Voices from the beach can be hard to hear. They can be snatched from the lips by the wind or drowned in the white noise of the waves. But there are beaches, too, on which voices are hard to hear because of the silence.

—Greg Denning, Beach Crossings: Voyaging across Times, Cultures, and Self

Beaches remain important places within Indigenous coastal peoples’ territories, though the silence about our ownership is deafening. The coastline of the Australian continent was frequented for centuries by mariners and traders from Asia with whom some Indigenous groups established trade and familial relations.1 The first verified contact by Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon was in March 1606; he chartered the west coast of Cape York Peninsula in northern Queensland. Over the next two centuries the charting of the Australian coastline was primarily undertaken by British explorers. Since 1788, the coastline of this continent has been colonized by British colonists and their descendants, who built the majority of Australia’s capital cities near the sea. In 2010, it is where the largest proportion of the Australian population resides on the most prized real estate in the country. Living near the sea ensures that the beach continues to be a place of multiple encounters for residents and visitors. The beach marks the border between land and sea, between one nation and another, a place that stands as the common ground upon which collective national ownership, memory, and identity are on public display; a place of pleasure, leisure, and pride. Michael Taussig argues that the beach is a site of fantasy production, a playground where transgressions and pleasure occur. It is “the ultimate fantasy where nature and carnival blend as prehistory in the dialectical image of modernity.”2

As an island continent, beaches are the visible terra manifestation of Australian borders, which operate simultaneously to include and exclude. In the twenty-first century, these borders may seem to be more permeable because of economic and cultural processes of globalization, but territorial sovereignty reigns supreme in Australia and Europe, evidenced by border patrols that serve to exclude those who are uninvited. Within Australia we are constantly reminded of the central role of possession in civilizing “others” and the association between war and borders, which is reinscribed through our treatment of asylum seekers who travel by boat attempting to land on our beaches. Australian federal governments have built mandatory detention centers fenced with razor wire and patrolled by guards to accommodate the “illegal boat people” who have been successful in landing on our beaches after escaping from war-torn countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan. In taking possession of their bodies and imprisoning them, the nation-state exercises its sovereignty in violation of several human rights conventions that it has signed. This performative sovereign act of violence and disavowal has historical roots. Despite international law, the British invasion, in the form and arrival of the first naval boat people, produced invisible borders left in the wake of colonization that continues to deny Indigenous people our sovereign rights. Many authors have argued that within Australian popular culture the beach is a key site where racialized and gendered transgressions, fantasies, and desires are played out, but none have elucidated that these cultural practices reiteratively signify that the nation is a white possession.3

In this text I examine how white possession functions ontologically and performatively within Australian beach culture through the white male body. I draw on Judith Butler’s idea of performativity in that a culturally determined and historically contingent act, which is internally discontinuous, is only real to the extent that it is repeated.4 Raced and gendered norms of subjectivity are iterated in different ways through performative repetition in specific historical and cultural contexts. National racial and sexual subjects are in this sense both doings and things done, but where I differ from Butler is that I argue that they are existentially and ontologically tied to patriarchal white sovereignty. Patriarchal white sovereignty is a regime of power that derives from the illegal act of possession and is most acutely manifested in the form of the Crown and the judiciary, but it is also evident in everyday cultural practices and spaces. As a means of controlling differently racialized populations enclosed within the borders of a given society, white subjects are disciplined, though to different degrees, to invest in the nation as their possession. As a regime of power, patriarchal white sovereignty capillaries the performative reiteration of white possession through white male bodies. In this way performativity functions as a disciplinary technique that enables the white male subject to be imbued with a sense of belonging and ownership produced by a possessive logic that presupposes cultural familiarity and commonality applied to social action. In this context I will examine how the beach is appropriated as a white possession through the performative reiteration of the white male body. I then discuss how Indigenous artist Vernon Ah Kee contests this performativity in his installation entitled Cant Chant.

