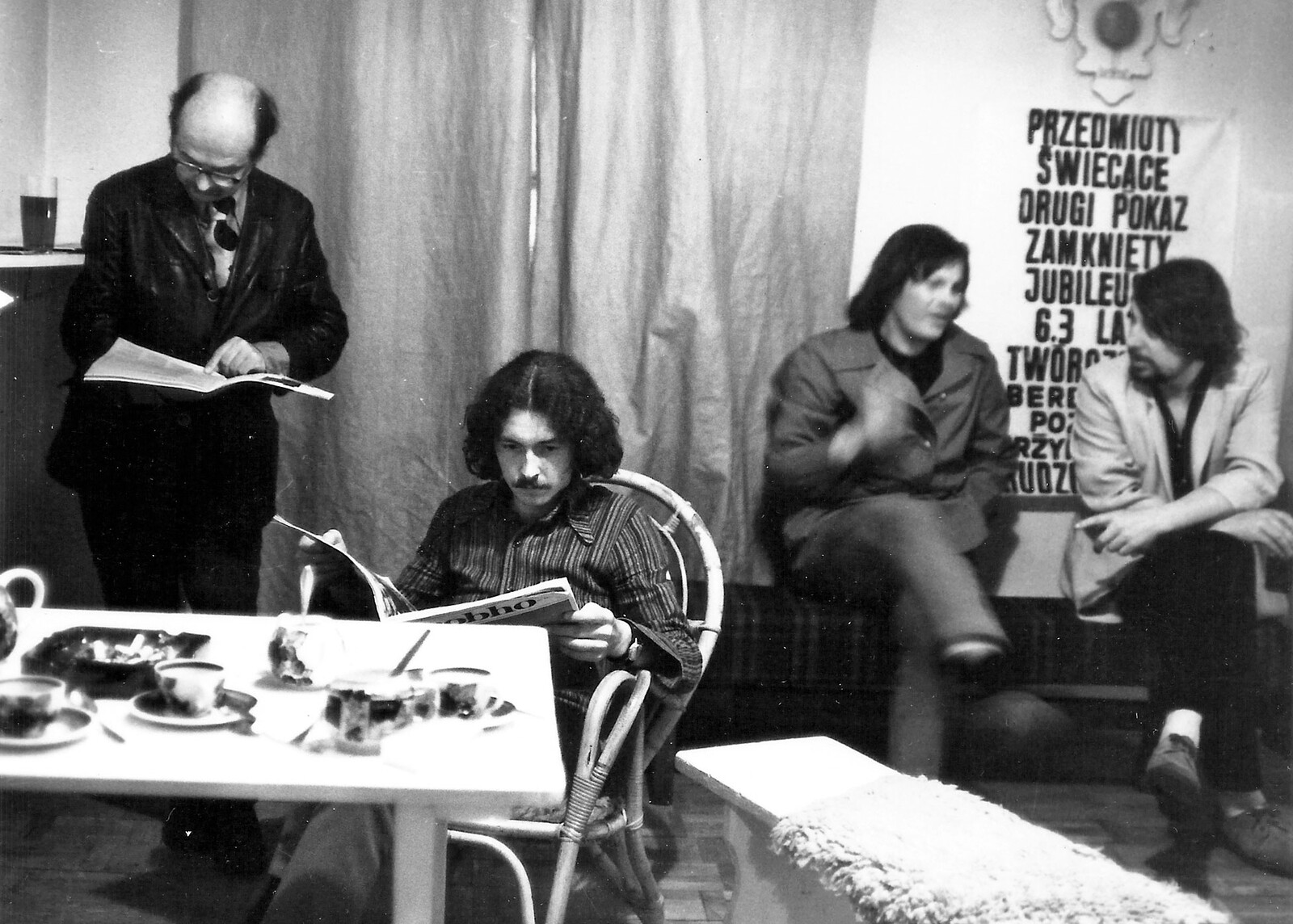

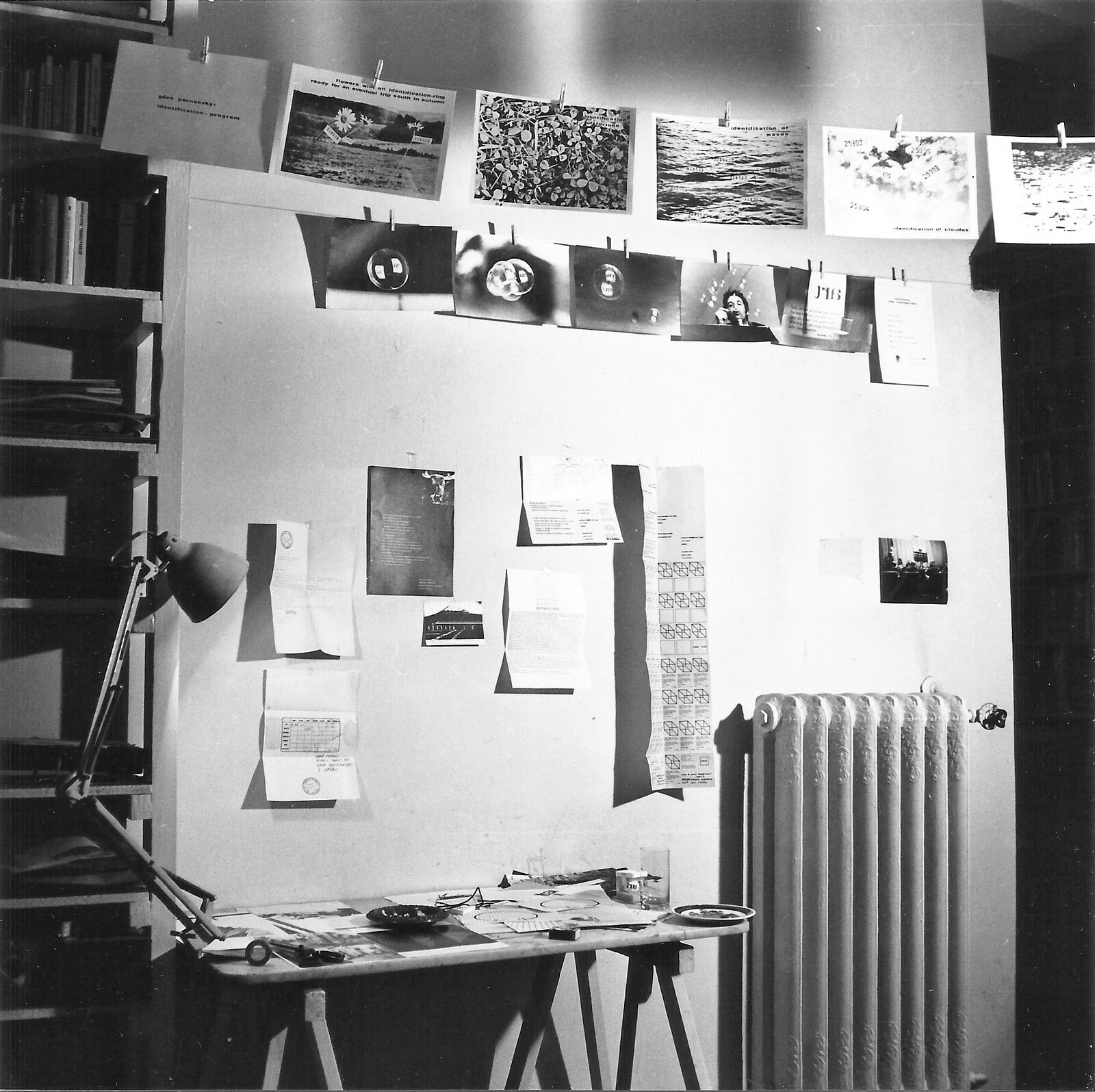

Kozłowski arranged a “reception” of the materials that the recipients of NET had sent him in response to the proposal in his apartment in Poznań on the evening of May 22, 1972. Though the reception was a way of sharing the materials that had arrived in the post (“after a month or two all sorts of mail arrived”) from twenty-four of those to whom they had sent the proposal, it was more informal than an exhibition, with materials hung all over the place, piled up on tables, and arranged on the floor for lack of space. Among them was Perneczky’s series on the theme of identification, suspended above a desk. Kozłowski had written to Perneczky (in German) in March 1972 after receiving a card from him, promising to put him on the NET appendix and send him a copy soon. He explained that he was planning to present the NET materials received to date in May and asked to include “Deine Concept Art.”18 The artist had invited just ten close acquaintances to the reception, making the raid that occurred forty-five minutes after the invitees arrived all the more shocking, since it was clear that one of his friends had informed on him. The materials were duly confiscated, including the film from the camera used to document the meeting itself: “They took it all down and took it away.”19

