Gina: Black was not included in that idea.

Juanita: No, that was not the intention.1

In 2016, a potential film location offered me an intriguing combination of circumstances regarding the always-existing questions in filmmaking of the site, the set, and the dimensions of space and time. As a multilayered entity—at once an example of Dutch architectural heritage, a corporate asset, an office workplace, and a home to asylum-seekers in need of a roof and recognition—the Amsterdam office complex Tripolis presented a site through which to explore various levels of colonial-modern here-ness.2

This combination continues to echo as an abiding theme in my work. The following set of meditations considers some of its implications, both in my work filmed in Tripolis, Prologue: Squat/Anti-Squat (2016), and in films by Alain Resnais, Glauber Rocha, and Pedro Costa. These thoughts are inspired by Denise Ferreira da Silva, in particular her essay “The Racial Event,” in which she writes: “I move to abandon temporal thinking, which imposes and necessitates the presumption of separability, and move to read back-then and the over-there as constitutive of what happens right-now and right-here and what is about to happen.”3

I want to consider reading the modern city as a site of colonial-capitalistic struggle and as a “racial event,” using the film edit as a lens.4 I see in filmmaking a possibility to work with the necessary collapse of time and space that Ferreira da Silva calls us to, pointing to what is real here and now by aiming to include all dimensions in cinematic language.

***

Three buildings make up Tripolis, which was designed by the Dutch structuralist architect Aldo van Eyck and his team in 1994. Van Eyck’s respect for the human scale is a well-known characteristic of his architecture. In the 1950s, he and the group of architects called Team X distanced themselves from the large-scale architectural approach of the Conference Internationale d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM). As a large corporate project—providing office space of more than twenty-thousand square meters—Tripolis is therefore uncharacteristic of van Eyck’s work. Nevertheless, its spatial organization carries his spirit of connection and conversation, and his goal of providing a personal experience of space.

In the spring of 2016, We Are Here, a group of people who had been refused official stay in the Netherlands but could neither return to their countries of departure nor go anywhere else, squatted Tripolis 200, one of the three buildings of the complex, for roughly three weeks.5 Ironically, until two years earlier, this part of the complex had been occupied as the municipal office of South Amsterdam through which (accepted) citizens passed to register, get married, and pick up official documents.

The mirror image of Tripolis 200, a building named 300, was also nearly vacant when We Are Here moved in. However, a small number of people were living in a tiny part of Tripolis 300’s newly renovated office spaces. BNP Paribas Investment Partners had moved out quite soon after investing in a grand renovation designed by Fokkema & Partners Architecten only a few years earlier.6 The third building, Tripolis 100, was being rented by the European headquarters of Nikon, which had renovated its part of the complex in 2012 with the Amsterdam-based Japanese architect Moriko Kira.7

The few inhabitants in the vacant building 300 were living there on a contract with an anti-squat—or “vacancy-management”—agency. These agencies have sprung up everywhere in the Netherlands and successfully protect empty property by offering low-rent space with a long set of conditions. Usually the contracts include: being present in the building for a significant part of the time, not having any children or pets, leaving quickly once the place has found a new, “proper” use, and watching out for trespassers.8 About four people had set up bedrooms and kitchens in carpeted boardrooms, spread across six floors, with individual fridges in the main cafeteria space. When We Are Here entered the adjacent Tripolis 200, the anti-squat inhabitants lived up to their task and notified the authorities.

Considering its contemporary existence as a site of a squatting action by We Are Here, which points at some of the most urgent national and urban questions about housing and citizenship today, I wanted to cast Tripolis as a location for a film work. The unlikely combination of this event and the design in the tradition of van Eyck’s socially concerned modernist architecture seemed enough reason to try.

After a failed appointment with a consultant from the real-estate agency Cushman and Wakefield, which was responsible for renting out the empty offices, my team and I met with a daily caretaker. The buildings’ caretakers, who showed a heartfelt fondness for the labyrinthine complex, are employed by Facility Solutions, a firm based just outside Amsterdam. During the buildings’ more prosperous times, Facility Solutions had also delivered janitorial services, but in times of vacancy, Facility Solutions was contracted by the larger property and asset management firm EPOC (European Property Operations Corporation), based in ’s-Hertogenbosch, a city about eighty kilometers from Amsterdam. EPOC was responsible for repurposing the building complex in the service of its owner, the global insurance and equity firm AXA Investment Managers, which has its headquarters in Paris.9