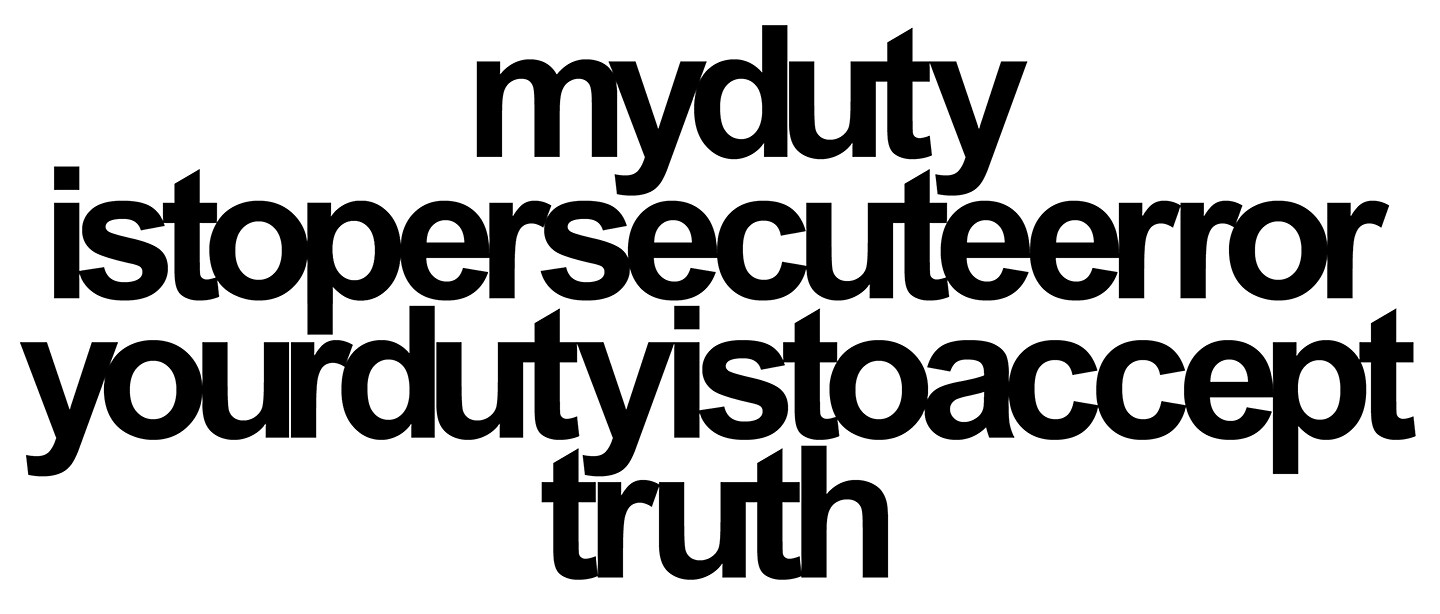

Vernon Ah Kee, acceptance, 2005. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane.

Performing the Colonial Subject

Colonization is the historical process through which the performativity of the white male body and its relationship to the environment has been realized and defined, particularly in former British colonies such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.5 In staking possession to Indigenous lands, white male bodies were taking control and ownership of the environments they encountered by mapping land and naming places, which is an integral part of the colonizing process. One of the first possessive performances by the white male body occurred on the beach when Captain James Cook landed at a place he named Botany Bay on April 28, 1770. For some time his boat had been under surveillance by the Kamegal clan of Cooks River and Botany areas and the Gwegal clan at Kundull (Kurnell). At first the Kamegal and Gwegal clans thought the large boat was a big bird entering the bay, but as the boat approached they could see that the people onboard were similar but different to themselves.6 When Cook and his men landed on the beach at Kundull, they were trespassing on Gwegal land and hence were challenged by two Gwegal warriors who threw spears at them while shouting out in their language “Warra Warra Wai,” meaning “go away.” Cook’s crew retaliated by firing muskets and wounding one of the Gwegal warriors. The warriors retreated, leaving their spears and shields behind on the ground. This encounter was never interpreted as an act of Indigenous sovereignty by Cook as he made his way up the eastern coast of Australia. Instead, he rescripted us as living in a state of nature with no knowledge of, or possession of, proprietary rights.7

Cook took possession of the Gwegal warriors’ weapons and transported them back to Britain, where they are now on display in a museum housing the property of people from different countries accumulated through purchase, plunder, and theft. After eight days in Botany Bay, Cook and his crew sailed north up the coastline of Australia. Cook made good use of his telescope, surveying the Indigenous people on the beach as he sailed past their lands, noting in his diaries that we ranged in color from chocolate to soot. After several months of sailing northward, he eventually took possession of the entire eastern coast from the 38 degree latitude in the name of King George III after landing on the beach of an island he named “Possession,” situated off the tip of Cape York Peninsula. The assumption of sovereignty was ceremoniously marked by firing guns and raising the British flag as the male crew bore witness. The performative act of possession enabled by patriarchal white sovereignty is constituted by violence and transgression, voyeurism, pleasure, and pride. These originary performative acts by the white male body would eventually become an integral part of Australian beach culture.