Interrogations and investigations followed for more than a year: “The leitmotiv was that we were founding an anarchist organization directed against the state … Later, they calmed down and a day before the court hearing which was due to take place I was informed that they had abandoned the idea.”20 Kozłowski’s everyday possibilities were curtailed, despite the decision to drop the case: he was unable to travel abroad, banned from teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts, and assigned to work in the library for the next five years.21 He continued to pursue the many new contacts that had been established as a result of the original mailing and the extended network that had subsequently evolved though. While he could not leave the country, his work continued to be shown internationally: “I sent my works by mail, as simple as that. At that time, I used to receive many invitations to present my work abroad, but my passport applications were automatically rejected … It was only in the late 1970s that I started traveling abroad.”22

He turned to self-publishing: “books offered freedom,” a means to circulate art without recourse to galleries and institutional structures.23 As he explains: “For us, in the East, books gave opportunities to find modes of expression beyond the official system of institutions. The only obstacle in the way was censorship.” Kozłowski devised ways to pass through the censorship process: “On some of my books, you can find the names of imaginary publishers … They were made up but necessary in order to get the censor’s stamp, which allowed you to print a hundred or so copies.”24 He distributed the books among friends and through his international networks and used his new contacts to find publishers for his artists’ books abroad, finding a home for his book Lesson with Beau Geste Press.

The Press had been founded by a collective of artists who had come together in rural Devon in England when Mexican émigré artists Felipe Ehrenberg and Martha Hellion moved there in 1970. Their rented manor house in Collumpton became Beau Geste Press, initiated by Ehrenberg and Hellion with a number of British collaborators, among them David Mayor. They would devote two issues of their magazine Schmuck to Eastern Europe—one issue entitled Aktual Schmuck edited by Knížák, and a survey of contemporary Hungarian art put together by Dóra Maurer and László Beke.25 Mayor, who has been described as “an obsessive letter writer,” was instrumental in the organizational aspects of the Press.26 His correspondence with Kozłowski about his book projects, outlining a range of options for printing and distributing, gives insight into the peculiar combination of ad hoc decision making and professionalism that characterized the Press as an independent enterprise. Mayor specifically asked that Kozłowski send him the NET list, showing that its significance went well beyond the Eastern European network it helped inspire.27

In addition to continuing to pursue such dialogues, Kozłowski found new ways to use loopholes in the system, in particular, the relatively relaxed rules relating to professional social spaces known as “clubs.” A second NET reception was held in October 1972 at the Club of the Creative Unions in Poznań and lasted just three hours. Kozłowski explains that what mattered was “to do another show and not to give up.”28 The second reception was more focused than the first, consisting of printed documentation from exhibitions held at the Art & Project gallery in Amsterdam suspended on wires strung between the walls, so that spectators could encounter the objects physically in space and handle the displays. This time there was no interference from the secret police.29

Together with three students from Adam Mickiewicz University, Kozłowski secured the use of a students’ club under the aegis of the Union of Polish Students (later called the Socialist Union of Polish Students) on shared terms with a student nightclub, to hold exhibitions four days a week. The Union provided minimal funding for costs such as invitations, printing, nails, wall paint, and photographic documentation.30 The international exchanges initiated by way of NET were central to the exhibition program of the new space, which they called Akumulatory 2 (a name taken from the neon sign over the space advertising car batteries). The aim of the gallery was “the presentation of exhibitions of avant-garde artists, representing—to as broad an extent as possible—the newest tendencies in Polish as well as world art.”31 They could rely on attracting a good crowd: “There was a permanent audience, a group of about forty people, who regularly came to the gallery, in addition to which there were sometimes more people. It was a very good audience, mostly artists and students from the academy and from art history, art historians, but also from the university, from other departments.”32