EPOC’s friendly location manager eventually persuaded an account manager from AXA’s Amsterdam office to meet us. This administrator was not responsible for the building, but took on the task of speaking on behalf of AXA’s clients. As it turned out, Tripolis was contained in the portfolio of a German branch of AXA. As such, the circles of management clearly radiated out from a local interest to a global investment level. The janitors and even the EPOC’s location manager for Tripolis neatly navigated between an actual relationship with the architecture and its locality, and an abstract level of responsibility for the property of anonymous investors. They represented the gap between local urban experience and the global property investment boom, a phenomenon that is alienated from the play of light and space, corners and staircases. Toward considering the critical potential within this site, I have below compiled an imaginary montage of three classic and—in their own way—anti-colonial cinemas of time and place.

The Here-ness of El Dorado: Three Cinemas of Time and Place

1.

The first film is Muriel ou le Temps d’un retour, Alain Resnais’s 1963 experimental melodrama about French life in the wake of the Algerian War.10 A key scene opens with shots of houses and cityscapes. Broken and newly constructed. Daytime, nighttime. No specific order or temporal logic. After a sequence of close-ups in movement, with each protagonist glancing in one or another direction—suggesting signals between them—or upwards to the possible rain, they eventually arrive at the lit-up entrance to a modern apartment building.

—It looks newly built. Is that because of the war?

—A bombed city.

—Yes.

—There were many dead, executed. I don’t remember the numbers: 200? 3000? I really don’t remember.

Rapid consecutive shots show signs pointing to a cemetery, a monument to a fallen hero, street names relating to fighting, resistance, World War II, and colonial wars. The setting—the town of Boulogne-sur-Mer—is as much a character as any of the humans in Muriel. All its characters carry memories that haunt or taint the present. Throughout the film, the reconstructed cityscapes are woven together with the obsessions, lies, and fears of a small postwar bourgeois group. Fragmentary cutting between images of modern housing projects and daily conversations eventually exposes secret habits and betrayals, but never explains the sequence of events or the exact passing of time. In this film, the collapsing of time that defines all film editing is made material: a concept we can grasp, chew on, understand. In the very materiality of the film, space collapses as well. Damaged super-8 shots from Algiers appear between the filmed scenes of destruction and reconstruction in a seaside town in Europe. Continuity and logic are playfully neglected in the combination of locations.

Muriel was released shortly after the end of the Algerian War of Independence. One of the characters, the young Bernard, has just returned from this war and brings guilt and trauma home with him. The promise that this town’s new architecture in the alternating shots expresses is interlocked with the film’s suggestion that, in the early 1960s, those same promising spaces were filled with the ghosts of wartime and colonial atrocity. Specters of violence and colonial repression had arisen in many European cities around that time: the effects of colonialism washing up on European shores via increasing migration from the former colonies to the metropoles. This process of return was also implied in European modern architecture. In particular, the urgently needed postwar housing projects in European cities were tightly entangled with city developments in North Africa, where French urban planners had already tested their innovative ideas.

The notes from the first International Congress on Urbanism in the Colonies in 1932 state: “It is through colonial urbanism that urbanism has penetrated into France.”11 At the 1953 CIAM meeting, where concerns for building “housing for the greater number” were defined in a Charter of Habitat that was specifically based on designs for Moroccan cities, the younger members of the congress, including Aldo van Eyck, went on to form the group Team X. In critical response to the charter, they prepared adjustments to it for the next CIAM meeting, which was supposed to take place in Algiers in 1955. The meeting did not happen there due to unrest that had broken out. These CIAM meetings, not to mention cheap labor from the former colonies, had great influence on modern architecture developing in France, the UK, and the Netherlands. Today, many modernist projects in these European countries are inhabited by various communities from the formerly colonial territories.

Resnais’s jumping edits in Muriel connect the conversations of the protagonists, who seem in constant movement, and the architecture in Boulogne-sur-Mer, which suffered from destruction during World War II and was in the process of being replaced by modern urbanism. This editing strategy contributes to a feeling of instability and the presence of unsettling traces. In the filmic reality, the imagined distant colony over-there collapses into the here. The presumed back-then of colonial time collapses into the now.12

Stills from Alain Resnais’s 1963 movie Muriel ou le Temps d’un retour.

Stills from Alain Resnais’s 1963 movie Muriel ou le Temps d’un retour.

2.

