Laps are uncertain places: they consist of a corporeal configuration with no bodily matter inside the space they create, only form. The lap isn’t an organ, a limb, or a joint; the lap isn’t even a fixed cavity like the mouth, the navel, or a nostril. In being a hollow area, laps could be compared to the axillae, but armpits are still there when a person stretches or raises their arms, while there is no specific body part that is only and always attributed to the lap: when you sit, you make a lap; when you stand up, the lap is gone.

Gabriël Metsu, Het zieke kind (The Sick Child), c. 1664–66. Oil on canvas.

Laps have ambivalent meanings. As a concept, laps are where care and burden walk, or sit, hand-in-hand. Luxury and subservience coexist in the lap, where fixed lifelong roles of giving and taking are rehearsed and first enacted. A brief look at how the lap appears in a handful of English idiomatic expressions attests to this disparity. If “to drop a weight in someone’s lap” means to give a person an unforeseen responsibility, “to fall into one’s lap,” on the contrary, stands for receiving something without any effort. An individual can only hope for the positive outcome of an unpredictable fate if their situation is “in the lap of the gods”; by contrast, “to live in the lap of luxury” means to thrive in great comfort and wealth. A person sits down when they “make a lap,” but they can rightly be called “a lapdog” if they act in a subservient manner. Likewise, to “take a lap,” often said in the context of sports and just as often a punitive measure, is physically undertaken by someone on the bottom of a hierarchical relation. Lapping, an activity shared by all dogs, lap- and non, has a different meaning but a common etymology: fthe Germanic term læppa, a piece of cloth folded to keep things inside it. Just like the bended tongue of an animal lapping.

The charged and, arguably, intangible space of the lap as a site can host the promise for a new condition of intimacy, one embedded in a different set of biopolitical, cultural, and gendered imaginations.

A 1967 advertisement claims the Smith-Corona Electric Portable typewriter is “the thing with teenagers who want to swing college. Not the sit-in. Or the be-in. The type-in.”

From Lapdogs to Lap Dances

Over the centuries, the lap has been a space where primates—humans and non—have gotten closer to other people and animals. Yet, starting in the last decade or so of the twentieth century, the lap became the support for another vital form: the portable personal computer, commonly known as the laptop, whose invention, subsequent commercialization, and widespread distribution opened the lap to a new set of relationships and activities. If until then the lap was mostly a holding device (a place to sit for children, other adults, and pets), with the introduction of the laptop, the lap was turned into another support structure, its function becoming closer to a table.

But it might be worth slowing down and going back to the beginning. The lap can be made to hold and support another individual, a child, an animal, but also an adult. It is one of the primordial figures of motherhood and also of the dutifulness associated with it: the artistic canon of the pietà (the representation of the Virgin Mary holding the body of her dead adult son) provides a good example of how the lap stands for the dutifulness (and indeed, “pietà” means “dutifulness”) of motherhood during the entire life of the offspring.

David Adolph Constant Artz, In Slaap Gesust (Lulled to Sleep), 1871. Oil on canvas.

Long before the company of the laptop, another companion species had already made its way to the laps of people in all classes and genders of society: the lapdog. Lapdogs aren’t a specific breed but a generic term for a type of dog with a relatively small size and a friendly disposition. Lapdogs are tertiary-sector service workers: they are neither employed to support agrarian tasks (like herding and hunting), nor to assure the security and protection of their owners. Instead, their main function is to provide companionship. They are also a useful garment complement, providing warmth and softness, and a hygienic device, drawing parasites such as fleas and ticks away from humans. Anatomically, lapdogs show distinct differences from their full-sized counterparts. The average skull of a lapdog is approximately the size of a table-tennis ball; lapdogs generally have a short muzzle and high forehead, as they have been bred to retain juvenile characteristics, a phenomenon known as neoteny (also characteristic of humans).1 The potential inconvenience of this transformation could be summed up by the Latin expression multum in parvo, or “a lot in a little”: a great deal of dog compressed in a small creature with the propensity for a nervous, agitated, and loud character. The body proportions of such dogs have also been human-changed to retain juvenile characteristics, resulting in animals with relatively short legs and large heads. Many lapdogs have also acquired traits that resemble those of human babies, such as their overall size and weight, and their high forehead, short muzzle, and large, engaging eyes. Although selective breeding for such traits has detrimental effects on a dog’s tear ducts, dentition, and breathing, and may cause such conditions as encephalitis (a lethal inflammation of the brain and meninges), these features also increase the owners’ bonds with their animals, promoting an attitude of caring due to the dog’s similarity to a surrogate infant—cruelty and caring being impossible to disentangle.

