Two puzzles dominate recent discussions of Soviet literature and Marxist aesthetics in the 1930s. The first is how the official Soviet system tolerated and even at times celebrated such an idiosyncratic writer as Andrei Platonov, who in the last twenty-five years has emerged as the central literary artist of the time. The second puzzle is how socialist realism, a literature wholly focused on the future, came to model itself on nineteenth-century realism, with the result that the bulk of socialist realist novels (and works in other literary genres and artistic mediums) read like tedious exercises in nostalgia, while artists who really anticipate the future, like Platonov, became marginalized.

These two puzzles have brought close attention to the circle around the journal Literaturnyi kritik (Literary Critic), which had been created in 1934 as a locus for theorizing socialist realism, became closely allied with Mikhail Lifshits and other progressive Marxist philosophers, and also published the bulk of Platonov’s critical writings. In August 1936 Literaturnyi kritik broke with its charter to publish two stories by Andrei Platonov, “Immortality” and “Among Animals and Plants,” in the same issue that Georg Lukács published “Narrate or Describe?,” a foundational work in the theories of narrative and of realism. In this essay I propose to read Platonov’s “Immortality” together with Lukács’s “Narrate or Describe?” and Lukács’s review of “Immortality,” as part of a wide-ranging dialogue that also involved Viktor Shklovsky, about realism in general and the method of socialist realism in particular. This dialogue suggests that, far from legislating an outmoded style for the novel, Lukács derives from Platonov’s fiction a portable model of socialist realist method that will ensure the dual agency of the artist—as composer and medium of history—while allowing literary form to adapt to continual changes in the structure of history. Recovering the ambition of Lukács’s essay not only clarifies its historical context, but also suggests how the realism in question then might be the realism with which we still contend in our own day.1

1. “Immortality” and Socialist Realism

“Immortality” was commissioned from Platonov under the auspices of a large project called “People of the Railway Empire,” initiated by the Union of Soviet Writers and the railway newspaper Gudok (Horn) in late 1935. In line with the new Stakhanovite movement, which showcased particularly productive individual workers in each major industry, on July 30, 1935 Stalin gathered the most illustrious railway workers for an awards ceremony at the Kremlin. By August 17, working at a Stakhanovite pace, the publishing arm of the rail industry prepared and published a commemorative volume, Liudi velikoi chesti (People of Great Honor), which featured brief biographies of the sixty-seven award-winning railway workers. Sometime that autumn a decision was made to commission literary works about them. Platonov was assigned two Stakhanovites of the rails: pointsman Ivan Alekseevich Fyodorov of Medvezh’ia gora station, and stationmaster Emmanuil Grigor’evich Tseitlin of Krasnyi (Red) Liman station. Fyodorov became the protagonist of “Among Animals and Plants,” in which he is maimed while trying to stop a runaway train, is honored at a ceremony in Moscow, and promoted to the position of coupler. Tseitlin was fictionalized in “Immortality” as Emmanuil Semyonovich Levin, the indefatigably caring chief of Red Peregon station.

Platonov (1899–1951) was a natural choice for the project. Born in the family of a railway engineer, he had frequently set his stories in and around rail yards. He explained his railway obsession in a text later published by his widow Mariia:

Before the revolution I was a boy, but after it happened there was no time to be young, no time to grow; I immediately had to put on a frown and start fighting [i.e., in the Civil War] … Without finishing technical college I was hurriedly put on a locomotive to help the engineer. For me the saying that the revolution was the locomotive of history turned into a strange and good feeling: recalling it, I worked assiduously on the locomotive … Later the words about the revolution as a locomotive turned the locomotive for me into a sense [oshchushchenie] of the revolution.2

A revolutionary fact gives rise to a feeling and organizes labor, but then returns to a metaphor that rapidly accelerates out of control. This literal belief in metaphor animated socialist realism, the official aesthetic system of the Soviet Union beginning in 1932, and Stalin relied heavily upon the mobilizing power of metaphor when, in 1935, he placed the rail industry at the center of public discourse, as seen in railway commissar Lazar Kaganovich’s speech at the celebration of July 30, 1935:

In The Class Struggle in France Marx wrote that “revolutions are the locomotives of history.” On Marx’s timetable Lenin and Stalin have set the locomotive of history onto its track and led it forward. The enemies of revolution prophesied crashes for our locomotive, trying to frighten us with the difficulty of its path, its steep inclines and hard hills. But we have managed to lead the locomotive of history through all inclines and hills, through all turns and bends, because we have had great train engineers, capable of driving the locomotive of history. We have conquered because our locomotive has been steered by the dual brigade of the great Lenin and Stalin.3

Tropes unexpectedly spawn real imperatives. Though Platonov had been marginalized since his stories attracted Stalin’s personal ire in 1929 and 1931, the railway commission promised a way back into print.

“Among Animals and Plants” was accepted by the journals Oktiabr’ (October) and Novyi mir (The New World), but Platonov refused to make the changes they demanded. Both “Among Animals and Plants” and “Immortality” were then rejected by the prestigious almanac God Deviatnadtsatyi (The Nineteenth Year), before being accepted by the journal Kolkhoznye rebiata (Kolkhoz Kids), where they appeared in abbreviated adaptation for children.4 The decision by the editors of Literaturnyi kritik to publish Platonov’s stories as the first and last ever works of fiction ever included in the journal demonstrates both their high regard for Platonov and their determination, despite his difficulty in finding outlets for his work, to see him in print.

Given the political tenor of the moment—August 1936 also witnessed the first Moscow show trial of Stalin’s rivals—it was an act of no little boldness. In an extended but unsigned preface, the editors explained their decision as dictated by the timidity of literary journals’ editorial boards, which prefer safe “routine” and “cliché” to a realism that reveals contradictions and incites reflection:

We categorically reject the formula “talented, but politically false.” A truly talented work reflects reality with maximum objectivity, and an objective reflection of reality cannot be hostile to the working class and its cause. In Soviet conditions a work that is false in its ideas cannot be genuinely talented.5

What sounds like pure casuistry reflects the journal’s consistent position that literary narrative possesses a degree of autonomy, i.e., means of efficacy that cannot be mapped directly onto ideology: “Vigilance is necessary. In order that it be real, actual, Bolshevik vigilance, however, and not just a bureaucrat’s fear of ‘unpleasantness,’ it is necessary first of all to know literature.”6

Georg Lukács was a leading light of the journal, and the unnamed editors’ opposition between “literature” and “bureaucracy” calls to mind Lukács’s 1939 essay “Tribune or Bureaucrat?” In fact the entire project “People of the Railway Empire” had been conceived along roughly Lukácsian lines, considering his opposition to pure factography in the 1932 essay “Reportage or Portrayal?” The project was to be rooted in close study of Soviet life, specifically through an archive of transcripts of worker interviews that were commissioned especially for the occasion. As its organizer Vladimir Ermilov stressed, writers would travel to the home locations of their subjects “for personal impressions, so that this figure really comes to life in the hands of this writer when he is writing, working.”7 The result will be that “this literary work will not be isolated from the specific nature of the railway … in order that these works show people in the genuine, specific surroundings in which they live, work and fight.”8 Unlike previous collective documentary projects (e.g., on the heroic Cheliuskin expedition to the Arctic Sea or on the construction of the Moscow Metro), authors were urged “to provide stories, highly artistic documentary sketches and literary portraits, written by authors themselves over their personal signature; not reworked transcripts but genuine, self-sufficient artistic works about the person.”9 In addition to prose works written on the basis of the transcripts, Ermilov encouraged the creation of plays and also a “railway Chapaev,” modeled on the popular 1934 sound film about a Civil War-era commander.10

