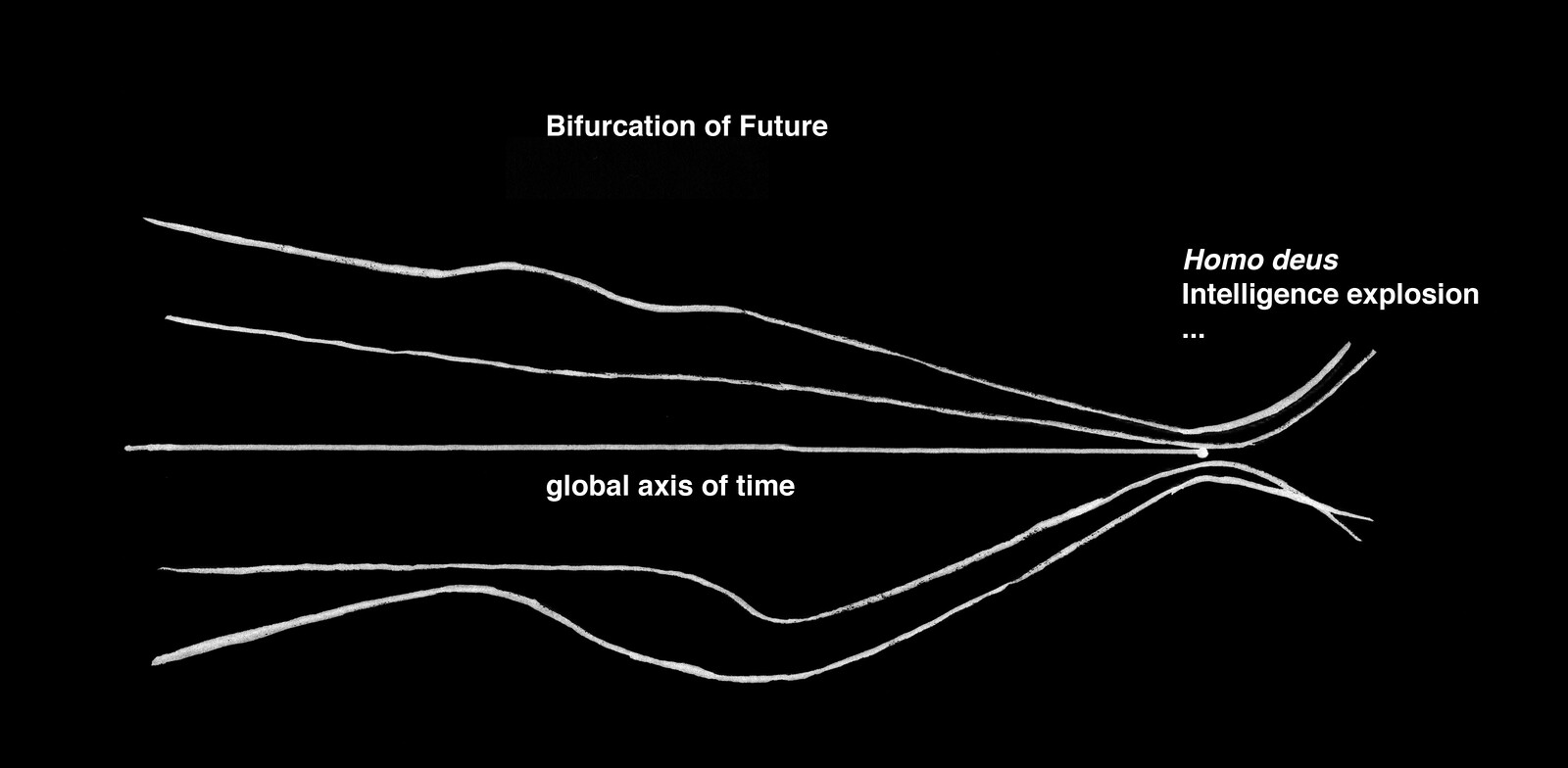

On the other hand, we may understand Kissinger’s end-of-Enlightenment claim as marking the full realization of a single global axis of time in which all historical times converge into the synchronizing metric of European modernity. It is the moment of disorientation—a loss of direction as well as of the Orient in relation to the Occident. The unhappy consciousness of fascism and xenophobia arises from this inability to orient: as a response, it offers an easy identity politics and an aestheticized politics of technology. More broadly, such a disorientation can be seen as a desirable and necessary deterritorialization of contemporary capitalism, which facilitates accumulation beyond temporal and spatial constraints. War is the technique of disruption par excellence, vastly more effective than Uber and Airbnb.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Common or Spectacled Caiman with South American False Coral Snake, c. 1705–10. Watercolor and bodycolor with gum arabic on vellum.