Sidonie Gabrielle Claudine Colette, better known simply as Colette, poses with her dog, Souci, c 1930s.

While it is undeniable that lapdogs helped to shape the conduct and symbolism of a leisure- and pleasure-prone bourgeoisie, and were the object of transference of public and domestic libidinal drives, they also supported fundamental gender struggles, as noted by Paul Preciado in a text featured in a footnote to Donna Haraway’s 2008 book When Species Meet (a text that very much deserves to be republished and further developed):

Fabricated at the end of the nineteenth-century, French bulldogs and lesbians co-evolve from being marginal monsters into becoming media creatures and bodies of pop and chic consumption. Together, they invent a way of surviving and create an aesthetics of human–animal life. Slowly moving from red-light districts to artistic boroughs all the way to television, they have ascended the species pile together. This is a history of mutual recognition, mutation, travel and queer love … The history of the French bulldog and that of the working queer woman are tied to the transformations brought on by the industrial revolution and the emergence of modern sexualities … Soon, the so-called French bulldog became the beloved companion of the “Belles de nuit,” being depicted by artists such as Toulouse Lautrec and Degas in Parisian brothels and cafes. [The dog’s] ugly face, according to conventional beauty standards, echoes the lesbian refusal of the heterosexual canon of female beauty; its muscular and strong body and its small size made of the molosse the ideal companion of the urban flâneuse, the nomad woman writer and the prostitute. [By] the end of the nineteenth century, together with the cigar, the suit or even writing [itself ], the bulldog became an identity accessory, a gender and political marker and a privileged survival companion for the manly woman, the lesbian, the prostitute and the gender reveler [in] the growing European cities … The French bulldog’s survival opportunity really began in 1880, when a group of Parisian Frenchy breeders and fans began to organize regular weekly meetings. One of the first members of the French bulldog owners club was Madame Palmyre, the proprietor of the club “La Souris” located in the lower reaches of Paris in the area of “Mont Martre” and “Moulin Rouge.” This was a gathering place for butchers, coachmen, rag traders, café owners, barrow boys, writers, painters, lesbians and hookers. Lesbian writers gathered together with bulldogs at La Souris. Toulouse Lautrec immortalized “bouboule,” Palmyre’s French bulldog, walking with hookers or eating at their tables. Representing the so-called dangerous classes, the scrunched-up faces of the bulldog, as those of the manly lesbians, were part of the modern aesthetic turn. Moreover, French writer Colette, friend of Palmyre and customer of La Souris, would be one of the first writers and political actors to be always portrayed with her French bulldogs. By the early 1920s, the French bulldog had become a biocultural companion of the liberated woman and writer in literature, painting, and the emerging media.2

The extension of the overlaying functions of caring and intimacy on the lap can also be observed in the public appearance of the lap dance—a type of erotic performance in which a dancer, typically a woman, establishes physical contact with a seated client (the lap dance normally involves a monetary transaction), generally for the duration of a song, and in the setting of a nightclub.

