1.

For forty years my feminist project has involved creating concepts with which to think about the challenges posed by the encounter of feminism with art, and art with feminism.

This was not an encounter that was to be anticipated. In the 1970s, art did not expect feminism. At the very same time, the emerging Women’s Liberation Movement, as we knew ourselves at that moment of intense social and political activism, did not place art high on its list of priorities. At best artists might be useful for making posters and other agit-prop materials. At worst, art was a bourgeois distraction irrelevant to the struggles in which women were involved for equal pay, personal safety, sexual self-determination, and control over their own fertility and bodies in conditions of neocolonial and intensifying class conflict and aggravated racism.

If we look further back we can also see that historical feminism did not, either in its late eighteenth-century philosophical formulation or in its nineteenth-century political eruption and militancy, engage with the visual arts per se before the 1970s. It is true, as art historian Lisa Tickner has indeed shown, that by using the retrospect from later twentieth-century theories of performance and the politics of representation we can see how brilliantly and purposively early twentieth-century suffrage movements utilized many aesthetic strategies of political self-fashioning and costuming, image-making, and public procession with banners to assert the political voices of women in public space. But apart from a few named artists like Sylvia Pankhurst, there was not a corresponding artistic dimension to those campaigns.1 It is indeed possible, as argued by feminist theorist Ewa Ziarek, to reclaim the aesthetic radicalism of women writers and artists of the 1920s and ‘30s as a parallel to the deeper radicalism within political thinking amongst the militant suffrage theorists.2

The shock of the encounter after the mid-1960s between art, itself being transformed by the Conceptual project, and feminism, being transformed by its own theoretical revolution, has been mutual and creative. Yet has it been understood? Are we not still confined instead to conventional art historical categories and methods? For instance, how often is “feminist” used as an adjective to describe a style, an iconography, an authorial intention, missing the transformation demanded of such art-historical concepts by the force of feminism as intervention and effect?

Thus I return to my opening statement about why we need to invent concepts to confront what has happened in this encounter between art and feminism, and to understand what is happening in their relationship now. Australian philosopher Elizabeth Grosz explains the relation of concepts to the future of feminist theory and its potential to help change the afflicted world we inhabit:

We need concepts in order to think our way in a world of forces we do not control. Concepts are not a means of control, but forms of address that carve out for us a space and time in which we may become capable of responding to the indeterminate particularity of events. Concepts are thus a way of addressing the future, and in this sense are the conditions under which a future different from the present—the very goal of every radical politics—becomes possible. Concepts are not premonitions, ways of predicting what will be; on the contrary, they are modes of enactment of new forces; they are themselves the making of the new.3

Grosz then turns to explain theory as virtual:

In short, theory is never about us, about who we are. It affirms only what we can become, extracted as it is from the events that move us beyond ourselves. If theory is conceptual in this Deleuzian sense, it is freed from representation—from representing the silent minorities that ideology inhibited (subjects), and from representing the real through the truth which it affirms (objects)—and it is opened up to the virtual, to the future that does not yet exist. Feminist theory is essential, not as a plan or an anticipation of action to come, but as the addition of ideality or incorporeality to the horrifying materiality of the present as patriarchal, racist, ethnocentric, a ballast to enable the present to be transformed. 4

My most recent concept for thinking about feminist interventions into the study of artistic practice is called The Virtual Feminist Museum. The virtuality is not cybernetic but philosophical. Virtuality is a quality of feminism as a project because feminism is neither the past nor in the past. It is a project for a future still to come. The capacity of feminism to transform us and our world is as yet unrealized, even after almost two hundred years of effective social and political struggle, and half a century of intellectual work in both theory and creative activity. The Virtual Feminist Museum allows me to curate feminist installations that no museum would commission and that no corporate funder will support. I follow logics of connection and paths of association that are distinct from, if not deeply opposed to, those canonized by art history. These canonical logics are still apparent in contemporary art curation: the cult of the individual artist or the themed, hence essentially iconographic, exhibition. One key focus of the Virtual Feminist Museum concerns the ethics and body politics of one specific “pathos formula”: lying down. Pathosformel is the German term used by art historian Aby Warburg in his radical opposition to what he dismissed as aeshetheticizing art history—a bourgeois way of telling the story of art that pacifies the violence encoded in cultural forms, notably the image. Yet, Warburg is not the foundation for iconography. For Warburg, images are dynamic modes of the transmission of affects. Hence they are formulae for intensity, suffering, abjection, ecstasy, and transformation.

