Among the jokes in President Barack Obama’s 2016 White House Correspondents’ Dinner address were a few targeting Senator Bernie Sanders. Sanders was running a surprisingly strong campaign against former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination:

What an election season. For example, we’ve got the bright new face of the Democratic Party here tonight—Mr. Bernie Sanders! (Applause.) There he is—Bernie! (Applause.) Bernie, you look like a million bucks. (Laughter.) Or to put it in terms you’ll understand, you look like 37,000 donations of 27 dollars each. (Laughter and applause.)

A lot of folks have been surprised by the Bernie phenomenon, especially his appeal to young people. But not me, I get it. Just recently, a young person came up to me and said she was sick of politicians standing in the way of her dreams. As if we were actually going to let Malia go to Burning Man this year. (Laughter.) That was not going to happen. (Laughter.) Bernie might have let her go. (Laughter.) Not us. (Laughter.)

I am hurt, though, Bernie, that you’ve distancing yourself a little from me. (Laughter.) I mean, that’s just not something that you do to your comrade. (Laughter and applause.)1

The last joke points to the socialist opening Sanders’s campaign cut into US politics. At first glance, it seems like red-baiting, Obama’s thinly veiled reminder that Sanders was a self-identified socialist and thus politically unacceptable. But this reminder could also have been less red-baiting than it was simply highlighting the fact that Sanders wasn’t actually a member of the Democratic Party, and so wasn’t Obama’s party comrade at all. Sanders was running for the Democratic nomination, but he wasn’t a Democrat. An additional layer to the joke appears when we recall the US right’s attacks on Obama as himself a socialist or communist. For eight years, the right excoriated Obama as the most radical left-wing president the US has ever had. Calling out “Comrade Obama,” it associated Obama with Lenin and Stalin, Che and Mao. This right-wing context makes sense of the unexpected appearance of “comrade” in the words of a US president when we recognize that the joke points not to Sanders as a comrade but to Obama as a comrade. Obama is referring to himself as Sanders’s comrade, to himself as someone who shares with Sanders a common political horizon, the emancipatory egalitarian communist horizon denoted by the term “comrade.” If they are on the same side, if Obama is Sanders’s comrade, then Obama should have been able to expect a little solidarity.

The term “comrade” points to a relation, a set of expectations for action. It doesn’t name an identity; it highlights the sameness of those who share a politics, a common horizon of political action. If you are a comrade, you don’t publicly distance yourself, even a little bit, from your party. Comradeship binds action and in this binding works to direct action toward a certain future. For communists this is the egalitarian future of a society emancipated from the determinations of capitalist production and reorganized according to the free association, common benefit, and collective decisions of the producers.

This essay presents four theses on the comrade.

Survivors and Systems

Two opposed tendencies dominate contemporary left theory and activism: survivors and systems. The first inhabits social media, academic environments, and some activist networks. It is voiced through intense attachment to identity and appeals to intersectionality. The second predominates in more aesthetic and conceptual venues as a post-humanist concern with geology, extinction, algorithms, “hyperobjects,” bio-systems, and planetary exhaustion.2 On the one side, we have survivors, those with nothing left to cling to but their identities, often identities forged through struggles to survive and attached to the pain and trauma of these struggles.3 On the other, we have systems, processes operating at a scale so vast, so complex, that we can scarcely conceive them let alone affect them.4

These two tendencies correspond to neoliberal capitalism’s dismantling of social institutions, to the intensification of capitalism via networked personalized digital media and informatization, what I call “communicative capitalism.”5 More and more people experience more and more economic uncertainty, insecurity, and instability. Jobs are harder to find, easier to lose. Most people can’t count on long-term employment, or expect that benefits like health insurance and retirement packages will be part of their compensation. Many people’s work is more precarious—flex-work, temp-work, contract-work—ideologically garnished as “entrepreneurial.” Unions are smaller and weaker. Schools and universities face cuts to budgets and faculty, additions of administrators and students, more debt, less respect. Pummeled by competition, debt, and the general dismantling of the remnants of public and infrastructural supports, families crumble. Neoliberal ideology glosses the situation as one where individuals have more choice, more opportunity to exercise personal responsibility.

Carl Schmitt famously characterized liberalism as replacing politics with ethics and economics.6 Correlatively, we should note the displacement of politics specific to neoliberalism. There is individualized self-cultivation, self-management, self-reliance, self-absorption, and—at the same time—impersonal determining processes, circuits, and systems. We have responsible individuals, individuals who are responsibilized, treated as loci of autonomous choices and decisions, and we have individuals encountering situations that are utterly determined and outside their control. Instead of ethics and economics, neoliberalism’s displacement of politics manifests in the opposition between survivors and systems. The former struggle to persist in conditions of unlivability rather than to seize and transform these conditions. The latter are systems and “hyperobjects” determining us, often aesthetic objects or objects of a future aesthetics, something to view and diagram and predict and perhaps even mourn, but not to affect.7

Survivors experience their vulnerability. Some even come to cherish it, to derive their sense of themselves from their survival against all that is stacked against them. Sociologist Jennifer Silva interviewed a number of working-class adults in Massachusetts and Virginia.8 Many emphasized their self-reliance. Other people were likely to continue to fail or betray them. To survive, they could count only on themselves. Some of the young adults described struggles with illness and battles with addiction, the challenge of overcoming dysfunctional families and abusive relationships. For them, the fight to survive is the key feature of an identity imagined as dignified and heroic because it has to produce itself by itself.

Accounts of systems are typically devoid of survivors. Human lives don’t matter; the presumption that they matter is taken to be the epistemological failure or ontological crime in need of remedy. Bacteria and rocks, planetary or even galactic processes, are what need to be taken into account, brought in to redirect thought away from anthropocentric hubris. When people appear, they are the problem, a planetary excess that needs to be curtailed, a destructive species run amok, the glitch of life.