Platonov fulfilled his commission with admirable conscientiousness, completing his two stories by the deadline of February 10, 1936. For “Immortality,” in addition to renaming his protagonist and the location, Platonov appears to have used the (unknown and possibly lost) transcript of Tseitlin’s interview with great license, deriving from it only the basic picture of a railway station chief working tirelessly to keep trains on schedule despite the incompetence and truculence of less conscientious coworkers. In Platonov’s story the logistics specialist Polutorny is preoccupied with finding a Plymouth Rock cockerel for his hens. Another logistics specialist, Zakharchenko, spends most of his time at his pottery wheel producing wares that he sells at great personal profit. Night supervisor Pirogov is depressed, needy, and incompetent, while Levin’s assistant, Yedvak (based on the word for “hardly,” yedva), is simply lazy. Protected only by his loyal but limited cook Galya, Levin sacrifices sleep and nourishment to keep a watchful eye over the entire operation.

In his story Platonov observes a delicate oscillation between documentary source and fictional invention. Traveling to Krasnyi Liman only after finishing the story, Platonov found Tseitlin “intelligent (true, I’ve only spoken to him for ten minutes so far) and very similar to his image in my story.”11 Publishing the story in Literaturnyi kritik, Platonov attached an enigmatic note: “In this story there are no facts that fail to correspond to reality at least in a small degree, and there are no facts copying reality.”12 Platonov strives for realism, but realism excludes the “copying” of reality. So what, for Platonov, was realism?

2. Realism as Articulation

It was a version of this question, I will argue, that stimulated Georg Lukács to publish “Narrate or Describe?,” one of his major statements on the theory of narrative, in the same issue of Literaturnyi kritik as Platonov’s “Immortality.” Lukács begins (“in medias res,” he admits) with the coincidence of two parallel scenes in contemporaneous novels named for anagrammatic heroines; namely, the horse races in Emile Zola’s Nana (1880) and Lev Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1873–1878). Zola’s “brief monograph” about horse racing is a symbolic insert into his novel about the prostitute Nana, while Tolstoy makes Fru-Fru’s fatal fall into a turning point for multiple plotlines centered on the adulteress Anna. Zola’s horse race is exterior to the central story, while Tolstoy’s is fully integrated. “In Zola the race is described from the standpoint of an observer; in Tolstoy it is narrated from the standpoint of a participant,” Lukács concludes.13 The question for Lukács is: Which writer—and which method—treats the event more realistically?

When it appeared in the original German in the November and December 1936 issues of Internationale Literatur, the Moscow-based organ of the international Popular Front, Lukács’s essay “Narrate or Describe?” was presented itself as an intervention in the heated debate over realism that was instigated on January 28, 1936 with an editorial in the central Party newspaper Pravda. The anonymous author of “Muddle instead of Music” condemned the “formalist” tendencies of Dmitrii Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, i.e., its excessive interest in matters of pure form, leading the opera to be promptly yanked from the stage of the Bolshoi Theatre. More articles followed, broadening the initial critique to cover not only the overemphasis on form (“formalism”), but also the opposite overemphasis on raw sensory data (“naturalism”), both of which become watchwords for modernism. The articles targeted a range of artists in various media: Shostakovich’s ballet The Limpid Stream (with librettist Adrian Piotrovsky and choreographer Fedor Lopukhov), artist Vladimir Lebedev’s illustrated children’s books, Mikhail Bulgakov’s drama Molière, and the collected writings of poet and novelist Marietta Shaginian. Threatening administrative penalties (or worse) for offending artists and critics, the campaign against modernist excess was quickly extended to all mediums of art and instilled a deep and lasting chill on Soviet culture. It suggested an end to the notion of socialist realism as an autonomous method that could engender a variety of styles and modes for socialism, and its transformation into an obligatory and uniform style based on the replication of safe artistic conventions encoded in a restricted canon of authoritative exempla.14

In the process of updating his argument to suit the new struggle against formalism and naturalism, Lukács introduces a fundamentally new concept of realism based on the treatment of chance (Zufälligkeit). Lukács judges Nana and Anna Karenina by their starkly different treatments of chance in the horse race scene: Tolstoy’s horse race is an “exceptional” event (112/101, 125/111), but one that is so closely integrated with the novel’s major plotlines that Frou-Frou’s fall reads like a death sentence pronounced on Anna herself. Zola’s, by contrast, is self-contained and easily separable from the rest of the novel. For Lukács, Tolstoy exemplifies how truly realist artists “elevate chance to the inevitable [das Zufällige in die Notwendigkeit aufheben]” (112/102). Lacking this air of inevitability, Zola’s horse race is merely a naturalistic “hypertrophy of real detail,” as Zola himself describes his method (116/104). For Lukács, Tolstoy “provides quite another mode of artistic inevitability [künsterlische Notwendingkeit] than is possible with Zola’s exhaustive description” (112/102). Lukács concludes: “Narration establishes proportions [gliedert], description merely levels” (127/112).

The established English translation of this line obscures the concept I take to be central to Lukács’s new concept of realism: articulation. In the Hegelian tradition articulation (Gliederung in German, raschlenenie in Russian) does not merely establish proportions and arrange into hierarchical order, but also elevates chance to the status of necessity. True to its etymology in Latin and German (artus and Glied, meaning a joint, limb, or member), articulation reveals details to be the limbs or members of an organism. Lukács is most interested in how narrative articulates isolated occurrences as events in history, understood in a Marxist vein; he argues that narrative articulation “conforms to the laws of historical development and is determined by the action of social forces” (122/108). Thus the “artistic inevitability” of the narratively articulated event (Ereignis) coincides with historical necessity. Lukács even goes so far as to argue that history itself “objectively articulates” (gliedert) the fictional world and the characters that the realist artist depicts (122/108).

Lukács’s dual concept of “articulation”—history working through narrative, and narrative working to produce history—draws on Hegel’s use of Gliederung in the second part of the Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences. Dedicated to the philosophy of nature, this section traces how simple organisms—plants and animals—express their inner idea or subjectivity by articulating themselves into complex forms. Through articulation, “subjectivity … is developed as an objective organism, as an image [Gestalt]”: “This moment of negative definition grounds the transition to a genuine organism, in which the outer image harmonizes with the concept, so that these parts are essentially members, while subjectivity is the all-pervading unity of the whole.”15

Lukács’s was also aware of a famous passage in the Grundrisse, where Marx deploys Gliederung to denote the process by which economic production articulates inchoate social relations into hierarchical structures, which can retrospectively be read as a palimpsest of economic history. By analogy with evolutionary paleontology, Marx suggests that new forms of society retain structures inherited from more archaic ones: “Bourgeois society … allows insights into the structure and the relations of production of all the vanished social formations out of whose ruins and elements it built itself up.”16 Lukács follows Hegel and Marx in using “articulation” as a way to hold together the individual and world-historical vectors of causality. When applied to narrative art, this means that the artist freely articulates his or her subjective concept in image-forms (Gestalt) or narratives (Erzählung) that coincide with the objective forms (economic or evolutionary) of historical necessity.

