1.

A biologist enters mysterious territory on a mission to comprehend the incomprehensible. Together with three colleagues—an anthropologist, a psychologist, and a surveyor—she crosses an imperceptible border into a region known as Area X. They are the twelfth expedition to cross the border. They are all women.

Jeff VanderMeer charts Area X’s impossible terrain in his Southern Reach trilogy. The first book of the series, Annihilation, flirts with various genre conventions but warps and refracts them. Most often, VanderMeer is cited as a foremost writer of the New Weird, which, in the tradition of Lovecraftian Old Weird, deals with the wonder and horror at the fringes of human consciousness. Others have called his work “soft” science fiction—the natural world being the primary site of speculation rather than technology—and some talk about it in the context of “cli-fi,” or climate fiction: narratives reflecting the transformations of the drastically changing planet.1

Annihilation’s narrator is the unnamed biologist. An expert in “transitional ecosystems”—regions where one biosphere meets another—she has trained with her colleagues for months to prepare for their journey into Area X. The region itself is a wide parcel of coastal land “locked behind the border” thirty years prior, following an “ill-defined Event.”2 The exploratory expeditions over decades past, organized by an opaque bureaucracy called the Southern Reach, have failed to bring back comprehensible data. Few groups have even returned. The general public has only been told that an ecological disaster has rendered the area uninhabitable. In fact, the biologist’s group quickly discovers the opposite is true: the landscape is, as the characters repeatedly describe it, “pristine.”

An unidentifiable agent is transforming the terrain in Area X, somehow reversing or erasing human influence on the landscape. This agent is most readily explained—and is usually interpreted—as an alien life-form. In this regard, Annihilation accords with the classic science fiction premise of First Contact with the alien other. But, as one reviewer writes, “VanderMeer takes this idea to the extreme, suggesting that we may not, on an ontological level, even be able to comprehend an alien form, that it could be so different and vast as to warp our sense of reality and reason.”3 Beyond any specific alien, the subject of Annihilation is a more profound kind of unknowability.

From this perspective, VanderMeer’s New Weird is to science fiction what mysticism is to theology. Like mystical texts throughout the ages, his Weird does not explain; it attempts to get at something beyond the explainable. Mystics of the Judeo-Christian tradition—who flourished especially during several centuries of the Middle Ages—were similarly preoccupied with a kind of First Contact; for them, this was contact with divine presence, leading to transcendence of earthly self.

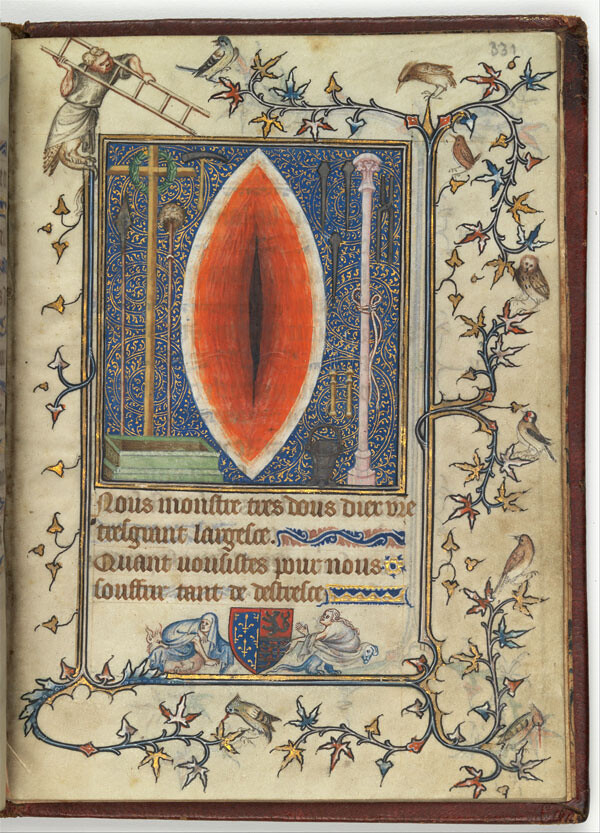

Attributed to Jean Le Noir and Workshop, The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy, date c. 13th century, France. 69.86 Photo: The Cloisters Collection, 1969.

Many foundational mystical texts in this lineage have been written by women. In the Middle Ages in particular, women’s access to theological knowledge (the explanation and interpretation of sacred texts) was limited by circumstance. Therefore the knowledge about God they produced was often empirical in the most literal sense: a kind of truth only obtained by firsthand, affective experience. Although not necessarily opposed to the religious theory or conventions of their time, given the radical authority implied by their often intimate communion with God, female mystics have at various points posed political threats to religious institutions; in these cases mystics become martyrs.

Together their writings amount to a lineage of female knowledge outside of dominant epistemologies of both religion and science. Their insistence on the possibility of encounter beyond reason—even beyond what the conscious mind can account for—is, weirdly, comparable to the type of revelation Annihilation proposes. As a literary category, New Weird holds potential to unearth and update mysticism according to contemporary knowledge, much of which points to an existential threat on the species level. In Western mysticism, the transformational (alien) force beyond the limits of human consciousness was God. In Area X, maybe the divine is literally alien, or maybe it’s simply nature at its most ecstatic, matter at its most vibrant, the nonhuman at its most alive—so alive it annihilates not only a single human self but the category of human altogether.4

Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas [detail], 1601–1602. Oil on canvas. Sanssouci Picture Gallery. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

2.

In The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James writes that the term “mysticism” is often used synonymously (and derisively) with the vaguely spiritual, the illogical, or the romantic. Yet, although the mystical may be ungraspable and inexpressible, James argues that true mystical experiences are not at all opposed to “facts or logic” and, when taken as a consistent phenomenon throughout history, are not entirely ambiguous or undefinable. He proposes four hallmarks by which to identify a mystical experience:

1) Ineffability: “its quality must be directly experienced; it cannot be imparted or transferred to others.”