I am going to place a series of works in conversation because they share a certain formulation of the body as an articulation of both singular affective states and collective political conditions. The artists in question were both born in India. Their work speaks from its complex situation (in existential terms) to the world. I have focused on these artists because, within conventional art history, the thematic of the body remains “thought” in terms of a white, European body, with the classic opposition in the Western art tradition between the white feminine body as site of erotic lying down (the reclining Venus created by Girogione and Titian) and the black de-eroticized body of servitude. Whose body then is “the body” when we use such a concept? Is it not already performing an implicit, still-colonial racism?

My first image is a photographic work related to a long-term performance project entitled Lying Down by the Delhi-based artist Sonia Khurana (b. 1968). One of the earliest manifestations of this long-term work was itself entitled Logic of Birds, a performance enacted and filmed in a public space in Barcelona in 2006. Sonia Khurana has stated:

[To begin with] Logic of Birds was a direct consequence of the recent spate of incidents in my life, leading among other things to a sense of profound loss. This got translated into a query about the psychological implications of loss. The impulse to lie on the ground and feel the cold asphalt recurred several times, for different reasons. I was then in other cities and other things flowed into my consciousness … I was shooting, making images. I felt the deep desire to lie down like that, in Place de la Bastille, and then later in other places, as I travelled. I suppose this was a way of playing out a certain state of dereliction inherent within us.5

I interpret the Logic of the Birds as a new pathos formula: I am reclaiming for feminist analysis Aby Warburg’s brilliant and necessary formulation of the way the body becomes both a signifying gesture—an action—loaded with affect, and then an image that transmits a memory trace of once-experienced intensity. We might ask if Khurana’s lying down is the pathos formula of the psychologically and also the politically abject?

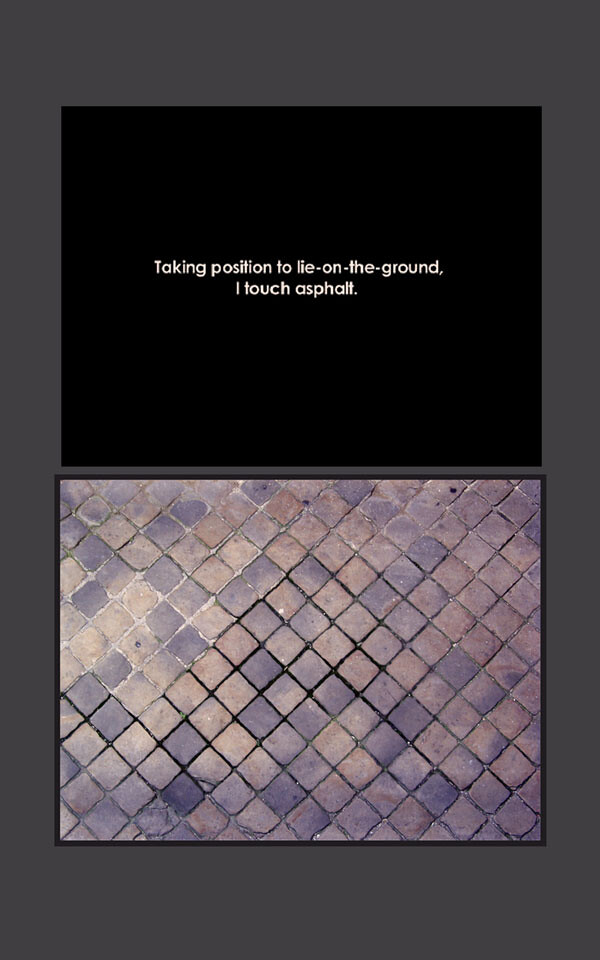

Sonia Khurana, Notes from a diary, Laad Bazaar, Char Minar, Hyderabad, 2010: an incomplete document of an aborted attempt towards a performative gesture, 2010. Diptych, digital prints.

Any interpretation must be sensitive to changing contexts, taking into account Khurana’s outsiderness in terms of her Indian nationality when she performs as a brown body on the ground in a European city such as Barcelona. When she lies down in India, it is her class and her religion, or lack thereof, that become significant and even dangerous. For instance, she tells the story of a performance in Hyderabad, this time using only the plexiglass simulacrum of her prone body. The story reveals the potency of the image qua image in a specific cultural context to generate a riot:

Hyderabad, 2010

… As I moved between places, over time, I had started to place a simple cutout of my prone form in Plexiglas. It photographed well, and its reflective surface acted as a kind of mirror for action that surrounds it.

Near Laad Bazaar in Char Minar, I found a good spot surrounded by pigeons, in Charminar, just outside the square, a few yards away from the boundary of the Mosque.