It may seem odd, in this light, that Lukács proceeds to pass ethical judgment on Zola’s method, instead of treating it as the objective revelation of historical necessity speaking through Nana. Doesn’t the very coincidence of such similar contemporaneous novels signify anything about the paths of modernity, beyond Zola’s willful deviation from realism? However, Lukács thoroughly rejects the notion that every work of art bears some truth about history, by means of some “immanent dialectic within artistic forms” (119/106). Instead, Zola’s deviation from realism is grounded in the alienation of professionalized literature (reflecting the capitalist division of labor) and in the author’s loss of belief in the possibility of social change after 1848: “Without an ideology [Weltanschauung] a writer can neither narrate nor construct a comprehensive, well-organized, and multifaceted epic composition” (143/114).17 Articulation—as the key to epic narrative composition—is the hallmark not of art as such, but only of art that has been guided by a conscious striving to capture the totality within a sequence of seemingly chance events, i.e., of art that is intentionally and studiously realist.

Read retrospectively, Lukács’s insistence on the author’s conscious ideological stand may seem to be an apology for the Communist Party under Stalin and its coercive legislating of aesthetic style. From the time of the Russian revolution Lukács had consistently hewed to the Leninist line concerning the role of the Party as the proxy of proletarian consciousness, opposing those like Rosa Luxemburg, Aleksandr Bogdanov, or Lev Trotsky who imagined proletarian consciousness as arising spontaneously and dictating its own terms and forms. Already in a 1932 essay, Lukács called upon writers to jettison any notion of fellow travelers in art (what he calls “tendency”) in favor of full-blown “partisanship,” which he defines in the following way:

what the class-conscious section of the proletariat wants and does, from an understanding of the driving forces of the overall process, and as representative of the great world-historical interests of the working class, portraying this as a will and a deed that themselves arise dialectically from the same overall process and are indispensable moments of this objective process of reality.18

In short, the Party does much the same work as realist artists, “portraying” diverse desires and events as part of a single overall pattern, i.e., articulating them as history. To articulate means to be articulated as a (Party) member (Mitgleid). At issue in “Narrate or Describe?,” then, is the ability of literary form both to express and to produce class consciousness by articulating the world-historical significance of actually-existing material conditions.

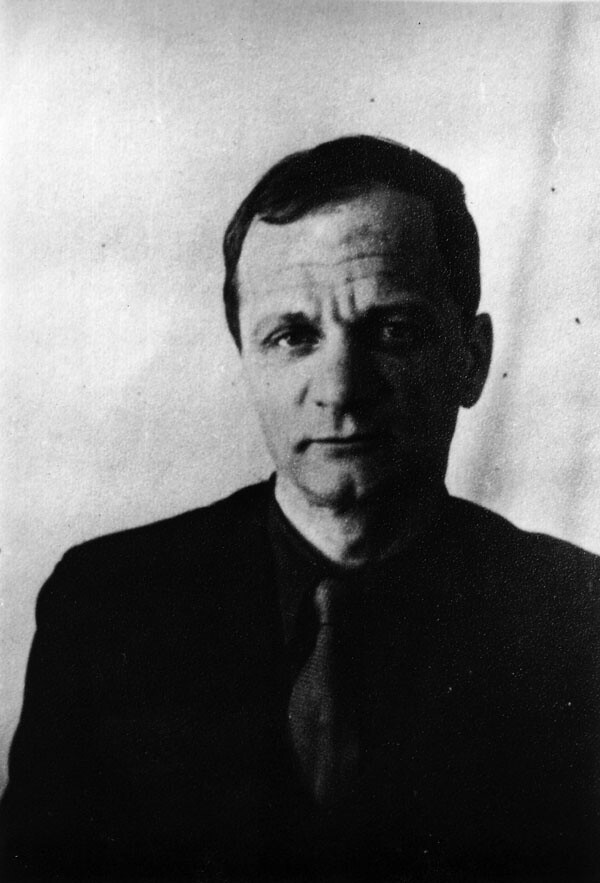

Andrei Platonov, c. 1938. Copyright: Mariia Andreevna Platonova/Wikimedia Commons.

3. Platonov and Lukács

The most conspicuous gap in “Narrate or Describe?” is the lack of any recent examples of realism, so that Lukács is forced to fall back on prerevolutionary models. For Lukács, recent bourgeois artists (both formalists and naturalists) have failed at realism in two conspicuous ways, both by trivializing reality and by deploying the wrong method for its artistic analysis. It is bad enough that modern artists “have diminished [verkleinlicht] capitalist reality, rendering its terror weaker and more trivial than it really is”; even more grave for Lukács that “the methods of observation and description diminish and distort the greatest revolutionary process of humanity.”19 Sinking even deeper than Zola into alienation, contemporary bourgeois writers suffer from two regrettable tendencies: objectivism and subjectivism. In spurious objectivism (i.e., naturalism), “the so-called action is only a thread on which still-lifes are disposed in a superficial, ineffective fortuitous sequence of isolated, static pictures” (144). The subjectivist (i.e., formalist) novel, typified by Proust, depicts a life so alienated from the world that it also turns into something “static and reified” (144). The case of James Joyce shows how extreme subjectivism ends up coinciding with extreme objectivism, producing a raw documentary record of merely subjective experience, leaving us with unanalyzed and unshaped surface data.

Soviet literature also presents a record of failure. In a final section on Soviet literature (included only in the German-language publication in Internationale Literatur, but omitted in the Russian-language publication earlier the same year), Lukács reports with indignation that novelist Iurii Olesha has expressed preference for Joyce over Gorky, which shows the lingering effect of the “late-bourgeois and Bogdanovite traditions” of conflating form with method. The choice between realism and its alternatives is ultimately “not literary in a technical sense”; it is, rather, ontological: “The new person cannot be formed out of this episodism [characteristic of both formalism and naturalism]. We must know and experience in a human way from where it is to come and how it is to undergo its growth.”20

In “Narrate or Describe?” Lukács gives little indication of how socialist realism might recover the power of realist articulation, creating the impression that the only path forward is to imitate the narrative techniques of the pre-1848 realist novel and of its later stalwarts Dickens and Tolstoy. Lukács’s cursory endorsement of Maxim Gorky—the undisputed hierarch of Soviet literature—seems merely a half-hearted acknowledgement of Gorky’s canonical position, especially in light of his recent death under suspicious circumstances in June 1936. The majority of Soviet novels, Lukács avers, foreground “neither human fates nor the relations among people, mediated by things,” but rather “the monograph of a kolkhoz, a factory, etc.”21 What is needed in socialist realism is “a view [Blick] on life that exceeds the description of its vast surface and the abstract arrangement of correctly observed social impressions; a view that sees the mutual dependence [Zusammenhang] of the two [i.e., of life and its arrangement] and brings this mutual dependence together poetically as a story [Fabel].”22 Lukács reports that the most significant Soviet writers are “striving for individual stories ever more energetically,” but as evidence he names only Aleksandr Fadeev, an author whose authority was more administrative than artistic (he took over as head of the Union of Soviet Writers after Gorky’s death).

