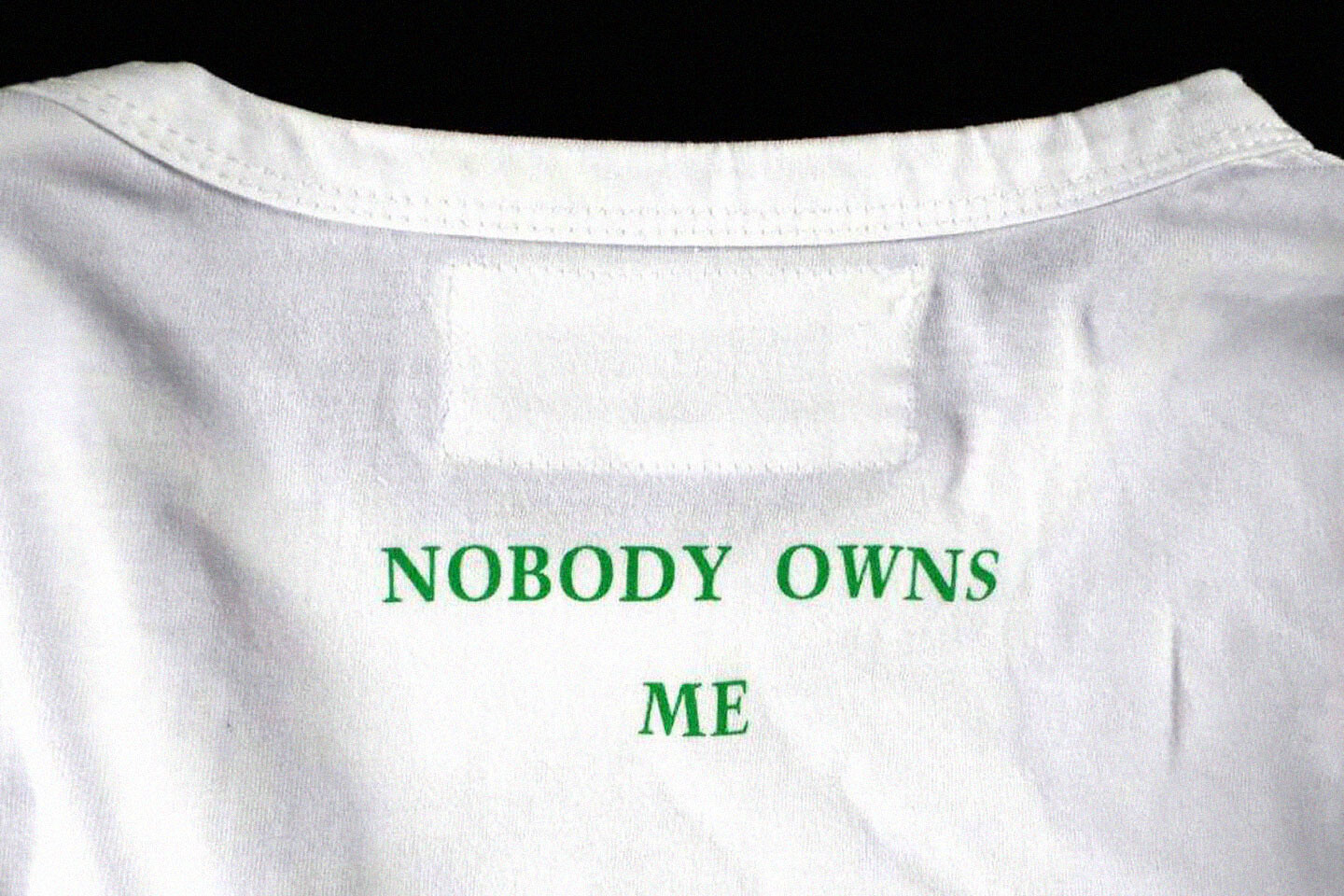

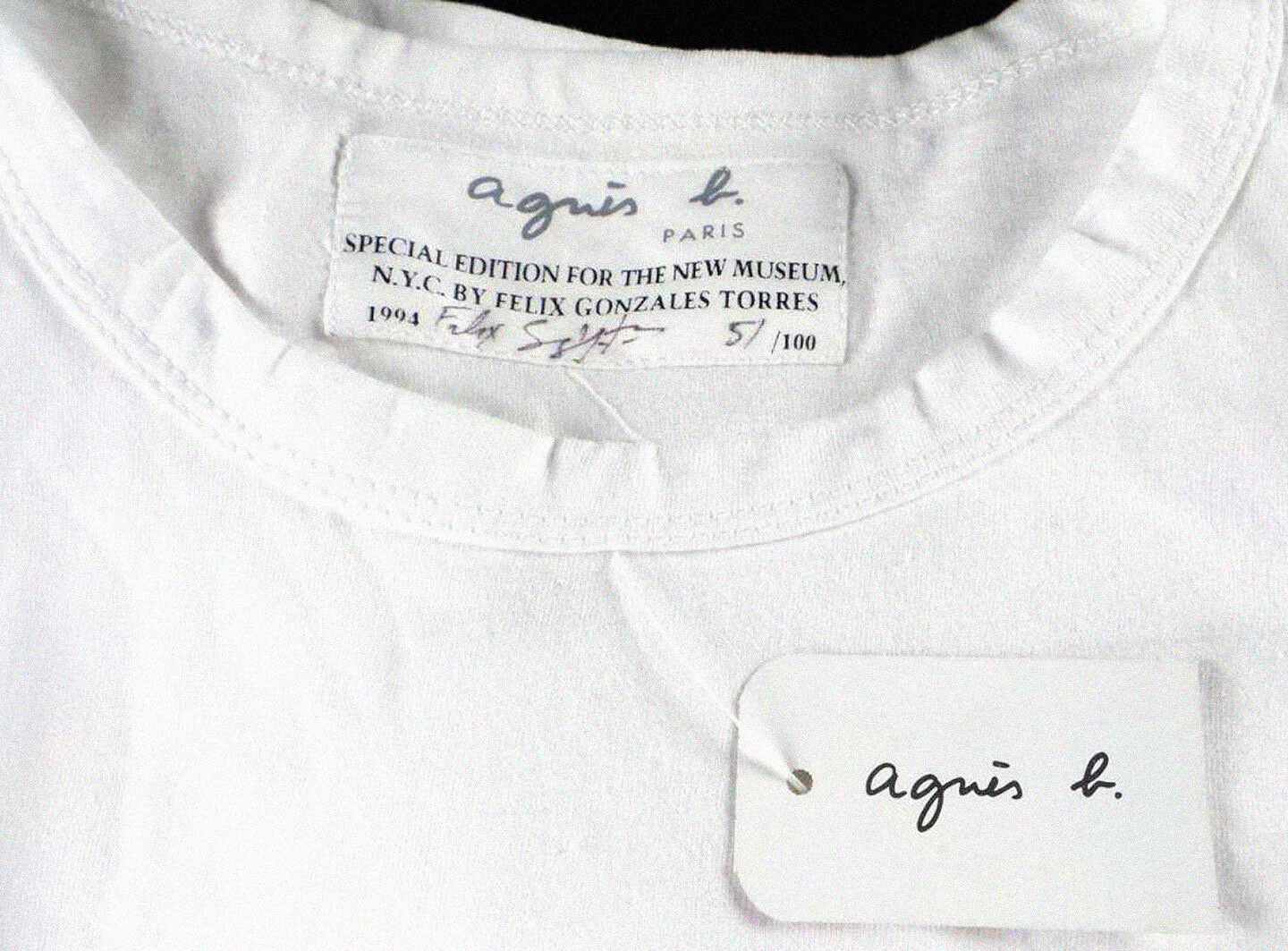

In 1994, Felix Gonzalez-Torres collaborated with the upscale French clothing manufacturer Agnès B. to create a limited edition T-shirt for a black-tie auction benefiting the New Museum of Contemporary Art, the formerly scrappy upstart that hosted his first solo exhibition in 1988. Intended to attract “new blood” (or new “bourgeois,” in a play on the name of Gonzalez-Torres’s new partner—the “b” in Agnes B. stands for the designer’s married surname, Bourgois) rather than “bejeweled ladies,” each T-shirt read “Nobody Owns Me” on the back, a fitting rejoinder to legal and politically motivated circumscriptions of private life, and, perhaps, to institutional eagerness to canonize the increasingly lionized artist.1 The slogan might have doubled as the subtitle of his certificates, which the artist renamed “Certificates of Authenticity and Ownership” in 1993. Issued amidst a contested social, legal, and political landscape, the certificates resonated against a juridical system that reaffirmed its allegiance to private property while undermining the privacy claims of some of its most disenfranchised subjects. A devastating reflection of how state interference usurped the role privacy formerly played in defining the unique space of the home, the US Supreme Court upheld the criminalization of sodomy in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986).

“How can we talk about private events,” Gonzalez-Torres asked, “when our bodies have been legislated by the state? We can perhaps talk about private property.”2 Among the most pervasive idioms for describing Americanness, private property held further implications for artists whose national and ethnic origin, racial background, and sexual orientation compromised their acceptance as Americans. As one of the few domains where cooperation