No sooner had I placed the cutout on the ground to take a picture, a mob appeared. In a flash I was surrounded by very angry people, both men and women, young and very old. There is no rationale to mob fury, I know. But that such an innocuous action elicited mob fury, was incomprehensible to me. The spectacle that ensued seemed unreal and all to familiar at once: it dawned on me that here I was an intruder and the innocent object in my hand: a plexiglass cutout of my prone form was seen as blasphemous, even though I was at considerable distance outside of the boundary of the [sacred] mosque.

From here on, taking pictures was out of the question, and I also immediately removed the plastic cutout. However, I really needed to be able to “speak” to the crowd, to ease the cultural gap. My reconciliatory note was totally lost amidst the hostile din: the crowd was hell-bent on living out its hysteria, irrespective of whether or not its cause merited violent reaction. Soon, a cop appeared on the scene and shooed me away, ostensibly towards safety in a police station, where further questioning and reprimand awaited me.

All this for taking a picture of a small plastic object whose edges are rounded, not sharp. Elsewhere, the very same gesture has either gone unnoticed, or has aroused mild curiosity, even discussion, amongst people on the street. But never a violent reaction.6

Khurana’s work registers unnamed personal loss that extends, by aesthetic formulation, to signify a shared condition. Lying down “speaks” the weight of the trauma of psychological dereliction in the pathos of that act of giving way, desiring the support of bare earth or hard ground, or giving into a wish to escape into unconsciousness or sleep that might also feel like death. Lying down takes the artist—and the viewer—to the borderline where subjectivity is under such pressure that it experiences itself as becoming abject. The abject is where we are neither subject nor object. As abject, the subject experiences its own undoing in the fading of its necessary boundaries that define the corporeal and sustain as distinct and whole the imaginary ego. The subject feels as if it is collapsing into de-subjectivized matter or unbounded bodiliness.

Sonia Khurana, Lying-down-on-the-ground, 2006-2012. Documentation of performative act, various locations. Top row: Place Bastille, Paris (2010); Bottom row: Republic Day after the parade, India Gate, Delhi (2009).

Sonia Khurana acknowledges the risk of becoming abject, resisting its claims through her beautiful, wonderful concept of seeking a “corporeal eloquence” created at this borderline. Lying down does not produce a collapse of meaning, but rather the possibility of a relay between this body-state and thought-in-language.

I would like to talk about some of my concerns with the performing of the abject, especially the power or the lure of the abject. I am immensely concerned with a corporeal understanding of the body. I find that corporeal significations are better resolved through performance. Through performance, I can engage with the constant struggle between body and language, to achieve a corporeal eloquence.7

With this phrase “corporeal eloquence,” Khurana draws our attention to something more social: “I could say that another underlying desire was to recuperate the lost or residual ‘body matters’ which lurk, unattended to, on the sidelines of the social.”8

The significance of the abject is that it represents the loss of any place from which to sustain the conditions of intersubjectivity. In Arendtian terms, these are specifically the conditions of any kind of political subjectivity and, as such, political action. Feminism is, I suggest, to be understood as the creating, calling forth, or inciting of a new political subjectivity and hence space for action. Here is the first implicit indication of my bigger argument about feminism and the body, the body politic, the embodied political subject, and the public space of political realization.

This political dimension of subjectivity brings into view the agency of the artist in relation to the negotiation of power and powerlessness as a political position in the world and the art world. Khurana writes:

It has occurred to me, in retrospect, that the language in which I chose to express this new state of mind was, in fact, very much in tune with my ongoing interrogations of “self-appointed” positions of powerlessness, and how the dynamics of these are played out in our day-to-day existence. I believe that the act of divesting oneself of power is ultimately empowering. This can be profound as well as ironical.9

Khurana’s work is a form of research, via performance, into the ethics but also the politics of being:

With the “lying down …” project, I have been asking myself: Can the critical possibilities offered by small acts of transgression be considered beyond their value as individual acts, for the potential of their accumulation? And can the dynamic build-up of infinitely small disturbances change structure into movement, a thing into a current?10

Sonia Khurana, Lying-down-on-the-ground Poem, 2017. Installation view. Digital photographs and video still.

I now want to offer a close reading of a 2009 poem-text by Sonia Khurana that relates to Lying Down, with my analysis in italics below each passage. The poem-text Lying-down-on-the-ground forms part of an installation composed of a text-based video and images, two of which are illustrated here, juxtaposing phrases from the poem and a visual counterpart. The movement of her thought and the structure of her language and phrasing speak to both the processes of art and art’s action in public space, which is the space of encounter between the aesthetic and the political. We must listen for the enunciative position of the speaker/writer; this position is the position of an international artist, an Indian citizen, and a woman with a specific political and familial history, who speaks to international, postcolonial feminism in the embodied voice of the artist:

Taking position to lie-on-the-ground, I touch asphalt.

