That big, big beautiful plant behind us, which will be even more beautiful in about seven months from now … about 1,100 jobs and by the way, that number is going to go up very substantially as they expand this area.

— President-elect Donald Trump speaking at the Carrier plant in Indianapolis, December 1, 2016

When American President Donald Trump pays lip service to Western reindustrialization at a giant heating and cooling factory in Indianapolis, Indiana, we might ask whether we are living in a “postindustrial” era to begin with. Twenty-first century postindustry seems to bear little resemblance to the way the anarchist and historian of Indian art Ananda Coomaraswamy first imagined it a century ago.1 In 1914, drawing together Arts and Crafts, theosophist, and Swadeshi visions, he foresaw a postindustrial epoch blooming upon the demise of colonization across Asia and the derailment of industrialization in the West. In their stead, semi-literate artisans would resume medieval Sinhalese craft traditions, weaving together a precolonial social order unraveled by the incursions of the British Empire.2

Postindustrialism meant “permanent revolution”;3 communities of skilled artisans, drawing on their “intellectual and imaginative forces,” would supersede industrial capitalism from within.4 As Coomaraswamy imagined, this kind of community “would appoint as its servants, for life or good conduct, its craftsmen and its artists, just as it now appoints its judges, its preachers, its professors, and medical officers.”5 Rather than take up these appointments, however, craftsmen would exercise what he called “a spontaneous anarchy of renunciation,” a “repudiation of the will to govern.”6 Craft, fully integrated into spiritual practices, would constitute the fabric of a “social-corporatist” cosmopolitanism the world over, based on “mutual aid” and the recognition of common interests. The only limit to artisans freely exercising their species-being would be their ability to modify and manipulate their machinery.

By mid-century—in the wake of sociologist Daniel Bell’s 1962 rereading of the term—Coomaraswamy’s postindustrialism was all but forgotten. Dismissing his predecessor in a footnote, Bell prophesized that a fast-arriving post-ideological information society, not the craft guilds, would render industrialization obsolete.7 Never mind seizing the means of production, Bell’s smoothly functioning technocratic knowledge economy promised to erase class conflict altogether beneath the whirr of data processors coordinated by a centralized bureaucracy. Although the fantasy he envisioned likewise never came to pass, over the past three decades, defenders and detractors of neoliberalism have cemented his way of understanding globalization as a core composed of service-sector dominated “communicative capitalism,” “the new economy,” and “immaterial labor,” while agricultural and industrial labor are outsourced to the world periphery.8

Today, the two seemingly incompatible postindustrial paradigms of the twentieth century—Coomaraswamy’s social corporatism and Bell’s proto-neoliberalism—have improbably intertwined. Contemporary labor theorists echo Bell, noting how customization deindustrializes production and consumption, creating interdependencies among the once distinct domains where goods circulate. On the production side, computer-aided manufacturing and distribution monitoring facilitate just-in-time, bespoke goods and services, where self-correcting feedback loops help avoid oversupplying or undersupplying market demand. Meanwhile, Coomaraswamy’s unity of worker and machine has resurfaced, as user-generated, crowd-sourced, and personalized content displaces onto the consumer the duty of developing and reproducing commodities. This displacement allows corporations that facilitate these interchanges to vertically integrate cycles of research and development, production, marketing, and distribution, all while outsourcing each of these tasks to the lowest bidding subcontractor.

With the aid of Bell’s technocracy, an arch version of Coomaraswamy’s social-corporatism has come to pass. Karl Marx’s dictum that “necessary labor time” will be measured by “the needs of the social individual,”9 that “the development of the power of social production will grow so rapidly that … disposable time will grow for all,” may today be read with irony: rather than pointing to new forms of collective life, the growth of phatic or social infrastructures heralds less the coming of “socialism” than the commoditization of attention bartered across online media.10

