It is time to move on, time to conceive of criticality in non-utopian terms, time to stop mistaking an angel for a prophet (angelos means “messenger”). And it is time to rewrite the art-historical narrative—respecting, not inverting, the logic of the facts.

—Thierry de Duve1

In Orientalism (1978), Palestinian-American critic Edward Said showed how the Orient came to be constructed in Western culture as an Other onto which the West projected its fantasies. The book was a milestone in the development of postcolonial studies, and since its publication the deconstruction of such projections has become a key concern of the discipline. With the emergence of many hitherto unknown documents relating to the so-called Russian avant-garde, interpretations of this movement are changing, and these changes raise the question: Could it be that the standard narrative about the origin and significance of this movement is also a result of Western utopian thinking, guided by a faith in the universality and superiority of Western modernism?

According to this narrative, the movement is rooted in modern thinking that originated in Western Europe—thinking characterized by paradigms such as rationalism, materialism, secularism, and the concept of history as progress. Modern thinking, and especially the October Revolution of 1917 as an implementation of this thinking, is viewed as a precondition for the eruption of a movement that achieved groundbreaking innovations not only in fine art but also in poetry, music, theater, and science. But can this interpretation resist a critical approach in nonutopian terms—terms which, as Thierry de Duve puts it, respect the logic of the facts rather than inverting it? The contents of the new documents send a clear message: they say no.