I strive to assume the ultimate gesture: of abandonment, dereliction, dissidence.

The poem is in the first person; as such it summons the second person: “I” calls for “you.” The poem addresses me. But it is she as an “I” who must feel along the length of her body what normally only our feet traverse. But this feeling of the earth—or rather, the modern industrial matter than covers the earth in cities—is reclaimed as art: the speaker strives for (but doesn’t necessarily achieve) a gesture that expresses giving up and feeling utterly alone, but that also expresses resistance in its embrace of vulnerability. As philosopher Judith Bulter has theorized (which I discuss further below), this vulnerability-as-resistance is a deeply political gesture in its refusal of conformity.

Thus, [self-consciously] I confirm lying down as my device for entering the spaces I encounter.

Thus, I try to assimilate these spaces and cities that I have never really belonged to.

The second register is space and its correlatives of belonging and outsiderness. Lying down on their asphalt, she places herself in intimate connection with cities in which she would seem to be a visitor; her act of lying down makes her more formally into a stranger, a foreigner, an outsider in these places.

Thus, I settle accounts with various proposals of art.

We have moved to an entirely different conversation. This phrase moves away from the immediate affective register of a loss of connection represented by the artist lying down, abandoned. Now the work seems to search for contact with the place to which she, the artist, is other but present. It is a site of trans-spatial conversation: it is art, it is about making art, it calls to be considered artmaking: artworking.

I formulate and reformulate the image of this body lying down.

I offer my virtual, vagrant, surrogate self for this sculptural operation.

Through ephemeral sculpture and temporary drawing I propose to find “art” between life and concept and object.

The language of art enables the evocation of the “sculptural operation,” the claiming of the living and lived-in body for formulation, for signification, for meaning. But her body is her own, a woman’s body, in the present, not an idealized, carved body. The lying-down body is later re-perceived through artistic reworking—through sculpture and drawing. It occupies the space between three terms: living bodies (“life”), conceptual work (“concept”), and an object now in the world to think through living and bodies (“object”).

Recognizing that “I” is already and always “us,”

I propose to place a singular self in the domain of a collective utterance.

The register changes again from art to the activation of the implied “you” who was at first a silent witness: come and lie down so we can share the space of existence. That space has been created by the individual “I,” solitary and derelict, who nonethless addresses a world of art and other bodies formulated by gestures, set in stone or other material.

You, who passes through this space, I invite you to come and lie down on the ground with me. If only for a brief moment.

I propose that through the act of lying down on the ground, we would share a space of existence, if only momentarily, to perform an inconsequential act.

Using our bodies, “we” can come together in this space of action (Arendtian for sure). In this gesture we collectively touch not just the ground or the earth, but the space of coexistence.

I propose that, in fact, this is an allegorical act.

The action has taken flight. The simple act of lying down now ascends to meanings that are experienced rather than captured by mere words. Allegory is the ruin of meaning, but also the hope of contact.

I propose chance encounters with you: the Public is my matrix for performance.

I propose to oppose the degree of separation: of public and private.

Accepting the risk of your refusal, I propose to explore an aesthetics based on failure.

Encounters based on an open invitation involve the possibility of refusal as much as the possibility of revolutionary engagement. But when members of “the Public” accept the invitation, they do not become mere tools of participatory art, workhorses of relational aesthetics. Khurana does not push the burden of being the artwork onto random individuals. Rather, she solicits a shared psychosocial experiment in which walking, vertical bodies stop and enter the horizontal dimension; here, lying down is abnormal, unusual, daring, weird, shameful, and above all vulnerable. Her invitation, were it to be ignored or refused, would leave her unbearably isolated. But if the invitation was accepted, the novelty of the resulting mass act would reclaim public space, not merely for her singular act of lying down, giving up, and being alone, but for a Rabelaisian inversion of the order of things. It could release an unexpected joy.

I propose to provoke a transgression through this absurd act.

A transgression that brings about a sudden, profound loss of self.

Transgression means crossing boundaries, whether moral or political. The former involves judgement, while the latter involves change. The experience of collective transgression brings into momentary being a collective, one that entails not a fascist yielding of the self to another, but rather a fluidity across normal boundaries: trans-gression.

No grand revolution, but potential catalyst for nascent political thought.

Bit by bit, I try to convert this gesture of lying-down-on-the-ground

from metaphor into “pure” act.