Some eight years after Cook, eleven British naval ships arrived in Botany Bay. Governor Phillip, as the embodiment of colonial power, planted a British flag in the sand, staking a possessive claim to lands that belonged to the Eora and Gadigal nations. The invasion had begun and the lives of the people from the Kamegal and Gwegal clans were never the same as violence and smallpox took its toll. Over the next century, through containment, disease, and death, Indigenous people were displaced by colonists. In the white colonial imagination, we had become abject subjects; our lives and our bodies were physically erased from the beach.8 Over the next century the only subjects who determined which bodies mattered on the beach were almost exclusively white males, embodying the possessive prerogative of patriarchal white sovereignty as a colonial norm.9

Despite the apparent promise of open access and use, public spaces are predicated upon an assumption of objectivity and rationality, which values but no longer explicitly marks or names whiteness or maleness. The beach, as a public space, continues to be controlled by white men, the embodiment of universal humanness and national identity. In the nineteenth century, the beach and its natural features were mostly of interest to white male visitors who were influenced by European Romanticism. The beauty of the beach appealed to observers, along with “its sublime features: those characteristics which stimulated an intensity of emotion and sensation [valuing] poetic mystery above intellectual clarity.”10 Perceived as such, the beach enabled the performance of a gendered white ontological experience where nature fed the soul and culture nurtured white men’s sensibilities. The beach was also an intersubjective place where a man could socialize with family and friends or watch other beachgoers and indulge in the British custom of promenading along the shore. The beach was and remains a heteronormative white masculine space entailing performances of sexuality, wealth, voyeurism, class, and possession. However, these different attributes of white male performativity underwent a transformation with the introduction of surf bathing. In the nineteenth century, surf bathing was performed exclusively by white males, but it was not a predominant part of beach culture because the Police Act 1838 restricted swimming to the early hours of the morning and preferably on nonpopular beaches. The public display of the white male body was perceived to offend moral sensibilities current at the time. It was not until the early twentieth century that surf bathing became a part of modern beach culture, due in part to the shifting codes of Victorian morality and increased control of the sea and the surf.11 Eugenics also played a part in the shift. “Whereas picnicking and promenading defined masculinity in terms of an emphasis on the respectability and moral authority of colonialism, surf bathing and lifesaving defined masculinity in terms of a strong, fit, well muscled and racially pure white body.”12 This representation of the white male body was in contrast to the perception of policymakers at the turn of the century, who facilitated the displacement of the Indigenous body from the beaches and lands onto reserves and missions. The Indigenous body was represented as being terminal. The common phrase at the time to describe the containment and removal was as a benevolent act of “smoothing the dying pillow.”13

Vernon Ah Kee, acceptance, 2005. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane.

Beach Lifesavers: Performing White Masculinity

By 1907, white middle-class men had formed the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia in response to the public representation of their surf bathing as being an “affront to decency.”14 They soon gained public approval by rationalizing their objectives as humanitarian and arguing that surf bathing was a disciplined organized sport involving military drills. Unlike lifeguards, who were paid for their services, surf lifesavers were volunteers who undertook training to protect people on the beach and were responsible for the safety and rescue of swimmers, surfers, and other water-sports participants. Regimentation, rigor, and dedication to the service of the nation produced fit and disciplined white male bodies. The media reported favorably on the suntanned white male bodies, representing them as the epitome of Australian manhood. Suntanning enhanced the aesthetic modalities of the white male body appropriating and domesticating the hypersexuality signified by black skin. Tanning simultaneously renders the presence of color as a temporary alteration that works to affirm the dominance of white masculinity and its ownership of the beach. The brownness of the white male body becomes “a detachable signifier, inessential to the subject, and hence acceptable” because it is not permanent.15 As a detached signifier, it does not disrupt the “somatic luxury of white [male] subjects to roam and return to the tabula rasa of ideal whiteness where it is conveniently restored to its apex of privileges” as the embodiment of nation.16 The surf lifesaver’s discipline, strength, bravery, mateship, loyalty, and rigor embodied the attributes of white national identity, which were later ascribed to the body of the digger at ANZAC. The term “digger” is an appellation applied to Australian and New Zealand soldiers because of their trench-digging activities during the Gallipoli campaign, which required strong and fit bodies to undertake the hard work. The transference of the attributes of the surf lifesaver to the digger was not a coincidence. Many surf lifesavers volunteered for both world wars, and in some cases lifesaving clubs were closed because of the declining numbers of young men.17