But Lukács’s reticence regarding socialist realism should not surprise us given the opening words of his essay. “We begin in medias res” not only in the sense that the analysis of Tolstoy and Zola requires prior knowledge of the texts, but also in the sense that socialist realism is still in the process of being defined and created. Within a year Lukács broke his relative silence about contemporary Soviet literature with an article about the protagonist of Andrei Platonov’s “Immortality,” presented as a contribution to a special issue of Literaturnoe obozrenie (a supplement to Literaturnyi kritik where Platonov frequently published critical texts) dedicated to “Heroes of Soviet Literature.” Platonov’s meek station chief Emmanuil Levin makes surprising company for such canonical protagonists as Chapaev and Pavel Korchagin (from Nikolai Ostrovsky’s novel How the Steel Was Tempered). Lukács’s provocative canonization of Platonov’s story not only demonstrates his unconventional view of socialist realism, but also confirms his argument for realist representation as a crucial phase within the historical unfolding of socialism.

Based on the parameters laid out in “Narrate or Describe?,” Platonov’s story is a far from predictable exemplum for Lukács’s theory of realism. Not only is it a short story rather than the novels Lukács usually favors, but Lukács concedes that “Immortality” lacks suspense (Spannung) and even a “strong compositional backbone (sterzhen’).” However, the critic must avoid treating literary works “formalistically, according to outward characteristics,” Lukács argues, focusing instead on how Platonov’s story of the everyday remains free of “naturalistic greyness”:

Platonov’s main task is to reveal the tendencies of the development of people fighting for socialism within a picture of Soviet workdays [budni] … People who build this economy consciously, by overcoming all outward obstacles and inward difficulties, become socialist people in the process of their work and thanks to it.23

Drawing on his arguments in “Narrate or Describe?,” Lukács sees Levin as a “typical” character whose actions bring the elements of chance in socialist character-construction into a pattern of inevitability:

Negative traits in and of themselves are incapable of vivifying a literary image. The living interaction between a person’s virtues and mistakes; an understanding that these mistakes are no exterior contingency [sluchainost’], but very frequently emerge from those very virtues; an understanding that these positive traits, as a whole, are linked with a person’s social fate and with the main problems of modernity: this is the only possible basis for creating a living literary image.24

Quirky as Levin is, he is no sluchainost’, but instead emerges from Platonov’s story as neobkhodimost’—necessity:

It is typical that both here and in other similar cases [sluchai], in his low assessment of his own personality Levin constantly upbraids himself for what is actually his best quality—for his passionate immersion in work. This is no contingency [sluchainost’], no purely individual trait, and even less is it Levin’s simple eccentricity. This is a broad problem of the contemporary transitional period, a reflection of the social division of labor at the contemporary stage of the development of socialism—true, given in subjectivist distortion, but at the same time necessary [neobkhodimoe] in this very form.25

Platonov’s Levin is not a two-dimensional character illustrating a static ideal, not a “wind-up doll” (in Lukács’s phrase), but instead reveals the logic of his situation through conscious action, primarily labor: “Man is indeed, as dialectics teaches us, the product of his labor, in the broadest sense of the word.”26

Levin’s small-scale labor shows how the revolution is reversing the large-scale dynamics of chance in history, ridding the world of negative contingency. If the bourgeois novel showed the inevitability of accidents, then Platonov’s Levin asserts control over contingency, or at least its consequences: “Shunting still seemed to entail any number of minor accidents and unfortunate moments with people. But Levin knew very well that every little chance misfortune was, in essence, a big catastrophe—only it happened to have died in infancy.”27

It is therefore fitting that the story lacks suspenseful contingencies, relying instead on the drama of a protagonist existing on two scales at once, the personal and the world-historical: “On the small scale of this station he undertakes the program for the reorganization of the railway proposed by comrade L. M. Kaganovich.”28 The way in which small features of the portrait ramify into the larger productive processes are suggested by none other than Kaganovich, who calls Levin on the telephone in the middle of the night in order to make sure he is taking care of himself: “Listen, Emmanuil Semyonovich. If you cripple yourself at Red Peregon I will seek compensation as if you had ruined a thousand locomotives. I will check when you are sleeping, but don’t make a nanny out of me … ”29 For Lukács, the fulcrum of this drama is not a tragic knot, then, but a mechanical calculation of balance:

Platonov’s great artistry is evident in the way that the small, outwardly insignificant segment of life that he draws shows us an enormous multiplicity of processes that reveal this inner reconstruction of people. True, Platonov only charts the direction, the tendency of these processes, and—this is another strong side of his art—we do not see in his work any completely changed people, seeing only the “fulcrums of Archimedes” to which Levin applies his lever; we see the movement elicited by his stimulus and the wholly definite direction of this movement.30

Time might not be reversible, as Levin’s cook reminds him, but perspective is, and the drama of Platonov’s world is rooted in the constant oscillation of intimate and world-historical scales.

Though he does not use the term here, Lukács’s analysis of Platonov’s “Immortality” is clarified by the concept “articulation” from “Narrate or Describe?” Platonov’s Emmanuil Levin is more than a product of his outward conditions, in which he struggles against remnants of capitalism and for the introduction of socialist order. Within these conditions he struggles also to manifest himself as a new subjectivity, free of the consequences of the division of labor, which are still so patently visible in his coworkers. Therefore, Lukács comments:

His passion for technology and organization has never, not even for a second, given rise to the dry one-sidedness that is typical of managers of capitalist enterprises. For Levin the person and the machine, the person and technology, are inseparably linked to each other. The former controls the latter, and out of their fruitful interaction arises the socialist organization of the economy—and is born the new person.31

In contrast to the bourgeois-realist novel, where the protagonist is wholly conditioned by the external environment, ultimately by history, Platonov’s Levin defines himself as an independent agent in his work on the world and on other people. As Lukács remarks:

To expose “defects” in people’s personal lives and to “repair” these defects … exceeds the concrete tasks of organizing labor at the little station: they enable the growth of all of a person’s abilities, not just his “railway” ones, and help him to escape the petty, narrow, crippling frames of the rural or urban petty-bourgeois world.32

As for Hegel, then, the subject’s self-articulation renders its concept objectively, as history.