This exchange transpires, above all, within a marketplace where corporate consultants, producers of digital content, and members of the creative industries compete and collaborate to define emerging lifestyle registers. By “lifestyle” I refer to the context where the routines of domestic life are transposed and presented back to persons who engage in them; similarly, “lifestyle register” is the performed combination of gestural, graphic, and spoken language appropriate to and entailing the “lifestyle” context. In retail, for instance, marketers brand commodities so they may confer value onto consumers, who in turn emblematize their distinction by purchasing, displaying, using, and interacting with these goods and services. Graphic designers advertising for Subaru create “bokeh effects” (the use of minimal depths of field to yield blurred backgrounds) so that the company’s self-conception as a zero-emissions manufacturer conforms to a prestige lifestyle register we might call “environmentalese.” In turn, people from their target markets drive hatchbacks and chat with each other about MPG rates and their trips to the outdoors. As marketers and consumers perform the lifestyle register appropriately, they collectively fix and stratify the value of the Subaru brand.

Asha Schechter, Coffee Scene, 2015. 13’57”, digital video. In this scene Babinski presents before the SGA Barista Championship judges.

The Artisanal Lifestyle Register

One of the most prominent lifestyle registers turns out to be the very one that preoccupied Coomaraswamy to begin with: the “artisanal,” witnessed today in trends towards eco-urbanism and design, small-batch fermentation and slow food preparation, industrial chic, upcycling, and other craft processes. Within the hermeneutic of ideology critique, these trends might index a return of the repressed, attempts to nostalgically recall residual labor processes sent to the Global South. The ubiquitous jargon of “sustainability,” for instance, seems to de-implicate individuals in systems of unequal exchange, resolving these systemic problems through a sympathetic magic within “self-governance” and “responsibilization” routines.11 Rituals around “ethical consumption” help individuals cope on a somatic level with their involvement in what Andre Gunder Frank once called “the development of underdevelopment,” where involvement can be masked and metonymized under a bioethic of self-care.12

These compensatory impulses should not be merely dismissed or psychologized as bad faith, nor condemned as a refusal to confront a totalizing neoliberal agenda. Rather, they speak to a peculiar fetishistic quality of contemporary life where we hypostasize concrete material contradictions within geopolitical systems through felt experiences with tangible goods and activities. Recognizing how these goods and activities are pictured by “creative industry” professionals, who materialize and make them available for publics at different scales, may help us understand how we go on to use them to displace risks, contradictions, and responsibilities onto ourselves. By looking at the agents and institutions behind these operations, we may move away from too-ready self-entrapment tropes around the “culture industry,” “consumer capitalism,” and “distinction,” and towards a more fine-grained account of how lifestyle registers hypostasize experience.

As Joanna Cook has persuasively argued in her work on the role that “mindfulness” plays under British austerity, ideology critique only considers “top-down intervention and does not account for diversity in the motivations … and efforts of people practicing self-governance and the collaborative nature of the political processes by which it is promoted.”13 Cook suggests that it is “the maintenance of diverse and multiple meanings around self-governance” that ultimately drives the “motor of the political process.” Register maintenance is key here. In order to understand the trend toward the artisanal—which seems to go hand in hand with the mindfulness and meditation Cook discusses—we must look at the compromises, alliances, and border maintenance that agents and institutions arrange with one another as they contribute to the stylization and diffusion of the artisanal register.

Over the past decade, the art of Asha Schechter has examined our collective management of the artisanal lifestyle register, often in online, short-form narrative documentaries. This increasingly popular medium—approximately three to seven minutes in length, and available for uploading, embedding, and streaming—puts on display the competition over the voicing and visualization of the artisanal register. As opposed to high-cost music videos and extended commercial film trailers—where production quality for the most part still lies in the hands of ladder guilds—short-form lifestyle videos involve minimal in-camera or postproduction editing and require only a do-it-yourself knowledge of audio and design software. This deskilled format contrasts with the belabored care and maintenance procedures depicted on screen—curing butter, pickling radishes, and related craft behaviors.14