_Luke_FildesWEB.jpg,1600)

Lap dances as a form of entertainment have a relatively recent history. They started in the 1970s in New York’s Melody Theater, with the introduction of what the venue described as “audience participation.” Subsequently, lap dances became popular in the UK between the late 1990s and the early 2000s. There is a whole history to be written on the relation between the growth of the popularity of the lap dance and the structuring of manly individualism during late capitalism.

This bilateral development is not disconnected from the creation and widespread use of the chair, whose history, as highlighted by Francis McKee, “is also closely aligned to the emergence of the individual human subject in the eighteenth century.” He continues:

Previously benches had been the main form of seating, emphasizing communality and shared space. The rise of the capitalist subject in Europe was marked by the creation of private space, the acknowledgement of individual ego and the expression of the unique self through consumer objects: the chair became a quiet symbol of this social transition.3

In later centuries, the lap dance appeared to provide the necessary reassurance of the status quo of the powerful individual male and his seated position, in which work, wealth, and pleasure converged.

According to the tagline for the 2014 film Lap Dance (dir. Greg Carter), “Fast money comes at a dangerous price.”

Affects, contemplations, stimulations, and struggles happen in and through the lap, this site that accumulates the contexts of motherhood (associated with the womb and with the bodily grammar of caring), sexual entertainment (the lap as a space where two bodies come closer through a clientele dynamic), and domesticity (the pet dog as an extension of the family sphere, a receiver of libidinal transferences, and as sublimator of privately occurring sexual drives). The lap constitutes a space at once para-sexualized—where the relation between the mother and the child, the caretaker and the cared for, takes place—and a space at the core of the unfolding of a relation of intimacy, as the lap opens itself to both male and female sexual organs, with potential physical consequences for its beholders.4 The significance and potential of this accumulation of functions in this space that is at once intimate and public opens itself, when the laptop arrives, to a new configuration.