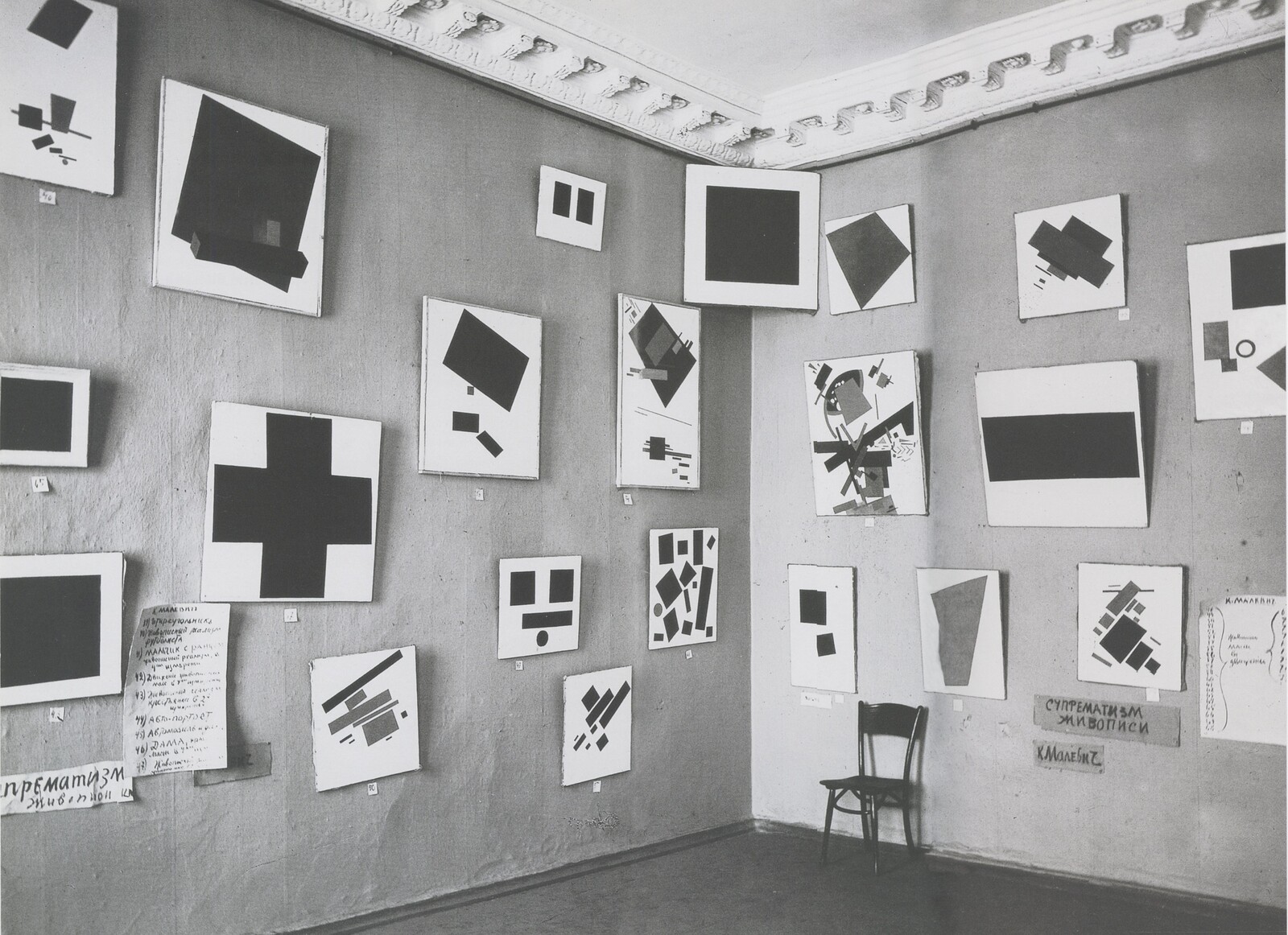

One of the key works of the Russian movement of the early twentieth century is the picture of a black square on a white background by Kazimir Malevich. It was first shown in 1915 during the “Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10,” in what was then Petrograd, hung across the corner of one of the exhibition’s rooms. This was how peasants hung the icons in their houses. As well as the black square—listed in the catalogue simply as Square—Malevich also showed his picture of a red square entitled Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions. What is astonishing here, however, is that Malevich relates these nonfigurative pictures, now considered to be among the high points of secular modernism, to the premodern icon and to Russian peasants living in the Orthodox tradition. How is this contradiction to be understood?

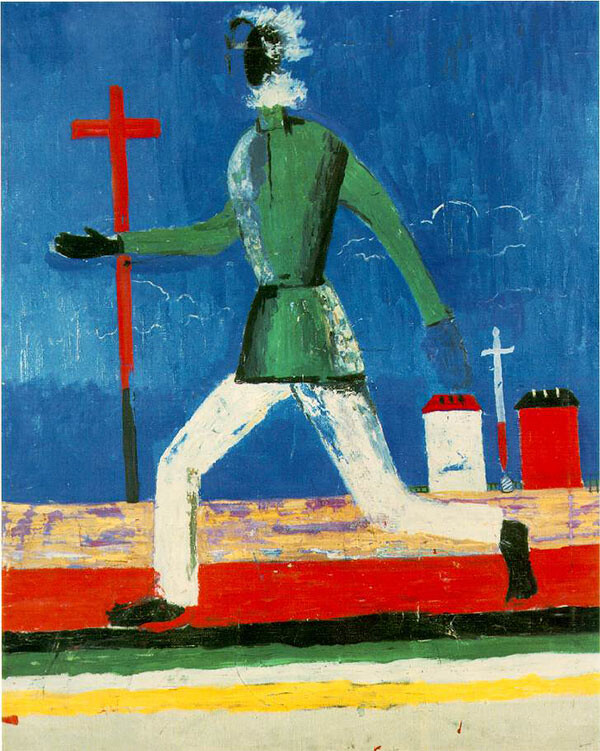

Kazimir Malevich, The Feeling of Danger, 1932–33. Oil on canvas. George Pompidou Art Centre, Paris.

To begin with, we must go back to 1861, the year that Russia’s peasants were released from serfdom and granted extensive self-administration. Rather than becoming private property, the land was to be managed collectively by communities that joined together in peasant councils known as Mir. As a result, ways of life and forms of knowledge that were shaped by the Old Russian Orthodox tradition came to public attention. They were diametrically opposed to the knowledge of the educated urban elites, a knowledge acquired at the universities, referred to by Michel Foucault as institutions of discipline and the transmission of Western knowledge. This knowledge was rational, geared toward the thinking of the natural sciences, skeptical toward religion, driven by a belief in progress. It was a modern knowledge. By contrast, the knowledge of the peasants reflected a premodern understanding of the world. It found visual expression in the icon, which doesn’t depict a reality, because it is a conceptual vision of an alternative to lived reality. It was a firmly established part of everyday life.

The parallel development of these two forms of knowledge was the result of a process of modernization that began with the founding of St. Petersburg, that “window on the West,” by Peter the Great in 1703. But because participation in modernization was restricted to a small group of privileged individuals, it led to a split in Russian society. It was, as Fyodor Dostoyevsky put it, “the first beginning of the epoch when our leading people brutally separated into two parties and then entered into a furious civil war.”2 Before Dostoyevsky, Alexander Herzen had spoken of “two Russias,” meaning the official one and the peasant one.3 And Russian philosopher Boris Groys speaks of a “Europeanized upper class” that often spoke better French than Russian, and of a “peasantry arrested in its cultural tradition.”4 In the words of historian Orlando Figes, for those belonging to the official Russia, the Russia of the peasants was “as exotic and alien … as the natives of Africa were to their distant colonial rulers.”5

With the entry of peasant representatives into public life and the arrival of peasants in the cities, the gulf between the two Russias became apparent. This in turn raised the question of how to deal with this divide. And for the generation that began studying after 1863, when non-aristocrats were first admitted to the universities, the answer to the rural-urban divide was to subject peasant traditions to a process of radical modernization. These students, known as the “’60s generation,” had grown up in the countryside in a deeply religious tradition, and their encounter with the positivist-materialist thinking being taught at the universities triggered an identity crisis to which they responded by rejecting their roots. In such circles, this rejection was symbolized by the widespread gesture of throwing icons brought from home out of the window in the company of like-minded students.