Even as they diagram the consolidation of the artisanal lifestyle, Schechter’s videos toe the line between describing these processes and nominating themselves as token instances of the type. Schechter brings in other “creatives” to act as characters on screen; the works circulate on the same blogs and video-hosting services, such as YouTube and Vimeo; and they employ many of the same tropes, edits, and effects found in how-to videos about the mental-health benefits of drinking La Croix sparkling water or in Photoshop tutorials where novices learn to create bokeh effects. Meanwhile, commercial magazines occasionally hire Schechter as a “picture researcher” to discover these effects within a stock of images, which they go on to pair with their own publication content. Even as his videos contribute to the very formation of variables that make up the artisanal register, their existence as art objects flirts with a counterhegemonic position by revealing the parallel labor processes that naturalize the lifestyle.

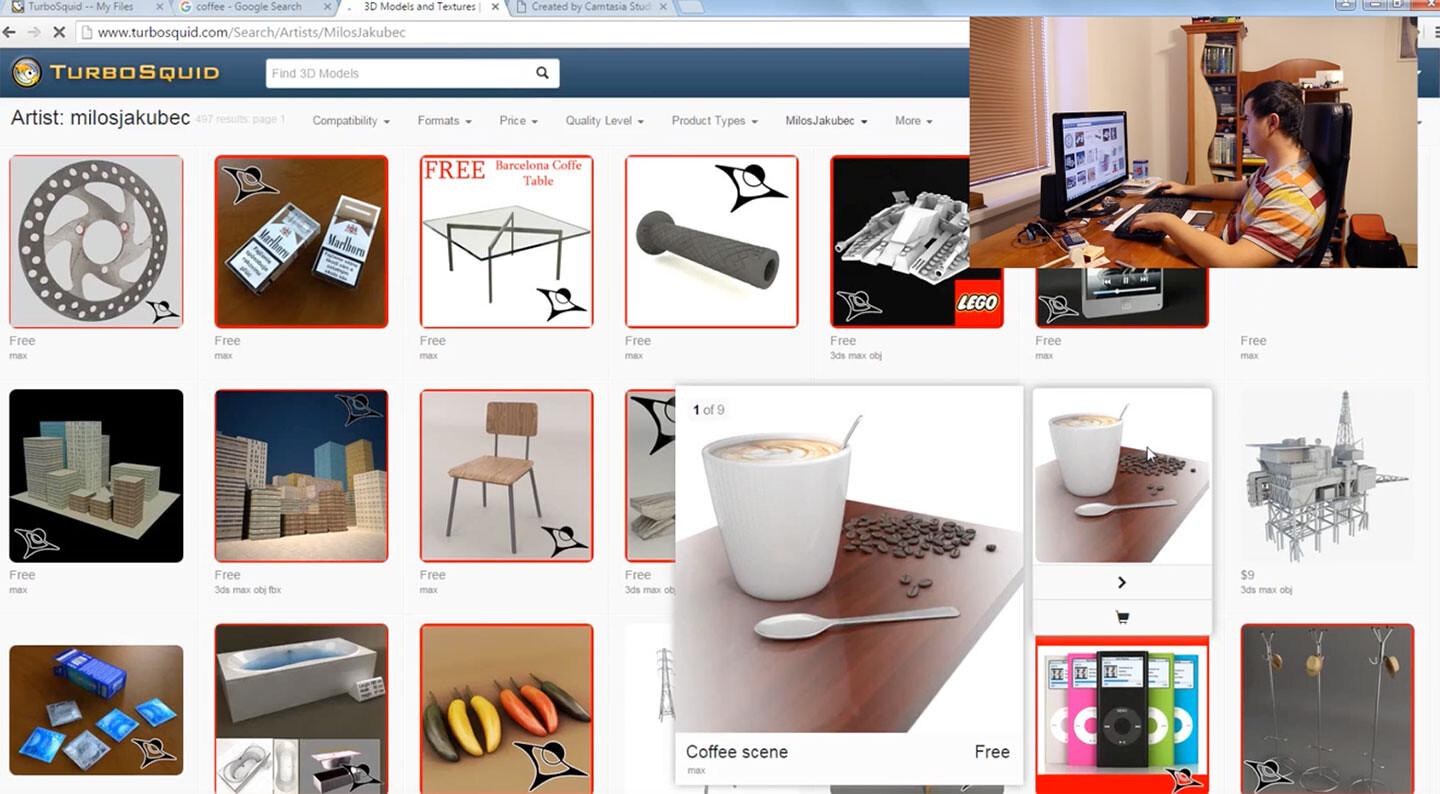

Asha Schechter, Coffee Scene, 2015. 13’57”, digital video. In this shot Jakubec uploads the digital rendering onto Turbo Squid.

Asha Schechter’s Coffee Scene

Schechter’s Coffee Scene (2015) considers the way artisanal lifestyle variables are produced, discussed, and replicated to instantiate registers of conduct, which is part of the artist’s larger project around renovating avant-garde strategies associated with productivism. The video opens on the sidelines of the 2015 US Barista Championship, an event sponsored by the Barista Guild of America (BGA) and the Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA), institutions offering aspirational baristas skill-building workshops, certificate programs, tasting sessions, and seminars on “coffee technology and innovation,” without the dues and bargaining power involved in traditional trade unionism. As nonantagonistic post-Taylorist alliances, the BGA and the SCAA standardize professional practices around the provisioning of coffee services, teaching individual baristas to develop a specialty lingo of refinement and connoisseurship while learning the ins and outs of latte art. Workers are trained so that their own gestures, talk, and beverages conform to an increasingly regimented performance of service.