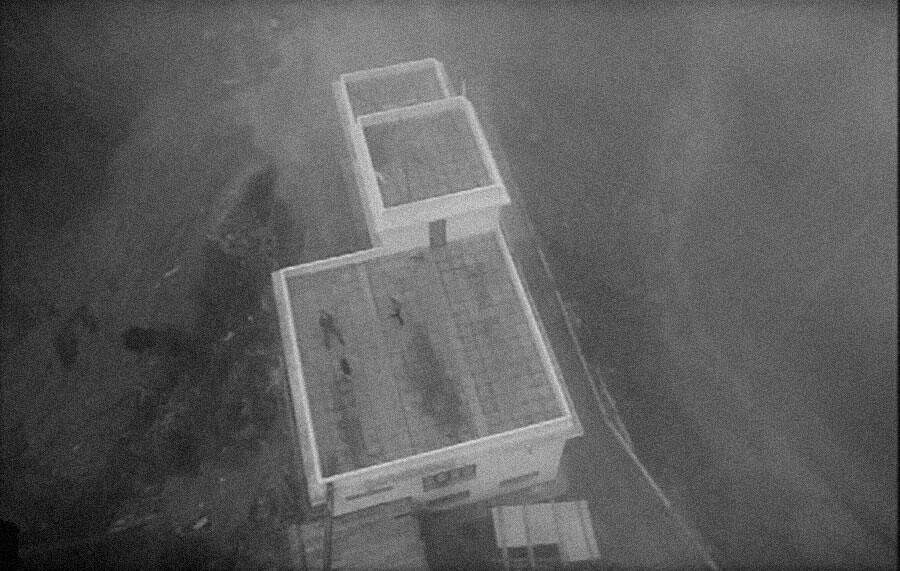

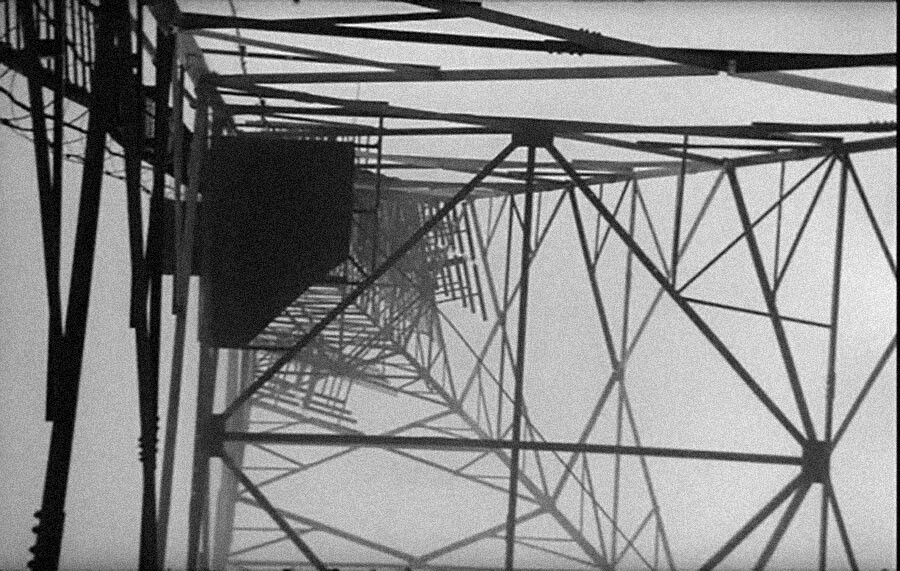

Whereas Resnais’s Muriel was produced in the shadow of war “elsewhere,” Glauber Rocha managed to realize his explicitly political allegory, Terra em Transe (1967), under Brazil’s fully implemented repressive dictatorship. In the middle of the film, an upward shot of a television transmission tower is followed by an aerial shot of a modern villa. The two structures, indicating modernity and technological development, relate to the character of Fuentes, who represents the progressive bourgeoisie. He is the modern face of the ruling class in the fictional country of El Dorado. He is a dynamic entrepreneur who owns the country’s most important factories and mines, controls the cultural industry, and animates high society with his capital. On a modernist rooftop in a misty landscape under the television tower, he leans back in his chair, smiles vainly, and talks to Paulo, the poet and main character of the film, about his power: “I import the best equipment … I do great campaigns … I had dinner at the embassy.”

In voice-over narration, Paulo explains that Fuentes visits his ambassador friend at the embassy every day. They discuss tropical plants: “I imported some seeds, marvelous … I’ve got some credit again from the National Bank.”

But after Fuentes finds out that the ambassador has left the country and betrayed him on a promised deal, he addresses the camera and expresses disappointment: “What’s the use of working? I want to develop this little country! I promote the arts, I perform acts of charity, I do useful things!”