2) Noetic quality: the state may be highly affective, but it is primarily a state of knowledge, whereby one achieves “insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect.”

3) Transiency: it is fleeting and impermanent.

4) Passivity: the subject does not have the power to induce it or control its course.5

James readily admits that mystical states may be brought on by external agents (alcohol and ether, for example), disorders like epilepsy, or mental illness, yet he refuses to reduce them to delusion, as many rationalists were wont to do. Neither can they be reduced to the religious contexts in which they often take place; religion has historically provided a framework within which to interpret mystical revelation—harnessing mysticism’s power when it suits the religious order and denouncing it as heresy when it doesn’t—but to James its persistence proves that it extends far beyond what institutionalized religion can account for.6

James quotes a variety of literature containing accounts of what he identifies as mystical experiences. Along with saints and theologians, who may be predisposed to accepting divine mystery, he cites psychiatrists reckoning with whether and how to rationalize mystical states. For instance, British psychiatrist Sir James Crichton-Browne observed recurrent “dreamy states” in patients: “the feeling of an enlargement of perception that seems imminent but which never completes itself”—he believed these were a precursor to insanity.7 Canadian psychiatrist R. M. Bucke, on the other hand, documented his own lapses into “cosmic consciousness,” which he did not think required medical intervention, presumably because he had experienced them himself. (James does not examine the gendered aspect of medical evaluations—he does not ask whose mystical states psychiatrists are more likely to pathologize.)8

Bucke described his cosmic experiences as an evolutionary process toward a higher state. “Along with the consciousness of the cosmos there occurs an intellectual enlightenment which alone would place the individual on a new plane of existence—would make him almost a member of a new species.” These experiences often struck him while he was alone in nature. “I saw that the universe is not composed of dead matter, but is, on the contrary, a living Presence.”9

3.

Soon after crossing the border, the biologist and her companions begin to encounter unexplainable phenomena. A strange tunnel into the ground unmarked on the map. Eerie howls from the forest at dusk. An overgrowth of plants incongruous with the amount of time that has passed since the border was sealed. Gaps in time, amnesia. A pair of otters in the marsh staring at them for a little too long. A dolphin in the river whose eye looks shockingly human. They begin to lose trust in their own perceptions. In the biologist’s words: “What can you do when your five senses are not enough?” 10

The tunnel is particularly confusing and compelling to the four explorers, and the biologist is drawn to enter it. Despite what she sees, she insists on describing the tunnel as a “tower.” She admits she can’t explain why she thinks of it this way, but she’s unable to conceive of it otherwise: to her it is an inverted tower, an entry in the earth that one must, paradoxically, ascend. She says, “I mark it as the first irrational thought I had” in Area X.11

As they begin to foray down, the explorers discover a succession of words lining the circular wall of the tunnel/tower. The text itself, which VanderMeer recounts having written in one stream of consciousness after waking from a dream, turns out to be alive. Each letter of each word is composed of a sort of fungus that releases tiny spores into the air—spores that the biologist accidentally inhales. “I leaned in closer,” she says, “like a fool, like someone who had not had months of survival training or ever studied biology. Someone tricked into thinking that words should be read”12 She reads the words, but (until she finds a respirator) the act of reading is also an act of ingestion.

The biologist descends/ascends the stairway several times over the course of the book, each time penetrating deeper/rising further and consuming more of the words. The scripture reads:

Where lies the strangling fruit that came from the hand of the sinner I shall bring forth the seeds of the dead to share with the worms that gather in the darkness and surround the world with the power of their lives … In the black water with the sun shining at midnight, those fruit shall come ripe and in the darkness of that which is golden shall split open to reveal the revelation of the fatal softness in the earth. The shadows of the abyss are like the petals of a monstrous flower that shall blossom within the skull and expand the mind beyond what any man can bear … All shall come to revelation, and to revel, in the knowledge of the strangling fruit—and the hand of the sinner shall rejoice, for there is no sin in shadow or in light that the seeds of the dead cannot forgive … That which dies shall still know life in death for all that decays is not forgotten and reanimated it shall walk the world in the bliss of not-knowing. And then there shall be a fire that knows the naming of you, and in the presence of the strangling fruit, its dark flame shall acquire every part of you that remains.

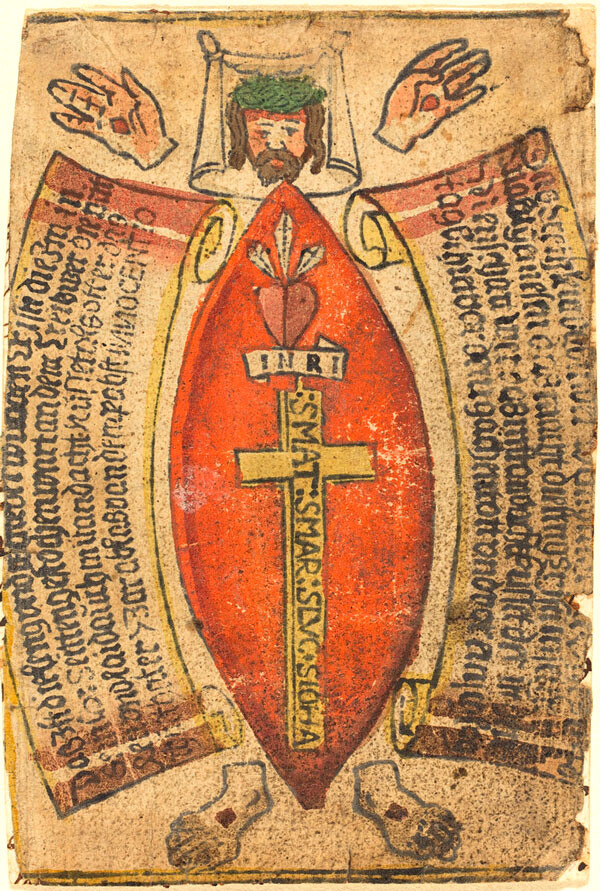

The Wounds of Christ with the Symbols of the Passion, c. 1490. Woodcut, hand-colored in vermilion, green, and yellow on paper; Mounted on sheet of paper that covers manuscript on verso. Schreiber, Vol. IX, no. 1795, Rosenwald Collection 1943.3.831 Photo: National Gallery of Art, United States.