This 1860s generation formed the core of the group of educated and semi-educated individuals who would later go down in history as the “Russian intelligentsia.” Its members advocated Darwinist rationalism and militant atheism with something akin to religious fervor. This is not surprising, as many of them were the sons of the clergy. Many also adopted the aristocrats’ megalomania and taste for violence: “Within the intelligentsia’s circles it was deemed a matter of ‘good taste’ to sympathize with the terrorists and many wealthy citizens donated large sums of money to them.”6

The spiritual father of the intelligentsia was Nikolay Chernyshevsky, author of What Is To Be Done? (1863). In what Indian cultural critic Pankaj Mishra calls “probably the worst Russian novel of the nineteenth century (and the most influential),” Chernyshevsky describes a love story involving the revolutionary Rakhmetov, who bends his emotional life to the needs of the revolutionary struggle.7 The novel is intended as a prologue to a revolution that will be borne not by the working class, which did not yet exist in Russia at the time, but by the peasants. In order to become revolutionaries, however, the peasants must be subjected, by force if necessary, to a process of modernization and enlightenment. Tragically, this approach is hardly different from that of the tsarist regime which, as Groys notes, also justified the brutality of its rule over the peasants by claiming a “superior level of enlightenment compared to the still unenlightened Russian masses” so that “the Enlightenment was often associated in Russia with political violence and mechanisms of power.”8 The influence of Chernyshevsky’s novel was huge. The anarchist Peter Kropotkin called it “the banner of Russia’s youth,” who, having read it, went into the countryside in droves to make the peasants fit for revolution. The historian Figes even claims that this “dreadful novel” converted more people to the cause of revolution than all the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels put together (he also writes that Marx learned Russian specifically in order to read this book).9

In the realm of art, the role played in the revolutionary movement by Chernyshevsky’s novel was played by his treatise The Aesthetic Relations of Art to Reality, published in 1855. The author described the aims of the treatise as follows: “Defense of reality as against fantasy, the attempt to prove that works of art cannot possibly stand comparison with living reality—such is the essence of this essay.”10 With reference to Hegel, Chernyshevsky strictly rejected fantasy as misleading and the aesthetic category of beauty as harmful, concluding by declaring art to be superfluous. Only if it makes itself useful, he argued, can it attain legitimacy. “Art must show society which phenomena of reality are good and useful for it, calling for support and perpetuation, and which are too difficult and damaging, calling for them to be banned or at least toned down to render them useful.”11

Chernyshevsky’s utilitarian view of art was shared by a group of literary critics led by Nikolay Dobrolyubov and Vissarion Belinsky. Their supporters loved to shock the francophone salons of the big cities with slogans like “Boots are higher than Shakespeare” and by judging Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina as a “trifle whose value, if it has any, is purely gynecological.” Chernyshevsky’s followers also included a group of painters. They called themselves Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) on account of their habit of taking their pictures painted in the style of Western realism to villages to convert the peasants (who they depicted in typically French landscapes dressed in Western clothes) into revolutionaries. The group’s most prominent member was Ilya Repin, who referred to himself as one of the 1860s generation. The group was supported by Vladimir Stasov, the art critic at the influential St. Petersburg business newspaper Novosti i birževaja gazeta (News and Stock Exchange Paper). This may sound surprising, but in fact it corresponds precisely to the interests of a rapidly growing economy that depended on a constant influx of new “enlightened” workers from rural areas. While the Peredvizhniki were enjoying considerable success in the two major cities, they were not especially well received in the countryside; their struggle for knowledge frequently ended in brawls. As the artist Naum Gabo, who grew up in the countryside, recalls, the peasants rejected the pictures of the Peredvizhniki from the outset because they saw them as “exclusive” and “confined to the world of the ruling class.”12

Like the Peredvizhniki, most bringers of enlightenment were met with bitter resistance from the peasants who rightly saw their rigorous rationalism and militant atheism as a threat to the very structures on which their lives were based. Disappointed, the urban youth withdrew from the villages and their initial, blinding enthusiasm turned into a deeply contemptuous attitude. Reports about filthy poverty, primitive violence, intolerable alcoholism, and shameful backwardness appeared in the press—including supposedly authentic descriptions by the city-raised writer Maxim Gorky.