The suntanned and hypermasculinized white body of the digger became inextricably tied to the birth of Australian nationalism within the white imaginary in the late twentieth century. This national identification with the performativity of invasion and taking possession of other peoples’ lands embraces and legitimizes a tradition of patriarchal white sovereign violence embodied in the white male body on the beach in Australia and abroad. More than fifty thousand Australian soldiers volunteered to go to war in Europe to defend the sovereignty of the British Empire, an empire that was founded on the invasion and theft of Indigenous peoples lands. The first convoy of predominantly white male volunteers left Western Australia in November 1914, arriving on the beach at Gallipoli on April 25. Staking a possessive claim to the beach, Lieutenant General Sir William Birdwood, on April 29, 1915, decided to name the area ANZAC Cove in honor of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps who served at Gallipoli. Despite this possessive claim, the Turkish government did not agree to officially name the site ANZAC Cove for another seventy years, due in part as a gesture of goodwill and respect tied to the Australian government’s funding package to maintain the site. At that fateful site, the Turkish army decimated the Australian and New Zealand armies and thousands of soldiers lost their lives. Though Gallipoli was a spectacular strategic blunder, Fiona Nicoll, in her excellent book From Diggers to Drag Queens: Reconfiguring National Identity,18 explores how the body of the white male soldier was constructed as a metonym for the ANZAC spirit, which has increasingly divested the digger of its origins in values of militarism and racial supremacy. The digger’s white male body signified egalitarianism, discipline, irreverence, bravery, endurance, and constitutional opposition to authority. As Nicoll argues, the diggers’ hypermasculinized and idealized body in cultural representations was in contrast to the actual traumatized and disfigured white male bodies returning home.

Following the carnage of the Great War, the lifesaver was used as a signifier of national identity to endow the broken body of the digger with new life and new masculine virility. During the interwar period and up to the 1950s, media represented the white male body of the surf lifesaver as the embodiment of the ANZAC spirit and the nation. In 1923, the president of the Surf Life Saving Association stated in the Daily Guardian that “we shall rear a race of men finer than the Anzacs, whom the whole world admire[s].”19 And in 1941, the commentary in a newsreel item shot at a Bondi Beach carnival stated that “mighty deeds spawn men of might. This is the crucible from which fighting material emerges volunteer lifesavers, volunteer fighters. The amateur surf clubs have an enlistment record second to none.”20 The embodied signification of the white surf lifesavers as nation is also demonstrated by their inclusion and performance in national events such as the opening of the Harbour Bridge in Sydney in 1932, the Australian sesquicentenary in 1938, Queen Elizabeth’s visit in 1954, and the Melbourne Olympics in 1956. During the 1940s, photographer Max Dupain captured Australian beach culture in his representations of white male bodies in photographs that include the infamous Sunbaker (1937), Surf Race Start (1940), and Surfs Up (1940). Dupain’s portraits of white male bodies performing in the service of the nation represented the beach as a white possession, a space of leisure, pleasure, and pride.