4.

The Mirror of Simple Annihilated Souls is a mystical text written in the latter half of the thirteenth century by the French-speaking beguine Marguerite Porete. The book, part prose and part poetry, is a meditation on divine love as well as a kind of mystical manual. It describes the seven stages of an “itinerary”—“the steps by which one climbs from the valley to the summit of the mountain, which is so isolated that one sees nothing there but God.” These stages, the final of which can only be reached after death, represent various degrees of self-annihilation: the stripping away (aphairesis) of the will to make way for God. “So one must crush oneself,” writes Porete, “hacking and hewing away at oneself to widen the place in which Love will want to be.”13

Such exponential self-negation entails a host of contradictions. How to will away the will? How to desire away the self that desires? How to author a text on the negation of the self who writes the text? According to the poet-essayist Anne Carson, the fundamental relationship between the mystic and the written word “is more than a contradiction, it is a paradox.”14 Writing a mystical text is an inherently futile practice (as is reading one). The writer has no choice but to use language to express the failure of language. Porete “calls for the annihilation of desire itself, which entails a movement past mediation, contemplation, rapture, and loving union into the abyssal negation of the soul.”15

Porete’s work is a prime example of mystical writing in the apophatic tradition. Apophasis: the rhetorical strategy of approaching a subject by denying its existence, or denying that it can be described. The foundational apophatic writer in the Christian mystical tradition was Dionysius the Areopagite, who stated in the fifth or sixth century that only “by knowing nothing, one knows beyond the mind.”16 Six centuries later, Meister Eckhart, influenced by Dionysius and likely by Porete, described God as the “negation of the negation.”17

Apophasis, the via negativa, is an all-out confrontation with linguistic futility in the presence of the unknowable. Its rhetorical counterpart is cataphasis, the via positiva: the strategy of endlessly asserting what a subject is, in order to arrive there through sheer (perhaps infinite) accumulation. Whereas the apophatic might say “God is the absence of darkness,” the cataphatic might say “God is the sun, the ultimate light.”

Eugene Thacker describes the cataphatic as a set of “descending assertions” and the apophatic as a set of “ascending negations.”18 The former strategy builds up to nothing, whereas the latter strips away to nothing. That is, the impossible tower toward the impossible goal can be constructed either by stacking stones forever downward or removing stones forever upward. The tower is the tunnel is the tower. According to Dionysius, “there is no contradiction between the affirmations and the negations, inasmuch as [God is] beyond all positive and negative distinctions.”19

5.

Soon after inhaling the spores spewed from the “fruiting bodies” of the fungal text, the biologist begins to notice that her senses are heightened. “Even the rough brown bark of the pines or the ordinary lunging swoop of a woodpecker came to me as a kind of minor revelation.”20 Venturing further into the (un)natural landscape, she experiences flashes of the joy of discovery and oneness with nature that she hasn’t felt since she was a child. Eventually this intensification of experience becomes manifest in her body, a feeling of phosphorescence, a “brightness” in her chest. Now, when she enters the tower, she feels like the structure is breathing, that the walls are “not made of stone but of living tissue.”21 She refers to this perception as a kind of “truthful seeing.”22 “Everything was imbued with emotion, awash in it, and I was no longer a biologist but somehow the crest of a wave building and building but never crashing to shore.”23

As a scientist, she knows that there are plenty of rational explanations for her sensory expansion: “Certain parasites and fruiting bodies could cause not just paranoia but schizophrenia, all-too-realistic hallucinations, and thus promote delusional behavior.”24 She almost hopes to discover that one of these explanations is true; however unfortunate, insanity would be a known quantity, a logical justification for the words and their effect. The narrator says: “Even though I didn’t know what the words meant, I wanted them to mean something so that I might more swiftly remove doubt and bring reason back into all of my equations.”25 Attempting to understand, she examines spore samples under a microscope, finding that they are unusual but “within an acceptable range” of abnormality.26 Area X, it seems, is not entirely opposed to empirical observation, but it can’t be explained by it either. More to the point—she realizes that, now contaminated by her subject, she is no longer a reliable observer. She is melding with the ecosystem she observes.

6.