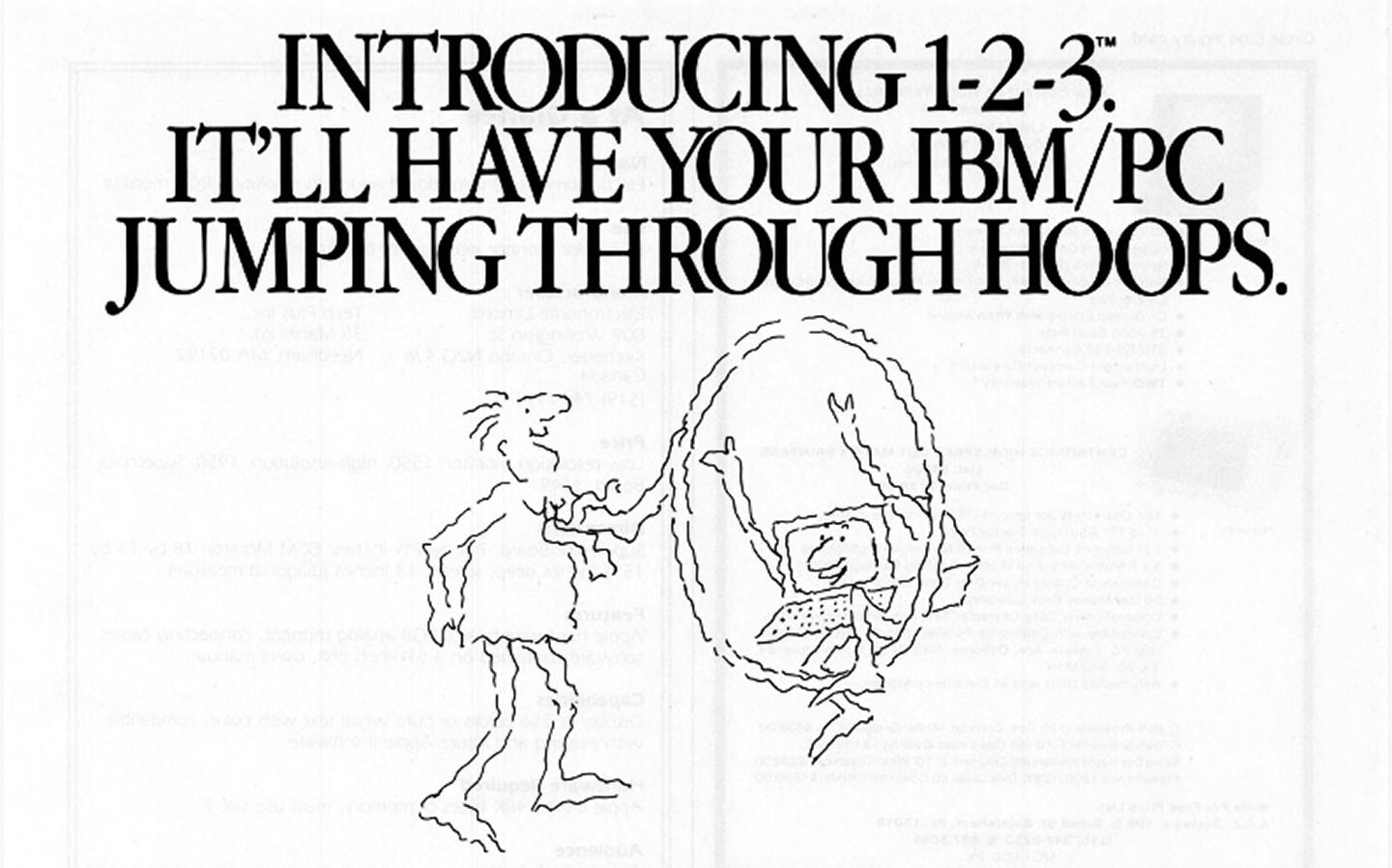

The 1-2-3™ system by the Lotus Development Corportation boasted of combining information management, spreadsheet, and graphing functions in one software package. This advertisement for the software appeared alongside competing advertisements in a 1983 edition of InfoWorld, The Newsweekly for Microcomputer Users.

Computing Intimacy

The early 1980s saw the patenting of some of the first ever portable computers, namely the Epson HX-20, registered in July 1980 by the Japanese company Seiko and introduced in the United States in 1981; the Osborne 1, patented in 1981 by the Silicon Valley company Osborne Computer Corporation; the Tandy Model 100, registered in 1983 by the Japanese multinational Kyocera Corporation; and the Gavilan SC, created by the Gavilan Computer Corporation, also based in Silicon Valley. The Gavilian SC was the first handheld computer to be named a lap computer, or a “laptop” (a term used to establish an analogy with the desktop).

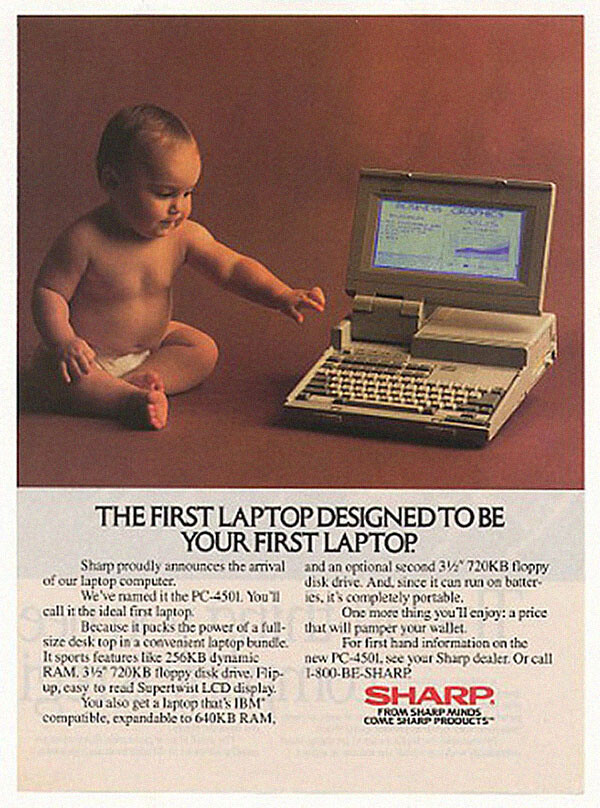

In this vintage Sharp computer ad, baby and laptop are posititioned side by side.