Property, politics, plant seeds, and the arts are claimed in the same breath by the progressive entrepreneur at the heart of Terra em Transe. Made in the wake of Brazil’s 1964 coup, the film meditates upon the “trance” of neoliberal politics, as though a form of magic creates the figures of both a political “left” and “right.” Populism was a strategy that both the left and right leaned on heavily at the time, and the film suggests that the desire to include the masses depends on the forces of the unconscious, the magical, and the trance that held the country in its grip. Within this framework, political leadership was legitimated through charisma rather than through effective programs of reform according to solid principles.13 In the film’s fictional time and place, both the left and right work with this force, as was the case in Brazil in the late 1960s. In today’s political landscape, we feel the forces of the magical played upon more successfully by the new right, but the dilemmas of the left that the film displays are still recognizable.

The main motivation of the film’s images is to express the artist and poet Paulo’s guilt and inner conflict with respect to his alliances and political choices. Paulo is a channel through which these contradictions of politics and charisma are lived and expressed. Through Paulo, Rocha directly confesses his own conflicted position as an artist within a political and economic structure that he tries to move against. Brazilian cinema scholar Ismail Xavier suggests that

the essential problem faced by Paulo is, in fact, the divorce between his poetry and his social engagement. His poems display an anachronistic eloquence and usually betray a pessimism that seems to undermine all of his gestures of political commitment. The verses bring melancholy, disgust, and a sense of decay.14

Whereas Resnais’s Muriel works through questions of power and personal struggles via an experimental spatiotemporal edit, Terra em Transe draws its viewers into a direct relationship with the most concrete and architectural signs of modernity through a mixture of abstract, stylized scenes, at times with frenzied energy. Rocha creates an awareness of the mediated nature of reality by constantly reminding the viewer of the filmic mode of production. For example, the effect of estrangement is achieved when characters suddenly address the camera, or when a television item introducing the conservative leader becomes part of the story of the film.

Shifting among a cast of characters, including a right-wing demagogue, a left-wing political puppet, a tormented poet, and a progressive entrepreneur, Rocha maneuvers his viewers through scenes of political deliberation that are constantly swamped by affective and oneiric experiences. Rocha’s frenzied aesthetics show an emotional response to the political, apparently inheriting the forces of the unconscious and the magical from colonial modernity. Today those forces seem to reappear as inescapable figures of our contemporary neoliberal global malaise.

Stills from Glauber Rocha’s 1967 movie Terra em Transe.

Stills from Glauber Rocha’s 1967 movie Terra em Transe.

3.