In 1373 the English anchoress, mystic, and theologian Julian of Norwich (c. 1342–1416) received a series of mystical “showings.” She had been suffering for days from an illness that she was sure would kill her, when she was suddenly relieved of her pain and God showed her several “nothings.” Julian’s nothings could be understood as apophatic visions, visions that in their revelation also reveal the futility of sight. In addition to psychedelic-seeming close-up visuals of Christ’s wounds and of Mother Mary, she also saw “a little thing, the size of a hazelnut in the palm of my hand, and it was round as a ball.” When she asked what the little thing was, God answered: “It is all that is made.”27

Norwich recorded these visions and others in her book Revelations of Divine Love (1395), the first known book written in English by a woman. Throughout the text she refers to her divine perception as a kind of “bodily sight.” At times she contrasts this corporeal vision to “spiritual sight,” suggesting a knowledge that can only be acquired through firsthand physical perception—and yet this perception is not solely of the eye or the other senses. It is a kind of seeing that is also a feeling and a knowing.28

The Italian Franciscan Catholic mystic Angela of Foligno (1248–1309) had her own series of visions, including several vivid encounters with Christ’s dead body. These visions were particularly focused on the wound in his side, the incision left by a lance between his ribs that so many medieval depictions of the Cross fixate on. In her first vision, Angela saw herself pressing her mouth to the wound and drinking blood from it. Next, she envisioned her soul shrinking and actually entering into the side of Jesus’s abdomen. Finally, she became his body, melding with his flesh, dissolving into it.29 Galatians 2:20: “It is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives within me.”

Angela did not record her divine encounters herself. She related them to her (male) scribe, who attempted to transcribe them to the best of his ability. Apparently Angela often asked him to revise sections she found unsatisfactory or inaccurate, altering the body of the text he produced to more closely resemble the experiences of her own body, in relation to Christ’s body.

If mystical encounter entails a sort of spiritual transmission, the body of the mystic is the medium that registers the message.30 The body is the primary site of inscription, and according to James’s first mystical qualifier, this inscription is nontransferrable. The body must be read in order for its knowledge to be translated as best as possible into writing; therefore “bodies—inner and outer, material and spiritual—become text.”31 In turn, the resulting written corpus must be brought alive to become like the body it’s meant to resemble. In Christianity, this twin becoming of text and body parallels Christ’s incarnation—whereupon God’s “Word was made flesh” (John 1:14).

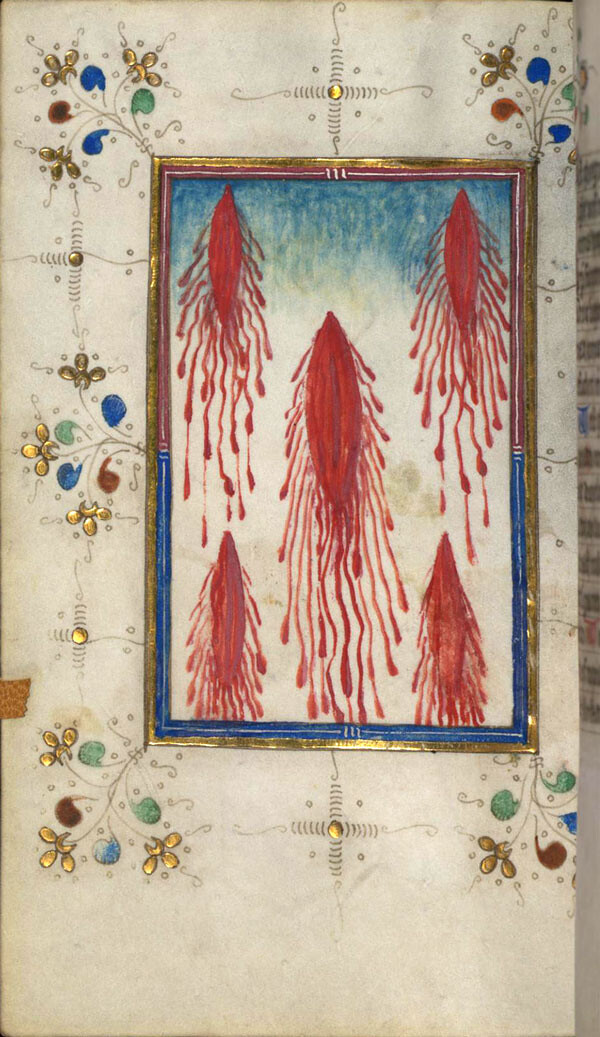

Mystical texts like Julian’s and Angela’s are often repetitive, contradictory, circular; they breathe and they beat. Reading them is interactive—it requires, as religion scholar Amy Hollywood has suggested, a sort of radical absorption on the part of the reader to mirror the self-annihilation attempted by the author.32 Medieval mystical texts often include images springing from the words, including figurative drawings of Christ and other bodies. Christ’s side wound is sometimes depicted as a separate body part, a (very vaginal) opening into the page, for readers to peer into or imagine entering. A few manuscripts depicting Christ’s corpse even represent the slit in his side as a physical tear in the paper, for the devout to fondle and kiss.33

Masters of the Delft Grisailles, Leaf from Loftie Hours: Five Wounds of Christ, mid 15th Century. The Walters Art Museum, W.165.110V, Photo: Creative Commons/CC0

7.

“I have not been entirely honest thus far,” admits the biologist fifty pages into Annihilation.34 She has withheld an important fact: her husband, a doctor, served as a medic on the previous mission to Area X. She acknowledges that keeping this secret from both the reader and her companions might seem suspicious—so why has she kept it to herself? Perhaps, she implies, because she doesn’t wish her narrative to rest on biography, dismissed as irrational or emotional from the start. Perhaps she doesn’t want her choice to risk entering Area X to be pathologized. Her husband has something to do with it all, she insists, but only something. “I have hoped that in reading this account, you might [still] find me a credible, objective witness.”35

After her husband left for Area X, the biologist heard nothing from him for a year. And then one night, out of the blue, he showed up at their home, wandering into the house unannounced. He couldn’t explain how he’d gotten back or what he’d been doing while away. His memories were vague. His body had come home, but his self, it seemed, was not present in the body; “He was a “shell, an automaton,” “stripped of what made” him “unique”.36 His body died of inexplicable cancer a few months later.