Kozłowski sought to run the space in as democratic a way as possible: “We worked with established and also with very young unknown artists. For example, we had an exhibition of work by Richard Long, and the following week we had a show by a fourth-year art student. There was no hierarchy.” Artists were simply invited to take over the space, without intervention by the organizers: “There was nothing formal, or written to say so, but still artists had a certain responsibility as a matter of principle. After all, they were all strangers to me and when they came to have their show, they would all live at my place. There was no state sponsorship.” There was still a requirement to provide evidence of proposed activities to the censors, but Kozłowski recalls that it was all something of a charade: “I had to take every exhibition invitation we proposed to print at Akumulatory to the censors, it all seemed a bit puerile. They were ready to buy or accept anything provided it was presented in such a way that it didn’t arouse suspicion; of course, it could have done, but it was a matter of interpretation. It was a simple-minded system.”33 Postal exchanges could be erratic, though: “Correspondence went missing. It was controlled at that time after all. There was in existence a paradoxical institution called the Office of Postal Exchange, which carried out checks. As regards all foreign correspondence, I assume that in those countries something analogous existed. And as a result the letters were lost. Contacts were often interrupted.”34

One of the first to be invited was Štembera, who later commented that “besides the Hungarians, the Poles were the only ones in Eastern Europe interested in what we were doing here.” What’s more, Poles had at their disposal “a whole mass of galleries which were not subject to censorship, outside the official structures ruled over by the communists.”35 It was a particularly difficult time in Czechoslovakia and the full weight of “normalization” had descended on artistic circles, with experimental artists expelled from the Union of Artists en masse, though Štembera was an employee of the Museum of Decorative Arts and not registered as an artist. Kozłowski “organized an exhibition in his name,” which ran from January 15 to 18, 1973.36 In addition to his documentation of the Transposition of Two Stones, he sent a selection of the Daily Activities, such as Tying Shoelaces and Button Sewing.37 The exhibition was called “Genealogy,” and the invitation consisted of a family tree.38

Andrzej Kostołowski and Jarosław Kozłowski, NET, 1971. Courtesy of Jarosław Kozłowski.

Besides being immensely active in disseminating his own work, Štembera was also attuned to the work of other artists in Czechoslovakia and in neighboring countries. Valoch recalls that he had initially mailed out “photographs of his land art installations and his conceptual books. Somewhat later came his Weather Reports … a very interesting transfer of meteorological news in the form of a mailed message.” Such pieces, Valoch argued, entailed a disavowal of the artist’s subjectivity and a desire to become “a mere middleman in the transfer of information.”39 Maja Fowkes likewise notes that the Weather Reports were “both a means of communication and a way to emphasize the problem of information transmission,” but she argues that this was not just any “banal, objective, and neutral scientific data” but “factual information about changes in the weather system,” pointing out that the weather is “something that everyone is exposed to” and represents “one of the most universal bodily experiences.”40 László Beke was an early recipient of these reports.

Štembera also wrote about art (like Valoch, who regularly contributed essays to artists’ exhibition catalogs).41 He provided a pioneering survey in English of experimental trends in Czechoslovak art in 1970, which was first printed in Puerto Rico and then reprinted in edited form in Lucy Lippard’s Six Years.42 The text, entitled “Events, Happenings, and Land-Art in Czechoslovakia: A Short Information,” was the first attempt by an artist to offer an international audience an overview of the contemporary Czechoslovak alternative art scene. Štembera made links between developments in Czechoslovakia and international trends, saying that “news trickled into Czechoslovakia about the work of the American happenings men, in the first place the names of A. Kaprow and the Fluxus group.” He argued that the information they received in the 1960s was “too incomplete and short to be capable of really influencing and forming anybody.” He noted, however, that “Knížák himself acknowledges Kaprow as one of the lasting personalities of happening art, and he proves this in 1968 with his trip to America, which was actually a trip to see Kaprow.”43 While paying his dues to Knížák as a pioneer, he remarked, perhaps a little pointedly, that “we have but a small choice of information at our disposal about the present-day activities of the indubitable leader of Czechoslovak happenings, Knížák … as he has been living in New York since 1968.” In his text, Štembera offered brief sketches of the activities of the Aktual Group, Stano Filko, Alex Mlynárčik, Eugen Brikcius, Eva Kmentová, Zorka Ságlová, Václav Cigler, and Hugo Demartini. The artist only referred to his own activities very modestly toward the end of the text, writing of himself in the third person: “Petr Štembera stretches out sheets of polythene between trees in a snow-covered landscape, and stretches out textile ribbons in a single color, paints rocks, etc.”[foonote Štembera, “Events, Happenings, and Land-Art in Czechoslovakia,” reproduced in Tom Marioni, Vision, no. 2 (1976), 42.]