The opposition between survivors and systems gives us a left devoid of politics. Both tendencies render political struggle, the divisive struggle over common conditions on behalf of a common project and future, unintelligible. In the place of politics we have the fragmenting assertion of particularity, of unique survival, and the obsession with the encroaching, unavoidable, impossibility of survival. Politics is effaced in the impasse of individualized survivability under conditions of generalized non-survival, of extinction.

However strong the survivors and systems tendencies may be on the contemporary left, our present setting still provides openings for politics. Here are four.9 First, communicative capitalism is marked by the power of many, of number. Capitalist and state power emphasizes big data and the knowledge generated by finding correlations in enormous data sets. Social media is driven by the power of number: How many friends and followers, how many shares and retweets? On the streets and in the movements, we see further emphasis on number—the many rioting, demonstrating, occupying, blockading. Second, identity is no longer able to ground a left politics uttered in its name. No political conclusions follow from the assertion of a specific identity. Attributions of identity are immediately complicated, critiqued, even rejected. Third, because of the astronomical increase in demands on our attention that circulate in communicative capitalism, a series of communicative shortcuts have emerged: hashtags, memes, emojis, reaction GIFs, as well as linguistic patterns optimized for search engines (lists, questions, indicators, hooks, and lures).10 These shortcuts point to the prominence of generic markers, common images and symbols that facilitate communicative flow, that keep circulation liquid. If we had to read, much less think about, everything we shared online, our social-media networks would slow down, clog up. The generic serves increasingly as a container for multiplicities of incommunicable contents. Fourth, the movements themselves have come up against the limits of horizontality, individuality, and rhetorics of allyship that presuppose fixed identities and interests. The response has been renewed interest in the politics of parties and questions of the party form, renewed emphasis on organizing the many. Cutting through and across the impasse of survivor and system is a new turn toward arrangements of the many and institutions of the common.11

Against this background, I consider the comrade. The comrade figures a political relation that shifts us away from preoccupations with survivors and systems, away from suppositions of unique particularity and the impossibility of politics, and toward the sameness of those fighting on the same side.

Thesis One: “Comrade” names a relation characterized by sameness, equality, and solidarity. For communists, this sameness, equality, and solidarity is utopian, cutting through the determinations of capitalist society.

Multiple figures of political relation populate the history of political ideas. For centuries, political theorists have sought to explain power and its exercise via expositions of the duties and obligations, virtues and attributes of specific political figures. Machiavelli made the Prince famous (although he wasn’t alone in writing for or about princes). There are countless treatises on kings, monarchs, and tyrants. Political theorists have investigated the citizen and foreigner, neighbor and stranger, lord and vassal, friend and enemy. Their inquiries extend into the household: master and slave, husband and wife, parent and child, sister and brother. They include the workplace: schoolmaster and pupil, bourgeois and proletarian. Yet for all these figurations of power, its generation, exercise, and limits, there is no account of the comrade. The comrade does not appear.

The absence of the comrade in American political theory could be a legacy of the Cold War. John McCumber’s history of the impact of McCarthyism on the discipline of philosophy in the US notes the twenty-year disappearance of political philosophy from the field.12 Political philosophy only reemerged in 1971 with John Rawls’s Theory of Justice, a book that subordinated politics to questions of moral justification and secluded actual political and social issues behind a veil of ignorance. But the Cold War can’t account for why few socialist and communist theorists produced systematic accounts of the characteristics and expectations of comrades. One exception is Alexandra Kollontai. Another is Maxim Gorky. Neither provides a systematic or analytical explication of the comrade as a figure of political relation. But they do give us an affective opening into the utopian promise of comradeship.

In her writings on prostitution, sex, and the family from the early years of the Bolshevik Revolution, Kollontai presents comradeship and solidarity as sensibilities necessary for building a communist society. She associates comradeship with a “feeling of belongingness,” a relation among free and equal communist workers.13 “In place of the individual and egoistic family, a great universal family of workers will develop, in which all the workers, men and women, will above all be comrades.”14 “Comrade” points to a mode of belonging opposed to the isolation, hierarchy, and oppression of bourgeois forms of relation, particularly of the family under capitalism. It’s a mode characterized by equality, solidarity, and respect; collectivity replaces egoism and self-assertion. In Russian, the word “comrade,” tovarish, is gender neutral, so it replaces gendered forms of address.

Gorky has a short story from the early twentieth century, published in English in 1906 in The Social Democrat, simply titled “Comrade.” The story testifies to the life-giving power of the word “comrade.” Gorky presents “comrade” as a word that “had come to unite the whole world, to lift all men up the summits of liberty and bind with new ties, the strong ties of mutual respect.”15 The story depicts a dismal, “torturous” city, a city of hostility, violence, humiliation, and rage. In this city, the weak submit to the dominance of the strong. In the midst of this miserable suffering, one word rings out: comrade! And the people cease to be slaves. They refuse to submit. They become conscious of their strength. They recognize that they themselves are the force of life.

When people say “comrade,” they change the world. Gorky’s examples include the prostitute who feels a hand on her shoulder and then weeps with joy as she turns around and hears the word “comrade.” With this word, she is interpellated not as a self-commodifying object to be enjoyed by another, but as an equal in common struggle against the very conditions requiring commodification. Additional examples are a beggar, a coachmen, and young combatants—for all, “comrade” shines like a star that guides them to the future.

Like Kollontai, Gorky associates the word “comrade” with freedom from servitude and oppression, with equality. Like her, he presents the comrade as opposed to capitalist egoism’s exploitation, hierarchy, competition, and misery. And like Kollontai, Gorky links comradeship to a struggle for and vision of a future in which all will be comrades.