Finally given the chance to explore the transitional biosphere where her husband left his self, the biologist wonders how her experience compares to his. She discovers by accident that the enveloping “brightness” brought on by the spores can be forestalled momentarily if she injures herself; pain seems to keep it at bay. But does she want to keep it at bay? She begins to see the enveloping nature of Area X as more an invitation than a threat. Perhaps self-dissolution need not be the same as death after all. In Area X, her husband had “been granted a gift that he didn’t know what to do with. A gift that was poison to him and eventually killed him. But would it have killed me?”37

Book of Hours, end of 15th century. MS. Douce d. 19, Fol. page 077r. Photo: Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

8.

The extreme nature of the emotional and physical experiences of female mystics is often reflected through accounts of pain: its endurance and its transcendence. The repeated emphasis on the body as a site of encounter—through suffering and/or ecstasy—is simultaneous with, or makes way for, the spiritual encounter. The boundaries of the body are dissolved, and likewise is the boundary of the soul. Hollywood explains: “Throughout pre- and early modern Christianity, women were associated with the body, its porousness, openness, and vulnerability. Female bodies were believed to be more labile and changeable, more subject to affective shifts, and more open to penetration, whether by God, demons, or other human beings.” This engendered a “slide, from claims to women’s spiritual penetrability to that of her physical penetrability” and vice versa.38

The argument that there is biological basis for the female experience of being-in-world as being-with-other is not uncommon. For instance, philosopher Nancy Hartsock writes in her foundational 1980s text on the “Feminist Standpoint”: “There are a series of boundary challenges inherent in the female physiology—challenges which make it impossible to maintain rigid separation from the object world. Menstruation, coitus, pregnancy, childbirth, lactation—all represent challenges to bodily boundaries.”39

Hartsock argues further that these “boundary challenges … [take] place in such a way that empathy is built into [women’s] primary definition of self, and they have a variety of capacities for experiencing another’s needs or feelings as their own … more continuous with and related to the external object world.”40 According to such a theory, the biologically female body predicates a permeability of self and therefore a more intrinsically open and empathic relation with the world.

The body-based essentialisms and biological determinism implied by such feminist frameworks have not come without critique. Is identification with the world, however emblematic of female experience, really premised on binary body basics? Is the capacity for empathy supposedly “natural” to women not also a handy emotional technology to maintain the social class meant to do the majority of affective labor? One could just as easily argue that physical penetrability might make a person extra resistant to boundary challenges rather than inherently susceptible to them.

Hollywood, for one, focuses on deconstructing the epistemological dichotomy between male and female mysticism implied in such distinctions. The notion that women’s mystical relationships with the divine are primarily emotional/corporeal, as opposed to theological and intellectual, keeps their insight forever outside of systems of codified rational knowledge. Instead of preserving these as separate epistemological tiers, Hollywood implies, the category of what counts as empirical knowledge should be expanded. This is especially true when it comes to approaching subjects that are intrinsically unknowable, which as James points out, requires affect. The type of affective knowledge of female mystics in the Christian tradition is not counterposed to intellectual knowledge but rather makes way for a “noetic” (weird) knowledge beyond the dialectic.

9.

“What modern readers find most disturbing about medieval discussions,” writes contemporary medievalist Caroline Walker Bynum, “is their extreme literalism and materialism.”41 She recounts earnest, high-stakes debates in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries about exactly how bodies might be resurrected after death—could you be brought back from the dead from a sole surviving fingernail, or did you need to be buried whole and intact to be properly resurrected? Would fetuses be resurrected as adults? Once the body is brought back by God, will it see, smell and taste in the same way? “What of ‘me’ must rise in order for the risen body to be ‘me’?” Generally speaking: “Is materiality necessary for personhood?”42

However absurd these questions might seem today, Bynum argues that contemporary debates about the relationship between self and materiality spring from the same set of concerns. For instance, organ donors often insist that they feel a “part” of themselves living in the organ’s host body, or describe a spiritual connection to that host. Proponents of cryogenics debate whether preserving the brain is enough for future reanimation, or whether resurrection of the whole self will require the whole body. The allure and the terror of the technological Singularity, whereby humans meld with machines, indicate this deep unease. Bynum says these are not so much struggles with “mind/body dichotomies” but rather attempts to understand “integrity versus corruption or partition” when it comes to how much of you is yourself.43 (Will you be yourself when you come back from Area X?)

That idea of an integral bounded self, uncorrupted and whole, is in fact one prerequisite for what is often called sanity. “Most people feel they begin when their bodies began and that they will end when their bodies die,” writes psychologist R. D. Laing in his 1955 book on schizophrenia, The Divided Self.44 A person who experiences himself as “real, alive, and whole” is a person who Laing calls “ontologically secure,” whereas an “ontologically insecure” person possesses no such “firm sense of his own and others’ reality and identity” as distinct from one another. 45 The shadows of the abyss are like the petals of a monstrous flower that shall blossom within the skull and expand the mind beyond what any man can bear.

Understood in this way, insanity is the dystopic version of self-annihilation. When the border distinguishing the self-in-body from the environment becomes too porous, the ontologically insecure person encounters nonbeing as pure horror. But for mystics, especially non-male mystics, this kind of willing self-corrosion is exactly the premise for divine contact and transcendence. The mystic finds joy in the dissolution of self—its “corruption or partition” on the way to nothingness. The insane person fights tooth and nail to retain ontological security out of fear. The mystic actively deconstructs the self in the name of love.