occurred regardless of political preference or personal identity, the market held untapped potential as a political site. Deeply aware of how precarious life was for an openly gay, nonwhite artist living with AIDS, yet adamantly unwilling to capitalize upon his identity by wearing a metaphorical “grass skirt,” Gonzalez-Torres stated it was “more threatening” that “people like me operate as part of the market.”3 Through certificates that embodied rather than represented ownership by metabolizing elements of copyright and contract, he navigated market conditions and art-world protocol. Eventually shifting his works away from the metrics of supply, Gonzalez-Torres recast them as dynamic sources of doubt according to the legal frameworks to which he and they were unavoidably subject.

Owning a Gonzalez-Torres work meant thinking about ownership as a continuous process, subject to unexpected change. The candy piles and paper stacks of Gonzalez-Torres might be compared to legal notions of alluvion, or the extension of a landowner’s property by deposits carried by wind and water, and its mirror opposite, diluvion, or the phenomenon of a landowner’s property being diminished by erosion or other forms of attrition caused by natural forces. Land bounded by water tends to change in size and aspect, a recognition that grounds what common law holds as the nature of long-term ownership of property, its inherent subjection to gradual change.4 Likewise, if the idea of change is inherently part of the works, it follows that they can only be truly owned when held for long periods of time, or at least long enough so that they can be executed and shown in different ways.