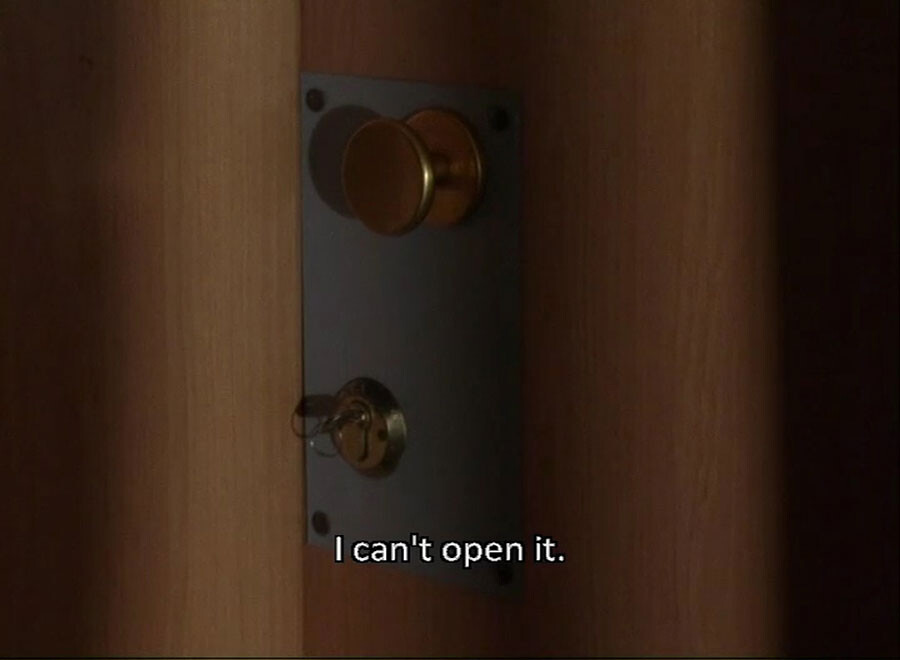

In a central scene from our third film in this imaginary montage, Colossal Youth (2006) by Pedro Costa, an older man appears desolate in front of a stark white building complex. We only see his head. Walls with small, shuttered windows rise up behind him. Another man approaches, greets him, and introduces himself as the building administrator, mentioning that his previous occupation was as a locksmith. The older man, who is known by his nickname, Ventura, states that he is a retired laborer. They establish that they come from opposite sides of the island group Cape Verde. Having so far addressed each other in Cape Verdean Creole, the administrator, after a pause, looks at his watch and declares in Portuguese: “3pm, November 2001. Fourth floor on the right. The flat is full of light.”

The white buildings are new flats in a government-planned housing settlement in Lisbon. For some inhabitants, the new buildings are meant to replace homes they had built for themselves in the informal neighborhood of Fontainhas, which was bulldozed around the time Pedro Costa filmed Colossal Youth in 2006. The film moves between the last spaces still standing in Fontainhas and the new building complex and its interiors.

Over the course of three films in nine years (1997–2006), Pedro Costa established a cinematic language that moves aesthetically between the inner and outer worlds of the people who live in marginalized and precarious circumstances in the city of Lisbon.15 Through long takes and precise compositions with beautiful lighting, the protagonists appear in their own environments and with their own words. At times, these words have clearly been rehearsed, and are recited in a poetic way. In other scenes, words seem to be spoken spontaneously, with the camera just waiting for a conversation to unfold. In Colossal Youth, it is the character of Ventura, the elderly man from Cape Verde, who leads the experimental narrative.

Plot does not necessarily motivate the film’s long single-take scenes (although some stories about the characters do unfold); rather, these scenes seem to be driven by the different spaces that the characters move between and reside in. Through Ventura’s character we observe and live the dilemmas of habitation: “housing” as a grand social architectural gesture versus the “home” in informal developments. “It is simply too small,” Ventura remarks of the three-bedroom apartment he is shown by the administrator. The administrator recites an endless list of the rules and regulations of inhabitation as he shows the new and bright-white flat.

Other characters reappear across Costa’s films, like the central character Vanda Duarte from In Vanda’s Room (2001). Over years of friendship and work with his real-life protagonists, Costa has created “screen subjects” whose lives can be experienced through a “cinema of poetry.”16 The cinematic experience connects an audience to spaces constructed and affected by the dissonant organization of the colonial present—to spaces that speak of Ferreira da Silva’s “racial event.” In Costa’s films, as in Resnais’s (albeit with a very different approach), we feel the collapse of the imagined distance between now and a colonial over-there and back-then.

Stills from Pedro Costa’s 2006 movie Colossal Youth.

Stills from Pedro Costa’s 2006 movie Colossal Youth.

The Squat as Site and Set

We are back in Tripolis, the van Eyck building where my shoot eventually took place.17 In the now-completed film, over images of the empty spaces we hear a conversation about the lucrative business of anti-squatting agencies, about how the concept has become a Dutch export product and is disrupting formerly protective housing laws in the Netherlands. Slowly, the talk turns towards the 1970s, when squatting was still a possible political gesture and tool. The cast, whose conversations make up the soundtrack of the film, consists of activists and squatters from different generations and different backgrounds, with different experiences of occupying spaces that were not officially granted to them. In small groups throughout the various rooms of the buildings, they discuss topics that concern them all. One room has a pencil drawing on the wall—an obvious leftover from the recent short-lived occupation—with the words “WE ARE HERE.”

In one scene, the entire cast watches an archival movie from 1979 in which an elegant Surinamese woman talks about the housing situation she faced when she arrived in the Netherlands. She explains how she and others decided to squat the empty flats that were denied to members of her community because of racist housing policies. These flats were part of a huge new housing complex called the Bijlmer on the southeast side of Amsterdam, which boasted a modern way of living among spacious green common areas, with parking structures and road systems.

Still from Wendelien van Oldenborgh, Prologue: Squat/Anti-Squat, 2016.

Developed for the middle classes, the flats stayed empty because construction of the necessary daily infrastructure, like public transport and shops, was delayed. Corrupt landlords were getting state funding to rent small, dilapidated, and overcrowded boarding houses to the newly arriving Caribbean Dutch community, yet they were prevented from moving into the large, sunny, vacant flats in the Bijlmer. There was a set percentage of black people allowed to live in certain city areas, while others were totally off limits to people of color. And yet the rent for one of the large flats would equal—or even be less than—what the state was paying for a whole family to live in one room of a boarding house.