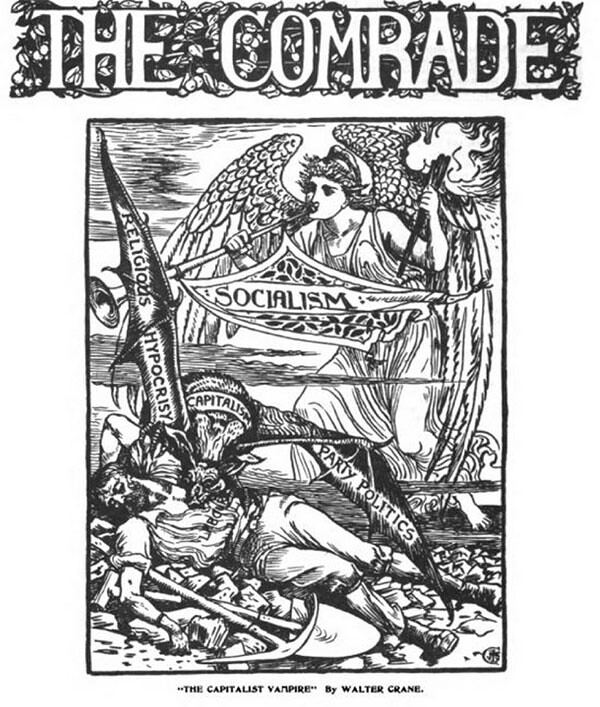

Similarly romantic celebrations of relations between comrades infuse the American journal The Comrade, published between 1901 and 1905. The Comrade was an illustrated monthly publication, targeted toward ethically minded middle-class socialists. It featured poems, short fiction, articles on industry and the conditions of the working classes, translations from European socialists, and autobiographical essays such as “How I Became a Socialist.” Inspired in part by Walt Whitman’s “manly love of comrades,” the journal echoes Whitman’s homoeroticism, homosociality, and celebratory queerness.16 Comrade relations are relations of a new type, relations that disrupt the confines of the family and heteropatriarchy. The short story “The Slave of a Slave” is a good example: the protagonist is a tomboy who tries to save a poor woman from her brutal husband and, failing to do so, nevertheless expresses gratitude that she herself will never be a woman.17 This queerness reappears today in contemporary Chinese where the term “comrade,” tongzhi, also means gay.

The Comrade featured poems extoling the comrade and comradeship. George D. Herron’s “A Song of To-Morrow” dreamed “Of comrade-love, will fill the world.”18 Edwin Markham’s poem “The Love of Comrades” evoked comrade-bees. An additional Herron poem turned “comrade” into a prefix: comrade-day, comrade-home, comrade-march, comrade-future, comrade-stars.19 Russian constructivist Alexander Rodchenko expanded the field of comradeship still further. He included comrade objects, comrade things. In 1925 he writes: “Our things in our hands must be also equals, also comrades.”20

These examples from Bolsheviks and The Comrade link comradeship to a future characterized by equality and belonging, by a love and respect between equals so great that it can’t be contained in human relations but spans to include insects and galaxies (bees and stars) and objects themselves. “Comrade” marks the division between the world of misery we have and the egalitarian communist world that will be.

As in Russian revolutionary history and early-twentieth-century Whitman-inspired homosocialism, so in contemporary Chinese does the term “comrade,” tongzhi, replace hierarchical and gendered designations of relation with an “ideal of egalitarianism and utopianism.” According to Hongwei Bao, tongzhi is intrinsically queer: it “maps social relations in a new way, a way that opens the traditional family and kinship structure to relations and connections between strangers who share the same political views, and it transforms private intimacy into public intimacy.”21 Bao’s queer comrades resonate with Jason Frank’s reading of Whitman’s ethos of comradeship in his Calamus poems: erotic comradely relations destabilize and overcome “identitarian differences of locality, ethnicity, class, and occupation, sex, race, and sexuality.”22

Kollontai, Gorky, and their queer comrades inspire a first thesis on the comrade: comrade is a generic and egalitarian—and for communists and socialists, utopian—figure of political relation. The egalitarian dimension of “comrade” names a relation that cuts through the determinations given by the present. This sense of comrade comes through in the conclusion of The Wretched of the Earth as Fanon appeals repeatedly to his readers as comrades: “Come, comrades, the European game is finally over, we must look for something else”; and the last line of the book, “For Europe, for ourselves, and for humanity, comrades, we must make a new start, develop a new way of thinking, and endeavor to create a new man.”23 Comrade is a mode of address appropriate to this endeavor. It is egalitarian, generic, and abstract and, in the context of hierarchy, fragmentation, and oppression, utopian.

Today, in a setting that is ever-more nationalist and authoritarian, increasingly competitive, unequal, and immiserated, in a world of anthropocenic exhaustion, it’s hard to recapture the hope, futurity, and sense of shared struggle that was part of an earlier revolutionary tradition. What, then, is comradeship for us? My wager is that a speculative-compositive account of comradeship, one that distills common elements out of the use of “comrade” as a mode of address, figure of belonging, and container for shared expectations, can provide us with a view of political relation necessary for the present. Comrades are more than survivors. They are those on the same side of a struggle for an emancipated egalitarian world.