The terms of the certificates make it potentially more difficult to sell a Gonzalez-Torres than other works. But by continuing to offer what appears to be an endless supply of paper regardless of how it is consequently used or even whether there is sufficient demand, Gonzalez-Torres thwarted the usual interaction on which economics depends. He openly declared his interest in the subversive potential of having more than one original at a time, noting how his replenishable stacks made at “the height of the ’80s boom” undermined the idea of having an original work: “You could show this piece in three places at the same time and it would still be the same piece. And it was almost like a threat—not only a threat but a reinterpretation of that art market.”5 Miwon Kwon describes this as “a struggle to establish new terms or systems of valuation that can respond adequately.”6 Letting audiences freely take the constituent components they would have seen as the work struck Gonzalez-Torres as perhaps the only response to a context where buyers were intensely, even pathologically, anxious to affirm their ownership status.

The certificates potentially ascribe to him and his estate the right to control the product, a notion discussed in work-for-hire cases.7 When Gonzalez-Torres drafted his first certificates, the US Supreme Court considered Community for Creative Non-Violence, et al., v. James Earl Reid. At issue was whether the artist producing a commissioned work retains copyright ownership or if such ownership belongs to the organizer commissioning the work. The commissioning organization in the case claimed ownership on the basis that it had “directed enough of [the artist’s] effort to assure that, in the end, he had made what they, not he, wanted.”8 The court decided in favor of the artist, both because it determined the artist was not an employee of the commissioning organization and because of the amount of labor and time he spent in creating the work.9 The decision supported an earlier model of authorship based on artists directly engaging in the production of work.