Schechter’s service-Olympics protagonist in Coffee Scene is Charles Babinski. A bearded millennial with an apron and a printed cotton sports shirt rolled up to his elbows, he resembles just the kind of early-twentieth-century postindustrial artisan Coomaraswamy once imagined. In the initial shot, Babinski carefully sets up a tableau of stainless steel frothing pitchers, butcher-block tasting platforms, and ceramic espresso cups for yet-to-be-seated “sensory” and “technical” judges. But just as the video begins to settle comfortably into offering a behind-the-scenes account of Babinski’s calculated conduct, Schechter cuts to 3-D digital modeler Milos Jakubec sitting alone at a home-office workstation in an unnamed Slovakian village. Jakubec plays Babinski’s antiheroic double, narrating as he renders a three-dimensional model of a cappuccino, the very drink Babinski will soon produce for the competition judges.

The video allows the two protagonists’ contradictory forms of coffee expertise to intersect. Jakubec’s clicks of the mouse and scroll of the cursor are regulated by the preestablished protocols of imaging software and take place within the frame of the computer screen, contrasting with Babinski’s machine-age pouring of the milk, control of steam, and turn of the nobs. Through a portable PA microphone, Babinski’s hyper-articulate, scripted voice tells the judges that he is “really excited to be here today.” Meanwhile, Jakubec narrates his navigation through layers of superimposed images in a thick Slovakian accent devoid of grammatical articles: “now I must create plane,” “now I make layer.” Babinski’s speech is accompanied by moderately paced house music, Jakubec’s by melodic hardcore playing through his tinny computer speakers.

Babinski uses juniper spice to create precious complexity, while Jakubec remarks that he is glad he doesn’t have to deal with the “simulation of liquids.” Babinski sprays pressurized water and milk through a phallic nozzle to create microbubbles of aphroditic foam; Jakubec creates a similar effect by inserting digital noise around a flat surface rendering. Babinski describes the “personal” connections he makes with his customers as a small-business owner; Jakubec claims, “I don’t need fake reality, but I have reality in this software.” Babinski gives an impassioned speech about the sustainable business practices he maintains with “my farmer in Honduras,” which is greeted with audience applause; Jakubec describes how he can publish his CGI cappuccino anonymously on TurboSquid, an online marketplace for 3-D models, where it will be purchased by art directors and animators and inserted into projects and advertisements on which he has no input. We witness a back-and-forth dance between two diametrically opposed projects, Babinski’s revolving around his expert management of his own gestures and utterances, Jakubec’s around the speed and verisimilitude with which he makes the digital cappuccino.

