Russian cosmism—a trend in Russian philosophical thought of the second half of the nineteenth through the first half of the twentieth century—is one of the original variations of international cosmism. Its founder is Nikolai Fedorov, the author of The Philosophy of the Common Task. We can distinguish two of its main branches: a natural-scientific (Sergei Podolinsky, Nikolai Umov, Vladimir Vernadsky, Alexander Chizhevsky, N. G. Holodnyi, V. F. Kuprevich) and a religious-philosophical one. The latter includes not only Fedorov’s followers of the 1920s through the 1930s (Alexander Gorsky, Nikolai Setnitsky, and Valerian Muravyov), but also such major figures of Russian religious philosophy as Vladimir Solovyov, Sergei Bulgakov, Nikolai Berdyaev, and Pavel Florensky. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s cosmist philosophy and the “Vsemir” (Allworld) teachings of Alexander Sukhovo-Kobylin occupy a special place in the cosmist “family of ideas.”

Russian cosmism regards the interrelations between humankind and cosmos, microcosm, and macrocosm in a projective, active-creative sense. Humankind, according to this school of thought, is not just a spectator of the world, of earth’s vast expanse, of the majestic panorama of the starry sky, but also an active participant in the process of the world’s creation. A human is a creature on whom the fates of history and the final destinies of the universe alike depend. As Fedorov puts it, “Born by the tiny earth, a spectator of the boundless space, a spectator of the different worlds which are part of this space, must become their resident and master.”1

Theophanes the Greek’s fresco in the Church of the Transfiguration of the Savior on Ilyina street in Novgorod, 1378.

The cosmist aesthetic is closely bound with the theme of immortality. By pronouncing that “life is good, and death is evil,”2 that “immortal life is the true good, while death is the true evil,”3 Fedorov not only unites the category of good with the category of life, as well as ethics with ontology; he also interprets life as striving to ascend towards immortality, as participating in what Vladimir Solovyov, in one of his later articles, would call “a cosmic growth.” Fedorov invites us to “imagine the great joy of those who are resurrecting and those who are resurrected, a joy in which goodness, truth, and beauty are present in their full unity and perfection.”4 In this way Fedorov completes the trinomial of Alexander Baumgarten, the famous father of aesthetics. Baumgarten’s “truth”—“goodness”—“beauty” in Fedorov are complemented with a fourth category of “perfection.” Тhe same image of elevating being to a perfect state is found in Pavel Florensky:

The image of Sophia is Mother, Bride, and Wife of the image of Christ-Man. She is his equal, she awaits his care, caress and impregnation by spirit. Man-Husband ought to love the World-Wife, to be united with her, to cultivate her and to tend to her, to rule her and to direct her toward enlightenment and spirituality, to guide her elemental might and chaotic drives towards creativity, so that her creaturely nature may give birth to the primordial cosmos.5

Man’s relation to the world here appears as an aesthetic relation. This is not a passive “contemplation” of the beauty of being, but a cosmicization of the world: a creative act that consists of overcoming the dark, chaotic elements of nature—that shapeless monstrosity—which is a trait of its “fallen” state and which manifests itself in death, decomposition, devouring, displacement.

Nikolai Fedorov and Sergei Bulgakov held that the task of human creativity is to assist in “restoring the world to the splendor of incorruptibility it had before the Fall.”6 Vladimir Solovyov, Nikolai Berdyaev, Nikolai Setnitsky, and Valerian Muravyov were developing the idea of “continuous creation.” This idea became a religious-philosophical counterpart to the notion of active, directed evolution that was developed by cosmism of the natural-scientific bent. The act of divine creation here exceeds the first seven days and extends to the entire process of the world’s development, from the initial Edenic state in which the world is imbued with the potentiality for a benevolent maturation and strives for an absolute (its ideal program, so to speak), to the transfiguration of the entire universe into a Divine Kingdom. History is understood as the “eighth day of creation,” in which the active role is given to humanknind.

Beauty in the philosophy of cosmism is not an aesthetic category, but an ontological one. Beauty is a measure of creation’s perfection, its spirituality, goodness, and fullness. It is one of the crucial characteristics of the divine plan of being. Fedorov, Solovyov, Bulgakov, and Florensky all agreed on that. Solovyov defines beauty as a complete union between idea and form, between spirit and flesh. Beauty for Solovyov is “spiritual flesh” that restores and gives new life to the classical ideal of kalokagathia. He paints the development of the world as a “gradual and persistent” process of the embodiment of the divine spark in chaotic and formless matter: first in the nonorganic sphere (water, rocks, minerals), then in plants and animals (a process that is accompanied by unavoidable sufferings and the dead ends of “unfinished sketches of unsuccessful creations”), and, finally, in humankind, who becomes an absolute form for being and spirit.7 The world’s ascent toward perfection from now on should move along the line from humanity to divine-humanity and from matter to divine-matter, from the “cruel life” of postlapsarian nature, with its “double impenetrability” of things and phenomena (they cannot simultaneously occupy the same point in space and supersede each other in time), toward the state of the “absolute unity” and “universal syzygy.”