Thesis Two: Anyone but not everyone can be a comrade

Who is the comrade? This question animates Greta Garbo’s first scene in Ernst Lubitch’s 1939 film, Ninotchka.24 Iranoff, Buljanoff, and Kopalski are three minor Soviet trade officials who are in Paris to arrange the sale of jewels confiscated from Russian aristocrats. Alas, they give in to bourgeois temptations and become corrupted by the decadence of Parisian wealth, donning tuxedos and drinking champagne. Moscow gets wind of these developments and sends a comrade to straighten them out. As the scene opens, Iranoff, Buljanoff, and Kopalski are at the train station to meet their comrade. But who is the comrade? “How can we find somebody without knowing what he looks like?” asks Kopalski. Scanning the passersby, Iranoff thinks he sees the comrade. “That must be the one!” agrees Buljanoff. “Yes. He looks like a comrade.” But looks can be deceiving. As they walk toward him, the man they’ve identified greets someone: “Heil Hitler!” Iranoff shakes his head, “That’s not him.” Anyone could be their comrade. But not everyone. Some people are clearly not comrades. They are enemies. Iranoff, Buljanoff, and Kopalski can’t figure out who their comrade is by looking at them. Identity has nothing to do with comradeship.

As they wonder what they are going to do, they are approached by a woman (Garbo). She announces herself as Nina Ivanova Yakushova, envoy extraordinary. Kopalski and Iranoff note their surprise that Moscow sent a “lady comrade.” Had they known, they would have brought flowers. Yakushova admonishes them. “Don’t make an issue of my womanhood,” she says. “We’re here to work for all of us.” That she is a woman is to be disregarded. Again, identity has nothing to do with comradeship—it’s about work, the work of building socialism.

That anyone but not everyone can be a comrade accentuates how “comrade” names a relation that is at the same time a division. Comradeship is premised on inclusion and exclusion—anyone but not everyone can be a comrade. It is not an infinitely open or flexible relation but one premised on division and struggle. There is an enemy. But unlike Schmitt’s classic account of the political in terms of the intensity of the antagonism between friend and enemy, comradeship doesn’t concern the enemy. The fact of the enemy, of struggle, is the condition or setting of comradeship but it does not determine the relation between comrades. Comrades are those on the same side of the division. With respect to this division, they are the same. Their sameness is that of those who are on the same side. To say “comrade” is to announce a belonging, and the sameness that comes from being on the same side.

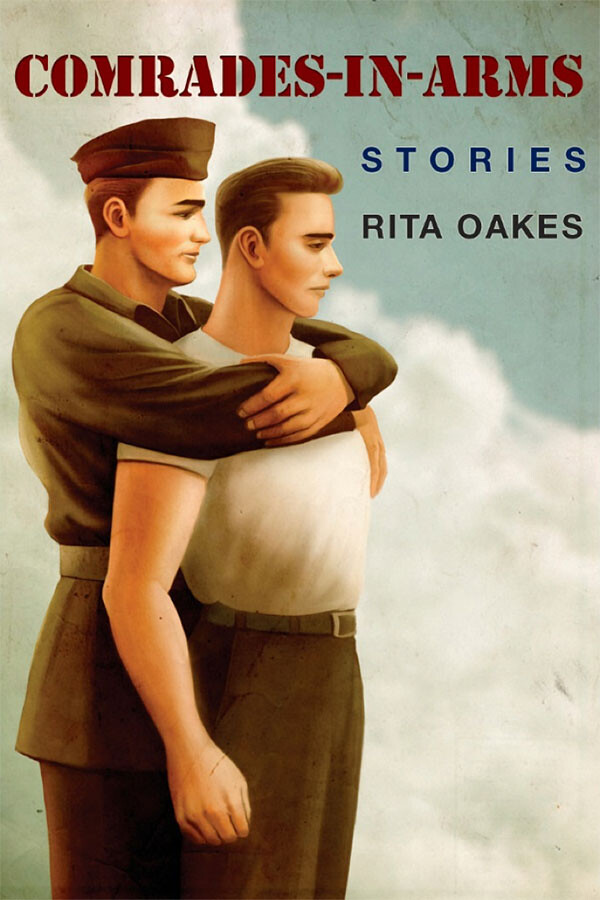

This sameness appears not simply in the relation between party comrades but also in the military expression “comrade-in-arms.” “Comrade-in-arms” designates those who fight on the same side against an enemy, another military, another set of comrades-in-arms. In his introduction to The Wretched of the Earth, Jean-Paul Sartre writes that “every comrade in arms represents the nation for every other comrade. Their brotherly love is the reverse side of the hatred they feel for you.”25 Sartre’s slide into the language of brotherhood brings out the ethnic and blood underpinnings of the nation that Schmitt’s term “friend” occludes. Sartre alerts us, then, not only to comrades-in-arms’ common relation to the enemy (the hated, the one to be killed), not only to how comrades-in-arms are those on the same side, but also to the distinction between the comrade-in-arms and the comrade as a figure of belonging in the socialist and communist political tradition: the solidarity of comrades is not an inverted hatred. As we saw with Kollontai and Gorky, it’s a response to fragmentation, hierarchy, isolation, and oppression. In their being on the same side, comrades confront and reject fragmentation, hierarchy, isolation, and oppression with an egalitarian promise of belonging.

To reiterate: that anyone but not everyone can be a comrade highlights how comradeship designates a relation and a division—us and them—a political relation but one that is not the same as the relation between friend and enemy, an absolute and exclusive state relation. Instead, there is a space of possibility: anyone can be a comrade, but not everyone.

Generic Not Unique

Evoking those on the same side, “comrade” is a term of address and designation of relationship in the military, sometimes among schoolmates, and typical in socialist and communist parties. We gain some clarity regarding the emancipatory egalitarian kernel of the term when we distinguish comradeship from other relations.

The relation between comrades is not a kinship relation. It is not the same as that between brothers, sisters, parents and children, spouses, or cousins. One’s cousin may be one’s comrade, but when adding “comrade” one is saying something else, designating an aspect of relation that the relation between cousins does not designate. The term “comrade” adds a political element, highlighting the fact that the cousins are on the same side. They share a politics that exceeds their blood or kinship relation. Kin may and do disagree politically. We may be related by blood without sharing a politics. The same holds for marriage. People can be spouses without being comrades. Frida Kahlo famously said of Diego Rivera, whom she married twice, “Diego is not anybody’s husband and never will be, but he is a great comrade.”26 And just as the relationship between comrades is not mediated by blood or marriage, so is it not mediated via inheritance. Rather than passing on property and privilege, comrade cuts against them, disrupting their hierarchies with the egalitarian insistence of those fighting together on the same side.