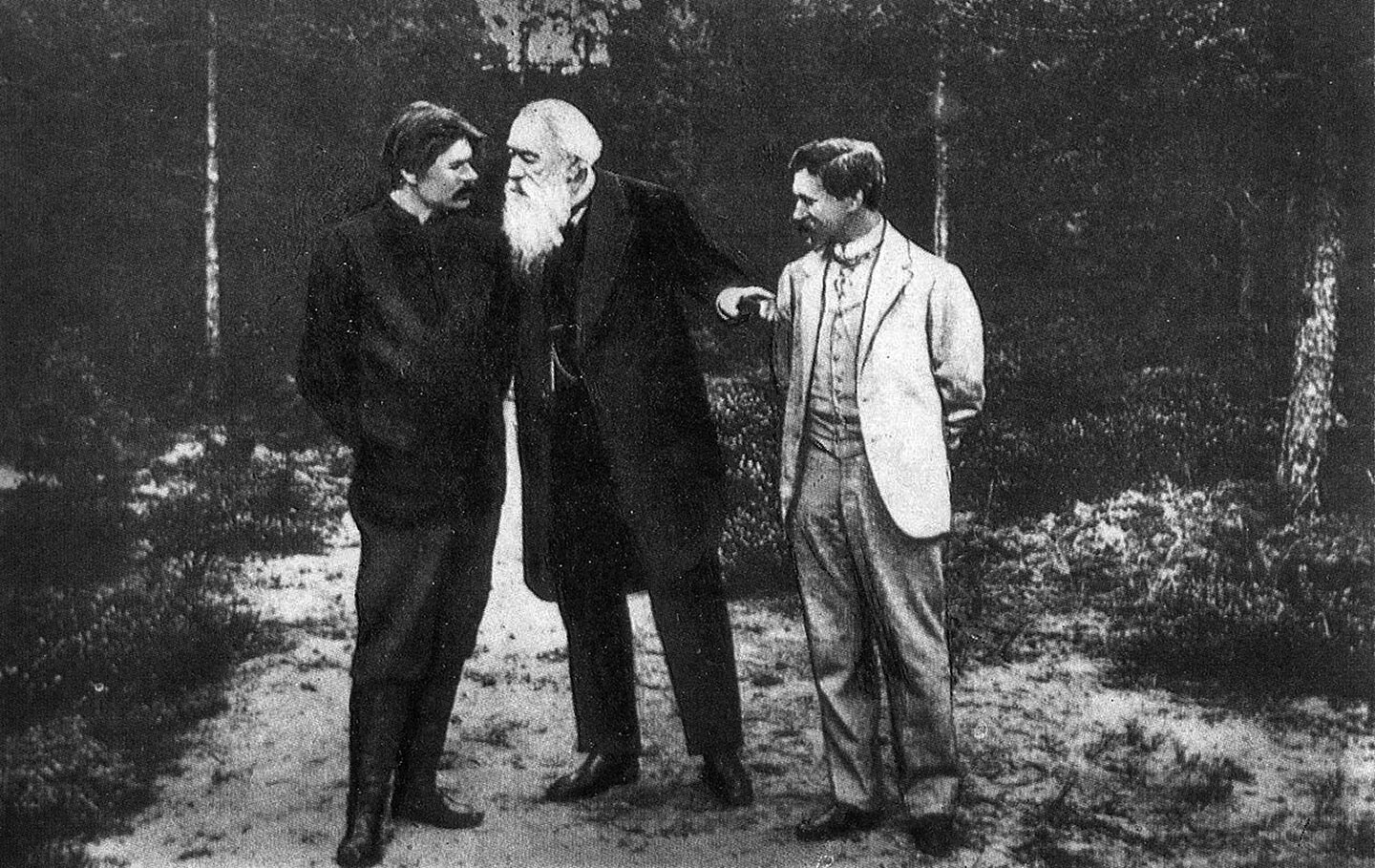

Photo of the so-called triumvirate of Maxim Gorky, Vladimir Stasov, and Ilya Repin (1905). In the early 1900s, the three were the most influential figures of official Russian culture.

At this point, having previously held the same views as the 1860s generation, Dostoyevsky began to have doubts about what was happening in the countryside: “Do you remember why the young Dostoyevsky was given the death sentence?” asked Nadezhda Tolokonnikova of the punk band Pussy Riot at her trial: “All he had done was to get carried away with socialist theories … At one of the last meetings, he read out Belinsky’s letter to Gogol, which was packed, according to the court, and, please note, ‘with childish utterances against the Orthodox Church and the supreme authorities.’”13 Dostoyevsky was sentenced to death, but as he stood before the firing squad he was pardoned and sent into exile, where his encounters with peasant life changed his attitude.

In 1861, having returned from his banishment, Dostoyevsky founded the magazine Vremja (Time). As Michel Eltchaninoff has stressed, his goal was to look for alternatives to the failed modernization measures of the intelligentsia.14 He began by publishing his novella Notes from the House of the Dead, an angry reckoning with Chernyshevsky’s purely rational and materialistic legitimation of human action. This prompted an essay by the critic Dobrolyubov who, with reference to Chernyshevsky, once again vilified traditional peasant culture as primitive, stupid, and an obstacle to progress. Dostoyevsky was furious, attacking Chernyshevsky’s aesthetic theory in a language of unprecedented severity as a “boundless stupidity” which, if not stopped, would have “calamitous” effects on the further development of Russian culture as a whole. “It is absurd to say,” he writes, “because this may be the opinion of some bookish scholar, that all these aspirations of the Russian spirit are useless, foolish, and unlawful.” And: “You cannot possibly satisfy a man who has a certain need for something by telling him ‘Oh no, I don’t want you to do that, I want you to live like this and not like that.”15