The theory about the ontology of beauty, about its being “as much of an absolute foundation of the world as Logos,”8 was comprehensively developed in the sophiology of Sergei Bulgakov. In Philosophy of Economy: The World as Household (1912) he defines Sophia (Divine Wisdom) as a composite ideal image of the world and humankind—an image that is eternally contained in God, in beauty, in glory, and in imperishability. Divine wisdom “soars” over the world, illuminating it with divine light and connecting it with a living thread to God.9 It doesn’t abandon the created world even after the original sin and continues to guide humankind and nature towards the restoration of lost unity. Bulgakov holds that art is most receptive to the “sophiological foundation of the world.” By creating in beauty, by aiming to realize magnificent images, the artist becomes a conduit for the light of divine wisdom and illuminates matter through it, “revealing creation in the light of transfiguration.”10

Cosmists of the natural-scientific orientation also tend to regard beauty as a kind of entelechy of the world, as an ideal that imparts a necessary initial impulse to the cosmogonic process and then continues to sustain it, keeping it on the necessary course. Nikolai Umov, a physicist and a philosopher, defined beauty as a visible manifestation of a fundamental property of the living matter that he called harmony (stroinost’). According to Umov, a human being is the highest embodiment of such harmony. Acutely sensitive to every instance of disharmony, striving to increase harmony in all spheres of life, humankind imparts the name “beauty” to all instances of harmony. A sense of beauty is a regulator of human behavior in the world; it guides people towards the realization of their evolutionary purpose: to conquer chaos, death, and entropy, to be cosmisators of a boundless universe, to become true “apostles of light.”11

Fedorov, who gave a comprehensive description of cosmist aesthetics in The Philosophy of the Common Task, strove to understand the ultimate problems and aims of art by turning to its origins, to primordial antiquity, to the dawn of humankind. He was convinced: the principle impetus to what we call art was given by the awareness of mortality, by the feeling of loss and longing for the deceased. Art, according to Fedorov, is born by the grave; the creative impulse begins with grief. Through physical necessity, humans who bury their dead give them new life in the shape of monuments, and aim to recreate them through painting or sculpture—to restore them to existence, if only through representation. Fedorov emphasizes that art, in its origins, is an attempt at “artificial resurrection”: by following a genuine heartfelt emotion, it restores what through “a physical necessity” was buried in the ground.

The protest against mortality, the hunger for immortality and resurrection, bestowed an initial impulse to human creativity. Fedorov remarks that it was out of a feeling of loss, out of protest against death that the first artistic monuments appeared. They were intended to recreate the image of the deceased through painting or sculpture, to restore his or her likeness at least as a representation.

Among the diverse, always aphoristic and figurative definitions that Fedorov gives to art, there is the following: art as “a countermeasure against the Fall.” Fedorov illustrates this definition with the example of architecture. Its creations are extended vertically, visibly demonstrating defiance of the law of gravity. This law embodies for Fedorov the force of nature’s necessity, which leads all organic and inorganic bodies towards decay, sin, and death. Architecture gathers and artistically organizes natural matter and creates out of it a new, perfect, and harmonious world. Architectural space is ruled by different laws—the laws developed and applied by humankind itself.