The comrade is not the neighbor.27 Living near someone does not make them your comrade. We may be part of the same locality, the same community, tribe, or neighborhood, without being comrades. Comradeship does not designate a spatial relation or an obligation stemming from proximity or shared sociality.

The comrade is not the citizen. Citizenship is a relation mediated by the state. Comradeship exceeds the state. It does not take the state as its frame of reference. One finds comrades all over the world. The Comrade is interesting on this score as it collects letters, speeches, articles, and other sorts of writings from European socialists. Even as the new US socialists are not yet part of the “international,” they emphasize and affiliate with an international political movement. Comrade’s rupture of citizen also manifests when we note state fear of communists as traitors, as those with loyalties to an organization other than the state. In the US during the Cold War (and still today in right-wing rhetoric), “comrade” was used in a derogatory way to accentuate the dangerous otherness of communists. Comrades may oppose other citizens.

The relation between comrades is not the same as the relation between friends. Claudio Lomnitz’s The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón helps illustrate the point. Lomnitz describes the lifeworld of the Partido Liberal Mexicano, a transnational network of revolutionary libertarian communists operating in Mexico and the US and engaging in the Mexican Revolution. Mexican émigrés and exiles living in the US intertwined political work and the work to survive under capitalist conditions. Devoting everything to their cause, some comrades opened themselves up to the opportunism of the less committed, to the exploitation of those who began to prioritize making their own way in the US. Tensions around sharing and work, politics and commitment, bled into suspicion of infiltrators. Lomnitz writes, “And if a comrade was thought to be opportunistic and had personal ambitions, that person could be prone to selling out and maybe even to selling out his comrades. For this reason, the line between personal dislikes and suspicions of treason could get thin, and work was required to keep them distinct.”28 Comrades may be friends but friendship and comradeship is not the same. We see this most clearly when friendships fray. Personal dislike does not mean that the person is not a comrade. In tight associations, comrade and friend relations blur and overlap. Maintaining the difference, the distance, between them takes work, important work. Comradeship requires a degree of alienation from the needs and demands of personal life to which friends must attend.

We learn from Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics that friendship is a direct relation between two people for the benefit of each other. It’s a relationship anchored in the person, for the benefit or excellence of the individual. In contrast, comradeship is broad—bees and stars, someone previously unknown now revealed as a comrade. Comradeship extends through intimate relations to stretch into relations with those we don’t know personally at all. Anyone can be a comrade, whether they like me or not, whether they are like me or not.

The distinction between the comrade and the friend points to the inhuman dimension of the comrade: comradeship has nothing to do with the person or personality in its specificity; it’s generic. Comradeship is abstract from the specifics of individual lives, from the uniqueness of lived experience. It concerns rather the sameness that comes from being on the same side in a political struggle. In this sense, the comrade is liberated from the determinations of specificity, freed by the common political horizon. Ellen Schrecker makes this point in her magisterial account of anticommunism in the United States. During the McCarthy period of communist persecution, there was a common assumption that “all Communists were the same.”29 Communists were depicted as puppets, cogs, automatons, robots, even slaves. In the words of “one of the McCarthy era’s key professional witnesses,” people who became communist were “no longer individuals but robots; they were chained in an intellectual and moral slavery that was far worse than any prison.”30 The truth underlying the hyperbolic claims of this anticommunist is the genericity of the comrade, of comrade as a disciplined and disciplining relation that exceeds personal interests. Comradeship isn’t personal. It’s political.

The “other relations”—kin, neighbor, citizen, friend—index degenerations of comradeship, errors that comrades make when they substantialize comradeship via race, ethnicity, nationality, and personality. We see this substantializing error in Italian and German uses of “comrade” (camerata, Kamerad) as a term of address. For them, “comrade” is a fascist political name. Yet this substantialization is clearly a degeneration: the fascist cannot say that anyone could be a comrade. German leftists (socialists, communists, anarchists) instead use Genosse/Genossen and Italians use compagno/compagna. Genosse comes from the old German word “ginoz,” which designated the shared enjoyment of something, enjoying something with someone.31 Back to my point: the emancipatory egalitarian energy of “comrade,” its life-giving capacity and ability to map social relations in a new way, is a product of its genericity—anyone but not everyone can be a comrade. When comradeship bleeds into nationality, ethnicity, or race, when it is mistaken for a relation supposed to benefit an individual, and when it is equated with relations mediated by the state, the cut of the generic is lost.

Thesis Three: The Individual (as a locus of identity) is the “other” of the comrade

Comradeship is not a relation of identity. As we see in Ninotchka, an issue should not be made of the comrade’s womanhood; all have work to do. Comrade does not specify an identity. On the left, comrade is a term of address that attaches to proper names—“Comrade Yakushova.” The proper name carries the individual identity; the term of address asserts a sameness. Comrade takes the place of “sir,” “madam,” “citizen.” Comrade negates the specificity of a determined title, a title that inscribes differentiation and hierarchy. It replaces it with a positive insistence on an equalizing sameness.