By being called a laptop, the handheld computer knows it can be taken everywhere. It can leave the office space and initiate a colonization of private and domestic environments, widening the ubiquitous and remote possibilities of office work. It also knows where to sit. It demands to be positioned in a space that, until its arrival, was largely dedicated to specific tasks of bodily intimacy, to domestic and/or intimate functions and transactions. This new form of contact, introduced by the computers that sit within a space of the human body traditionally associated with care, opens the path for a rethinking of the ways intimacy is conceived, thought, described, and enacted. Such a redefinition of intimacy, expressed in a verbal and nonverbal eloquence, has the potential to reshape forms of sociability and individuality across private, public, and hybrid spheres. Could the laptop support and lead its users to go beyond what Lauren Berlant defines as “the ongoing present [which] is also the zone of convergence of the economic and political activity we call ‘structural,’ by suffusing the ordinary with its normative demands for bodily and psychic organization”?5 Could it redefine intimacy by bypassing plain reproductions of normative attachments and encoded representations, and in doing so, contribute to surpassing the biases that still dominate the norms of intimate relations and the individual (gendered?) roles within them?

Laptop, worker, baby, and LapBaby™—together at last.

To think about the lap in the era of computational transformation means to think about intimacy (about intimacy as a memory and as a promise of a future). And to think about intimacy means to consider the institutional coding of relationships that unfold across the politicized space that bonds intimacy to public life.

This discourse considers, of course, the inception of handheld digital devices. Today the laptop is accompanied by even smaller and more portable devices—pads, phones, watches, glasses that are miniaturized computers, progressively smaller, lighter, faster, more nervous and responsive, retaining the childish features of their larger versions (entertainment options, rounded features, colorful displays, insistent notifications that demand immediate attention). It might even be that the laptop, diffused ten years after the proliferation of the lap dance, established yet another quasi-sexual relation with its users, which probably dethroned the lap dance as a source of excitement. What happens when this device literally jumps into our lap and positions itself in an area of the confluence of affective and sensual pleasure?6 What does it generate and how does it affect individuals? A more classical position would maintain that, by locating itself in the lap, the personal computer took over the ultimate intimate and particularly feminine site. In this reading, the agencies behind this device and its uses claim this space for themselves, rendering it yet another site of exploitation and further propagating the existence of domestic, immaterial, unpaid, invisible caring labor. Hence the laptop would contribute to further consolidating gender roles, as the lap becomes a working platform and environment: from domestic labor to participating in the system of global, corporate trade.

With the widespread adoption of the laptop, the lap is no longer just a site of intimacy for the labor of care, where life is brought closer; it is also the place from which thoughts, ideas, affects, calculations, and all sorts of transactions are disseminated far and wide: “From my lap, with love,” could be the signature of an email sent from a laptop.

This 1982 advertisement for an early tablet says that the Epson Hand-Held-Computer HX-20 is the computer that goes along on the trip.

Conclusion

Relations and positions change; normative configurations call for reinvention; a whole new assemblage of interpersonal and transpersonal dynamics is set in motion, one in which the biology of the human body becomes but one factor in defining a species, a gender, a skin. In this new context, it is possible to learn to create different social bonds, to invent new structures other than families and hierarchies to negotiate affects, experiences, and positions. And this happens not only through a new rhetoric, but first and foremost by considering the new material conditions that reshape it. The material conditions for such reconfigurations emerge not in bodies, not in minds, not in atomized individuals who hold their computers on their laps, but across, in between people. As Tim Ingold asks,