Dostoyevsky once again spoke in favor of the imagination, saying that even everyday life cannot be successfully tackled without it. And since art arises from everyday life, art without imagination is inconceivable—just as life, and with it art, are inconceivable without beauty, which he defended with words that became the motto of an entire generation after 1900: “Art is as much a necessity for man as eating and drinking … Man craves it, finds and accepts beauty without any conditions, just because it is beauty.”16 Twelve years later, in 1873, he visited an exhibition of work by the Peredvizhniki and found all that he had been warning against realized. This style of painting, he wrote, was hollow, stupid, superficial, and above all hypocritical, its tendentious interpretation of reality coming at the cost of any search for artistic truthfulness and human honesty. In Dostoyevsky’s view, anyone who has learned to shed tears over feigned suffering will be heedless of real suffering.17 This hypocritical realism of the Peredvizhniki is countered with a “higher realism” that he claims to find in the icons, songs, fairy tales, and legends of peasant tradition: “With full realism, to find the man in a man. This is primarily a Russian trait, and in this sense I am, of course, of the people.” He then refers to himself as “a realist in the higher sense.”18

For the rest of his life, Dostoyevsky railed against the widespread view of the Russian people as a tabula rasa just waiting to be reshaped into rational atheists based on the Western model, and he dreamed of Moscow as a third Rome that would have the power to resist the “modernizing mania” coming from Western Europe. As Mishra writes, Dostoyevsky was among the “latecomers to political and economic modernity … who sensed acutely both its irresistible temptation and its dangers.”19

Dostoyevsky was supported by Vladimir Solovyov, a “zealous materialist” who had previously thrown the icon out of his window. When he began to doubt his convictions, he enrolled at the seminar for Orthodox clergy at the Monastery of St. Sergius to study theology. In 1874, aged twenty-one, he submitted his dissertation to St. Petersburg University: entitled The Crisis of Western Philosophy: Against the Positivists, it made him famous overnight. In it, Solovyov first accuses Western thinking of failing metaphysics: rather than trusting in an all-permeating spirit, it looks for pseudo-rational explanations. Western thinking also fails epistemology because it emphasizes reason while ignoring “the subconscious,” by which Solovyov meant faith, dreams, the imagination, and creativity. In ethics, too, development had led Western philosophy to believe

that the ultimate goal and supreme happiness were to be sought in a community created by force through a worldwide process forming a single unity, destroying the self-assertions of both individual persons and separate spiritual communities, subsuming all into a community subject to the absolute spirit.20

With this critique, which anticipates postcolonial attacks on the hegemonic striving of modernity, Solovyov contested the legitimacy of the project of the Russian intelligentsia in “enlightening” the peasantry.

Four years later, he gave a lecture at St. Petersburg University in which he attempted to unite socialism and its Western-atheist orientation with the social teachings of the Russian Orthodox Church, thus opening up a route to social equality that would be compatible with Russia’s specific sociocultural conditions. It caused a sensation: close to a thousand people were in the hall, including the writers Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. It is said to be the only time the two of them were in the same room. But resistance was soon fomented by representatives of the intelligentsia. In an unprecedented press campaign, Solovyov was declared mentally ill and his lectures were disrupted by organized student mobs. Under this pressure, Solovyov resigned from his post as professor of philosophy.

He continued working on his concept of a new knowledge that sets itself the task of uniting “recent Western philosophy in its logical perfection” with “the form of faith and spiritual contemplation via the great theological teachings of the East.” In Russian, he used the term duchovnoe, meaning “the spiritual.” In 1884, he published a text outlining the concept under the title Duchovnye osnovy žizni (The Spiritual Fundaments of Life). In it, he predicts a new era when “philosophy will reach out to religion,” which he calls “the epoch of the spiritual.”

By this time, however, no one was listening to Solovyov anymore; by a kind of self-imposed censorship, his thinking, like Dostoyevsky’s warnings, had been squeezed out of the public debate. The cultural life of the two big cities was dominated by a kind of mimetic appropriation of Western culture, as represented by Repin as president of the St. Petersburg Art Academy, the newspaper critic Stasov, and the writer Gorky. The latter in particular advocated a radical turn toward the West because he doubted the value of Russia’s own traditions: “The East will destroy Russia, the West is its only salvation … Meanwhile, I’m convinced of the greatness, beauty, and usefulness of all that the intellect of Western Europe has brought forth.”21

Ilya Repin, Portrait of Emperor Nicholas II, 1895. Oil on canvas, 210 × 107 cm. The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Repin was an official portrait painter of the tsar.