For Lukács, Levin’s “sadness” stems from his consciousness of the lag of material history behind his concept of it, which expresses itself in “impatience” and a “mental leaping ahead,” over the empty expanses of Soviet socialism in its anticipatory state, which separate him from his ultimate boss Lazar Kaganovich:

The distant, thick and kind voice fell silent for a time. Levin stood silent; he had long loved his Moscow interlocutor, but had never been able to express his feeling to him in any direct way: all means were tactless and indelicate …

“Here I have to think up people anew, Lazar’ Moiseevich … ”

“That’s the most difficult, most necessary thing [nuzhnoe],” said the distant, clear voice; one could hear the fine groaning hum of the electrical amplifier, reminding both interlocutors of the long space [dolgoe prostranstvo], of the wind, the frost and blizzards, of their common concern.33

The adjective “dolgii” is usually applied to time; the separation between the interlocutors—and the scales which they primarily inhabit—is both spatial and temporal. Overcoming the separation is not merely a goal to be attained in the future through labor in the present; it also requires an intimacy established through media, like the telephone, or like Platonov’s story. The task of literature is to animate the life-system with energy, bringing “organization” into harmony with “feeling.”34

Just as (in the words of Platonov’s narrator) “any system of work is just the play of a solitary mind unless it is heated by the energy of all workers’ hearts,” so also does life need to be humanized.35 “Oh, life, when will you get yourself organized so we don’t need ever to sense [chuiat’] you!” Levin sighs. By articulating and amplifying the tensions of the “transitional” moment, Lukács suggests, Platonov’s story works like the telephone that conveys Kaganovich’s concern to Levin, easing him into world-historical existence and bringing this perspective to bear upon small outbreaks of contingency. And yet the story constantly returns to the elusiveness of feeling in a world pervaded by concern for technology and other inhuman things:

But in the darkness of his mind, which was abundantly irrigated by blood, there glowed a single trembling point; it gleamed through the gloom of his eyes, half-closed by his eyelids, as if a lantern was burning at a distant guard post, on the entrance signal of the main route from reality, and this meek flame could turn at any instant into the broad glow of his entire consciousness and turn on his heart at full strength.36

The pilot light of consciousness flickers at the ready, protected from the chill winds of an obdurate world, watching for opportunities to articulate labor as history, as immortality. Literature not only awaits socialism, but also, for Lukács, socialist realism.

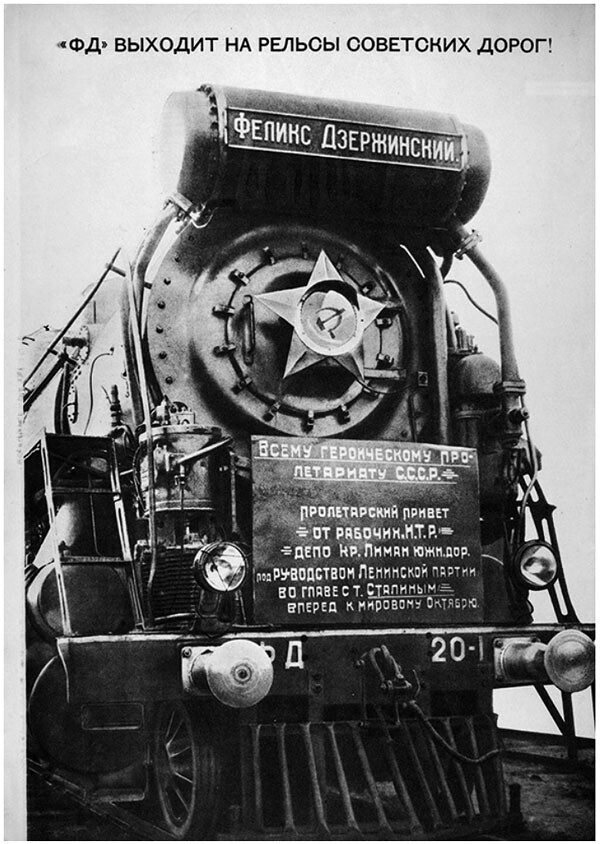

Page from the Soviet publication СССР на стройке (USSR in Construction).

4. Lukács and Shklovsky

The alliance between Platonov and Lukács, I am arguing, was a signal event in Soviet cultural life in 1936, but it can only be understood by considering also the role of Viktor Shklovsky, as instigator and gadfly. Shklovsky is best known for his youthful work on literary theory, but he remained prominent throughout the Soviet period as writer and screenwriter, literary and film critic, and theorist of socialist realism. Having been one of the proponents of radical factography in the late 1920s, Shklovsky’s niche continued to be the adaptation of documentary material in a constant stream of books and films, including the screenplay for the film Turksib (1930), about the construction of a rail line from Kazakhstan to Siberia, and an accompanying volume. After the dawn of socialist realism Shklovsky was closely involved in many of the most prominent documentary projects, beginning with the collectively researched and written volume The White Sea–Baltic Sea Canal in 1933–34 and Metro in 1935. At the beginning of 1936 Shklovsky became involved in the project “People of the Railway Empire,” for which Platonov was already at work on “Immortality” and “Among Animals and Plants.”

At organizational meetings at the Union of Soviet Writers on January 26–27, 1936—on the very eve of the anonymous article that condemned Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth and kicked off the anti-formalism campaign—a group of writers gathered to discuss “People of the Railway Empire” with professionals from the industry. True to the tenets of factography, Shklovsky strenuously disagreed with Vladimir Ermilov (one of the project’s initiators) on the need to impose narrative shape on the raw data of reality, which (in Shklovsky’s view) constantly outstrip the limits of our imagination: “Every day you read the newspapers and are surprised by what is happening there.”37 Shklovsky urged writers to take an example from champion locomotive driver Petr Krivonos, who consistently exceeded the speed and weight limits imposed by over-cautious bureaucrats. Against such “limitism,” Shklovsky argues that norms have to be derived from direct observation of practice, which is every day rewriting the very laws of nature.

What would it mean for a writer to be a Stakhanovite? Writer Isai Rakhtanov complained of the draconian submission deadlines—Shklovsky’s own contribution had been due already on January 10—but for Shklovsky “limitism” was just as pernicious in literary production as in rail transport.38 Most forcefully Shklovsky took issue with Ermilov’s insistence on writers’ authorship, even their signature, as the source of “genuine” literature. It used to be that physical labor was “nameless” and, as such, sharply contrasted to that of writers. Now that laborers are becoming heroes, Shklovsky argues, writers need to work out new ways of appropriating that labor without imposing their own names or, most importantly, their own voices, as Shklovsky explained in a speech at a gathering of Moscow writers in March 1936:

Take the people of “The Rail Empire.” People write well. People have learned to speak. People think well. The transcripts of their speeches … improve from year to year. It is not that the stenographers have learned to take better notes: it is that the people have changed. The voice of people has changed.39

Faced with the task of recording Stakhanovite voices, Soviet writers have succumbed to a new division of labor and, Shklovsky suggests, a new alienation: “People have divided their life into two parts … : work for themselves—of a purely literary type—and what they write about transport, the Metro, and the White Sea Canal.”40

Shklovsky’s argument for the preeminence of the laborer’s speech over the writer’s composition is clearly directed against Lukács, who had dismissed “factography” already in his 1932 essay “Reportage or Portrayal?” The concluding section of “Narrate or Describe?,” omitted in the Russian-language publication (as in later translations), renewed this polemic apropos of Sergei Tret’iakov’s notion of “the biography of a thing” as the epitome of the convergence between naturalism and formalism, which has resulted in a compositional monotony among novels, united by the same narrative conceits: “The naked theme can only show the socially necessary path without representing it as the result of endlessly crossing contingencies [Zufälligkeiten].”41 Caught at the center of all these contingent forces, for Lukács characters are reduced to bare schemata: “For people to receive true physiognomies and truly human contours, we must co-experience their actions.” The Soviet documentary novel, in Lukács’s view, is just as schematic as a naturalist one, only with the opposite sign: instead of novels ending with the inevitable crisis of capitalism, the Soviet novels end with the inevitable victory of the “hidden and suppressed correct principle.” “The authentic writerly work of discovery, of composition,” Lukács concludes, “should begin precisely at the point where the majority of our writers complete their work.”42