The language of Gonzalez-Torres’s certificates resonates with the plaintiff’s argument in Community for Creative Non-Violence: it “directs” enough of the owner’s efforts to ensure that the work is what the artist wanted. It casts owners as subcontractors, and possibly even as virtual work-for-hire employees. Kwon states that “not only did Felix know that he would not be able to determine the work’s future form,” he “was indebted to the owner’s involvement.”10 Those buying Gonzalez-Torres works were not his employees; nor were they paid by him or his representatives. Owners decide when to execute the terms of the certificate. But by delegating many of the functions ordinarily expected of artists, including sourcing materials and putting them together to create a tangible work, Gonzalez-Torres shifted the role, and perhaps the burden, of the artist-as-service-provider onto owners in the form of a unique, and thus desirable, experience.11

[

More significant was how the certificates’ openness augured the possibility of an authorship model more aligned with the free distribution of otherwise copyrightable work than with defensive and punitive models of copyright. In 2004, the artist Sturtevant made Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (America), a near facsimile of Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (America). Known since the mid-1960s for works resembling other works by well-known artists in a host of media, including Land Art and performance, Sturtevant heralded a recursive model of creation where originality centered on assessing existing data and making subsequent choices on multiple scales of operation. Her process was hardly by rote, especially vis-à-vis Gonzalez-Torres, whose “intentions,” Sturtevant remarked, one “really had to know.”12 Although Sturtevant was not privy to the younger artist’s certificates, the flexibility of Gonzalez-Torres’s giveaway works had long been known in art world circles; Susan Tallman in 1991 described how an artist, on asking whether she should preserve a sheet from a stack, was told “she should do with it whatever she liked.”13 The sheet no longer belonged to Gonzalez-Torres, yet the freedom granted may have obligated some takers to embark upon their own creative activity. Other artists whose works closely resemble those of Gonzalez-Torres in spirit as well as form also suggest how Gonzalez-Torres’s certificates embrace a non-adversarial model of copyright based on producing and sharing knowledge for the many.

On a different note, can a replenishable Gonzalez-Torres work ever be mutilated or even destroyed? Certificates accompanying the dateline portraits grant the owner “the right to extend or contract the length of the portrait, by adding or subtracting events and their dates.”14 According to this logic, the adding and subtracting of events can potentially change the work until it is no longer recognizable as a work by Gonzalez-Torres, as Kwon discusses.15 Candies in a Gonzalez-Torres heap may not themselves be the work, yet to exhibit one piece only might be seen as an unlawful attempt to show the work in an “altered, mutilated, or modified form.”16 Not replenishing the piles or stacks might amount to destruction as a kind of death since viewer interaction, a key part of the work, can only occur when the idea takes physical form.

Contrary to US copyright law, which protects “expression” but not the idea from which it stems, and in alignment with art critical and commercial practice, the certificates of Gonzalez-Torres fixed his works as a function of their conception rather than execution. Early certificates specified how “the physical manifestation of this work in more than one place at a time does not threaten the work’s uniqueness since its uniqueness is defined by ownership.”17 “Uniqueness defined by ownership” referred to how the status of ownership depends more on whether the buyer has adhered to the conditions of each certificate than the physical expression of that adherence. For paper stack works, owners have the right to replenish the stack or simply allow the pile to disappear completely. The work need not be realized as a “fixed, tangible” object.

Yet those charged with protecting a Gonzalez-Torres work often defended the manifestation rather than the idea. Museum guards, whom Gonzalez-Torres deemed significant to the viewing experience, have been especially vigilant. In her review of the 1995 Guggenheim retrospective, Clara Hemphill wrote of how a guard scolded her for allowing her son to throw Gonzalez-Torres’s candies in the air: “It [the work] is supposed to invite interaction—but not too much!” he said. She later quipped that “perhaps Gonzalez-Torres’ piles of candies become art when the museum guards yell at you not to touch them too much.”18 To the Guggenheim guards and many viewers, however, the candies constituted the work, a view applied to sheets of paper in the stack works. Although several certificates state that individual sheets “do not constitute a unique piece nor can be considered the piece,” many have been offered for sale.19 Rosen has noted how museums, apprehensive that their stack works might disappear even before a show began, asked Gonzalez-Torres permission to prevent viewers from taking sheets during an opening.20 That he eventually complied with such a request was a gesture of compromise suggesting an awareness of the very real concern of institutional owners concerning the possible destruction of their works acquired in the name of the public good.