Placing the two side by side, Coffee Scene asks: How separate are the different nodes of freelance economy occupied by Babinski and Jakubec? How proprietary are their skills to their social roles? How strict is the division between service and graphic design, between the management of the gestural and the visual, and where do the two coincide?

When Babinski, with bated breath, utters “my farmer in Honduras” or “hint of juniper,” he is branding aspects of his speech, turning his terminology itself into a lifestyle variable, not unlike the physical cappuccino he makes with the turn of his hand and the pour of his wrist. Both the commodity and its associated rituals index distinction around Babinski’s person, defining him iconically as an upwardly mobile authority, a well-trained maven—like his coffee, a person of considerable “complexity.” He is socializing his gestures and speech into “oinoglossia,” the register through which we linguistically produce prestige comestibles: “ice cream, olive oil, vodka, etc. … all those things that through artisanal labor represent nature turned into culture,” as Michael Silverstein writes.15 Coffee is no exception. As coffee becomes aggressively marketed to wider social domains, speaking about its powers and effects in an appropriate manner produces new images of normativity. Coffee talk “seize[s] the imagination of a wide sector of people anxious about social mobility” so that “educated connoisseurship can be manifested while doing away with the artifact of perceptual encounter”—that is, with the coffee itself. Schechter emphasizes the construction of these images of refinement by showing how the judges swill their drinks in the manner of a sommelier, as a commentator analyzes the intricacies of Babinski’s performance. This is not merely a taste test: the wider focus is on the way baristas manage face, that is, the impression they make on the judges and general audience.

Schechter’s barista-as-sommelier plays into a process that Silverstein has described as register “emanation.” Emanation is the “radiation of cultural signification” whereby “centers of value production” “anchor [the] trajectories of circulation” of a given lifestyle.16 When marketers, connoisseurs, and ordinary consumers talk about coffee, they are really doing two things simultaneously. They are talking about the quality of the bean at the same time that they index the social identity of the speaker as the type of person who engages in coffee talk. This second indexical function produces a “register effect” that allows the register to spread, or “emanate,” across separate events. By employing these register effects, the speaker constructs and classifies prestige and attributes it metonymically to what surrounds them, whether it is the granite countertop that supports the espresso cup or the high-tech dishwasher that cleans up afterwards.

The way in which those who provision, discuss, and consume coffee accrue and emanate Bourdieuian distinction is fairly intuitive to anyone who has lived through the diffusion of the Starbucks brand from Seattle-based upscale cafe in the 1990s to the interstate rest-stop parody fodder of today. But the way in which the linguistic production of lifestyle variables emerges dialectically with co-occurring visual and material cues is less easy to discern. It is not altogether clear how our expectations around speaking about comestibles align qualitatively with our tastes for them, or the images we create around them. Coffee Scene asks how oinoglossic fashions of speaking work co-constitutively with the management and manipulation of visual images that seem to do the same thing. How, in other words, do the commoditization of textual and visual emblems go hand in hand?