I propose not a theory of lying-down-on-the-ground, but a consciousness.[footnote Unpublished manuscript shared with the author.

Khurana’s Lying Down anticipated some of the political debates that have been fostered by Judith Butler, who has written on elective vulnerability as a necessary political act when we try to resist in and reclaim the political right to public space, even at the risk of violence. In 2016 Butler argued that we do not come into the public as a seditious mob, but as a fragile political community in the process of forming ourselves as a new community through our individual actions.11 For Butler, this necessarily involves risk. It creates a vulnerability that becomes the only language of resistance that we now have.

Butler’s political thesis clearly draws, however, on the analytical-aesthetic art and theory of the artist Bracha Ettinger (b. 1948), who formulated the connection between fragilization and resistance in 2009.12 At that time Butler was studying and writing about Ettinger’s art and theory. While Butler theorizes at the political level, Ettinger proposes that the way fragility works relates to our ethical capacity for trans-subjectivity, which, she argues, is the psychological precondition for the emergence of the political subject and the chosen political act. For Ettinger, self-fragilization is a proto-ethical gesture. It starts at the level of the aesthetic, and is pre-ethical and pre-political. The aesthetic process, in Ettinger’s writing and practice, prepares us for an ethical relationship (intersubjectivity and response-ability) that will lead to political subjectivity and action. It is what sensitizes us for both an ethical and a political relation, not to the other but to one another; the phrasing itself is a crucial reconfiguration of the phallic model of self/other.

In the Virtual Feminist Museum, Khurana’s gesture of lying down meets the artworking of Sutapa Biswas (b. 1962), who entered the art world twenty years earlier. Born in Shantiniketan, West Bengal, India, Biswas was raised and studied in Britain, where she now lives. Her student days coincided with the emergence of the Black Art Movement of the 1980s, and especially the movement of black women, of which she was an integral agent with her powerful speaking-back to her British teachers through Housewives with Steak-Knives (1985) and a performance titled KALI (1984). The key exhibition of Biswas’s work was “The Thin Black Line,” curated by the artist Lubaina Himid in 1985. In 1987, Biswas visited India for the first time since early childhood. This trip inspired a series of works, one The Pied Piper of Hamlyn: Put Your Money Where Your Mouth, which is her take on the postcolonial situation, and then a multipart installation using photography entitled Synapse. In this multi-part installation, of which I am showing two images from two pairs of hand-printed black and white photographs, she transgressively, in terms of contemporary Indian mores, juxtaposed her own reclining nude body with the corporeal and erotic exuberance of the intertwined bodies she had just encountered in classical Hindu sculpture.

-copyWEB.jpg,1600)

-copyWEB.jpg,1200)

Left: Sutapa Biswas, Synapse II:1, 1987–1992. Hand-printed black and white photograph, diptych, 112cm x 132cm. Right: Sutapa Biswas, Synapse IV:1, 1987–1992. Hand-printed black and white photograph, 112cm x 132cm. Both works are from the artist’s Synapse series.

In the Virtual Feminist Museum, Khurana’s and Biswas’s artworking, grounded in Indian cultural histories and the radical political contexts of the present, might meet the Cuban-born American artist Ana Mendieta (1948–85), who also laid her body on the ground as a political invocation of a political exile’s lost home. They might also meet queer Mexican-American artist Laura Aguilar (1959–2018), who laid her queer Mexican body in the Mexican desert in forms that reach back into neolithic cultural formations, such as the three-thousand-year-old Sleeping Lady found in the Hypogeum of Ħal Saflieni, itself a formulation of symbolically created earth works representing the pregnant body of a woman at Silbury Hill in the UK.