The blurred distinction between idea and expression is further borne out by differences in insurance costs. Those borrowing the work bore the burden of insuring it for the cost of its production. For lenders, the candies indicated a right they purchased from the artist (in one owner’s words, a loan meant giving someone else the temporary right to “reproduce a simulation”).21 In some cases, a relatively high value was assessed when identical replacements for a work’s components could not be sourced, an indication of owners’ attachment to objects.22 For the candy spills and paper stacks, the cost amounted to less than a thousand dollars, a slim fraction of what the works they embodied might otherwise fetch on the market or at auction. Yet the Andrea Rosen Gallery has suggested that borrowers of Untitled (Aparición) should “make the printer aware that the material they are reproducing is actual artwork.”23 Gonzalez-Torres himself casually referred to the paper stacks as “sculptures,” a description that his printer took up in referring to reams of paper generally: “His idea about his own work has been changed.”24

Scott Myles, ELBA (installation view), 2010. In the work portrayed, Myles writes the number “2010” (though it resembles ”2%”) on González-Torres’ poster Untitled (Passport), 1991.

Despite being a class of individuals with vested economic interests in preventing the mutilation or destruction of an artwork, owners of Gonzalez-Torres works differed considerably on what was a genuine risk. Some worried about the actual physical destruction of the constituent parts of a manifestation. Elaine Dannheisser, one of Gonzalez-Torres’s first collectors, reportedly warned museums that the candy spill works could be subject to a rat infestation, as hers was in 1994. Most institutions took no special measures to guard against such an incident, yet one used sugarless candy as a precaution, therefore suggesting an attachment to the idea of the work as inherently defined by tangible objects.25 Many owners were fairly nonchalant about damage when it did happen, largely because of Gonzalez-Torres’s insistence that the physical manifestation of his ideas was not the work itself, but an “exhibition copy,” or, perhaps to diminish the stigma of describing a work as a copy, a “simulation of the work.”26 For museums, it lessened the burden of liability. “There’s nothing that can happen to this work [Untitled (1991–93), a billboard work],” wrote Amada Cruz while preparing for the artist’s 1994 retrospective at the Hirshhorn Museum: “It’s a refabrication—even if someone slashes the work—it’s a simulation.”27 Legal scholars Jack Balkin and Sanford Levenson have described authenticity in the law as a condition determined by a “community of consensus.”28 Yet during the years between Gonzalez’s first solo show in 1987 and his death in 1996, community formation was still in process, as evidenced by the particular caution exercised by museums displaying works on loan for whom having an authentic Gonzalez-Torres meant interpreting his intentions. Gonzalez-Torres may have found it “amusing” to receive endless faxes from museums asking “what they should do,”29 but for museums responsible for showing genuine work, the lack of consensus surrounding how an authentic work of his might function and what it would look like was a pressing concern. When a candy spill work, Untitled (Lover Boys), was shown at the 1991 Whitney Biennial, the museum interpreted Gonzalez-Torres’s instructions allowing the public to “take one candy if they want” to mean that audiences should not be actively prevented from taking candies but that they should not be encouraged or directed to do so.30 Conversely, MoMA, which owned Untitled (Placebo), granted the Hirshhorn the option to display a sign allowing the public to take the candy.31

Most owners erred on the side of extreme caution, perhaps because in signing the certificates they also contracted with the art world at large. Many behaved as if they knew the VARA provision allowing changes to a work caused by its constituent materials or the passage of time so long as they were not the result of “gross negligence,” or carelessness so serious as to exceed what one might expect from a reasonable person.32 Yet institutional manifestations of Gonzalez-Torres’s work seemed governed by perceptions of civility and decorum, to the point that he sometimes had to intervene. Struck by how viewers of his work at MoMA ate the candies, then threw their wrappings back into the pile, he asked that the museum leave the wrappers where they were despite the museum stipulating that the wrappers be discarded.33