Wars have evolved to many more frames per second in the years since the war on Iraq began (and have indeed accelerated because of that war), and we continue to participate in them no matter how undecided, baffled, or distant we are towards them—and no matter who “we” are (just yet). We participate in war because we consume its cruel images, and often at a mediated distance. The Lebanese writer and translator Lina Mounzer profoundly wrote in 2015: “I have buried seven husbands, three fiancés, fifteen sons, and a two-week-old daughter … I have watched my city, Maarrat al-Numan, burn, I have watched my city, Raqqa, burn, I have fled Aleppo … All this I have watched from my living room in Beirut.”

Photographic images could be considered particular forms of violence spurred by a given power/knowledge that is responsible for “general violence.” Conceived in this way, images could be performative as they enact ideology, as they exemplify, codify, and translate written and unwritten laws and social hierarchies, as they bestow or remove citizenship, and as they exert epistemic violence. Images do all these things in a particular mode and manner depending on the specificities of their respective medium and form. Visual activism, or the realm where images are put to militant use, like in the cases of Akhter and Ferdous, is one of the customarily invoked strands of practice that supposedly enables the production of visualities that oppose and contradict the “general violence” in which photography arguably takes part. So what exactly is the place of violence in activist image journalism and in modes of visual protest? And what may be the limit of such violence with regard to the violences of the (neo)colonial order?