What if we were to think of the person … not as a blob but as a bundle of lines, or relations, along which life is lived? What if our ecology was of lines rather than of blobs? What then can we mean by “environment”? People, after all, don’t live inside their bodies, as social theorists sometimes like to claim in their clichéd appeals to the notion of embodiment. Their trails are laid out in the ground, in footprints, paths and tracks, and their breaths mingle in the air. They stay alive only as long as there is a continual interchange of materials across ever-growing and ever-shedding layers of skin.7

The location of the personal computer in the lap can become an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone—to think about how both conventional identity politics and traditional notions of embodiment might be reformed with this pairing of the handheld computer and the lap. What I’m proposing here is that a device that combines hundreds of functions and possibilities, a device that is meant to sit on laps, has the capacity to redefine the relations to those political positions that rely on a sense of belonging and on the perception of the relevance of what happens within individual, enclosed bodies. What else is changing now that we communicate, write, read, photograph, record, calculate, predict, buy, learn, think, travel, play, love, cry, and laugh from our laps—now that our laps have become the place where such disparate elements as the cosmos and cosmetics meet?

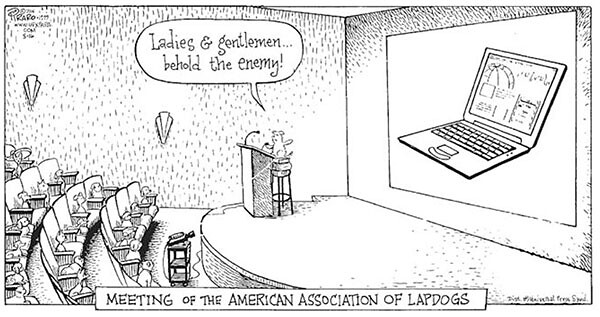

In this 1999 comic by Dan Piraro, lapdogs unite against their lap-rivals.

As intimacy develops new norms and new channels, novel personal, collective, political, and social configurations are emerging. New modes of attachment are being established across persons and collectivities, traversing public and intimate spaces; they are arising from this new presence in our laps, a presence that allows for the discovery of less normative, less binary selves. These modes also allow us to rethink, with Berlant, “intimacy in terms of what we have been and how we have lived in order to imagine lives that make more sense than the ones so many are living.”8 By claiming a privileged space of affective dynamics—the lap—and turning it into a stage for the redefinition of who we are and how we are, this presence has the potential to denaturalize canonical relations and conceptions, bringing us to conceive of our selves as “intricately enmeshed relations rather than the (classical one) divided into discrete and autonomous entities.”9

Neotenic features in lapdogs include soft, folded ears, short muzzles, and playful and docile traits. See for instance Stephen Jay Gould, “A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse,” The Panda’s Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History (W. W. Norton & Company, 1992), 95–107.

Donna J. Haraway, When Species Meet (University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 303–04.

Francis McKee, “Martino Gamper’s ‘Middle Chair,’” art agenda, July 25, 2017 →.

See for instance the scientific paper, published by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, by Conrado Avendaño, Ariela Mata, M. S., César A. Sanchez Sarmiento, and Gustavo F. Doncel, “Use of laptop computers connected to internet through Wi-Fi decreases human sperm motility and increases sperm DNA fragmentation,” Fertility and Sterility 1, vol. (January 2012): 39–45 →.

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Duke University Press, 2011), 17.

It might also be worth noting that the German term for lap, “Schoß”—hence “Schoßhund” (lapdog) and “Schoßkind” (spoiled child)—can also be used to refer to the female sex organs.

Tim Ingold, “From science to art and back again: The pendulum of an anthropologist,” ANUAC 1, vol. 5 (June 2016): 8.

Lauren Berlant, “Intimacy: A Special Issue,” Critical Inquiry 2, vol. 24 (Winter 1998): 286.

Ingold, “From science to art and back again,” 8.