Shklovsky, by contrast, insists on the necessity not of articulating a person’s physiognomy as a historical forcefield, but rather of providing space for the person to articulate him- or herself. “The point is not to take a story and stuff it full of transportation,” Shklovsky added. “One must transfer the sense [oshchushchenie] of labor into the work.”43 In his theoretical writings and speeches Shklovsky tended to make these arguments performatively, i.e., through quotation, adduction of examples, and verbal play. This was the case also with Shklovsky’s own contribution to “People of the Railway Empire,” namely “Petr Krivonos,” a story-cum-documentary sketch published at the end of 1937 in the literary journal Znamia. Krivonos was the most illustrious of railway Stakhanovites and the main debunker of limitism in railway science, just as Shklovsky was in literary science.

Writing in his trademark telegraphic style, Shklovsky draws a consistent analogy between railway labor and literacy. Krivonos was raised in a poor family. His father Fyodor managed to build himself a house only through extreme parsimony. Having worked all his life, Fyodor knew the letters but never mastered the skill of combining them into words, leaving him in a world of acronyms:

He didn’t forget the letters because they walked alongside him on the rails, printed onto the locomotive: Ov, ChKZ, Shch [abbreviations of types of locomotives].

People at the station—those who were a bit more important [pokrupnee]—were also called not by names and syllables, but by letters. There were various kinds: TCh, DS, DSP [abbreviations of posts on the railway].

In the carpenter’s family the letters remained linked to railway people and locomotives, but not reading.

The carpenter taught his children literacy himself, showing them the letters.

The first letters which the carpenter’s son Petr learned were ChKZ [a four-axle locomotive from the Kolomensk factory].

The locomotive on which these letters shone was the most cozy; even a small child could climb onto it.44

Therefore, Shklovsky writes,

His father bought no toys, making them himself for his children, but only rarely. One time he made something like a model of a locomotive part.

It was interesting to watch the wheel spin on a wooden shaft. Petr called this toy “ChKZ.”45

Petr begins the art of combining language and the world when he begins to learn how to put trains together. Both skills are based on elementary montage, exercised on a scale model but transferable to full-scale mechanisms and processes.

As it expands, Petr’s literacy—and the consciousness it brings—remain inseparable from his labor on trains:

Finishing college, the pupil understands a locomotive just as one must understand a phrase in grammatical analysis.

This here is a noun, with a certain gender, number, and case. This, for example, is a piston shaft; it’s different on other locomotives, but here it is like this, playing the role of a connecting rod and serving to transfer movement from the piston to the crankshaft of the wheel; it turns straight movement into torque.

These words open up a conscious relation to the machine.46

With his mastery of grammatical and mechanical montage, Petr can begin to put together machine-based labor in hitherto unseen ways. Having determined his vocation, Krivonos enters an apprenticeship with Makar Ruban, who shares his “passion for locomotives.”47 Together they overcome the “wreckers” who hold to the “fascist” theory of the limit, and imprint their names on railway labor.

Shklovsky’s challenge is to find a verbal equivalent for Petr’s feats of labor. Instead of shaping his material as narrative, Shklovsky constructs the biographical narrative out of contingent, almost random fragments, including biographical details, local color, personal memories, instructions on the proper upkeep of locomotives, statistics, news of the day, and comments on the weather. All of this is arranged in an order that also seems random:

The days passed in a rising tempo.

The aircraft USSR-1b took off on June 27 at 5:25am. It landed safely, having reached an altitude of 16,000 meters and having performed 50 tests on cosmic rays.

70,654 train cars were loaded. The Donbass railway was among those over-fulfilling the plan. There was a competition for best conductor.

The glider pilot Kartashov took off, using a storm front. The storm cloud stretched for several hundred kilometers.

Using a powerful thermal stream, the glider pilot rose to 2,000 meters and, together with the storm cloud, flew in the direction of Serpukhov.

Man is adapted for success and happiness.

Man can do much more than he has up till now.48

As it happens, the transcript of Krivonos’s interview (with a writer named Kapustianskii) is the only such one known to have survived from the “People of the Railway Empire” project.49 It bears underlinings that coincide with passages quoted directly in Shklovsky’s biographical sketch, and which suggest how closely Shklovsky hewed to his source, in contrast to Platonov.

In a 1940 review of Shklovsky’s book On Mayakovsky (O Maiakovskom) Platonov defines Shklovsky’s signature “genre” by its “out-croppings” (otvetvleniia): “These outcroppings or tangential characteristics are so abundant that their tangle obscures the main trunk [kriazh] of the tree on which they grow.”50 But worst of all is that this “genre” becomes a “mechanism,” and the writer a “builder”: “Unless it is renewed, unless it is nurtured by living fate, writerly experience is the death of the artist … We have no need of mutually exchangeable details of the child’s toy ‘Meccano.’”51

The result of this mechanical style is that Shklovsky fails to capture the living subject:

He fails to understand that in identical circumstances people’s thoughts and actions will also be almost identical (and there is nothing bad or harmful in this), but their feelings always differ, their feelings are always individual and unique. Actions are stereotypical, but life is unrepeatable.52

For Platonov, Shklovsky’s style is suited for stamping identical copies of a single exemplum, but not for resolving the inner dilemmas of socialism experienced as life.

But Platonov misses the point. What is most striking in Shklovsky’s practice is not his style or his treatment of his subject, but rather his continual, full-blooded participation in the collective editorial process required by a project like “People of the Railway Empire.” In this Shklovsky appears the polar opposite of Platonov, who maintained a silent presence at the meetings, intent on getting his work published in a form as close as possible to his original composition. By contrast, Shklovsky’s socialist realism is a process that refuses to settle into a completed text, inhabiting instead a self-propagating (unfinalizable, one might say) cycle of commissioning, speech, recording, writing, discussion, reviewing, and new production. It gestures toward communism as a state not of history, but of language.

Shklovsky’s concept of socialist realism as a discursive process can be difficult to reconstruct based on the fragmentary transcripts and polemics that have come down to us. But in our case it does help to see how Platonov’s, Lukács’s, and Shklovsky’s writings can all be taken as links in a single chain of utterances about the conditions of realism under socialist construction.

The agit-train October Revolution included a car specifically outfitted for propaganda purposes. Photo: Vertov-Collection, Austrian Film Museum

5. Concluding Links

In his speech from March 15, 1936, responding to accusations of formalism, Shklovsky referred in his defense to his work on “People of the Railway Empire”: “I took pains to rouse Andrei Platonov for this work and am proud that he has written such a piece as ‘Red Liman’ [i.e., ‘Immortality’].”53 Shklovsky had reason to be proud, since it was he who first brought Platonov to broad public notice back in 1925 after he flew to Voronezh and interviewed Platonov for a documentary sketch with photographic illustrations, later adapted for inclusion in the book Third Factory (Tret’ia fabrika).54 Depicting Platonov as an eccentric irrigation engineer from the provinces suited Shklovsky’s idea of how industrial labor would produce its own distinct, truly proletarian intellectual culture.