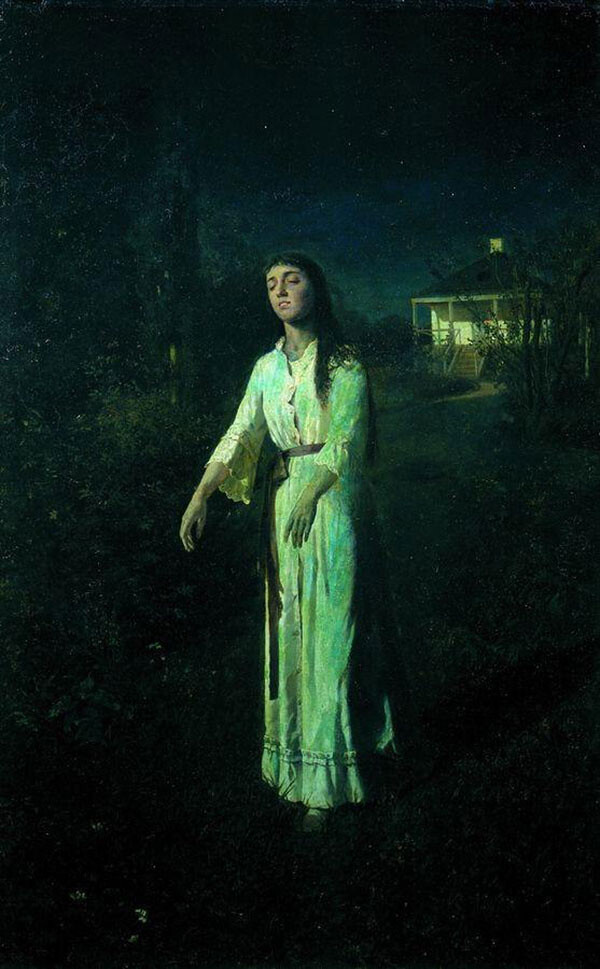

Ivan Kramskoy, Somnambulant (Сомнамбула), 1871. Oil on canvas. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In this way, the aesthetics of cosmism emphasize a projective, transformative property of art. Art realizes in a small-scale, preliminary, and “experimental” manner the principle of regulation that, Fedorov was convinced, should become the foundation for human activity in the world. This principle is radically opposed to the consumerist attitude toward the world, to the exploitation of earth’s resources, which distorts nature rather than bringing harmony into it. Present-day art for Fedorov should be an experimental antecedent to the future universal creativity that will truly transform life. We find a similar thought in Vladimir Solovyov. He stresses the prefigurative quality of artistic reality: it has the power to reveal the image of the future world, a world in which the “dark force” currently ruling “material reality” would be overcome. Art is called to become a “prophecy” about the future Heavenly Kingdom, a “transitional link between the beauty of nature and the beauty of the future life.”12

The transformative, regulatory property of art is most distinct in “sacred” religious art. Here it adopts the necessary power and directional force and is wholly oriented toward the higher goal. Fedorov writes a lot about the symbolism of the temple. It embodies a religious and artistic model for the transfiguration of the universe; it is “a project of the world as it must be, that is, a project of the new earth and the new sky, filled with a force that is neither destructive nor mortifying, but all-constructive and life-building.”13 Fedorov regards the liturgy that takes place within its walls—the holy communion of believers, united in a collective prayer for the dead—as a model for the future liturgy that will take place outside of church, for the universal collective task of transfigured humanity that will restore life to those “from whom it received life.”14

Using the example of art to demonstrate the principle of regulation—the mature, truly creative attitude toward and ability to act in the world—Fedorov points out art’s double orientation. It is directed not only outside, toward surrounding life, but also inward, toward the nature of humankind itself.

Humans, for Fedorov, are not only creative but also self-creating creatures. And “the first act” of his self-invention is to adopt a vertical position.15 Thus, long before the erection of monuments, temples, and architectural constructions, humankind marked its arrival into the world by a radical opposition to the force of gravity—a force that aims to drive every creature into prostration, that does not allow anyone to rise above prescribed limitations—and declared itself above any animal fate. Religious, devout striving toward the sky, toward the universe and God, became humankind’s first artistic impulse and act. This artistic act was not aimed at creating a second reality; it was not an attempt at symbolic resurrection. Instead, it was an act of self- and life-creation: “In assuming a vertical position, as with every act of self-overcoming, a man or the son of man becomes an artist and an artwork—he becomes a temple … This is the aesthetic interpretation of life and creation. Moreover, not only is it aesthetic, it is also sacred. Our life is an act of aesthetic creativity.”16

The religious act of rebellion, of the overcoming of the self, opens a long history of human artistic self-creation. Its apogee, according to Fedorov, should be a complete, not only moral, but also physical transformation of a person, the acquisition of a new and immortal nature (“a spiritual body,” to use St. Paul’s definition). This for Fedorov is the most important part of Christian activity in the world; it fully reveals the divine plan for humankind to become a creator, a being who is good, conscious, and free. (Fedorov repeatedly emphasizes that “only a self-created creature may be free.”)17 This is the highest form of art; this is the art of a divine transfigured humanity, or, as Fedorov writes, of a “theoanthropourgical” humanity. This art “consists in God creating man through man himself.”18

Humans, therefore, are not only the subjects of artistic creativity, but also objects to which artistic energies are applied. Already in the 1920s this thesis would receive special attention from Vasily Chekrygin, a Russian avant-garde artist who was close in spirit to the Russian cosmists. Chekrygin is the author of “Resurrection: A Migration of People into Space,” a series of graphic works, sketches for the future frescoes of the Cathedral-Museum of the Common Task. Chekrygin, like Fedorov, places humankind at the center of the new synthetic art—universal in its intended scope and scale—the purpose of which would be to “build Paradise.”19 A human being for Chekrygin is both a subject and an object of art. In Chekrygin’s terms, he is a creation and, simultaneously, a creator. He is an embodiment of the “highest synthesis of the living arts,” “a living painting, sculpture, architecture, and music.”20 He is a living, albeit so far incomplete and imperfect, artistic creation, who is destined to overcome himself and to become a regulator and a creator of his own still mortal nature. In the end, humankind is bound to become a builder and helmsman of the entirety of creation.