Oxana Timofeeva emphasizes that in comradeship identity vanishes.32 Timofeeva gives the example of the masquerade used by Bolsheviks undercover. Anyone could be under that mustache. Schrecker provides a further example, a statement from General Herbert Brownell, attorney general under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Brownell’s suspicions of communists were heightened because, in his words, it was “almost impossible to ‘spot’ them since they no longer use membership cards or other written documents which will identify them for what they are.”33 In these examples, it’s the generic comrade who appears, carried by an individual person, yet the one who appears is one of many; it could be anyone. Schrecker quotes Herbert Philbrick, an undercover informer: “Anyone can be a Communist. Anyone can suddenly appear as a Communist party member—close friend, brother, employee or even employer, leading citizen, trusted public servant.”34

Berthold Brecht’s cantata The Measures Taken (Die Massnahme) similarly explores the antithetical relation between individual identity and the comrade. Four agitators are on trial before a party central committee (the Control Chorus) for the murder of their young comrade. The agitators describe how they went undercover in order reach Chinese workers they were trying to organize. Each agitator had to efface their identity, to be “nameless and without a past, empty pages on which the revolution may write its instructions.”35 Each agitator, including the young comrade, agreed to fight for communism and be themselves no longer. They all put on Chinese masks, appearing as Chinese rather than as German and Russian. Repeatedly, the young comrade substitutes his judgment for that of the Party, encouraging action before the time is right. He can see with his own two eyes that “misery cannot wait.” He tears up the Party writings. He tears up and off his mask. He substitutes his judgment for the Party’s, thereby exposing them all. Now fleeing Chinese authorities, the agitators and the young comrade race to escape the city. Yet they realize that since the young comrade has been exposed, since he is now identifiable, they will have to kill him. The young comrade agrees. They shoot him, throw him into a lime pit that will burn away all traces of him, and return to their work.

Comrades are multiple, replaceable, fungible. They are elements in collectives, even collections. School children may refer to each other or be referred to as comrades. In several Romance languages, “comrade” originates as a term for those who travel together, who share a room or enjoy something together. To be a comrade is to share a sameness with another with respect to where both are going.

In post-1991 Russia’s transition to capitalism, the term “comrade” started to become discredited. Alla Ivanchikova tells me that this is a political struggle, fought through etymology. New etymologies sought to depoliticize and mock the term. They highlighted its origin in the word “tovar” or commodity, a good for sale.36 Ivanchikova explains that “this clearly serves the purpose of showing that underneath all talk of ‘comradery’ there are monetary and market relations that rule the day. Any comrade (tovarish) is a commodity (tovar), if you pay the right price.”37 Counter-etymologies insist that tovar is much older than commodity or goods produced for sale. Tovar derives from an ancient word for military camp, tovarŭ.38 Soldiers called themselves comrades.

Underlying this etymological warfare is an assumption of sameness. Interchangeability, whether soldier or commodity, schoolchild or fellow traveler, characterizes the comrade. As with puppets, cogs, robots, and slaves, commonality arises not out of identity—one can’t identify a comrade—not out of who one is, but out of what is being done—fighting, circulating, studying, traveling, enjoying the same things. Political comrades are on the same side. Communist comrades are those on the same side of the struggle to emancipate society from capitalism and create new, egalitarian modes of free association and collective decision-making for common benefit.

For anticommunists, the instrumentalism of comrade relations appears horrifying. Combined with the machinic impersonality and fungibility of comrades, the fact that relations between comrades are produced for an exterior purpose, that they are means rather than ends in themselves, seems morally objectionable. This objection fails to acknowledge the specificity of comradeship as a political relation, being on the same side of struggle. It omits the way political work focuses on ends beyond the individual and so necessarily requires collective coordination. And it contracts and contains the space of meaning into self-relations, as if the abstracted, generic relations among those faithful to a political truth could only be the result of manipulation. In an interview with Vivian Gornick, a former member of the CPUSA described his life of meetings, actions, May Day parades, selling the Daily Worker, and endlessly discussing Marx and Lenin as “beyond good or bad,” “sweeping, powerful,” “intense, absorbing, filled with a kind of comradeship I never again expect to know.”39 He was useful, living in the service of a struggle of world-historical significance.

Thesis Four: The relation between comrades is mediated by fidelity to a truth. Practices of comradeship materialize this fidelity, building its truth into the world.

By the end of the nineteenth century, “comrade” was a prominent term in socialist circles. Kirsten Harris finds the first recorded socialist evocation of comradeship in English in the journal Justice in 1884. Some English socialists were inspired by Whitman’s vision of the deep fellowship and interconnectedness of comrades. It spoke to their sense that the relation among those in socialist struggle, as well as in the new society to come, was more than brotherhood (prominent in the labor movement) or fraternity (an ideal from the French Revolution). And the term’s military background made “comrade” an able carrier of the ideal of a “bond that is forged when a common cause is fought side by side.”40 The English embrace of Whitman resonated with US socialists. In a short essay in The Comrade published in 1903, W. Harrison Riley recounted some of his encounters with Marx (whom he said “was as good to look at as to listen to,” “well built and remarkably good looking”). Riley observed that “the Internationalists addressed each other as ‘Citizen,’ but I disliked the designation and frequently substituted Whitman’s greeting, ‘Comrade.’”41

Riley’s gesture to Whitman notwithstanding, “comrade” was already part of the political vocabulary of German socialists. In his writings, Marx used “comrade” to designate those in the same political party, those sharing the same politics. “Party” referred not just to a formal organization but to broader political movement. In his well-known letter to Kugelmann on the Paris Commune, Marx praises “our heroic Party comrades in Paris.”42 The Communards were not Marx’s comrades in a specific party but in the party understood in a “broad historical sense.”43 They were all on the same side, that of “real people’s revolution.”44 In a text for the International Workingmen’s Association written in 1866, Marx drew out this political dimension of “comrade”: “It is one of the great purposes of the Association to make the workmen of different countries not only feel but act as brethren and comrades in the army of emancipation.”45 More than union brothers involved in local and national struggles, members of the IWA would be comrades in political struggle, fighting on the same side, the side of their class in the struggle of labor against capital. As comrades in an army of emancipation, they would combine and generalize their efforts. No longer would the differences between foreign and domestic workers be able to be used against them. As comrades they were all the same.