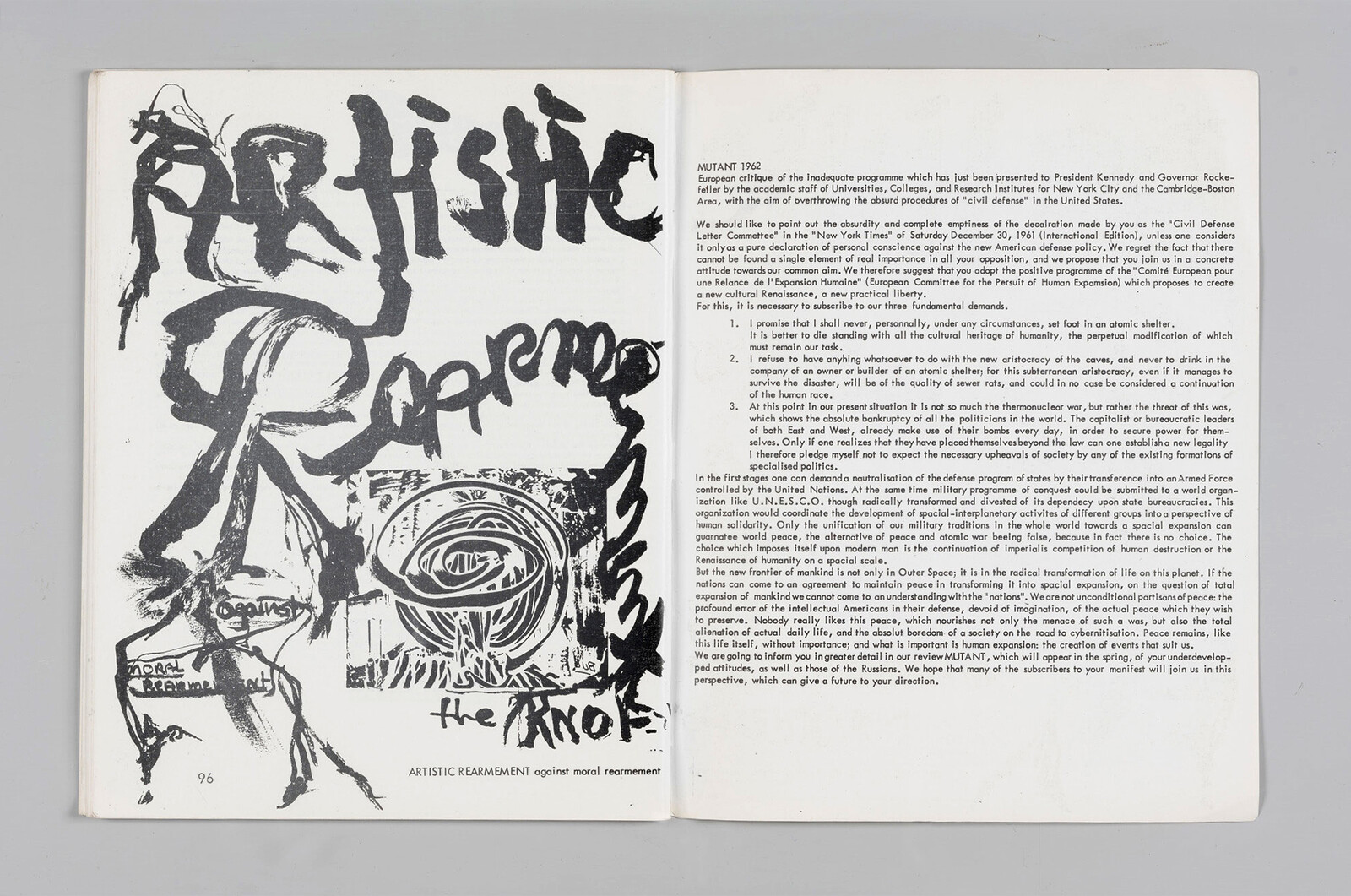

While there are notable exceptions, especially in literature and the cinema, on the whole the art of the “first responders” of the late 1940s and ’50s tended to stage the postwar nuclear age as existential tragedy rather than as a political issue. In his conclusion, Newman asks and asserts: “Shall we artists make the same error as the Greek sculptors and play with an art of overrefinement, an art of quality, of sensibility, of beauty? Let us rather, like the Greek writers, tear the tragedy to shreds.” In much 1950s art, the possibility of a total and remainderless destruction of culture and of life is evoked, yet at the same time symbolically conquered through the proliferation of tattered, ravaged, or starkly simplified and thereby sublime and existential forms. In 1958, during an antinuclear conference in Tokyo, the philosopher and antinuclear activist Günther Anders visited the memorial of the nuclear bombardment in Hiroshima. Its abstract arch, which only appeared symbolic “because the non-functional always suggests symbolism,” reminded him of American abstract expressionism and its endorsement by the US, even by the War Department itself.