But now a new generation began to make itself heard. Its mouthpiece was the magazine Mir iskusstva (The World of Art) published by Sergei Diaghilev, a loveable twenty-six-year-old eccentric who openly lived his homosexuality. Later he would become world famous as the director of the Ballets Russes. In the first issue of Mir iskusstva, Diaghilev immediately spelled out the agenda as follows: “We are a generation that thirsts for beauty.”22 There was also a clear reference to Dostoyevsky in his opposition to the condemnation of icons:

This is a fateful error and as long as deliberately constructed harmony, regal simplicity, and unique beauty of colors are not seen in Russia’s national art, there will no true art in our country. Just look at our true pride, the old times of Novgorod and Suzdal. What could be nobler and more harmonious?23

And like Dostoyevsky, he accused the Peredvizhniki of being “lackeys” of the Europeanized elite. The itinerant painters became hate figures for Diaghilev’s generation, a reputation so enduring that in his account of tendencies in Russian art for The Blue Rider Almanac published in Munich by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc in 1912, David Burliuk, a contemporary of Malevich’s, wrote: “It is known that the term ‘Wanderer’ is now used as invective.”24

In texts by poet Andrei Bely, the magazine also introduced its readers to Solovyov’s critique of rationalism and the hegemonic claims of modernism, and to his concept of the spiritual. Bely also brought Friedrich Nietzsche into the discussion, getting Lev Shestov’s essay “Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche” published in the magazine in 1900.25 In additon to such theoretical writings, Diaghilev published pictures of old Russian art objects alongside images of modern works, presenting them as equals. This broke with the hitherto unshakeable view in Russia that the old Russian traditions were embarrassingly inferior to modern works. In the second issue, Diaghilev included reproductions of pictures by the painter Mikhail Vrubel, declaring him the most important contemporary artist. Vrubel was the first painter to abandon Western realism and develop a style borrowing elements such as the construction of space from icon painting. But when he tried to show his pictures at the industry fair in Nizhny Novgorod in 1896, he provoked an uproar in the press led by Gorky. From then on, it was alleged, speaking his name aloud was enough to cause French-speaking ladies to faint.

The shock Diaghilev caused with his magazine was huge. Repin writes that it first rendered him speechless, before he began to fear for Russia’s reputation as a modern nation.26 Stasov spoke of “intellectual paupers” and an “orgy of debauchery and madness.”27 For many in the younger generation, by contrast, Diaghilev’s publication came as a revelation: “There is no other way of putting it: my life split into two parts—before and after Diaghilev. All of our notions about art, how we thought about it, were changed. It was like a light being switched on,” recalls Sergey Makovsky, who in 1909 founded the magazine Apollon, which became the mouthpiece of the artists Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Vladimir Tatlin, and Malevich. With his magazine, Diaghilev succeeded in making Solovyov’s concept of the spiritual so popular that his generation was derided by its enemies as the “generation of the spiritual.”

At the same time as Diaghilev, Sergei Bulgakov and Nikolai Berdyaev, both Marxists unsettled by their experience in the countryside, also discovered Solovyov, becoming active advocates of his thinking. As professor of political economy at Moscow University, one of Bulgakov’s students had been Kandinsky, who left Moscow in 1889 to study the administrative structures of peasant communities in the Vologda region. On his return, he wrote against the negative reports: “After the ‘emancipation’ of the serfs in Russia, the government gave them control of their own economy, which to the surprise of many people made the peasants politically mature.”28 It was these experiences of rural life that prompted Kandinsky to abandon academia and become an artist. In 1912, he published On The Spiritual in Art in Munich, a continuation of Solovyov’s philosophy, heralding a new epoch, the “age of the spiritual.” At the same time, while preparing The Blaue Reiter Almanac, he tried to secure a contribution from Bulgakov as a representative of the “Russian religious movement.” In 1903, Bulgakov had published From Marxism to Idealism, in which he declared materialism obsolete and argued in favor of a socialism based on Orthodox teachings. This essay, which went through several editions due to great demand, marked a reversal in the discussion carried on since Chernyshevsky concerning the paths taken by Russian culture.

Around this time, after 1912, things start happening very fast. Young people were going to the countryside again, this time to learn for themselves: “At present, there are also other signs of a cultural resurrection,” wrote the critic Georgy Chulkov, “as young artists are passionate to learn from folk artists: uniting the individual work and the creative work of the people in a common cause, they are looking for a new realism.”29 Diaghilev travelled the country in search of icons. The poets Bely and Blok began to collect folk sayings and incantations, publishing them in an anthology. The poet Velimir Khlebnikov experimented with words, turns of phrase, and rhythms that he found in the rural idiom. The composer Igor Stravinsky collected folk songs. Goncharova walked through Moscow dressed as a peasant woman and announced:

I shake the dust from my feet and leave the West, considering its vulgarizing significance trivial and insignificant—my path is toward the source of all arts, the East. The art of my country is incomparably more profound and important than anything I have known in the West.30

And in 1913, Apollon published an essay by the critic Nikolay Punin, a friend of Malevich and Tatlin, entitled “Puti sovremennovo iskusstva i russkaja ikonopis” (The Paths of Modern Art and Russian Icons), in which he subjects icon painting to a formal analysis because he believes “that the icons, in their grandiose and living beauty, will lead contemporary art to achievements that will differ critically from those experienced by European art in recent decades.”31 People were euphoric, talking about a “renaissance” of Russian culture, with Dostoyevsky and Solovyov considered as its prophets.