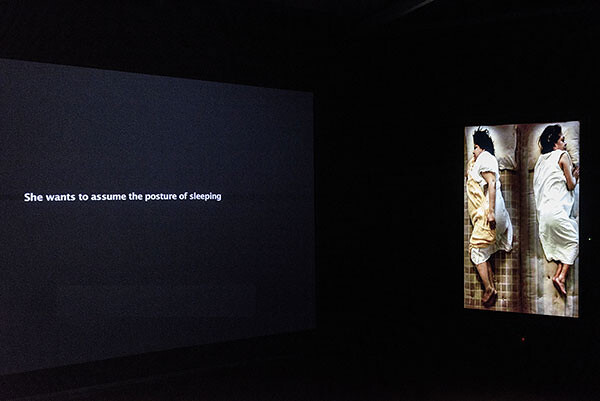

By invoking the trope of women and sleeping, we enter the realm of cultural narrative encoded in fairy tales. To the images, I would add the voice of French-Algerian Jewish writer Hélène Cixous, as she offers a feminist reading of the tale we call in English “Sleeping Beauty” (in German it is Dornrösen).13 “Sleeping Beauty” represents the imposed passivity of women in patriarchal culture that Sonia Khurana’s act transgresses as a feminist gesture to politicize and psychologize a specific woman’s body in public space as a form of silent yet eloquent speech. The final work in Khurana’s Lying Down cycle engages with sleep—sleep that does not come to the weary insomniac, sleep that steals time from the subject suffering a depressive condition. Sharing a bed with her mother while being filmed in relation to insomnia and somnolence, Khurana has made a film that works against the classic tropes of a woman in a bed asleep, because Khurana installs the moving-image work vertically. This large hanging image of still and moving bodies filmed in still-framed lapsed time is complemented by horizontal video pieces that form the installation “And the one does not stir without the other” (2014), comprising Sleep Wrestlers (2013) and Sleep Interlude (2008–13). It is from the latter that I quote from meditations on insomnia written over five years by the artist, spoken on the video by a trained actor and formally emerging and fading in a way that I cannot reproduce here except by formatting the words as short sequences of thought:

She wants to assume the posture of sleeping

in order that sleep might overcome the burden of consciousness

and conscience.

She wants this as the measure of her day,

both as an escape

and as a recollection of herself

She needs to divest herself of the demands of the day, until,

with daybreak,

she would have to put on the clothing of demand

and responsibility once again.14

In discussing Sonia Khurana and Sutapa Biswas, I have tried to offer a tiny introduction to two compelling artists not currently widely known in market terms, but who offer profoundly thoughtful feminist interventions enriched with geopolitical, postcolonial cultural resonance. Their work is well known in discerning artistic and curatorial circles. Their profound artistic practices preface my theoretical reflection on action in terms of feminist thought and practice. What I now want to do is explain the frame for reading the question of feminist theory and action with the work of these artists.

2.

My current work is also situated at the intersection of two areas of my recent research. One is the theme of “concentrationary memory”: this specifies the intersection of political theory and aesthetic resistance. The form of memory it represents is vigilant and anxious about the ever-present threat of fascism and the anti-political totalitarian disease that spread through the world in the twentieth century.

The second area is my research into the six installments of Documenta since that key year in world history, 1989. This research raises the question of the potential of this platform—the contemporary art exhibition or biennial, as epitomized by Documenta—to be a critical public space even while such exhibitions are also a central institution of the neoliberal globalizing financialization of the art world. Both of these are feminist concerns. Both are informed by a feminist engagement with the thought of Hannah Arendt, the political theorist of action and of what she named, in the English-language title of one of her most significant book, The Human Condition (1958).

The human condition is neither a nature nor an essence, but a political condition. We only came to grasp what this human condition is as a result of the totalitarian experiments to efface it. For those seeking total domination, it was the human condition that had to be destroyed in order to achieve total domination, because, according to Arendt, the human condition represents both the singularity of each person and the plurality of the many. It also signals our shared capacity for spontaneous—that is, new—action, for doing something new and unexpected is the essence of both revolution and the political as transformative action.

[Right:] Sonia Khurana, Sleep Wrestlers (2013) and [left:] Sonia Khurana, Sleep Interludes (2013). Installation ‘and the one does not stir without the other’ in Oneiric House, Delhi, 2013.

As an art historian I have wanted to know and to make visible what artists who are women have done and are doing. I focus on “artist-women” (a term I want to generalize in order to banish from our vocabulary horrors such as “female artist” and “woman artist”) who think and engage creatively with the world. This leads me to thinking about worldly women. The phrase “Women of the World” refers to the initiating slogan of the worldwide women’s movement circa 1970: “Women of the World Unite!” This was on a banner carried by women marching down Fifth Avenue in New York on August 26, 1970 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of women getting the vote in the US. This is not the origin of the world feminist movement. It is an image of movement, of bodies walking in public space, animating public space in celebration of a political event that was monumental for the history of these women locally and in celebration of a new and urgent feminist impulse to take action. We can trace this pathos formula of women walking in and occupying public space in their own name as political agents across the world—for instance, to the women’s marches of 2017, and to Delhi in 2012 following the hideous rape of one of thousands of women raped and killed for being in public in the streets of that city: women moving as a collectivity in diversity, with bodies holding words speaking to the world. These protests in India arose because even minimal access to public space is menaced for women, policed by sexual violence and murder. This, rather than the fact that there are Indian people lying down in the streets of India’s city’s, brings me back to Sonia Khurana’s Lying Down project: it took place in many public sites, each of which held specific political histories. Barcelona and Paris are political cities where public space has a political history. India’s public spaces have their own ethnic and religious dimensions, as Khurana found in Hyderabad. But the fragility and vulnerability of the bodies of women seeking to be part of the civic, political, and even economic life of the modern city is marked by the violence of the events against which the women in this image were protesting.