Achieving “complete symphonicity,” immortality, restoration from death—all these are the composite parts of the “art of reality.” According to Fedorov, the art of reality should replace the then-current “art of representations,” which Fedorov reduced to something capable only of creating a “second,” artistic “reality.” Such art of representations can overcome entropy and death only on the scale of an “immortal masterpiece.” It freezes time not in the real duration of being and history, but in the space of a painting. It resurrects the likeness of the deceased not in the living flesh, but only in language, sculpture, or on a canvas. To remain on the level of the creativity of “dead representations” would mean to castrate art, to hobble it, to profane its true task, to turn it into an aesthetic folly, into a mere pastime that does not commit anyone to anything. However, if we deeply ponder a myth that contains all of humanity’s innermost desires—for instance, the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, so beloved by the artists of the modernist epoch—then it will become clear that the creation of this second reality, no matter how perfect it may be, no matter how much aesthetic admiration it might elicit, is not the genuine goal of art. Its goal is life itself—a perfect life, built according to the laws of beauty and harmony, a transfigured and incorruptible life not wounded by the sting of death.

Some time later, while analyzing the essence of a creative act and the meaning of inspiration, Alexander Gorsky, a philosopher-cosmist, would emphasize that a creator of an artistic image is striving to project and to fix in reality a vision and intuition of a “new perfect nature,” which is “better and fuller than the one we are chained to,” which doesn’t satisfy us.21 And we mustn’t stop with anticipations and intuitions alone. We must be reborn, we must shroud ourselves with this new image and rebuild our mortal body in accordance with it.

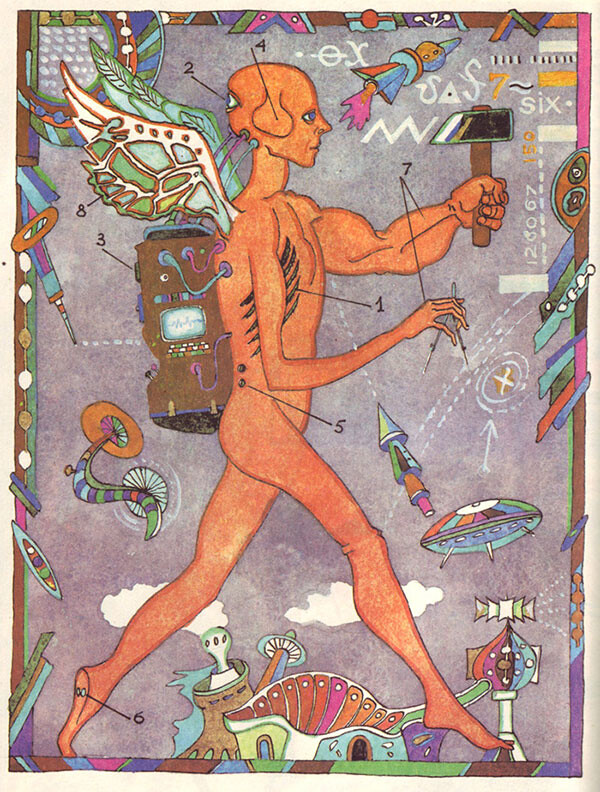

A Russian textbook for elementary school children titled The Miracle of Life (1992).

Thus, the theme of art as life-creation enters the aesthetics of cosmism. Its sphere is no longer the world of imagination and fantasy, but the entire universe, all “celestial and now soulless starry worlds, which regard us coldly and almost sorrowfully.”22 Cosmists believe that art should “embody the absolute ideal not in imagination alone, but in reality. It must spiritualize and transform our real life.”23

In his Supramoralism, Fedorov gives the following picture of the cosmic art of the future: the “sons of man” having, at last, reached “the age of Christ,” having mastered the laws of the structure and function of matter, having learned to overcome the forces of decay, will transform these worlds, will unite them “into an artistic whole, into an artwork, the collective composite author of which will be, in the likeness of the Holy Trinity, the entirety of humankind as the composite of all resurrected and recreated generations.”24 Art would then truly resurrect and restore the image of the deceased—not on wood, stone, or canvas, but already in reality, in the indestructibility of the union of spirit, soul, and the physical body. The human body itself—now imperfect, not self-sufficient, and mortal in principle—will be the new object of art.