Squatting was a solution at the time. Through continuous action, the political point was made. In the archival movie screened at Tripolis, Oema foe Sranan (Women of Suriname, 1979), produced by Cineclub Vrijheids Films (Cineclub Freedom Films), the titular woman laconically relates the story of her struggle for housing. But when she recalls a protest at city hall, her laughter is infectious: “When we got there we were told that the mayor was hospitable. But that was a strange hospitality,” she says. “Instead of a welcome with wine and cognac, we were awaited by bulldogs!”

Although the history of squatting forms part of Amsterdam’s proud image as the progressive center of the Netherlands, history usually omits the actions of this Caribbean Dutch group. At the time, they were supported by and collaborated with various other squatter movements, which were predominately white. But finding housing by squatting did not solve the problem of systematic exclusion and distancing, and in 2016 the action in Tripolis carried out by We Are Here was cut short. Squatting has been criminalized in the Netherlands since 2010, and the asset value of Tripolis, protected by the anti-squatting inhabitants, added to the tension.

When a site full of tension becomes a set for a film, it can disrupt the “proper” ordering of time and space. Tripolis exists as a prime example of a contemporary, complex confluence of site, territority, and legality: an office workplace, a home to asylum-seekers, and a corporate asset. Its value goes up as long as one of these is excluded—edited out. As much as a method for cancelling out, omitting, or excluding, filmic montage also provides an opportunity to structure and thereby question and affect the temporal thinking that supports those very exclusions.

Gina Lafour, student and activist, and Juanita Lalji, former member of the National Organization of Surinamese in the Netherlands (LOSON), in dialogue. From Wendelien van Oldenborgh, Prologue: Squat/Anti-Squat, 2016.

The term “colonial-modern” refers to the title of a book that was influential in thinking about this essay: Colonial Modern: Aesthetics of the Past, Rebellions for the Future, eds. Tom Avermaete, Serhat Karakayali, and Marion von Osten (Black Dog, 2010).

Denise Ferreira da Silva, “The Racial Event or that Which Happens Without Time,” in The Two-Sided Lake: Scenarios, Storyboards and Sets from Liverpool Biennial 2016 (Liverpool University Press, 2017).

The term “colonial-capitalistic” is introduced by Suely Rolnik in her inspiring text “The Spheres of Insurrection: Suggestions for Combating the Pimping of Life,” e-flux journal 86, (November 2017) →. In addition, the way “’reading” is meant here is informed by Denise Ferreira da Silva and Valentina Desideri’s concept of “poethical readings.”

See →.

See →.

The anti-squat agency for Tripolis was De Zwerfkei, who pride themselves on having introduced anti-squatting thirty years ago. See →.

Since that time, EPOC has changed its name to Bright!, and in July 2017 AXA sold Tripolis to the New York-based “multinational private equity, alternative asset management and financial service group” Blackstone, for six million euros less than what they had paid for it in 2003. See → (in Dutch). For Blackstone, see →.

In a 1963 review in Film Quarterly, Susan Sontag wrote of Resnais’s film: “It attempts to deal with substantive issues—war guilt over Algeria, the OAS, the racism of the colonies … But it also attempts to project a purely abstract drama.”

Tom Avermaete, “Nomadic Experts and Travelling Perspectives: Colonial Modernity and the Epistemological Shift in Modern Architectural Culture,” in Colonial Modern.

For elaboration on this “back-then” and “over-there” as constant attempts to separate ourselves from colonial space and time, see Ferreira da Silva, “The Racial Event.”

See Ismail Xavier, Allegories of Underdevelopment: Aesthetics and Politics in Modern Brazilian Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 1997).

Xavier, Allegories of Underdevelopment.

Pedro Costa’s three main films about Fontainhas are Ossos (1997), In Vanda’s Room (2000), and Colossal Youth (2006).

Pier Paolo Pasolini theorized cinema as a language system that is fundamentally irrational and related to memories and dreams. See The “Cinema of Poetry” in Pasolini, Heretical Empiricism (New Academia Publishing, 1972), 172–73.

Wendelien van Oldenborgh, Prologue: Squat/Anti-Squat, 2016, with Khadija Al’Morabid, Quinsy Gario, Hellen Felter, Roel Griffioen, Lucien Lafour, Gina Lafour, Juanita Lalji, André Reeder, University of Colour: Max de Ploeg and Tirza, Kees Visser.