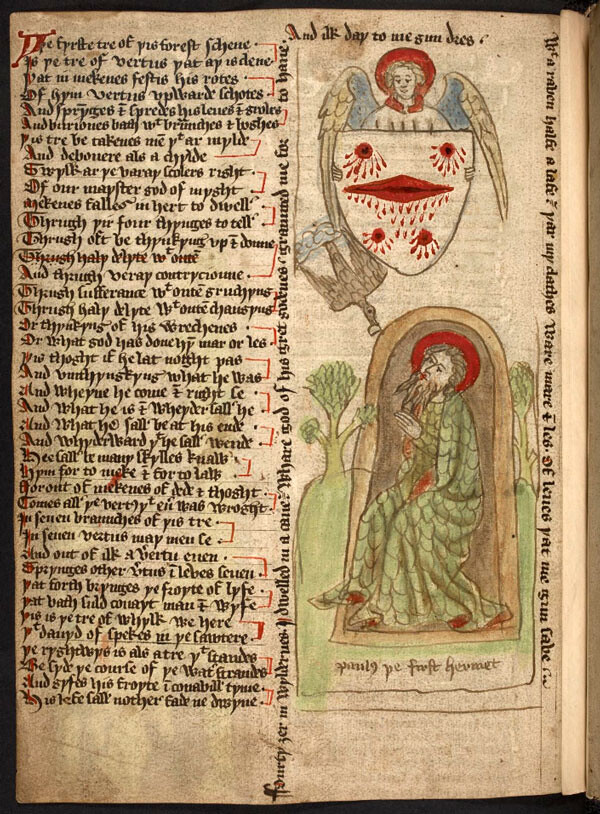

The Carthusian Miscellany (Religious Prose and Verse) in Northern English, including an epitome (summary) of Mandeville’s travels, c. 15th century. England

10.

What Marguerite Porete called self-annihilation, the twentieth-century mystic Simone Weil called “decreation.” For Weil, decreation was the endeavor to “undo the creature in us,” that is, to undo oneself, and also the self as such.46 These are two orders of negation, one specific and one general, which Meister Eckhart also differentiates between in his cataphatic expedition to God: the nothingness of particular creatures versus the nothingess of creaturely being.47 Or: the cancellation of particular existence versus the cancellation of the existence of existence. Weil, like Porete, aimed for the latter by way of the former.

Weil succeeded in surrendering herself; for most of her life she had trouble eating, and she eventually died from tuberculosis exacerbated by the inability to eat. She desired to decreate herself to the point that she could subsist without eating at all, living on words alone. “Our greatest affliction is that looking and eating are two different operations,” she wrote. “Eternal beatitude is a state where to look is to eat.”48 From Weil’s writing it appears that, for her, self-starvation was not exactly self-punishment; it was an intense sensitivity toward the suffering of others (during World War II, she reportedly refused to eat any types of food that were not also included in the allotted rations for French soldiers). Her abnegation may have amounted to a political statement, but it was primarily spurred by her pain on behalf of others: an affective and physical aversion to the consumption necessary to sustain the single self. She would not, but also could not, eat.

Chris Kraus writes, “Weil was more a mystic than a theologian. That is, all the things she wrote were field notes for a project she enacted on herself. She was a performative philosopher. Her body was material. ‘The body is a lever for salvation,’ she thought in Gravity and Grace. ‘But in what way? What is the right way to use it?’”49 As James writes, for mystics the “moral mystery intertwines and combines with the intellectual mystery.”50

It’s tempting to try and “solve” that mystery. Religion, flawed as it is, has at points throughout history offered a language for describing First Contact with the unknowable.51 In the absence of a mystical framework for dealing with the mystery, contemporary analysis tends to wind up with psychiatry. “Until recently,” argues Kraus, “nearly all the secondary texts on Simone Weil treat her philosophical writings as a kind of biographic key.” The focus remains on trying to figure out what triggered her psychiatric state rather than on her “active stance” of willful, intellectually engaged decreation and the resultant body of knowledge she produced. “Impossible to conceive a female life that might extend outside itself,” Kraus remarks. “Impossible to accept the self-destruction of a woman as strategic.”52 According to Kraus, “Weil’s detractors saw her, a female, acting on herself, as masochistic.” But Weil was, despite all dismissive diagnoses, “arguing for an alien-state, using subjectivity as a means of breaking down time and space.”53

Angela of Foligno became a mystic after the sudden death of her husband and children. One could easily interpret her necrophiliac visions in light of that biographical fact. And in historical context her sudden religious conversion could be seen as a practical choice among limited options for a single woman of that era who had lost family status and property. There is plenty to explain away her mystical encounter through the psychology of grief or the demands of her world, just as one could reduce Weil’s decreation to trauma or anorexia. Likewise, one could read the biologist’s succumbing to Area X as a parable of personal loss—or of the social condition of being a female scientist, who understands that her objective analysis intertwines and combines with her bodily sight.

11.

In an essay called “Weird Ecology,” the writer David Tompkins compares Area X to a “hyperobject,” a term philosopher Timothy Morton used “to describe events or systems or processes that are too complex, too massively distributed across space and time, for humans to get a grip on.”54 Global warming, black holes, and mass extinction are contemporary examples. For medievals: God. The mind can edge close to the hyperobject, understanding parts of it, but never comprehend its totality. Hyperobjects can certainly be measured and analyzed, but will never be encompassed by measurement and analysis. Media theorist Wendy Chun has said: “You can’t see the climate; you can only see the weather.”55 Or, as the biologist says, “When you are too close to the center of a mystery there is no way to pull back and see the shape of it entire.”56 How one longs to see it for a split second as a hazelnut-sized thing in the palm of the hand.

Faced with the possible annihilation of the planet as we know it, certain modes of knowing fall short. Especially insufficient is knowledge that purports humans to be distinct from ecosystems, much less in control of them. Among the “surprises and ironies at the heart of all knowledge production,” says Donna Haraway, is the fact that “we are not in charge of the world.”57 A mysticism for the Anthropocene, just like mysticism through the ages, would regard the “object” of knowledge as alive and inseparable from the mind and body that encounters it. That is, rather than fictionalizing science, a mysticism for today would have to Weird it.