In the 1930s, surf lifesaving clubs were conferred with a legal proprietary right to the beaches by local councils, which officially gave them the power to control, police, and rescue beachgoers. Despite the official sanction of surf lifesavers’ ownership of the beach, their proprietorship was challenged after World War II through the emergence of a new white masculinity in the form of the surfer. In public discourse, surfing was represented as a form of hedonistic leisure, evoking anxiety about the moral decay of young men and women. Surfing produced a competitive, individualized white form of masculinity that attracted more women onto the beach. This hedonistic form of leisure was in contrast to the volunteer surf lifesavers who patrolled the beach and saved lives in the service of the nation. In the 1960s, surf lifesaving clubs attempted to restrict surfers’ use of the beach by imposing taxes and restricting the use of surfboards to certain areas. Surfers responded by establishing “administrative associations to regulate, codify and legitimize what they now defined as a sport” in order to stake a possessive claim to the beach.21 During the 1960s and 1970s, tension existed and violence occurred between these two forms of embodied white masculinity on the beach, usually over territory and sexual access to women as well as prowess in the water. Verbal abuse on the beach was common: surfers taunted lifesavers by calling them “seals” because of their regimented training, “dickheads” because their caps looked like the heads of condoms, and “budgie smugglers” because their swimming attire exhibited the outline of small male genitalia, particularly on cold days. Surf lifesavers responded to surfers by calling them “seaweed” because of their long, bleached, matted hair and their supposed inability to master the waves. These white heterosexual territorial wars abated to some degree when surfing was recognized nationally as a professional sport through organized professional tournaments that were covered by media and sponsored by corporations. Similarly, surf lifesaving became recognized as a professional sport predominantly through the “Iron Man” tournaments sponsored by corporations. The sexualized white male body of the suntanned surfer and the lifesaver was commodified to sell everything from Coca Cola to fashion and spawned a new genre of documentary surfing films and televised sport.

White male participation in surfing had begun in the 1930s, but but it did not begin to dominate the surfing scene until the 1960s. Booth argues that after the World War II mass consumer capitalism created the conditions by which leisure as a social practice became tied to individual lifestyles.22 Surfing was and continues to be a native Hawaiian cultural practice introduced to the West by Duke Kahanamoku. Native Hawaiians’ form of surfing was to flow with the waves, adhering to an ideal of soul surfing, which was part of their culture for more than fifteen hundred years.23 Surfing was not considered to be a competitive practice, and when white Australian and South African surfers decided to invade the Native Hawaiian surfing beach of the North Shore of Oahu in the late 1970s, they were confronted by members of Hui ‘O He’e Nalu, who asserted their sovereignty over the beach. For the Native Hawaiian surfers, the invasion of their beach by white surfers was a performative reiteration of the invasion by white American Marines supporting the white patriarchy that overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy in 1890. Native Hawaiian surfer resistance eventually earned the respect of the International Professional Surfing Organization, which conceded to a reduction in annual competitions at North Shore. Despite the assertion of Native Hawaiian sovereignty over the waves and the beaches, white Australian and South African surfers staked a possessive claim, colonizing surfing by riding the waves, “conquering,” “attacking,” and reducing them to stages on which to perform aggressive acts. This became the dominant form of professional surfing, whereby surfers represented their respective nations, embodying the violent attributes of patriarchal white sovereignty.

By the 1980s, the blonde-haired, barrel-chested, suntanned white male body sauntering in board shorts and thongs had become a new icon of beach culture, reflecting the hedonism of youth in the 1960s and 1970s in Australia. The hedonism of surfing carried with it sex, sun, and surf. This was captured in paintings by artists such as Brett Whiteley, whose reclining nudes and bikini-clad beauties on the beach reflected a theater of indolence. In the catalogue for the Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition entitled “On the Beach: With Brett Whiteley and Fellow Australian Artists,” it states that “it was not only the allure of these inherently erotic bodies [in] languid stupor that compelled Whiteley’s fascination for this iconic aspect of Australian landscape; it was also the beautiful vistas of beach and seascapes which provided such fertile ground for his inspirational paintings and drawings.”24 As the embodiment of patriarchal white sovereignty, Whiteley, like the surfers and lifesavers, performatively exhibits the possession of white women’s bodies on “their” beach. While white women are subject to the possessive white male gaze, their presence on the beach is tied to the heteronormativity of patriarchal white sovereignty. They can stake a possessive claim to the beach in ways in which Indigenous women cannot. As I have argued elsewhere, white women have access to power and privilege on the basis of their race through unequal gendered relations.25

After the economic downturn of the 1980s and a decade of multiculturalism and Indigenous rights claims, the militarized white male body of the digger as the embodiment of nation was returned to the beach within the national imaginary. Former prime minister John Howard strategically deployed the memory of Edward “Weary” Dunlop as the quintessential digger, who represented the core national values of mateship and egalitarianism.26 Dunlop was a fearless and strong leader, a qualified surgeon who achieved sporting and military success.27 Taken as a prisoner of war during World War II, he attended to his comrades, risking his own life by challenging his Japanese captors to provide medical provisions for the sick and wounded. He continued to campaign for the rights of soldiers after the war and was a committed humanitarian. Like Howard, former Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating also used the digger in nationalist rhetoric, but he did so in a different way. As Nicoll argues, Keating’s eulogy to the “unknown” soldier “presented … a figure capable of drawing the diverse threads comprising contemporary Australian society together in tolerance.”28 In his attempt to reorient Australia’s core values toward a postcolonial future, Keating performed the digger by walking the Kokoda Trail in the ex-colony of Papua New Guinea, relocating the white male body in the Pacific and away from Europe. As the embodied representation of patriarchal white sovereignty, Keating was also signifying Australia’s role as a former colonizing nation that served to displace and negate the ongoing colonization within the nation.