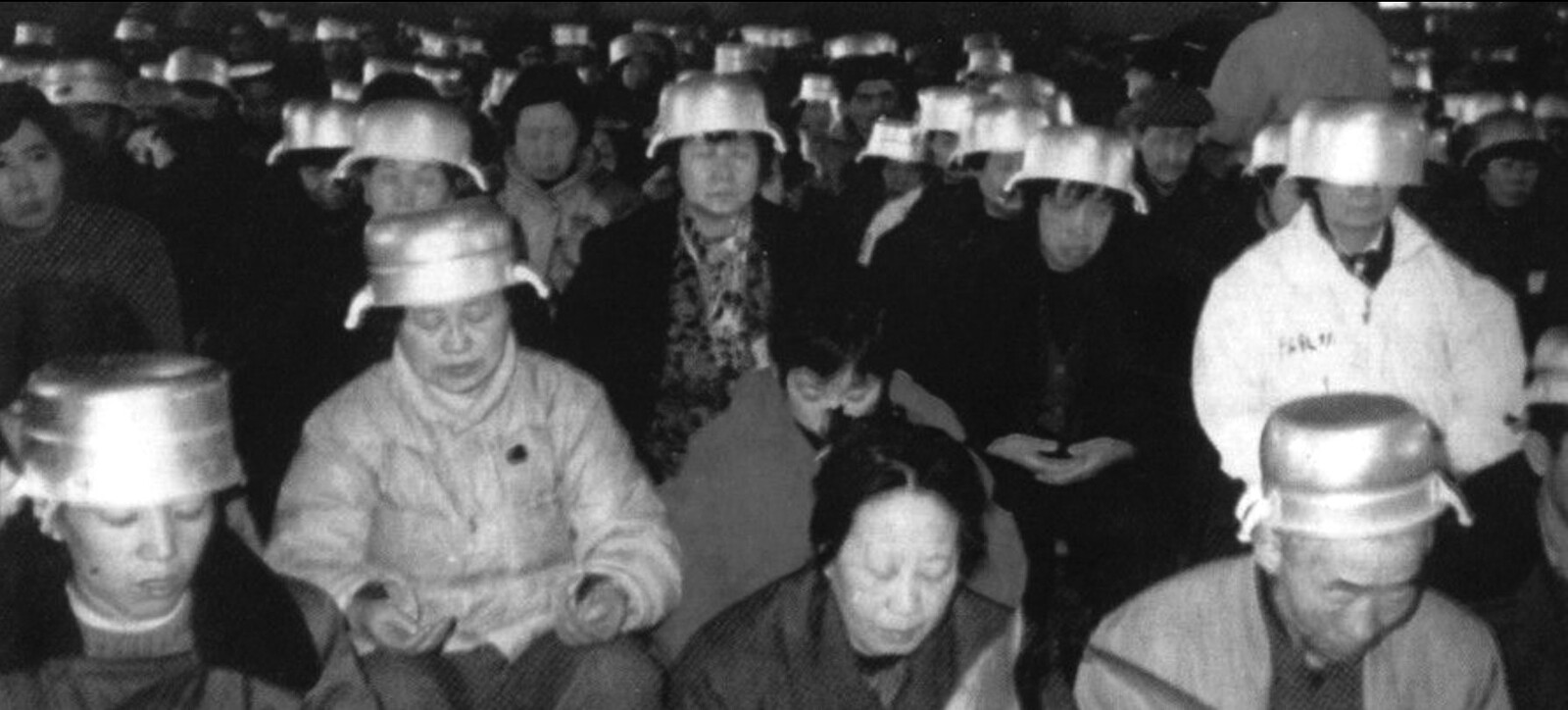

The human body as a medium is not a new phenomenon. Traditional Chinese philosophy and religious practices, as well as spiritualism in the nineteenth century, had featured different versions of the body-as-a-medium within different epistemological modes. The increasingly pervasive computational environments bring the human body to the center of current media studies, especially in the new media scholarship on digitization and networks. But the emergence of an “information body”—the body as a medium for information processing—in China in the 1980s, on the one hand, registered the ways in which contemporary media technologies transform the perceptions and interactions of the human body with the world, and, on the other hand, was a discursive construction deeply entrenched in the politics of the postsocialist world, accompanying the production and unleashing of consumer desire in the process of marketization, and concurrent with the privilege of “information workers” over factory workers and peasants, who were once valorized as socialist subjects. This “information body,” however, is not merely a passive receiver or transmitter of information.