Haraway proposes a feminist understanding of objectivity not through any single, monolithic explanation but through an assemblage of “situated knowledges” or “views from somewhere.”58 Somewhere, meaning positioned in location and historical context, and also meaning embodied—entailing a type of bodily sight. “Situated knowledges,” Haraway explains, “require that the object of knowledge be pictured as an actor and agent, not as a screen or a ground or a resource.”59 This refers to the way women have historically been seen as “objects” of study rather than active knowledge producers, but it is equally applicable in regards to the natural environment, which has so long been conceived as passive or inert. In the black water with the sun shining at midnight, those fruit shall come ripe and in the darkness of that which is golden shall split open to reveal the revelation of the fatal softness in the earth.

Simone de Beauvoir wrote that Simone Weil had “a heart that beat around the world.” Chris Kraus described Weil’s state of being as a “radical form of empathy.”60 Importantly, for the biologist in Annihilation, this empathy extends to, even prioritizes, the nonhuman. In Leslie Allison’s words: “Once the borders have dissolved, empathy is not just feeling others’ pain or pleasure. It is granting everything its own subjectivity. It is acknowledging that even non-human entities have a self with which to desire a particular way of living.”61 In Area X, the self dissolves—but self is also everywhere. Even the dolphin has a self now.

Is there a biological basis for self-annihilation? Are sex or gender prerequisites for empathic knowledge or bodily sight? Of course not. Look through a microscope: every body is permeable and porous, host to and hosted by trillions of other life-forms. The body is a transitional ecosystem; it can’t survive in a vacuum. And anyway, if we were able to stop projecting contemporary epistemologies onto the past we’d see that medieval mystical writings are too deeply weird to read according to contemporary gender categories. Hollywood writes: “Christ’s body is an impenetrable rock and a body full of holes—and both at the same time … [displacing] any simplistic gender and sexual referentiality, for Christ’s body is both masculine and penetrable, both rock and feminized.62

That said, non-men, constantly made aware of their physical penetrability, disallowed from forgetting their bodies and bodily boundaries, have been producing empathic knowledge regarding the confrontation with the unknowable for centuries. Female mysticism offers a foundation for non-anthropocentric knowledge that is not at all opposed to other types of knowledge. This is fertile ground for contemporary fiction—as evidenced by VanderMeer, who manages to imagine himself, with radical empathy, into the experience of the female biologist. One role for the New Weird in today’s literary landscape may be to grow mystical knowledge, beyond the framework of religion—and also beyond the framework of institutionalized science.

Near the end of her account, the biologist says of the transformation of Area X: “I can no longer say with conviction that this is a bad thing. Not when looking at the pristine nature of Area X and then the world beyond, which we have altered so much” (156). She can no longer see her decreation, nor the decreation of the current human-centric world, as negative. It is, like the divine, beyond all positive and negative distinctions. “Area X is frightening, yes, but what appears to be happening there is not a reversion to Chaos and Old Night,” as Old Weird fiction would have it. Here, in the living, sporous world of New Weird fiction, may be “the start of a comprehensive reversal of the Anthropocene Age.”63 Loss of bounded self is only truly horrifying within an anthropocentric framework that prizes human being in its current state over all other forms and ways of being. Active self-annihilation might, paradoxically, offer a path toward ecosystemic preservation.

Reviewers and fans of the Southern Reach Trilogy have speculated that Boris and Arkady Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic (1972), which Andrei Tarkovsky adapted in the movie Stalker (1979), are also among the prime influences or precursors for Annihilation and Area X. Argubaly, this retroactively places the Strugatskys and Tarkovsky in a Weird lineage. For example, see →.

Jeff VanderMeer, Annihilation (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014). While more of an explanation of Area X, including its inception and its governance, gets laid out in the second and third books of the trilogy, in this essay I stick to the scope of Annihilation. The book’s success bridged VanderMeer’s work into mainstream fiction, and it was recently made into a movie by director Alex Garland.

Nick Statt, “How Annihilation changed Jeff VanderMeer’s weird novel into a new life form,” The Verge, February 28, 2018 →.

See Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Duke University Press, 2009).

William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (Modern Library, 1902), 414–15.

James writes that “personal religious experience has its root and centre in mystical states of consciousness,” yet mysticism is not religion. James, Varieties, 413.

James, Varieties, 418.

Bernard McGinn writes that in Christianity, “the core of mysticism” is “inner transformation.” This entails a “knowledge of God gained not by human rational effort but by the soul’s direct reception of a divine gift.” McGinn, Introduction to The Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism (Modern Library, 2006).

R. M. Bucke, Cosmic Consciousness: a study in the evolution of the human mind (Philadelphia: 1901), as quoted in James, Varieties, 435. Emphasis mine.

VanderMeer, 178

Ibid, 7

Ibid, 25

Marguerite Porete, The Mirror of Simple Souls, trans. Edmund Colledge, J. C. Marler, and Judith Grant (University of Notre Dame Press, 1999).

Anne Carson, Decreation (Knopf, 2005), 172.

Amy Hollywood, Introduction to the Cambridge Companion to Christian Mysticism (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 20.

Dionysius the Areopagite, The Mystical Theology and the Celestial Hierarchies, in McGinn (ed.), Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism, 286.

Meister Eckhart, The Essential Sermons, Commentaries, Treatises, and Defense, trans. Edmund Colledge and Bernard McGinn (Paulist Press, 1981). McGinn describes apophasis as “negative speaking in which all statements must be unsaid in deference to God’s hidden reality.” McGinn (ed.), Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism, 281.