Sonia Khurana, Lying Down/Somnambulists, 2006. Digital print. Part of Insomnia diptych.

I am personally a product of one of the historical events I have named: the moment, circa 1970, of the repoliticization of gender associated with the many new social movements that emerged in the prior decade to contest the postwar settlement through decolonization, anti-racism, anti-sexism, and anti-homophobia. These social movements of abjected bodies and oppressed minds that had been denied speech recreated the space of the political as the space of appearance for new transnational communities—women subjects, colonial subjects, queer subjects, student and youth subjects, speaking and acting in the name of their plurality and their creativity. In the terms of political philosopher Jacques Rancière, these events represent the eruption of the “demos”—Greek for the “mass,” designating those without words, or those whose words had not been heard or granted acknowledgement as speech by the select and the elite that formed the circle of political citizens in ancient Greek city-states.

The new social movements as demos in revolt have demanded a place in political space, in the arena of enlarged and transformed democracy. Under these grand formulas such as “Women of the World Unite,” a new political entity made its appearance in the polis of speech and action, and movement: women emerged as political actors and formed themselves into a collective force overcoming all the traditional divisions between women in terms of class, race, sexuality, and ability, to identify a new virtual political commonality. In doing so, they did not forget and were never blind to the divisions between women in capitalist and colonial reality.

The declaration “Women of the World Unite,” as a speech act, as a performative call to unite, effectively made difference visible, opening up between women the hitherto-invisible space of otherness as a gendered issue within this newly invented and reimagined political unity: women. Feminist theory and practice emerges from this inevitable and necessary paradox. Only once you create, only once you summon into the political space, the political entity “women,” do the forms of difference between women become visible and demand their own urgent articulation and agonistic reconciliation. These differences are at once unique to each individual and shared with groups who experience and live the effects of their gender in relation to other, concurrent structures of oppression: race, class, geopolitical location, sexuality, physical ability, sexual safety, etc. The invocation of a new collectivity reveals the specific fault lines. It is crucial that we grasp this dynamic. Only when you summon women as women can you then make visible the differences between them as women. This means that this initial collectivity alone makes visible how class, race, sexuality, and other oppressions are always mediated by the omnipresent relations of gender. What is now fashionably named “intersectionality” both registers and occludes this dialectic, which is at the heart of feminism.

The demos speaks back to the polis. The politics of feminism is to change the constitution and passivity of the polis. My thinking about this issue rests on certain premises drawn from Hannah Arendt:

1. What is the polis? “The polis, properly speaking, is not the city-state in its physical location; it is the organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together, and its true space lies between living together for this purpose, no matter where they happen to be.”15

2. The polis is also the space of appearance “where I appear to others as others appear to me, where people exist not merely like other living or inanimate things, but to make their appearance explicitly.” Furthermore, “unlike the spaces which are the work of our hands, [the polis] does not survive the actuality of the movement which brought it into being, but disappears not only with the dispersal of people—as in the case of great catastrophes when the body politic of a people is destroyed—but with the disappearance or arrest of the activities themselves. Wherever people gather together, it is potentially there, but only potentially, not necessarily and not forever.”16

3. The polis is thus always a virtual space. It is where we generate power to act and to change. Like the space of appearance, power is always “a power potential and not an unchangeable, measurable and reliable entity like force or strength … [it] springs up between [people] when they act together and vanishes the moment they disperse.”17

The polis is thus not an institution but an event. This is why telling stories about what has been is so crucial. Narratives create a memory of such events, like feminism, or 1968, or 1989. But we can create a bad memory of the event, failing to keep its virtuality alive. Thus, how we narrate to each other the political moments of such gathering and political appearance and movement will determine its future power or its meaning.

I am arguing that current representations of feminism as waves and generations, as a battle between white and black feminisms, as a succession of good or bad moments, is politically destructive. What is now taken as normal, such as the idea of the second wave, is a limited story, and above all an American story, that ignores the many strong socialist currents of feminism across the world. I propose instead that we imagine feminism as a space, a landscape, variously populated by different settlements of speech and action, with many different routes of connection and even walls of agonistic division. It is a space of diversity and movement, not a single story of development or failure, or generational antagonism.