Štembera played an active role in writing and disseminating the art history of his moment. This self-historicizing strategy coincided with a wider shift in the period toward a new fluidity between the positions of artist, critic, and art historian—a shift that is observable in the case of quite a large number of the experimental artists from Eastern Europe active in international circuits. Not least because of the absence of a supporting infrastructure, some artists felt compelled to contribute to the construction of a context for the reception of their work. Štembera’s artistic, social, and scholarly activities would all prove central to the expansion of the network. Among others, he provided the impetus for Klaus Groh’s landmark book Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa—the first survey of experimental art in Eastern Europe.

My previous publications on NET include Klara Kemp-Welch, “Autonomy, Solidarity and the Antipolitics of NET,” in SIEC—Sztuka dialogu/NET—Art of Dialogue, ed. Bożena Czubak (Warsaw: Fundacja Pro l, 2013).

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation with Klara Kemp-Welch,” ArtMargins 1, no. 2–3 (2012).

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation with Klara Kemp-Welch.”

Possibly a misspelling of the painter Zlatni Bojadijev.

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

Jarosław Kozłowski, “Art between the Red and the Olden Frames,” in Curating with Light Luggage, eds. Liam Gillick and Maria Lind (Revolver Books, 2005), 44.

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

One of the earliest events to strategically incorporate the post office into an experimental project in Poland had been Tadeusz Kantor’s happening The Letter of 1967 in Warsaw, discussed extensively in my Antipolitics in Central European Art.

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

Jiří Kocman, letter to Jarosław Kozłowski, June 17, 1972.

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

Jarosław Kozłowski, “Exercises and Paradoxes: An Interview with Jarosław Kozłowski by Bożena Czubak,” in Jarosław Kozłowski, Doznania Rzeczywistości i praktyki konceptualne 1965–1980 / Sensation of Reality and Conceptual Practices 1965–1980, exh. cat. (Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Znaki Czasu and MOCAK, 2015), 103.

Lucy Lippard, “Escape Attempts,” in Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, ed. Lippard (1973; rpt., University of California Press, 1997), vii.

Dick Higgins, “Statement on Intermedia” (1966), in dé-coll/age 6 (Typos Verlag and Something Else Press, July 1967).

Barry McCallion, email communication with the author, August 2017.

Jarosław Kozłowski and Andrzej Kostołowski, letter to Géza Perneczky, Poznań, March 29, 1972, reproduced in Géza Perneczky, “A KÖLN—BUDAPEST KONCEPT Bizalmas levéltári anyag az 1971-1972-1973-as esztendők magyarországi és nemzetközi Koncept Art mozgalmának a tudományos kutatásához,” unpublished manuscript, 2013, 141.

When the material was returned, Kozłowski also received the prints made from the confiscated roll of film, so that the secret police themselves ended up playing a part in the production of the documentation of the event they had interrupted. “‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.” See also Luiza Nader, “Heterotopy: The NET and Galeria Akumulatory 2,” in Petra Stegmann, Fluxus East: Fluxus-Netzwerke in Mittelosteuropa, exh. cat. (Künstlerhaus Bethanien, 2007), 111–25.

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

J. Kozłowski and J. Kasprzycki, “Alternatywna Rzeczywistość, Akumulatory 2,” Arteon no. 4 (2000), 49.

Kozłowski, “Exercises and Paradoxes,” 99.