The surest proof of owner intention may be the loan agreements owners use to lend their Gonzalez-Torres works to other institutions for an exhibition.34 By 1994, several loan agreements instructed lessees on how to install works and went so far as to indicate that the work must “not be transformed in any way” from its original dimensions.35 In response to owner questions arising in the process of installing works, the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation developed templates for more elaborate loan agreements, including recommendations for producing and installing the works. For owners using the Foundation template, the loan agreement becomes a de facto assertion of proprietary rights that reads as being more restrictive in the scope of rights granted than the actual certificate.

A signed “Agnes b.” t-shirt with the sentence “Nobody Owns Me” by Felix Gonzales Torres printed on the back. The t-shirt was issued as a special edition for the New Museum, NYC, 1994. It is a signed edition 5/100. Here portrayed is a size large, like-new item, with the original label included. It was auctioned off on www.liveauctioneers.com.

The certificates of authenticity rehabilitated the general tenor of collector-artist relationships, where the former is concerned primarily with securing and maximizing exchange value and the latter with protecting various rights after a work’s sale. By granting owners considerable flexibility in determining how their purchases might appear, Gonzalez-Torres’s certificates treat collectors almost like collaborators. Not surprisingly, many private collectors demonstrate unusual vigilance in following certificate recommendations. The certificates might also be read as invitations for owners to prove themselves as something other than consumers or property collectors interested primarily in maximizing their economic interests. Such owners might very well define what art historian John Tain calls the “rogue” or “activist collector,” who, in lieu of collecting artworks as if they were any other asset type, dedicates herself primarily to prolonging the lives of the artworks she has.36 Such collectors grew in number and prominence in the 1990s by establishing their own foundations, museums, and other institutions as a means of intervening in the ways artworks were discussed, produced, and circulated.

Gonzalez-Torres, or at least his estate, seemed to anticipate this breed of collector when the word “utmost” started to be paired with “discretion” in the certificates. A common filler in many legal agreements, “utmost” was added to replace an earlier term introduced in 1994 in which owners had to secure the express written permission of the artist if they wanted to lend his works elsewhere. “Utmost discretion” recalled similar phraseology in tort law, where “utmost” simply refers to a reasonable standard of care. Against a contractual context, “utmost” reads as mostly rhetorical window dressing. More specific was “caretaker,” a term that appeared in a certificate for a text portrait sold jointly to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago in 2002; the owner was “the caretaker he [Gonzalez-Torres] entrusted with this work’s evolution.”37 The “caretaker” designation suggests ownership as a temporary condition, one in keeping with the artist’s apparent efforts to write noneconomic qualities like respect and trust into a world measured by assessments of economic value. The operative relationships were no longer determined by categories of “author,” “buyer,” “seller,” and “owner.” Instead, the certificates demanded from owners proof of their integrity, or in this case, of their ability to fulfill another’s will even if it meant having to act against their best economic interests.

Gao Lei, Untitled (Microscope), 2017. Epson print. The backdrop in the photograph originates from Félix González-Torres’s stacks of blue paper from his solo exhibition at the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai.

Realizing a Gonzalez-Torres work remains a carefully regulated commitment, tempered by myriad contests between buyer and seller, artist against both buyer and seller, and even the buyer against her own rights as an owner. The theoretical value of the certificate lies in the owner being able to freely show a particular collection of tangible objects as Gonzalez-Torres’s works without the risk that he or she might be sued.38 The risk was especially real for museums, characterized by their keen aversion to all forms of legal liability and its vigilance in safeguarding tangible property. One thinks, for instance, of how the Hirshhorn had to make sure that the lightbulbs used in the Gonzalez-Torres retrospective had to be remade to adhere to national safety codes.39 To ostensibly reassure owners, the Hirshhorn promised to exercise “utmost care,” a tort law concept mandating an extraordinary degree of caution for others’ safety where even the slightest negligence is grounds for liability.40 Applied mostly to companies providing accommodations or the transport of goods and people, “utmost care” signals residual attachment to ingrained views of artworks as objects, even when the certificate clearly permits the work’s reconfiguration, and even reconstruction.41