The idea that comrades are those fighting on the same side of a political struggle opens up into the fourth thesis. The “same side” points to the truth comrades are faithful to, the political truth that unites them. “Fighting” indexes the practices through which comrades enact their fidelity and work to materialize truth in the world.

The notions of truth and fidelity at work here come from Alain Badiou. In brief, Badiou rejects the idea that truth is a proposition or judgment to argue that truth is a process. The process begins with the eruption of something new, an event. Because an event changes the situation, breaks the confines of the given, it is undecidable in terms of the given; after all, it is something entirely new. Badiou argues that this undecidability “induces the appearance of a subject of the event.”46 This subject isn’t the cause of the event. It’s an effect of or response to the event, “the decision to say that the event has taken place.” Grammar might seduce us into rendering this subject as “I.” We should avoid that temptation and recognize “subject” here as designating an inflection point, a response that extends the event. The decision that a truth has appeared, that an event has occurred, incites a process of verification, the “infinite procedure of verification of the true.” Badiou calls this procedure an “exercise of fidelity.” Fidelity is a working-out and working-through of the truth, an engagement with truth that extends out into and changes the world.

Peter Hallward draws out some of the implications of Badiou’s conception of truth. First, it is subjective. Only those faithful to an evental truth, only those involved in its working out, recognize it as true. Second, fidelity is not blind faith; it is rigorous engagement unconcerned with individual personality and incorporated into the body of truth that fidelity generates. Hallward writes:

Fidelity is, by definition, ex-centric, directed outward, beyond the limits of a merely personal integrity. To be faithful to an evental implication always means to abandon oneself, rigorously, to the unfolding of its consequences. Fidelity implies that, if there is truth, it can be only cruelly indifferent to the private as such. Every truth involves a kind of anti-privatization, a subjective collectivization. In truth, “I” matter only insofar as I am subsumed by the impersonal vector of truth—say, the political organization, or the scientific research program.47

The truth process builds a new body. This body of truth is a collective formed to “work for the consequences of the new,” and this work, this collective, disciplines and subsumes the faithful.48 Third, collectivity does not imply uniformity. The infinite procedure of verification incorporates multiple experiments, enactments, and effects.

As a figure of political relation, the comrade is a faithful response to the evental rupture of crowds and movements, to the egalitarian discharge that erupts from the force of the many where they don’t belong.49 Comrades demonstrate fidelity through political work, through their radical action and militant engagement. This practical political work extends the truth of the emancipatory egalitarian struggle of the oppressed into the world, holding open the gap it inscribes in its setting and building a new body of truth. In the socialist and communist tradition, this body has been the party, understood in both its historical and formal sense.

In Ninotchka, Nina Ivanova Yakushova can’t tell who her comrades are by looking at them. The Party has told her who to look for, but she has to ask. After Iranoff identifies himself, Yakushova tells him her name and the name and position of the party comrade who authorized her visit. Iranoff introduces Buljanoff and Kopalski. Yakushova addresses each as comrade. But it’s not the address that makes them all comrades. They are comrades because they are members of the same party. The party is the organized body of truth that mediates their relationship. This mediation makes clear what is expected of comrades—work. Iranoff, Buljanoff, and Kopalski have not been doing the work expected of comrades, which is why Moscow sent Yakushova to oversee them in Paris. That Kopalski says they would have greeted her with flowers demonstrates their “embourgeoisement,” the degeneration of their sense of comradeship. They are all there for work. Gendered identity and hierarchy don’t mediate relations between comrades. The practices of fidelity to a political truth, work toward building this truth in the world, do.

Comradeship is a disciplining relation: expectations, and the responsibility to meet these expectations, constrain individual action and generate collective capacity. Raphael Samuel describes the life of comrades in the Communist Party of Great Britain in the 1930s and ’40s.50 The Party held meetings, rallies, and membership drives. It published and distributed a wide array of literature. It organized demonstrations, mobilized strike support, carried out emergency protests.51 Samuel treats communist organizational passion as the discipline of the faithful—efficiency in the use of time, solemnity in the conduct of meetings, rhythm and symmetry in street marches, statistical precision in the preparation of reports. He writes, “To be organized was to be the master rather than the creature of events. In one register it signified regularity, in another strength, in yet another control.”52 Truth has effects in the world; comrade work realizes these effects.

Conclusion

“Comrade” is more than a term of address. As a figure of political relation, it’s a carrier of expectations for action, the kinds of expectations that those on the same side have of each other, expectations that should be understood via Badiou as the “discipline of the event.”53 Obama’s joke notes one such expectation: you don’t distance yourself from your comrades.

Kollontai affirms it: the primary virtue of comrades is solidarity; fidelity is demonstrated through reliable, consistent, practical action. Differences between parties often turn on what comrades can expect of each other, on what it means to be a comrade. Broadly speaking, comrades in most revolutionary socialist and communist parties are expected to engage in the struggles of the oppressed, organize for revolution, and maintain a certain unity of action. Absent expectations of solidarity, “comrade” as term of an address is an empty signifier. Rather than figuring the political relation mediated by the truth of communism, it becomes an ironic or nostalgic gesture to past utopian hope.

To demonstrate how the figure of the comrade can be a figure for us, an operator for a politics of those engaged in emancipatory egalitarian struggle, I’ve offered four theses:

1. “Comrade” names a relation characterized by sameness, equality, and solidarity. For communists, this sameness, equality, and solidarity is utopian, cutting through the determinations of capitalist society.