Following Keating’s performance, John Howard visited the majority of overseas Australian war memorials, where his conveyance of respect was televised to the nation. In particular, he carried a diary belonging to a family member when he visited French battlefields, signifying to the nation that he too had been touched by war. Howard legitimated his authority as an Australian leader of the nation by vicariously linking himself to the digger tradition through his family’s wartime contribution. He strategically deployed the digger nationalism connecting World War I to Timor and then Iraq to substantiate our involvement in war by frequently using the term “digger” in his speeches.29 Howard was at ANZAC Cove, Gallipoli, when a contingent of Australian troops arrived in Muthanna Province, in southern Iraq, on April 25, 2005.30 Howard’s performative reiterations of digger nationalist subjectivity to justify Australia’s deployment in Iraq, in the name of patriarchal white sovereignty, perpetuates the historical connection of the white male body to possession and war. Howard’s militarization of Australian history through the digger rescripted nationalism and resulted in an unprecedented rise in attendance by predominately white youth at memorial services above the beach at ANZAC Cove during his time in office. The somber respect shown at the memorial service at ANZAC Cove performatively reiterates the relationship between the white male body, possession, and war in the defense of patriarchal white sovereignty signified by the place of encounter: the beach.

In Australia, on December 11, 2005, the beach once again became a place where transgression, violence, and white possession were on display. On that day at Cronulla Beach, approximately five thousand predominately white men rioted over the alleged bashing of a surf lifesaver by an Arabic-speaking youth. The racialized production of the “terrorist” as an internal and external threat to the nation after the 9/11 attacks and the bombings in Bali provides a context within which to understand the Cronulla protesters’ rearticulation of white Australians’ possessive claims on the beach as their sovereign ground.31 This is most clearly signified by the pervasiveness of wearing and waving the Australian flag, explicit claims to white possession on T-shirts, inscribed on torsos with body paint, and written on placards waved before media cameras during the protest, such as “We Grew Here: You Flew Here,” “We’re full, fuck off,” “Respect locals or piss off,” and the sign written on the beach for the overhead cameras, “100% Aussie Pride.” The white male body became the signifier of protest, embedding itself within the material body of the sand through the inscription of the slogan “100% Aussie Pride.” These embodied significations construct whiteness as an inalienable property, the purity of which is always potentially at threat from racialized others through contamination and dispossession.32 At Cronulla, the white male body performatively repossessed the beach through anti-Arabic resentment, thus mimetically reproducing the racialized colonial violence enacted to dispossess Indigenous people.

In response to the events of 2005, one of Australia’s leading Indigenous artists, Vernon Ah Kee of the Kuku Yalandji, Waanji, Yidinji, and Gugu Yimithirr peoples, challenged Australian popular culture, racism, and representations of Indigeneity in his exhibit at the Venice Biennale in 2009. The Cronulla riots provided a context for Ah Kee’s art installation entitled Cant Chant, which offers its audience an Aboriginal man’s rendering of the beach, drawing on, but in opposition to, its signification within popular culture as a site of everyday white male performativity and representations of “Australian-ness.” Common ownership of the beach looms large in the Australian imagination, but as violent attacks on Cronulla Beach demonstrate, not everyone shares the same proprietary rights within that space. His work frames the beach as an important site for the defense and assumption of territorial sovereignty. It is the place where invaders have landed, and on Australia Day it is reenacted as the place where in 1788 Captain Arthur Phillip planted a flag in the name of some faraway sovereign to signify white possession.