The main thesis of Russian cosmism is the following: the laws of artistic creativity, which produce the world of perfect, beautiful forms, should become the laws of reality itself; they must actively create life. Fedorov writes that “aesthetics is a science about the restoration of all sentient beings who used to populate the tiny earth (this drop that has reflected itself in the entire universe and that has reflected the whole of the universe in itself), so that they can spiritualize (and govern) all enormous celestial worlds, which are now devoid of rational beings.”25

However, this enormous task cannot be accomplished by means of a present-day art that is nothing but a plaything. Achieving this task would require overcoming the limitations of art, creating art with a new kind of integrity and capacity for harmonious and synthetic activity. Such an art would be simultaneously world-building and expressive; it would influence reality at the very same time as it dresses it up in wonderful forms.

The most important stage on art’s path towards achieving a new mature state is its close collaboration with scientific thought. Science, unlike art with its whimsical fantasy, does not produce ideal images. Instead science studies the properties of the real world, deeply examines reality, while organizing and systematizing humanity’s labor according to the laws that it has uncovered. Fedorov asserts that without the fastidious labor of learning that science takes upon itself, the artistic management of the world would be impossible.

However, to get fully united with art, science itself must be radically broadened and morally transformed. It must advance beyond isolated tests and experiments conducted in the confines of a laboratory and instead begin an exploration on a new truly universal scale. It must work not in the service of mutual destruction, not in the name of the ideals of the society of consumption, not for the profit of a select few, but for the salvation and regulation of life. It will befall science to chart the paths toward realizing the project of the perfect world that is revealed in the highest instances of art.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Fedorov’s followers, such as Gorsky, Setnitsky, and Muravyov, continued to develop the idea of synthesizing science and art, knowledge and creativity. Such a synthesis felt especially relevant to the people of that epoch, who experienced world and civil wars, postrevolutionary devastation, and hunger. All of these thinkers posed the question of whether art and science had the right to focus exclusively on theoretical and aesthetic activity at the time when humanity faced global, planetary, and cosmic problems and tasks.

While emphasizing idealized collaboration between science and art, cosmists of the 1920s also wished to add labor and religion to this equation. Religion rules, for it is the creativity of the ideal. Art that is founded on an ideal organizes science effectively and dynamically, while “coordinating, systematizing, and guiding all the analytical, research, and experimental activity of humankind.” Science, in turn, imparts real organization to “all human labor” and guides it toward the “transfiguration and humanization of nature,” resurrection, and life-creation.26

The philosophical and aesthetic views of Valerian Muravyov developed in the context of life-creationist aesthetics. He conceptualized future culture as a cumulative, synthetic activity, the aim of which was to conquer space and time and to establish the “cosmocracy and pantocracy” of the human kind. Muravyov believed that overcoming the existing divide between the types of activities which enact a “symbolic” transformation of reality (literature, painting, music, architecture), and those “which change the world around us in actuality and not just in thought or imagination,” to be the first step toward this culture. Among the latter activities he counted “economy, industry, agriculture, technology, medicine, eugenics, practical biology, pedagogy,” etc. Muravyov was convinced that both symbolic and practical cultures must be united and organized within a unified plan of cosmic construction.27

At the same time, Muravyov particularly emphasized those directions of applied science which deal with “the question of the biological enhancement of man,” and with “the transformation and rejuvenation” of his physical nature. In the future, Muravyov argued, it would be these trends that would give rise to “a special kind of art of enhanced anthropology—anthropotechnology or even anthropourgy.”28 Such an art would be capable of putting to active use the accomplishments of medicine, chemistry, and genetics in order to creatively transform people‘s physical constitutions.

Perhaps, in the future, new constitutions would be invented, which would be absolutely free from the negative aspects of organic matter today. New bodies would be created, which would possess far greater plasticity, might, agility. They would move at great speed without any external devices, they would sustain themselves through photosynthesis and would not be affected by the laws of gravity to the extent that they affect physical bodies today. At the same time, they would think, feel, sense, and be able to act remotely.29

In his daring dream, Muravyov even anticipated the possibility of humanity cultivating a new kind of life, ushering into the world sentient, thinking creatures not through “unconscious birth,” but through a collective effort of “symphonic” creativity: “Just as musicians in an orchestra attune and harmonize with each other and just as symphonic unity gradually emerges through a combination of inspiration, temperament, and technique, so should the creators of a new man unite in a single harmonious pursuit of the new human ideal.”30