Coming a full five months before the story’s publication, Shklovsky’s casual comment about Platonov’s “Immortality” also illustrates the kind of circulation that texts enjoyed in manuscript, especially via the writers’ unions and other organizations. It is possible that Lukács’s “Narrate or Describe?” also circulated in manuscript as part of the same broad discussion. In any event, comments by Shklovsky and others at a July 13, 1936 workshop called to critique Platonov’s other railway story, “Among Animals and Plants,” suggest familiarity with Lukács’s argument concerning realism in “Narrate or Describe?” before the essay was published. This is particularly true of critic Fyodor Levin, who in his critique of the story’s bleakness at the writers’ workshop seems to adopt Lukács’s terms as he complains about the lack of motivation in the events of the story:

The signals engineer has no joy in life. Joy occurs only because an accident occurred and someone performed a feat [podvig], moreover not a feat that he had prepared for, but simply a contingency [sluchainost’]. It might have worked out that the carriage that he was guilty of releasing had not been stopped, and then instead of an award he would have received a punishment. He let the carriage go and stopped it himself. This is an accident [sluchai] that could have ended in two ways … There is no hero, no feat, there is just a accident [sluchai] that allowed him to look with one eye into this other life, and then he again returned back; and the place he has returned to is a quite meaningless life.55

Platonov is defended by Semyon Gekht, who says: “An accident can also provoke a person, if there is something in his character.”56 He continues: “I am not against accident. Every narrative [rasskaz] has accident. The accident of Anna Karenina meeting Vronsky in the train. There as many such accidents in life and in an artwork as you like. But there is a pernicious kind of accident.”57

Not only does Gekht insist (like Fyodor Levin) on the terminology of “contingency” and “accident” when discussing Platonov’s railway story, but he also makes the connection to Anna Karenina. All of this confirms that Lukács’s essay “Narrate or Describe?” and Platonov’s two railway stories were understood to be links in a single extended discussion about realism in 1936.

If one assumes that Platonov and Lukács were in direct contact, one might even go so far as to read “Among Animals and Plants” as Platonov’s direct response to Lukács’s key notion of articulation. It tells of how provincial pointsman Ivan Fyodorov works his way up, first to the more central station of Medvezh’ia gora (Bear Mountain), and then earns himself a promotion to the position of сoupler (stsepshchik). Throughout the story Fyodorov is depicted as saddened by the profound alienation persisting between human and animal, human and machine, human and media. He desires renown, but achieves it only by causing an accident that maims his right arm. Fyodorov’s world-historical action, in short, comes at the cost of his own disfiguration, his own dismemberment (which in Russian is the same word as articulation, raschlenenie).

Again we are brought back to Anna Karenina, this time its finale, where the heroine also has a brutal encounter with a train. “Narrative establishes proportions,” the English translation reads. “Narrative articulates,” says Lukács in my reading. Given the ambiguity of the term Gliederung/raschlenenie, however, there is also a morbid possibility: “Narrative dismembers [gliedert/raschleniaet].”58 Is one supposed to think of Anna’s suicide at this moment in Lukács’s essay? Perhaps Lukács’s editor or censor did, which would explain why this sentence was struck from the Russian version of “Narrate or Describe?” published in Literaturnyi kritik in August 1936, against the backdrop of the first Moscow show trial.

But to articulate means also to clarify linkages, and in his essay Lukács supplements the principle of Gliederung with that of Verknüpfung—linkage. For instance, with the death of Fru-Fru, Lukács writes:

Tolstoy has made the coupling of this episode with the central life-drama as tight as possible. The race is, on the one hand, merely the occasion for the explosion of a conflict, but, on the other hand, through its coupling with Vronsky’s social ambition—an important factor in the subsequent tragedy—it is far more than a mere incident.59

Lukács is no doubt consciously echoing Tolstoy’s famous description of his practice in Anna Karenina, in a letter to Nikolai Strakhov from April 1876:

In everything, almost everything that I have written, I have been governed by the need to gather together thoughts coupled with each other, for expressing the self; but each thought expressed in words separately loses its meaning, is terribly denigrated, when it is removed from the coupling in which it is located. The coupling itself is composed not by thought (I think), but by something else, and it is impossible to express the basis of this coupling directly through words; you can do so only in mediation, by describing images, actions and situations in words.60

What is realist in the realist novel, then, is not its style or even its genre, but its operations of articulation and coupling, just like working on the railway.

How, Lukács asks, will the realist novel, this machine of articulation and linkage, be retooled for the aims of socialism now that history has made its ultimate turn? Lukács’s answer, I have been arguing, is that Andrei Platonov’s modest story “Immortality” provides the clearest indication of how his model of socialist realism will produce—indeed, is already producing—a literature for socialism, one that works by coordinating intimate and world-historical scales together without eliding the friction, even the violence, of their encounter.

Substantial links between Lukács and Platonov have long been suspected, but have never been examined in depth. In general terms Natal’ia Poltavtseva has proposed that “Platonov’s art was a metacommentary not only on socialist realism … but also on ‘the movement’ (of Lukács, Lifshits et al.)”; “Platonov i Lukach (iz istorii sovetskogo iskusstva 1930-x godov),” Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie 107 (2011): 253–70. While acknowledging that Lukács was “Platonov’s supporter in the 1930s,” Nariman Skakov has recently proposed to read Platonov’s novel Dzhan (translated as Soul) through Lukács’s early books Soul and Form (1912) and Theory of the Novel (1916); Nariman Skakov, “Introduction: Andrei Platonov, an Engineer of the Human Soul,” Slavic Review 73, no. 4 (Winter 2014): 722–24. Keen to preserve the notion of Platonov as an outcast, A. Mazaev has dismissed “Immortality” as an “opportunistic” story and diagnosed Lukács’s interest in it as a symptom of his “inability to distinguish genuine art from its counterfeit”; A. Mazaev, “O ‘Literaturnom kritike’ i ego estesticheskoi programme,” Stranitsy otechestvennoi kul’tury. 30-e gody (Gosudarstvennyi institut iskusstvoznaniia, 1995), 179, 181.

M. Platonova, “…Zhivia glavnoi zhizn’iu (A. Platonov v pis’makh k zhene, dokumentakh i ocherkakh),” Volga 9 (1975): 161. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the original for this text has never been identified or dated.

“Priem rabotnikov zheleznodorozhnogo transporta v Kremle,” Pravda, August 2, 1935, 1.

In issues 4 and 12 for 1936. A second version of “Among Animals and Plants” was printed under the title “Life in a Family” in the journal Industriia sotsializma (The Industry of Socialism) (no. 4, 1940). The story has been published in English in: Andrei Platonov, Soul, trans. Robert Chandler et al. (New York Review Books, 2008), 155–83.

Literaturnyi kritik 8 (1936): 113.

Literaturnyi kritik 8 (1936): 113.

RGALI 631.15.78 l. 74.

RGALI 631.15.78 l. 6.

RGALI 631.15.78 l. 6.