Ah Kee plays with the idea that iconic beaches such as Bondi and Cronulla are white possessions, public spaces perceived within the white Australian imaginary as being urban and natural, civilized and primitive, spiritual and physical. He is acutely aware that the beach is a place where nature and culture become reconciled through the performativity of white male bodies such as lifesavers and surfers. Ah Kee undoes this reconciliation by disrupting the beach as a site of fantasy production where carnival and nature synergize as prehistory in the dialectical image of modernity. He challenges white possession of the beach by making visible the omnipresence of Indigenous sovereignty through the performativity of the Indigenous male body. In this way he brings forth the sovereign body of the Indigenous male into modernity, displacing the white male body on the beach.

The beach is Indigenous land and evokes different memories. As the viewer enters Ah Kee’s installation, surfboards hang in the middle of the room, and painted Yadinji shields with markings on one side in red, yellow, and black, the colors of the Indigenous flag, signify our sovereignty and resistance. On the other side of the surfboards, the eyes of Aboriginal male warriors gaze silently at their audience, bearing witness to their uninvited presence. The gaze of Ah Kee’s grandfather looks to the east, surveying the coastline in anticipation of invaders. The silent gaze is broken by the text on the walls:

Ah Kee the sovereign warrior speaks his truth. We grew here you flew here, we are the first people, we have to tolerate you, we are not your other, you are dangerous people and your duty is to accept the truth for you will be constantly reminded of your wrong doing by our presence. Aboriginal people are not hybrids and will not comply with what you think you have made us become.

Moving out of the first room, the viewer enters another, where a video clip intermittently echoes the sounds of the land and water with the song “Stompin’ Ground,” sung by Warumpi, an Indigenous band. The song’s message to its audience: if you want to know this country and if you want to change your ways, you need to go to the stomping ground for ceremonial business. Ah Kee performatively reiterates Indigenous sovereignty through the use of this song, which offers its white audience a way to belong to this country that is outside the logic of capital and patriarchal white sovereignty. Here Ah Kee also plays with irony because the “Stomp” was the surfers’ dance made famous by Little Pattie, one of Australia’s original surfie-chick icons. And white Australian youths have continued to stomp all over the beach as shown in video clips for Australian rock bands such as INXS and Midnight Oil, in soap operas such as Home and Away, and in the movie Puberty Blues.33 Ah Kee’s juxtaposition of the Warumpi band’s call to dance for the land and the white performative dancing on the land reiterates Indigenous Australia’s challenge to white possessive performances and their grounding in patriarchal white sovereignty.

At the entrance to the second room, Ah Kee invites his audience to bear witness to a seeming anomaly: Aboriginal surfers at the beach. The video shows the Aboriginal surfers walking around the Gold Coast, surveying the beach before entering it with their shield surfboards. The surprised look of a white male gaze is captured on film. This surprise suggests that to the white male beachgoer, Aboriginal surfers are out of place; they are not white in need of a tan, they belong in the landscape in the middle of Australia, not on the beach. Ah Kee plays on this anomaly by taking his audience to the landscape away from the beach, where death is signified by two cemeteries. Suddenly guns are fired repeatedly at two white surfboards encased with barbed wire, one hanging from a tree, the other tied to a rock. The barbed wire evokes the fencing off of the land against Indigenous sovereignty and the wire that was used in the trenches at Gallipoli, both signifying death and destruction. Here Ah Kee brings forth repressed memories of the violence of massacres, incarceration, and dispossession hidden in landscape that is far away from the beach. There is silence as the clip moves back to the beach, where memories of the violence inflicted on Aboriginal people are repressed by its iconic status within the Australian imagination. Suddenly a lone Indigenous surfer appears on his shield surfboard gracefully moving through the water, displaying his skill as he takes command of the waves. He is not out of place. He embodies the resilience of Indigenous sovereignty disrupting the iconography of the beach that represents all that is Australian within white popular culture. Like a stingray barb piercing the heart of white Australia, Ah Kee’s masterful use of irony and anomaly reinserts the Indigenous male body at the beach, displacing the white male body as the embodiment of possession 239 years after Captain Cook’s originary possessive performance.

Vernon Ah Kee, cantchant, 2007 (still). Three-channel video. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane.