The artist himself instructed anxious museums to do “whatever you want,” a response that not only knitted together obligation and choice as a function of desire and freedom but also suggested a refusal of the dualistic thinking categorizing queers as criminals via decisions like Bowers v. Hardwick.42 The point was not simply about giving owners freedom of choice, but rather that there was no one right choice, just as Justice Harry Blackmun argued in Bowers that there was no one right form or approach to intimacy.

Doing “whatever you want” had other consequences, not least for Gonzalez-Torres himself. Although he disallowed individual candies and paper sheets the status of artworks, Gonzalez-Torres thought it “weird” to see audience members “come into the gallery and walk away with a piece of paper that is ‘yours.’”43 Recounting how another artist took twenty to twenty-five sheets from one of his paper stacks, he was initially pleased to think that they might become the basis of another’s work, only to find that she had thrown them away.44 His dismay, repeated over time, might have triggered his proprietary instincts along with a generous helping of pique. In a later interview, the artist spoke of making conventional photographs he could “just” hang on “the fucking wall … I don’t want the public to touch them.”45

In “Civil Rights Now,” one of the more important group exhibitions featuring Gonzalez-Torres’s work during his lifetime, an implicit message was how the demand for rights was not simply a vague call to right injustices, but about cultivating an environment of sympathy towards “common issues of justice” underlying civil rights.46 The challenge lay in grappling with difficult, and often illegible, feelings. True to form, the market has capitalized upon feelings—since the mid-2010s, financial institutions have described art as “passion assets” in presumed reference to the emotional bonds between owners and their possessions. Yet even now, the elliptical language of Gonzalez-Torres’s certificates continue to kindle a host of feelings mirroring the unevenness of a world marked by failure and redemption. From this it becomes possible to imagine action beyond the official and unofficial laws now governing the relationships created by the sale of an artwork—relationships formed in the names of commerce and love alike.

Alexandra Peers, “Charities Draw Younger Donors With Hip Events and Door Prizes,” Wall Street Journal, April 25, 1994.

“Joseph Kosuth and Felix Gonzalez-Torres: A Conversation,” Art & Design 9, no. 1–2 (1994): 76.

Tim Rollins, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (A.R.T. Press, 1993), 20.

Kevin Gray and Susan Francis Gray, Elements of Land Law, 5th ed. (Oxford University Press, 2009), 12–13. I thank Emma Waring for this reference.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Gonzalez-Torres, Felix,” Hans Ulrich Obrist, Interviews 1 (Charta, 2003), 311.

Miwon Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art: FGT and a Possibility of Renewal, a Chance to Share, a Fragile Truce,” in Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ed. Julie Ault (SteidlDangin, 2006), 295.

Aldon Accessories Ltd. v. Spiegel, Inc., 738 F.2d 548 (2nd Cir., 1984).

Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 652 F. Supp. 1457 (D.D.C, 1987).

Community for Creative Non-Violence et. al. v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730 (1989).

Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art,” 308.

The issue of the service provider and the presumptive psychological toll of fulfilling services contracted is poignantly illustrated in Employment Contract (on Felix Gonzalez-Torres), a twenty-two-minute film by Pierre Bal-Blanc, who performed as a dancer in Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Go-Go Dancing Platform) in 1991. For a discussion of the film see Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (Verso, 2012), 235. The final shot of the film shows the artist physically running away from the museum.

Oral history interview with Elaine Sturtevant, July 25–26, 2007. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution →.

Susan Tallman, “The Ethos of the Edition,” Arts 61, no. 1 (September 1991): 14.

Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art,” 304. The wording is from the certificate accompanying “Untitled” (Portrait of the Cincinnati Art Museum), 1994 (ARG #GF 1994-9).

Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art,” 304.