Kozłowski, “Exercises and Paradoxes,” 99.

Kozłowski, “Exercises and Paradoxes,” 99.

For an overview of the Press see Donna Conwell, “Beau Geste Press,” Getty Research Journal no. 2 (2010), 183–92.

Donna Conwell, “Beau Geste Press,” 183.

David Mayor, letter to Jarosław Kozłowski, October 14, 1972, Kozłowski archive.

“‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

Art & Project was the subject of a MoMA exhibition in 2009 entitled “In & Out of Amsterdam: Art & Project Bulletin 1968–1989.”

Luiza Nader, Konceptualizm w PRL (Fundacja Galerii Foksal, 2009), 146–47.

Jarosław Kozłowski, “Program działalności Galerii Akumulatory 2 przy RO ZSP UAM w Poznaniu w roku 1972/1973,” dated October 10, 1972, cited in Patryk Wasiak, “Kon- takty kulturalne pomiędzy Polską a Węgrami, Czechosłowacją i NRD w latach 1970–1989 na przykładzie artystów plastyków” (PhD thesis, Instytut Kultury i Komunikowania, Szkoła Wyższa Psychologii Społecznej, Warsaw, 2009), 253.

Wasiak, “Kontakty kulturalne,” 261.

Kozłowski compares this situation with that in the West and finds that it was favorable: “Everything was more transparent in the East. But the perversity of ownership, and the standard concept of freedom that the West attached to the function of art, camouflaged very clever and insidious forms of pressure and control.” “‘NET,’ Jarosław Kozłowski in Conversation.”

Kozłowski cited in Wasiak, “Kontakty kulturalne,” 253.

Štembera cited in Wasiak, “Kontakty kulturalne,” 261.

An early example is Štembera’s participation in an exhibition with the laconic title “Encore une occasion d’être artiste” organized by Želimir Koščević at the Students’ Cultural Centre in Zagreb. See Novine Galerije SC (December 7–17, 1973).

Marika Zamojska, “Czechosłowacka awangarda w polskim życiu artystycznym lat 70,” Fort Sztuki no. 4 (2/2006) →.

Štembera distributed invitations to his Akumulatory 2 opening internationally, sending one to Jean-Marc Poinsot, among others.

Jiří Valoch, “Incomplete Remarks Regarding Czechoslovakian Mail Art,” in Mail Art: Ost Europa in Internationalen Netzwerk, ed. Kornelia Röder (Schwerin: Staatliches Museum, 1996), 61.

She also writes that as “weather is not subject to political decisions … it represents … the abstract notion of freedom.” Arguably, of course, we now know that weather is subject to political decisions, insofar as political decisions are central to halting the advance of climate change. Maja Fowkes, The Green Bloc: Neo-avant-garde Art and Ecology under Socialism (Central European University Press, 2015), 19. On a less environmentally minded note, the project inevitably also calls to mind Holly Go Lightly’s defense in Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s (released as a film in 1961) upon her arrest for visiting a notorious criminal involved in cocaine tracking while he was in prison (who would give her messages such as “Snow flurries expected this weekend over New Orleans” to pass on to his “agent”): “All I used to do would be to meet him and give him the weather report.” Štembera was doing the same, just passing on his weather reports, for his own reasons.

He was also committed to helping disseminate Western literature in Czechoslovakia in samizdat and translated key texts such as Fiore and McLuhan’s The Medium Is the Massage (1967) and, later, writings by performance artists such as Acconci (for Jazz Petit, edited by Karel Srp), presumably with the help of his wife, who studied languages (Štembera had studied social sciences).

Petr Štembera, “Events, Happenings, and Land-Art in Czechoslovakia: A Short Information,” Revista de Arte, Universidad de Puerto Rico, no. 7 (December 1970).

Petr Štembera, “Events, Happenings, and Land-Art in Czechoslovakia: A Short Information,” reproduced in Tom Marioni, Vision, no. 2 (1976), 42.

Category

This text is an excerpt from Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1965–1981 by Klara Kemp-Welch, published in February 2019 by MIT Press.