Conclusion

The production of the beach as a white possession is both fantasy and reality within the Australian imagination and is tied to a beach culture encompassing pleasure, leisure, and national pride that developed during modernity through the embodied performance of white masculinity. As a border, the beach is constituted by epistemological, ontological, and axiological violence, whereby the nation’s past and present treatment of Indigenous people becomes invisible and negated through performative acts of possession that ontologically and socially ground white male bodies. White possession becomes normalized and regulated within society through socially sanctioned embodied performative acts of Australian beach culture. The reiterative nature of these performances is required because within this borderland the omnipresence of Indigenous sovereignty ontologically disturbs patriarchal white sovereignty’s possession and its originary violence. Ah Kee’s work powerfully demonstrates the resilience of Indigenous sovereignty and its ability to disturb ontologically the performativity of white possession. Continuing the tradition of his ancestors, it is appropriate in the twenty-first century that the silence of the beach becomes the object of Vernon Ah Kee’s sovereign artistic warrior-ship.

Regina Ganter, Mixed Relations: Asian-Aboriginal Contact in North Australia (University of Western Australia Press, 2006).

Michael Taussig, “The Beach (A Fantasy),” Critical Inquiry 26 (Winter 2000): 249–77; 258.

Aileen Moreton-Robinson and Fiona Nicoll, “We Shall Fight Them on the Beaches: Protesting Cultures of White Possession,” Journal of Australian Studies 30, no. 89 (December 2007): 151–62.

Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (Routledge, 1993).

Richard Dyer, White (Routledge, 1997).

Keith Vincent Smith, “Voices on the Beach,” in Lines in the Sand: Botany Bay Stories from 1770, ed. Ace Bourke (Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre, 2008), 13–22; 13.

Aileen Moreton-Robinson, “White Possession: The Legacy of Cook’s Choice,” in Imagined Australia: Reflections Around the Reciprocal Construction of Identity Between Australia and Europe (Peter Lang, 2009).

Butler, Bodies That Matter.

Damien Riggs and Martha Augoustinos, “The Psychic Life of Colonial Power: Racialised Subjectivities, Bodies, and Methods,” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 15, no. 6 (2005): 461–77; 471.

Caroline Ford, “Gazing, Strolling, Falling in Love: Culture and Nature on the Beach in Nineteenth Century Sydney,” History Australia 3, no. 1 (2006): 8.1–8.14; 8.3.

Ibid., 8.2.

Cameron White, “Representing the Nation: Australian Masculinity on the Beach at Cronulla,” in Everyday Multiculturalism, Conference Proceedings, Macquarie University, September 28–29, 2006 (Centre for Research on Social Inclusion, Macquarie University, 2007), 2.

H. C. Coombs, Aboriginal Autonomy: Issues and Strategies (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 71.

Douglas Booth, “Ambiguities in Pleasure and Discipline: The Development of Competitive Surfing,” Journal of Sport History 22, no. 3 (Fall 1995): 189–206; 190.

Sara Ahmed, Differences That Matter: Feminist Theory and Postmodernism (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 116.

Farid Farid, “Terror at the Beach: Arab Bodies and the Somatic Violence of White Cartographic Anxiety in Australia and Palestine/Israel,” Social Semiotics 19, no. 1 (2009): 59–78; 66.

“Yamba Call to Oars,” Daily Examiner, January 16, 2010.

Fiona Nicoll, From Diggers to Drag Queens: Reconfigurations of National Identity (Pluto Press, 2001).

White, “Representing the Nation,” 5.

Ibid., 6.

Booth, “Ambiguities in Pleasure and Discipline,” 190.

Ibid.

I. Helekunihi Walker, “Terrorism or Native Protest? The Hui ‘O He’e Nalu and Hawaiian Resistance to Colonialism,” Pacific Historical Review 74, no. 4 (2005): 575–601; 576.

See →.

Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Talkin’ Up to the White Woman: Indigenous Women and Feminism (University of Queensland Press, 2000).

Aileen Moreton-Robinson, “The House That Jack Built: Britishness and White Possession,” ACRAWSA e-journal 1 (2005).

Sue Ebury, Weary: The Life of Sir Edward Dunlop (Penguin Books, 1994).

Nicoll, From Diggers to Drag Queens, 29.

Moreton-Robinson, “The House That Jack Built.”

The Weekend Australian, February 26–27, 2005, 19.

Moreton-Robinson and Nicoll, “We Shall Fight Them on the Beaches.”

Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness as Property (1993),” in Black on White: Black Writers on What It Means to Be White, ed. David Roediger (Shocken Books, 1998).

Moreton-Robinson and Nicoll, “We Shall Fight Them on the Beaches.”

Subject

Reprinted with permission from Aileen Moreton-Robinson, The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty (University of Minnesota Press, 2015).