2. Anyone but not everyone can be a comrade.

3. The Individual (as a locus of identity) is the “other” of the comrade.

4. The relation between comrades is mediated by fidelity to a truth. Practices of comradeship materialize this fidelity, building its truth into the world.

Together they articulate a generic political component activated through divisive fidelity to the emancipatory egalitarian struggle for communism. A comrade is one of many fighting on the same side.

“Here’s the Full Transcript of President Obama’s Speech at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner,” Time, May 1, 2016 →.

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Wendy Brown, “Wounded Attachments,” Political Theory 21, no. 3 (August 1993): 390–410. See also Robin D. G. Kelley’s critique of black student activists’ embrace of the language of personal trauma, “Black Study, Black Struggle,” Boston Review, March 7, 2016 →.

Jodi Dean, “The Anamorphic Politics of Climate Change,” e-flux journal 69 (January 2016) →.

Jodi Dean, “Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics,” Cultural Politics 1, no. 1 (2005): 51–74.

Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political (expanded edition), trans. George Schwab (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

Benjamin Bratton, “Some Trace Effects of the Post-Anthropocene: On Accelerationist Geopolitical Aesthetics,” e-flux journal 46 (June 2013) →.

Jennifer M. Silva, Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

For a more thorough discussion see my Crowds and Party (London: Verso, 2016).

Jodi Dean, “Faces as Commons: The Secondary Visuality of Communicative Capitalism,” Open! December 31, 2016.

John McCumber, Time in the Ditch: American Philosophy in the McCarthy Era (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2001) 38–39.

Alexandra Kollontai, “New Woman,” from The New Morality and the Working Class (1918), trans. Salvator Attansio, Marxists Internet Archive →.

Alexandra Kollontai, Communism and the Family (1920), trans. Alix Holt, Marxists Internet Archive →.

Maxim Gorky, “Comrade” (1905), Marxists Internet Archive →.

See also Juan A. Herrero Brasas, Walt Whitman’s Mystical Ethics of Comradeship (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2010); and Kirsten Harris, Walt Whitman and British Socialism: ‘The Love of Comrades,’ (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Amy Wellington, “The Slave of a Slave,” The Comrade 1, no. 6 (1901): 128.

George D. Herron, “A Song of To-Morrow,” The Comrade 3, no. 4 (1903): 83.

George D. Herron, “From Gods to Men,” The Comrade 1, no. 4 (1901): 97.

Quoted in Olga Kravets, “On Things and Comrades,” ephemera 13, no. 2 (May 2013): 421–36 →.

Hongwei Bao, “‘Queer Comrades’: Transnational popular culture, queer sociality, and socialist legacy,” English Language Notes 49, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 2011): 131–37, 132.

Jason Frank, “Promiscuous Citizenship,” A Political Companion to Walt Whitman, ed. John Seery (Lexington, KT: University Press of Kentucky, 2011): 155–84, 164.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004) 236, 239.

I am indebted to Oxana Timofeeva for this example and for the insight that anyone but not everyone can be a comrade.

Jean-Paul Sartre, preface, The Wretched of the Earth, lvi.

Quoted by Hayden Herrera, “Frida Kahlo: Life into Art,” The Seductions of Biography, eds. David Suchoff and Mary Rhiel (New York: Routledge, 1996): 113–17, 115.

For a more complex discussion of the neighbor in its religious, sociopolitical, and mathematical meanings, see Kenneth Reinhard’s entry, “Neighbor,” in the Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon, ed. Barbara Cassin (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015): 706–12.

Claudio Lomnitz, The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón (New York: Zone Books, 2014), 295.

Ellen Schrecker, Many Are the Crimes (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1998), 131.

Ibid., 133.

See the German Wikipedia entry for “Genosse” →.

Oxana Timofeeva, “Communist Spirits: A Pack of Folks,” commentary on the art of Nikolay Oleynikov. Unpublished essay.

Schrecker, Many Are the Crimes, 141.

Ibid.

Bertolt Brecht, The Measures Taken and Other Lehrstücke, eds. John Willett and Ralph Mannheim (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2001), 12.

Kravets, “On Things and Comrades,” 422.

Personal communication.

Serguei Sakhno and Nicole Tersis, “Is a ‘friend’ an ‘enemy’? Between ‘proximity’ and ‘opposition,’” in From Polysemy to Semantic Change, ed. Martine Vanhove (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 2008): 317–39, 334.

Vivian Gornick, The Romance of American Communism (New York: Basic Books, 1977), 56.

Harris, Walt Whitman and British Socialism, 13.

W. Harrison Riley, “Reminiscences of Karl Marx,” The Comrade 3, no. 1 (1903): 5–6, 5.

“Marx to Dr. Kugelmann Concerning the Paris Commune,” April 12, 1871, Marxists Internet Archive →.

For a discussion of the distinction between formal and historical party in Marx’s writing, see Gavin Walker, “The Body of Politics: On the Concept of the Party,” Theory & Event 16, no 4 (2013).

Marx to Kugelmann.

Karl Marx, “Instructions for the Delegates of the Provisional General Council: The Different Questions,” section 2 (1866), Marxists Internet Archive →.

Alain Badiou, Infinite Thought, trans. Oliver Feltham and Justin Clemens (London: Continuum, 2003), 62.

Peter Hallward, Badiou: A Subject to Truth (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 129.

Alain Badiou, Second Manifesto for Philosophy, trans. Louise Burchill (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011), 84.

I develop this argument in Crowds and Party.

Raphael Samuel, The Lost World of British Communism (London: Verso, 2006). The book is comprised of three essays originally published in New Left Review between 1985 and 1987.

For a fuller discussion see Crowds and Party, ch. 5.

Samuel, The Lost World of British Communism, 103.

Alain Badiou, The Rebirth of History (London: Verso, 2012), 69.

All memes are courtesy of the author.