Conversely, increasing numbers of young people were coming into the cities, including Tatlin, a trained icon painter, and Malevich, who had grown up with icons in rural areas. Malevich’s first encounter with a realistically painted picture in Kiev came as a shock to him. He realized that there was a difference between art in Kiev, this art of the aristocrats but also of “revolutionary minded people,” and the art of the peasants. And he decided to remain “on the side of peasant art.”32 Around 1910, Malevich began painting peasants, borrowing from icon painting in terms of his construction of space and his use of lines, color, and light. In fact, Malevich painted peasants throughout his life, without scholars ever asking why.

Scholars have similarly ignored the contents of the manifestos written between 1910 and 1913 by Khlebnikov and the poet Aleksei Kruchenykh, in which Malevich also had a hand. They all testify to the shaping influence of Dostoyevsky and Solovyov on the thinking of these artists. The zaum movement, proclaimed in a manifesto written in 1913 by Khlebnikov, Kruchenykh, and Malevich entitled “O chudoženstvenych proizvedenijach“ (About Artistic Works), can also be traced back to these two thinkers. The word zaum translates as “beyond reason,” referring to Dostoyevsky’s assertion that “a work of high art” always develops “in the absence of reason,” and to Solovyov’s notion of cognition expanded to include “the subconscious”:33 “We have now come to reject reason,” writes Malevich.

We have rejected it because another is ripening within us that can, in comparison with that we have rejected, be called zaum and that also constitutes laws and possesses meaning. Only when we have realized this can our works be founded on a truly new, transrational law.34

Malevich also made paintings he referred to as zaum pictures: Lady at the Poster Column (1914), for example, shows, alongside figurative elements, two monochrome squares. It was these zaum pictures that immediately preceded The Black Square shown at the “Last Futurist Exhibition” of 1915, a painting accompanied by a manifesto entitled From Cubism to Suprematism, an allusion to Berdyaev’s From Marxism to Idealism, as Malevich’s book, too, proclaimed not just a new direction, but a paradigm shift, as the painter never tired of stressing.

Kasimir Malevich, Lady at the Poster Column, 1914. Oil on canvas.

From all of these facts—assuming one accepts them—it follows that the Russian movement must be viewed as an attempt to face the divide that had been steadily deepening since Peter the Great between the Western-educated elite and the peasants—the millions of peasants who Chernyshevsky and his followers sought to persuade, as Mishra puts it, “to renounce, and often to scorn, a world of the past” in order to become “modern” people.35 “It is commonly said,” Malevich writes,

that Tsar Peter deservedly came to be called “the Great” because he smashed a hole into the non-objective cube towards the West, throwing open a window to the light. I on the contrary accuse him of having destroyed unity by letting in a destructive culture, opening the window to a highly dubious and suspicious light.36

This movement, which led to nonfigurative paintings, should thus be viewed not as the consequence of a westernizing process of modernization, but as a sign of rebellion against that process and its hegemonic claims. Naum Gabo also saw it as a rebellion:

The non-objective ideology proclaimed by the Suprematists in 1915 is the consequence of the rejection of Cubist experiments, but an art historian will not fail to see the real and complete influence that the concept of the Russian—of the icons as well as of Vrubel—had on the mentality and conscious vision of that group of artists in Russia.37

And Malevich is clearer still: “Historical materialism must be just as firmly rejected as subject matter in art!”38 In the 1920s, he wrote the following dedication in a copy of his 1920 essay “God Is Not Cast Down” for the absurdist poet Daniil Kharms: “Go and stop progress.”

Lenin, an admirer of Chernyshevsky, who wrote a 1902 book with the same title as Chernyshevsky’s notorious novel, was alarmed, and in 1915 he commissioned Gorky to found the magazine Letopis (Yearbook). In the very first issue, Gorky declared the entire cultural development of the past fifteen years, whose beginning coincided for him with the inauspicious arrival of Diaghilev on the scene, to have been a disgraceful demise of Russian culture as a whole, a development that must be countered at last with a return to “heroic” art. And the second issue showed what he meant by this: it was devoted to the painter Repin. Two years later came the October Revolution and in December 1920 the newspaper Pravda published a letter from the Central Committee of the Communist Party condemning the artists of this movement as “decadents, supportive of an idealistic philosophy hostile to Marxism.”39 In 1925, the critic Punin, a companion of Malevich and Tatlin, wrote in his journal: “How we were all ruined, will it ever be understood?”40

According to Berdyaev, the October Revolution became

a sign of the nihilist enlightenment of materialism, utilitarianism, and atheism. Solovyov was entirely overshadowed by Chernyshevsky. The typical divide in Russian history that had been opening up throughout the nineteenth century between the intellectual cultural class and the broader, less formally educated masses, a divide which continued to deepen, meant that the Russian cultural renaissance plunged itself into this chasm.41

This fall heralded the end of a movement which with hindsight, in a view sharpened by postcolonial theorists like Said and Mishra, must be viewed as an emancipatory one. It was one of the first to dare to challenge the hegemonic claims of modernity. The fact that it was the October Revolution that put an end to it is among the great absurdities in the history of the twentieth century.