RGALI 631.2.140 l. 10. An overview of films planned for 1937 includes screenplays by both Andrei Platonov (“Transport” at Mosfilm) and Viktor Shklovsky (“Mashinist,” at Lenfilm, based on the biography of locomotive driver Petr Krivonos); see V. Usievich, “Plan iubileinogo goda,” Iskusstvo kino 7 (1936): 12–13. Platonov also adapted “Immortality” for the radio, published in: N. Duzhina, “Stantsiia Krasnyi Peregon,” Strana filosofov Andreia Platonova: Problemy tvorchestva (IMLI RAN, 2011) 521–38. There is no record of any of these adaptations being produced.

Letter to M. A. Platonova from February 12, 1936; Andrei Platonov, “…Ia prozhil zhizn’”: Pis’ma (1920–1950 gg.), 410.

A. Platonov, “Bessmertie,” Literaturnyi kritik 8 (1936): 114.

Georg Lukács, “Narrate or Describe?,” Writer and Critic and Other Essays, ed. and trans. Arthur D. Kahn (Grosset and Dunlap, 1971) 111; Georg Lukács, “Erzählen oder Beschreiben? (Zur Diskussion über Naturalismus und Formalismus),” Internationale Literatur 11 (1936): 102. Further references to the English translation and first installment of the German original will be given parenthetically in the text.

On the ways in which socialist realism was originally an open-ended, dialectical aesthetic method (instead of a prescribed style) see: Harold Swayze, Political Control of Literature in the USSR, 1946–1959 (Harvard University Press, 1962), 13–14; Christina Kiaer, “Lyrical Socialist Realism,” October 147 (2014): 56–77; Robert Bird, “Sotsrealism kak teoriia” (Socialist Realism as Theory), Russkaia intellektual’naia revoliutsiia 1910–1930-kh gg., eds. Sergei Zenkin and E. Shumilova (NLO, 2016), 205–21.

G. W. F. Hegel, Werke in zwanzig Bänden (Suhrkamp Verlag, 1969–79) Bd. 9/II. S. 371, 429; cf. G. W. F. Hegel, Philosophy of Nature, trans. A. V. Miller, with Foreword by J. N. Finlay (Clarendon Press, 1970), 303, 350. All translations are my own, unless otherwise noted.

Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), trans. with a Foreword by Martin Nicolaus (Penguin Books, 1973), 105. On “articulation” in Marx, Althusser, and Balibar see Aidan Foster-Carter, “The Modes of Production Controversy,” New Left Review 107 (1978): 53–54.

Lukács, “Narrate or Describe?” 143; “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” Internationale Literatur 12 (1936): 114. In subsequent notes this source will be given as Lukács, “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” pt. 2.

Georg Lukács, “‘Tendency’ or Partisanship?” Essays on Realism, ed. Rodney Livingstone, trans. David Fernbach (MIT Press, 1981), 43.

Lukács, “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” pt. 2, 122.

Lukács, “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” pt. 2, 120.

Lukács, “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” pt. 2, 118.

Lukács, “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” pt. 2, 120.

Georg Lukács, “Emmanuil Levin,” Literaturnoe obozrenie 19–20 (1937): 56. My full translation of this essay appears in the present issue of e-flux journal. As far as I know the German text has been published only once: Georg Lukács, “Die Unsterblichen,” Werke 5: 472–83. The lack of editorial comment and the incorrect title (Olga Halpern’s translation of Platonov’s story was published as “Unsterblichkeit” in Internationale Literatur 3, 1938: 15–29) raise questions about the provenance of the German text.

Lukács, “Emmanuil Levin,” 59.

Lukács, “Emmanuil Levin,” 60.

Lukács, “Emmanuil Levin,” 58.

Platonov, “Bessmertie,” 131. An English translation by Lisa Hayden and Robert Chandler of this story also appears in the present issue of e-flux journal, under the title “Immortality.” On “negativity” in Lukács’s reading of Platonov see also: Artemy Magun, “Otritsatel’naia revoliutsiia Andreia Platonova,” Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie 106 (2010).

Lukács, “Emmanuil Levin,” 56.

Platonov, “Bessmertie,” 125.

Lukács, “Emmanuil Levin,” 57–58.

Lukács, “Emmanuil Levin,” 56.

Lukács, “Emmanuil Levin,” 58.

Platonov, “Bessmertie,” 125.

Platonov, “Bessmertie,” 118.

Platonov, “Bessmertie,” 118.

Platonov, “Bessmertie,” 116.

RGALI 631.15.78 l. 45.

RGALI 631.15.78 ll. 70–71.

V. Shklovskii, “Vzrykhliaia tselinu,” Literaturnaia gazeta, March 15, 1936, 3.

RGALI 631.15.78 l. 45.

Lukács, “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” pt. 2, 119.

Lukács, “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” pt. 2, 119.

RGALI 631.15.78 l. 45.

V. Shklovskii, “Petr Krivonos: Ocherk,” Znamia 12 (1937): 56.

Shklovskii, “Petr Krivonos: Ocherk,” 57.

Shklovskii, “Petr Krivonos: Ocherk,” 60.

Shklovskii, “Petr Krivonos: Ocherk,” 63.

Shklovskii, “Petr Krivonos: Ocherk,” 66.

RGALI 2863.1.699; this is the personal collection of documentary writer Aleksandr Bek.

Andrei Platonov, Fabrika literatury (Vremia, 2011), 463–64.

Platonov, Fabrika literatury, 467.

Platonov, Fabrika literatury, 467.

Shklovskii, “Vzrykhliaia tselinu.”

See Viktor Shklovsky, Third Factory, trans. Richard Sheldon (Dalkey Archive Press, 2002). Cf.: A. Galushkin, “K istorii lichnykh i tvorcheskikh vzaimootnoshenii A. Platonova i V. B. Shklovskogo,” Andrei Platonov: Vospominaniia sovremennikov. Materialy k biografii (Sovremennyi pisatel’, 1994): 172–83; Michael Finke, “The Agit-Flights of Viktor Shklovskii and Boris Pil’niak,” The Other Shore 1 (2010): 19–32.

N. Kornienko, “Soveshchanie v Soiuze pisatelei,” Andrei Platonov, vol. 1 (Sovremennyi pisatel’, 1994), 333.

N. Kornienko, “Soveshchanie v Soiuze pisatelei,” 343.

N. Kornienko, “Soveshchanie v Soiuze pisatelei,” 343.

The homonymy between articulation and dismemberment was earlier recognized by the formalists; see Il’ia Kalinin, “Istoriia kak iskusstvo chlenorazdel’nosti (istoricheskii opyt I meta/literaturnaia praktika russkikh formalistov), Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie 71 (2005): 103–31.

Lukács, “Narrate or Describe?” 112; “Erzählen oder Beschreiben?” Internationale Literatur 11 (1936): 102.

L. N. Tolstoi, Sobranie sochinenii v 22 tomakh (Khudozhestvennaia literatura, 1978–85), vol. 18, 784.

Category

Subject

The author thanks Christina Kiaer for her critique, and audiences at Columbia University and the Literature and Philosophy Workshop at the University of Chicago for their responses to earlier versions of this article.