The aesthetics of cosmism, with its demands for the integrity of art and the synthesis of science and art in the name of the common task, were significantly different from the trends of the Russian avant-garde, which also insisted on the artistic transformation of life. Avant-garde artists envisioned this transformation happening either along an artistic—and only an artistic—path, or along a scientific and technological path. They likened the work of an artist to that of an engineer or designer, and art to production. Alexander Gorsky, while criticizing symbolism’s theurgic utopia, was right to point out the fantastic and utopian nature of the desire to surpass reality through individual, instantaneous, Promethean drives, to overcome the curse of illness through art alone. At the same time, Russian cosmists emphasized that the problem of “life and art” could not be resolved merely by calling for the unity of art and production. For art’s most important and specific quality—its transformation and immortalization of reality, its ability to represent ideals of world and humankind in an image—disappears once art is reduced to mere craft, to the manufacturing of things. Vasily Chekrygin understood this well. By defending, in a discussion with fellow artists, the nature of the creative act, he drew attention to yet another particularity of art: unlike technology, it does not build or construct, but rather constantly gives birth to its creations. Art is not mechanistic, but organic. Masterpieces of engineering genius—the most sophisticated, precise instruments and machines, monumental constructions, and clever devices—astonish us with their “ugly, unnatural constructiveness.” “Technical construction (of contemporary instrumental weaponized technology) does not carry within itself the traces of artistic construction”—a construction that, while embodying in itself new qualities previously not found in nature, still preserves natural plasticity, elegance, and beauty.31