A comparable situation might be when a wrapped Christo work is unwrapped. The unwrapping might constitute an unlawful alteration, although such incidents have occurred only by accident.

Quoted in David Deitcher, “Contradictions and Containment,” Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Catalogue Raisonné (Cantz, 1997), 106.

Clara Hemphill, “Is It Art, Or Is It Candy?,” New York Newsday, April 18, 1995.

Two sheets from Untitled (Somewhere better/Nowhere better) (1990) were sold on eBay in October 2015 for $44.25 →.

Andrea Rosen, “‘Untitled’ (The Neverending Portrait),” Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Text, ed. Dietmar Elger, exhibition catalog (Cantz, 1997), 46–47.

Estelle Schwartz, letter to James Demetrion, March 17, 1994. The work referred to the paper stack Untitled (1989/90). Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–1994, box 1.

Philippe Ségalot, letter to James Demetrion, May 16, 1994. “As the particular white beads this work is partly composed with are impossible to find anymore, the work (Untitled (Chemo)) couldn’t be identically replaced should it be damaged during the show and this is why I have indicated its market value.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Andrea Rosen Gallery, Felix Gonzalez-Torres Stacks, undated. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, quoted by Bruce Ferguson, Rhetorical Image (New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1990), 48.

Barbara MacAdam, “Sweet Horrors,” Art News 94, no. 5 (May 1995): 40.

“Exhibition copy” was used by institutions; they were also called “extra copies.” Letter from Amada Cruz to Philippe Ségalot, September 12, 1994. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Amada Cruz, untitled note to registrar Barbara Freund, May 13, 1994. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1. Hirshhorn staff expressed great concern over how to replace crushed beads, a problem that meant asking what constituted an acceptable substitute to the lender to whom the museum owed a legal responsibility via the loan agreement.

Jack Balkin and Sanford Levinson, “Interpreting law and music: Performance notes on ‘The Banjo Serenader’ and “The Lying Crowd of Jews,” Cardozo Law Review 20 (1999): 1513–72.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, “KünstlerInnenporträts – Auszüge: Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” Der Standard, January 10, 1996.

Richard Marshall, letter to Richard Gagliano, April 12, 1991; Registrar Memorandum to Public Education and Security, April 21, 1991. Whitney Museum of American Art, Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Exhibitions 1931–2000 Archives, “1991 Biennial,” Box 155.

Letter from Cora Rosevear to James Demetrion, April 28, 1994. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

17 U.S. Code §106A (c)(2)

Jo Ann Lewis, “‘Traveling’ Light: Installation Artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres Shines at the Hirshhorn,” Washington Post, July 10, 1994. Terms of the MoMA installation were set forth in a letter from Cora Rosevear to James Demetrion, April 28, 1994. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

The Foundation takes a role by providing loan guidelines, or sample loan agreements upon request, although owners are not obligated to do so.

Jennifer Flay, letter to James Demetrion, March 17, 1994. Flay was conveying the wishes of Marcel Brient, the owner of Untitled (Blood) (1992), which the Hirshhorn borrowed. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

John Tain, “The Things You Own End Up Owning You: Art in the 1990s,” unpublished symposium comments, University of Michigan, October 24, 2015.

As quoted in Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art,” 308. From the certificate for Untitled (1989) (ARG-#GF 1989-20), 4.

Emma Waring, email communication with the author, November 11, 2014.

Kathy Watt, memorandum to Amada Cruz, January 11, 1993. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Letter from Amada Cruz to Philippe Ségalot, April 4, 1994. Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Keith N. Hylton, Tort Law: A Modern Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 262.

Obrist, “KünstlerInnenporträts – Auszüge: Felix Gonzalez-Torres.”

Rollins, 13.

Rollins, 13.

Jim Lewis, “Master of the Universe,” Harper’s Bazaar, January 1995, 133.

Maurice Berger, “The Crisis of Civil Rights,” Civil Rights Now (Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, 1995), 46.

Category

Subject

This text is excerpted from Joan Kee, Models of Integrity: Art and Law in Post-Sixties America, forthcoming from University of California Press in March 2019.