Eugene Thacker, lecture, New School for Social Research, January 30, 2018.

Dionysius, Mystical Theology, 285.

VanderMeer, 37

Ibid, 41

Ibid, 65

Ibid, 89

Ibid, 133

Ibid, 28 The narrator in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris repeatedly describes a similar hope in the face of the alien other; it was easier to imagine he was going insane than that there was something occurring on the planet Solaris beyond his comprehension: “The thought that I had lost my mind calmed me down.” Lem, Solaris, trans. Bill Johnston (Pro Auctore Wojciech Zemek, 2011 (1961)), 49.

VanderMeer, 28

Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love, trans. Elizabeth Spearing, 1998. As quoted in McGinn (ed.), Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism, 242. An anchoress is a female anchorite, a hermit living in relative isolation.

Julian of Norwich in The Showings of Julian of Norwich, ed. Denise M. Baker (Norton, 2005), 126.

As described in Amy Hollywood, Acute Melancholia: Mysticism, History, and the Study of Religion (Columbia University Press, 2016), 172–74.

Eugene Thacker: “In the broadest sense, mysticism concerns the communication with or mediation of the divine; yet, with its emphasis on divine unity, mysticism also tends towards the breakdown of communication and the impossibility of mediation. Mysticism is also indelibly material, though it is often a materiality without object, in that the body of the mystical subject becomes the medium through which a range of affects—from stigmata to burning hearts—eventually consumes the body itself. Finally, while mystical texts do display a proliferation of bodies, affects and words—in effect ‘distributing’ the subject—in many texts there remains a dark, vacuous core that is not simply a node on the network or a topological enclosure.” Thacker, “Wayless Abyss: Mysticism, mediation and divine nothingness,” postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies 3, no. 1 (2012): 81.

Hollywood, Cambridge Companion, 25.

Hollywood, “Reading as Self-Annihilation,” in Acute Melancholia, 129.

Hollywood, Acute Melancholia, 182.

VanderMeer, 55

Ibid, 55

Ibid, 82

Ibid, 82

Hollywood, Cambridge Companion, 29.

Nancy Hartsock, “The feminist standpoint: Developing the ground for a specifically feminist historical materialism,” in Feminism and Methodology, ed. Sandra Harding (Indiana University Press, 1987), 167.

Hartsock, “Feminist standpoint,” 168.

Caroline Walker Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption (Zone, 1992), 241.

Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption, 254, 257. Bynum concludes that theologians in the Middle Ages were so certain that the material body was entirely necessary for personhood that the subsequent questions about corruptibility were much more important to them.

Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption, 255.

R. D. Laing, The Divided Self (Penguin, 1960), 68.

Laing, Divided Self, 41.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. Arthur Wills (University of Nebraska Press, 1997).

Paraphrased from a lecture by Eugene Thacker, New School for Social Research, January 30, 2018.

Weil, Gravity and Grace.

Chris Kraus, Aliens and Anorexia (Semiotext(e), 2000), 26.

James, Varieties, 455. Resistance to food is relatively common among female mystics, and is often interpreted as a willful negation of the gendered body, related to ideals of purity and virginity. In light of the way mystics describe their own experiences, these readings seem reductive.

“The mystical subject loses all distinction—including the distinction of subject and object, self and world—and yet it is somehow still able to comprehend this loss of distinction.” Thacker, “Wayless Abyss,” 83.

Kraus, Aliens and Anorexia, 27.

Kraus, Aliens and Anorexia, 48. Regarding the psychiatric patient, Laing wrote: “If we look at his actions as ‘signs’ of a ‘disease,’ we are already imposing our categories of thought on to the patient.” But “such data are all ways of not understanding him.” Laing, Divided Self, 33.

David Tompkins, “Weird Ecology: On the Southern Reach Trilogy,” Los Angeles Review of Books, September 30, 2014 →.

Wendy Chun, lecture, “The Proxy and its Politics” conference, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, June 24, 2017.

VanderMeer, 130. Tellingly, Chris Kraus describes experiencing grief as a sort of hyperobject, composed of “concentric rings of sadness. You close your eyes and travel outward through a vortex that draws you towards the saddest thing of all. And the saddest thing of all isn’t anything like sadness. It’s too big to see or name. Approaching it’s like seeing God. It makes you crazy. Because as you fall you start to feel yourself approaching someplace from which it will not be possible to retrace your steps back out.” Kraus, Aliens and Anorexia, 105.

Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 594.

Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 590. For her part, the biologist has no illusions about her knowledge being anything but situated, her sight anything but bodily. “I knew from experience how hopeless this pursuit, this attempt to weed out bias, was. Nothing that lived and breathed was truly objective—even in a vacuum, even if all that possessed the brain was a self-immolating desire for the truth.”[footnote VanderMeer, 8

Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 592. “Objectivity cannot be about fixed vision when what counts as an object is precisely what world history turns out to be about.” Ibid., 588.

Kraus, Aliens and Anorexia, 114.

Leslie Allison, “The Ecstasy and the Empathy,” BLOCK (forthcoming 2018). VanderMeer said in an interview: “I think any time you see more connection, whether you see connections on the human level or just in general about what we call the natural world, there’s more of a chance for empathy, and understanding and inhabiting a different point of view. And I think that’s what we really need. Beyond just like, you know, converting to solar.” Timothy Small, “The Strangling Fruit,” The Towner, July 10 2016 →.

Hollywood, Acute Melancholia, 187.

Tompkins, “Weird Ecology.”

Category

Subject

Thanks to Eugene Thacker and Simon Critchley for their course on mysticism at the New School for Social Research in Spring 2018. Thanks also to Jess Loudis for the essay title.