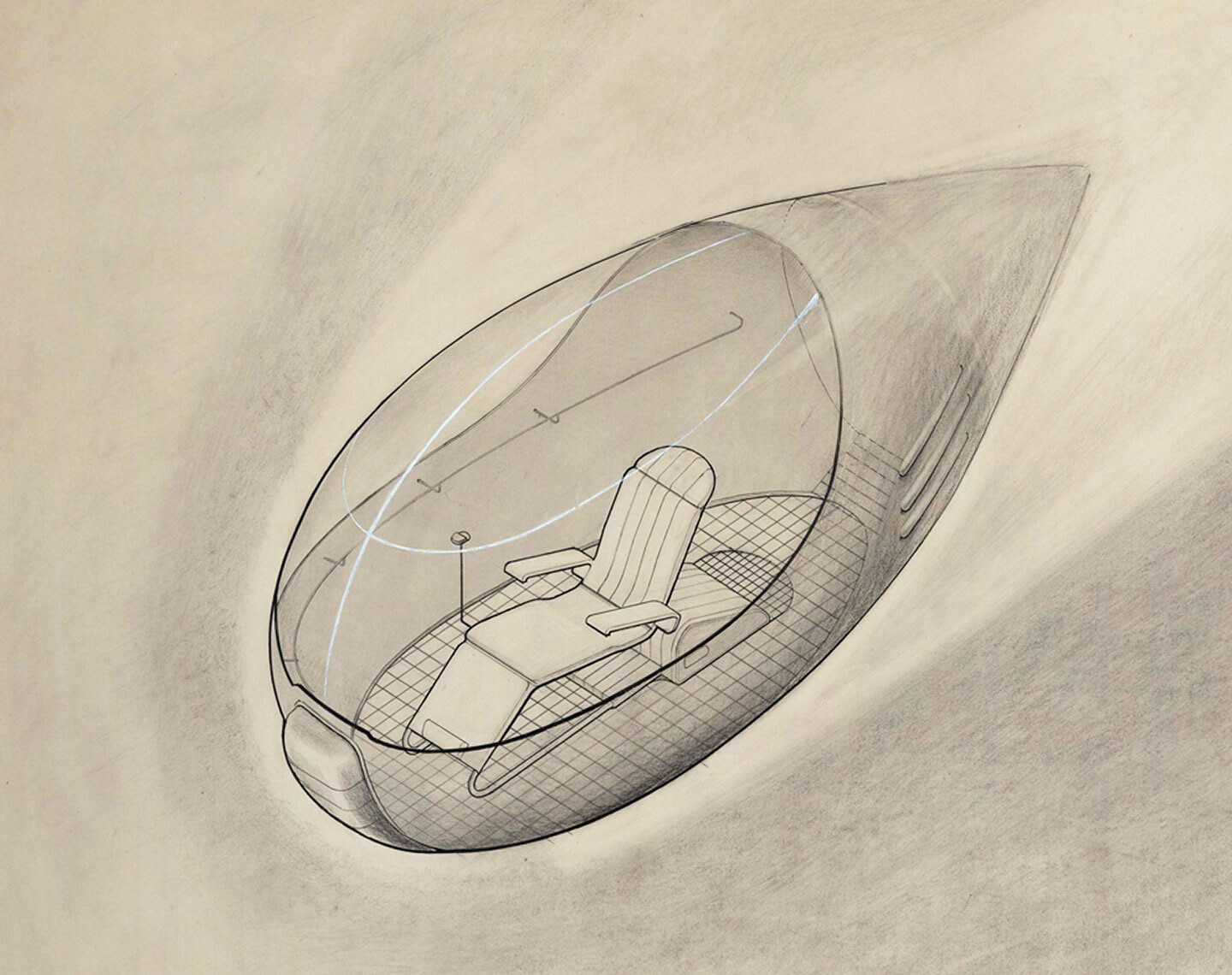

Deviant art user Anestazy’s illustration in honor of Tsiolkovskiy The Dreamer from Kalugaby (date unknown).

For this reason, cosmist thinkers founded the Organizatsya mirovozdeistivya (Organization of world-transformation), which was meant to encompass all types of creative human activity, all spheres of theoretical and practical application—on the creative principle found in art. Art opens before humanity an opportunity to move away from the present instrumental, technical progress, which acts upon nature only from outside, by use of mechanisms and machines, to a new, mature type of progress that would be organic, that would transform and spiritualize the world through a living, non-mediated touch.

In conjunction with this last point, it is impossible not to mention Alexander Gorsky’s ideas, expressed in his tractatus on aesthetics, entitled “An enormous sketch” (1924) and further developed in his letters from the late 1930s and early 1940s. By turning toward the study of the artistic process and by drawing on concepts from psychoanalysis, as well as from various spheres of art (primarily music and literature), Gorsky came to the conclusion that a profound connection and psycho-physiological proximity exists between creative and erotic arousal. Gorsky described the particular autoeroticism of an artist. This autoeroticism is nourished by a deep-seated striving for perfection and integrity. It carries within itself “a dream of a new body,” of harmony, beauty, and spirituality. The work of artistic imagination is directed by an “erotic admiration of one’s own body in its totality,” by a desire “to see a different … more attractive image of oneself, an image that would contain the best elements of the earlier appearance now supplemented by the new and previously missing ones.”32

The eros of enhancement, of transfiguration and elevation, this passionate striving toward an ideal, is present within the artistic drive on an unconscious, profoundly intuitive level. However, its role in art is tremendous. It is this very eros of enhancement that is the source of that mysterious “lyrical excitement” which is so different from “everyday” arousal in its purposefulness and regulatory and constructive force. Gorsky believed that a new type of eroticism is born through transformations stimulated by this excitement. This eroticism is magnetic and dispersed. Arousal isn’t limited to the sexual sphere, but spreads throughout the entire organism. It forms around itself a powerful, energetically charged atmosphere, a “magnetic force field” of sorts. This erotic cloud surrounding the body gives rise to a feeling of wholeness, completion, and joyful omnipotence, and soon the artist’s entire being is alight with a striving for creativity. Through this creativity, life-transmitting energy finds release.

Eros in art constructs not only bodies; it also constructs the world. It is directed toward the harmonization of the spiritual and physical appearances of humankind as well as its natural and cosmic environment. The creative act opens, “for an organism, the possibility to limitlessly expand the sphere of its vibrations by freely emanating into space and boldly shaping and transforming the finest structural nets of the surrounding matter by its waves.”33 Gorsky admits that this possibility is still only embryonic at the (then-)current stage of art, but stresses that its evolution is advancing steadily from an indirect and mechanical to an immediate, organic, and “miraculous” influence: “so that the creative act … will resemble the birth of a new living being,” so that artistic images will appear on nature’s canvas independently, without the assistance of hands and instruments, so that diverse natural elements and forces will compose a harmonious whole under the influence of smooth streams of energy directed by the creative will.34

Inspired by Plato’s teachings on the cosmogenic force of eros, Fedorov’s idea of “positive chastity,” and the ideas expressed in Vladimir Solovyov’s The Meaning of Love, Gorsky places before art the task of regulating erotic energy. Until now, this energy has either been squandered in sexual acts and reproducing through childbirth short-lived mortal life, or in searching for sublimation in artistic creativity, which can create only dead albeit beautiful things. Gorsky, on the other hand, demands that an unconscious, chaotically boiling sexual energy be introduced into consciousness. His reasoning is partially based in the teachings of yoga. However, his main inspiration (which he boldly transcends) is the experience of the Christian wanderers. Gorsky believes that self-control, the labor of attention, sobriety, and spiritual concentration—all those elements which are at the core of hesychastic “intelligent action”—shouldn’t block erotic centers, but, on the contrary, must illuminate them with the light gained through prayer. It must direct the mighty forces of eros toward constructive, resurrective, and “body-building” goals.