Thierry de Duve, “Don’t Shoot the Messenger,” Artforum, November 2013, 265.

Quoted in Pankaj Mishra, The Age of Anger (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017), 143.

Quoted in Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy (Penguin: London 1996/2017), 54.

Boris Groys, Die Erfindung Russlands (Munich: Hanser, 1995), 25.

Figes, People’s Tragedy, 89.

Ibid., 126.

See Mishra, Age of Anger, 68; and Figes, People’s Tragedy, 123.

Groys, Erfindung Russlands, 26.

Figes, People’s Tragedy, 130.

Nikolay Chernyshevsky, “The Aesthetic Relations of Art to Reality,” in Russian Philosophy Volume II, eds. James M. Edie, James Scanlan, and Mary-Barbara Zeldin (Chicago: Quadrangle Books 1965), 27.

Chernyshevsky, “The Aesthetic Relations of Art to Reality,” quoted here in Geschichte der russischen Kunst, ed. Nikolai Maskovcev (Moscow, Dresden, 1975), 257. (This passage is not in the published English translation.)

Naum Gabo, Of Divers Arts (New York: Faber, 1962), 147.

Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, closing statements from trial of August 8, 2012 →.

M. Eltchaninoff, In Putins Kopf. Die Philosophie eines lumpenreinen Demokraten (Stuttgart, 2016), 119.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, “Mr. G.- bov and the Question of Art,” in Occasional Writings (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1997), 132, 131.

Ibid., 124. Italics in original.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, “A Propos of the Exhibition,” in A Writer’s Diary Vol. 1: 1873–1876 (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1994), 205–16.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, diary entry from 1881.

Mishra, Age of Anger, 68.

Vladimir Solovyov, The Crisis of Western Philosophy: Against the Positivists (Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Books, 1996), 149. (Translation altered to reflect the meaning of the original Russian, as reflected in the author’s translation into German.)

Quoted in Geir Kjetsaa, Maxim Gorki (Hildesheim, 1996), 231.

Sergei Diaghilev, “Osnovy chudožestvenoj ocenki” (The Foundations for Artistic Evaluation), Mir iskusstva 1 (1898): 60.

Ibid., 58ff.

David Burliuk, “The ‘Savages’ of Russia,” in The Blaue Reiter Almanac (New York: MFA Publications, 1989), 75.

Lev Shestov, “Dostoevskij i Nitse,” Mir iskusstva 7 and 8 (1900). See also Lev Shestov, “Dostoevsky and Nietzsche,” in Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Nietzsche (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1969).

Ilya Repin, “Po adresu ‘Mira iskusstva,’” reprinted in Mir iskusstva 10 (1899).

Vladimir Stasov, “Chudye duchom,” Novosti i birževaja gazeta, January 1, 1899.

Wassily Kandinsky, “Reminiscences,” Complete Writings on Art (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994), 362.

Georgy Chulkov, Pokryvalo izidy. Kritičeskie očerky (Moscow 1909), 77.

Natalya Goncharova, “Preface to catalogue of one-man exhibition, 1913,” in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde, Theory and Criticism, 1902–1934, ed. John Bowlt (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1976), 57–58.

Nikolay Punin, “Puti sovremennovo iskusstva i russkaja ikonopis,” Apollon 10 (1913), 50.

“Kazimira Maleviča. Glavy iz avtobiografii chudožnika,” in Kistorii russkogo avantgarda (Stockholm 1976), 108, 118.

See also Aleksei Kruchenykh, Ivan Klyun, Kazimir Malevich, “Tajnye poroki akademikov” (Secret Vices of the Academicians), Moscow 1915. Here, too, the authors refer directly to Dostoyevsky.

Letter to Matyushin, 1913, in Sieg über die Sonne, exhibition catalogue (Berlin 1983), 39.

Mishra, Age of Anger, 155.

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematismus—die gegenstandslose Welt (Cologne 1962), 99. (Translated from the German by NG, as this passage doesn’t appear in the published English version, The Non-Objective World: A Manifesto of Suprematism.)

Gabo, Of Diverse Arts, 172.

Malevich, Suprematismus—Die gegenstandslose Welt, 98.

Natalia Murray, The Unsung Hero of the Russian Avant-Garde (Boston: Brill, 2012), 124.

Quoted in ibid., 194.

Nikolay Berdyaev, Vlastni životopis (Olomouc, 2005), 202.

Translated from the German by Nicholas Grindell.