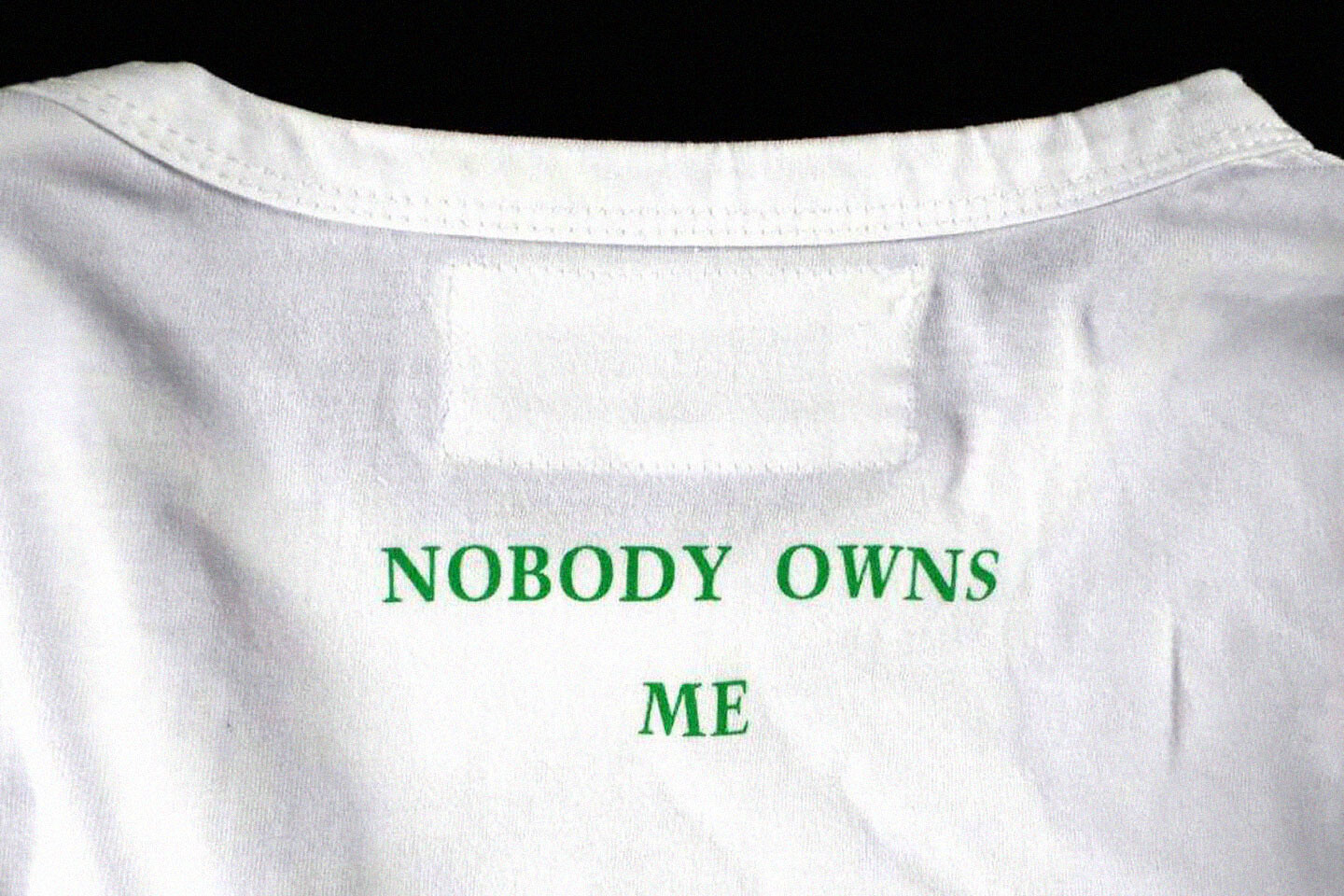

“How can we talk about private events,” Gonzalez-Torres asked, “when our bodies have been legislated by the state? We can perhaps talk about private property.” Among the most pervasive idioms for describing Americannness, private property held further implications for artists whose national and ethnic origin, racial background, and sexual orientation compromised their acceptance as Americans. As one of the few domains where cooperation occurred regardless of political preference or personal identity, the market held untapped potential as a political site. Deeply aware of how precarious life was for an openly gay, nonwhite artist living with AIDS, yet adamantly unwilling to capitalize upon his identity by wearing a metaphorical “grass skirt,” Gonzalez-Torres stated it was “more threatening” that “people like me operate as part of the market.” Through certificates that embodied rather than represented ownership by metabolizing elements of copyright and contract, he navigated market conditions and art-world protocol. Eventually shifting his works away from the metrics of supply, Gonzalez-Torres recast them as dynamic sources of doubt according to the legal frameworks to which he and they were unavoidably subject.

But what does vulnerability actually mean? Is it being able to acknowledge a state of pain or insecurity, embracing the feeling of coming undone? I feel that it’s something I’ve tried to hide from others and from myself. At the cost of headaches, a bloated stomach, the inability to articulate a sentence. A mental-physical feeling of paralysis. I now suspect that people spend a lot of time and effort hiding in this way. Could I overcome my terror of falling apart if I allowed myself to rely on others, on you? Or should I be a “cruel optimist” and create hopeful and positive attachments, in full awareness that they will not work out?