The metamorphosis of erotic energy, according to Gorsky, is one of the main stages that humanity must pass through to achieve integral, perfect nature—“a new body,” in which nothing unconscious or blind remains, but everything is spiritualized and subjugated to reason and moral sensibility. This erotic energy is, at the same time, a necessary condition for art’s transition from the stage of anticipation and prophecy towards actual comprehensive life-creation. By achieving a quality of full “organicism” (Fedorov’s term), by mastering all of its living forces and energies, humanity as a whole, and each person individually, will be able to multiply life in reality and not just symbolically, to reproduce it “by means different from those of unconscious animality.”35

The philosophy of cosmism, in its theoretical ideas and views on art, had a significant impact on the culture—and in particular Russian culture—of the twentieth century. The influence of Fedorov’s speculations about resurrection, Tsiolkovsky’s cosmist ideas, and Vernadsky’s notion of the noosphere can be traced in the works of Valery Briusov and Vladimir Mayakovsky, Nikolai Kliuev and Sergei Yesenin, Velemir Khlebnikov and Nikolai Zabolotsky, the poets of the “Smithy” and “cosmist” groups, the biocosmists, Mikhail Prishvin and Maxim Gorky, Andrei Platonov and Boris Pasternak, Chinghiz Aimatov, Anatoli Kim, and others. The aesthetics of Russian cosmism infused the artistic strivings of the Russian avant-garde (Andrei Belyi, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Kazimir Malevich, Vasily Chekrygin, Pavel Filonov, and others). However, this is a topic for a separate conversation.

N. F. Fedorov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), vol. 4, t.T.2 (M., 1995), 243.

Ibid., 136.

Fedorov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), vol. 4, t.T.1 (M., 1995), 390.

Ibid., 136.

P. A. Florensky, Sochinenya (Works), vol. 4, t. T. 3(1) (M., 2000), 440.

Fedorov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), vol. 4, t.T.1 (M., 1995), 401.

V. S. Solovyov, Sochinenya (Works), vol. 2, t.T.2 (M., 1988), 358 and others.

S. N. Bulgakov, Svet nevecherny: Sozertsanya i umozrenya (The light of the unknown: Contemplation and speculation) (M., 1994), 219.

S. N. Bulgakov, Filosofya hoziaistva; Bulgakov, Sochinenya (Works), vol. 2, t.T.1 (M., 1993), 158.

Bulgakov, Svet nevecherny (The light of the unknown), 306.

N. A. Umov, Evolutsya fizicheskih nauk i ee ideinoe znachenye (The evolution of the physical sciences and their ideological significance); Umov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), T.3. (M., 1916), 517.

Solovyov, Sochinenya (Works), vol. 2, t.T.2, 398.

Fedorov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), vol. 4, t.T.1, 159.

Fedorov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), vol. 4, t.T.1 (M., 1995), 401, 297.

Fedorov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), T.2, 249.

Ibid., 116.

Ibid., 229.

Ibid.

V. N. Chekrygin to N. N. Punin, February 7, 1922; Sovetskoe iskusstvoznanie (Soviet art studies), 1976, vol. 2, 330.

Ibid.

A. K. Gorsky, “Ogromnyi ocherk” (An enormous sketch); Gorsky and N. A. Setnitsky, Sochinenya (Works) (M., 1995), 242.

Fedorov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), T.2, 202.

Ibid., 404.

Fedorov, Sobranie sochineny (Collected works), T.1, 401.

Ibid., T.2., 231.

A. K. Gorsky, Organizatsya mirovozdeistivya (Organization of world-transformation); Gorsky and Setnitsky, Sochinenya (Works), 166, 179.

V. N. Muravyov, Vseobshaia proizvoditel’naia matematika (Universal productive mathematics); Muravyov, Sochinenya (Works), vol. 2, book 2 (M., 2011), 133.

Ibid., 137, 138.

V. N., Muravyov, Kul’tura budushego (Culture of the future); Muravyov, Sochinenya (Works), vol. 2, book 2, 177.

Ibid., 175.

Gorsky, Organizatsya mirovozdeistivya (Organization of world-transformation); Gorsky and Setnitsky, Sochinenya (Works), 164.

Gorsky, “Ogromnyi ocherk” (An enormous sketch); Gorsky and Setnitsky, Sochinenya (Works), 200, 204.

Ibid., 193–94.

Gorsky and Setnitsky, Sochinenya (Works), 200, 277.

Gorsky, Organizatsya mirovozdeistivya (Organization of world-transformation); Gorsky and Setnitsky, Sochinenya (Works), 153.

Translated from the Russian by Anastasiya Osipova.