What the dominant narratives also miss is the agonistic creativity of democracy as a virtuality like feminism: a work in progress, and a process in which every advance against absolute oppression makes new lines of conflict visible, and brings forth new protests from hitherto speechless communities as well as creating new concepts and sites of action. I want to end with Hannah Arendt’s profound conclusion to an essay on the crisis in education, in her brilliant book on tradition, authority, history, freedom, and culture, Between Past and Present, published in 1968:

Education is the point at which we decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it and by the same token to save it from the ruin which, except for renewal, except for the coming of the new and young, would be inevitable. And education, too is where we decide whether we love our children enough not to expel them from our world, and leave them to their own devices, nor to strike from their hands their chance of undertaking something new, something unforeseen by us, but to prepare them in advance for the task of renewing our common world.18

Arendt suggests how we can understand ourselves as belonging to a common but changing world ever open to the new. Yet what is to come is also supported by what has been produced through earlier commitment to thought and creativity. Her vision rejects a linear succession of ideas or people. It proposes a co-inhabited world of communication, changing because of the inevitable difference initiated by the newcomers. The common world is dynamically changed all the time by emerging agonistic conflicts that can be creatively processed without the need to kill the past, or to denounce elders for their lack or failure to deliver a better present. We are working towards an unknown radical transformation of one of the most ancient and most persistent lines of violence between us in the plurality of the human community riven by lines of violent oppression we name class, gender, race. Feminism has just begun, in awkward and clumsy but also brilliant and creative ways, to challenge the horror of our world on one specific plane—gender/sexual difference—which incontestably intersects with many others, in a world now blighted by the raw violence of rampant and unregulated capitalism seemingly in possession of the entire globe, as well as threatened by annihilator ideologies.

Hannah Arendt’s model refuses the image of the family as the only site of transmission and chooses instead the freely engaged, multigenerational space of education: thought—which is constantly being renewed as much as it is being preserved and reinterpreted in critical discussion. We who work in education or in museums and galleries, which offer experience and knowledge to the public, are obliged to think deeply about the stories of the past and the present that we tell. We need to consider carefully the image of our common world that we pass on. From my feminist and postcolonial point of view, art has long suffered from bad, incomplete, and ideologically distorting narratives. The critique of its institutionalized forms was my primary concern as a feminist struggling with the institution of art history. But now feminism itself is at risk from bad stories, bad memories created within the feminist community. I think we are also deeply wounded by the thoughtless acceptance of deforming representations of feminism that are the product of unmanaged agonism. We need to focus on a profound political care for this very dangerous world we co-inhabit together. Feminism remains one of its most vital forces because, as the artists I have discussed show, we inhabit this common world in vulnerable bodies. Art speaks feminism aesthetically and feminist thought inspires artistic practice. I place both in the realm of speech, action, and transformation.

I have tried to show how gestures, images, and performances enable not only political thinking, but also political affect. Sometimes we need to lie down alone and silent in the street to register the weight of the world; other times we need to gather to fill the streets and speak back. Sometimes we place our bodies nakedly and vulnerably in the world of history or in landscapes of memory. In this article I have tried to show how aesthetic gestures, images, and performances make political thinking possible precisely because they work at the level of both thought and affect, and engender the space of appearance, which is the space of both speech and action.

Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907–14 (University of Chicago Press, 1988).

Ewa Ziarek, Feminist Aesthetics and the Politics of Modernism (Columbia University Press, 2012.)

Elizabeth Grosz, “The Future of Feminist Theory: Dreams for New Knowledges,” in Undutiful Daughters: New Directions in Feminist Thought and Practice, eds. Henriette Gunkel, Nigianni Chrysanthi, and Fanny Söderback (Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), 13–22, 16.

Grosz, “The Future of Feminist Theory,” 15.

Unpublished manuscript shared with the author.

Unpublished manuscript shared with the author.

Unpublished manuscript shared with the author.

Unpublished manuscript shared with the author.

Unpublished manuscript shared with the author.

Unpublished manuscript shared with the author.

Judith Butler and Zeynep Gambetti, Vulnerability in Resistance (Duke University Press, 2016).

Bracha Ettinger, “Fragilization and Resistance,” Studies in the Maternal 1, no. 2 (2009): 1–31.

Hélène Cixous, “Castration or Decapitation?” trans. Annette Kuhn, Signs 7, no. 1 (1981): 41–55.

Khurana

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, 1998), 198.

Arendt, Human Condition, 198–99.

Arendt, Human Condition, 200.

Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Present: Six Exercises in Political Thought (Viking Press, 1968), 193.

Category

Subject

A version of this text was delivered as a talk at Haus der Kunst, Munich, May 4, 2018, for Feminism and Art Theory Now, organized by Lara Demori. All images courtesy of the artists.