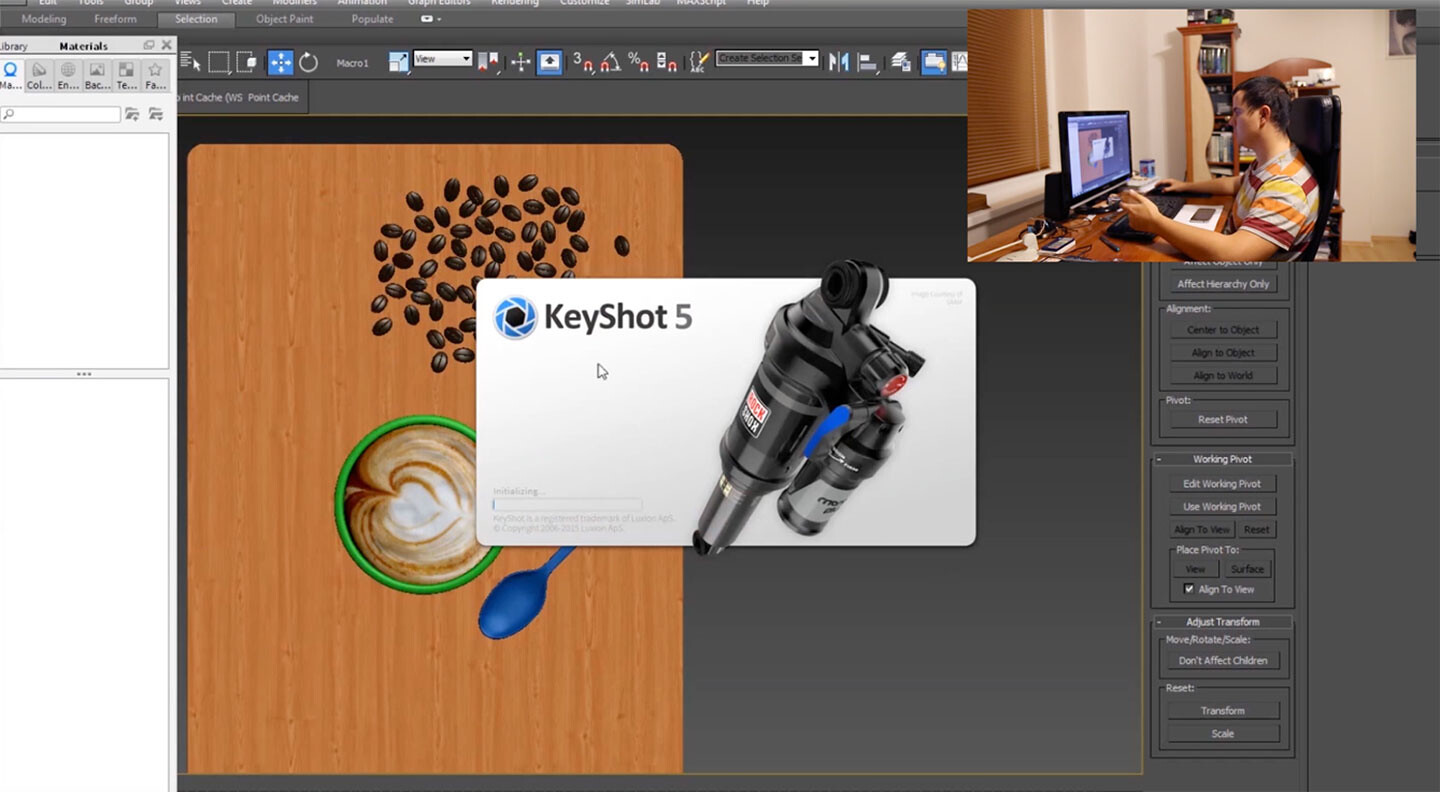

By placing the dual processes of linguistic and visual production side by side—Babinski at the counter, Jakubec at the computer—Schechter invites us to look more closely at the material dimensions of semiosis, that is, at how the winning cup of cappuccino emerges simultaneously within the constraints of both digital editing protocols and physical comportment. The elements taken for granted in one context become the site of scrutiny and virtuosic performance in another. The glint of porcelain, the sheen of the stainless-steel pitcher, the brushed-metal espresso machine merely serve as the shiny backdrop for Babinski’s foreground theatrics. But for Jakubec, the management of these reflections from cup to saucer, or the satin opacity of the coffee bean, is the bread and butter of visual editing. Inversely, the way Babinski creates “complexity” around his drink through his baroque explanations of provenance and his secret insertions of flavors becomes literally flattened out in Jakubec’s concern over surface effects—creating accurately modeled planes and layers across compatible software such as 3ds Max and KeyShot 5.

Asha Schechter, Coffee Scene, 2015. 13’57”, digital video. In this scene Jakubec moves the image into KeyShot 5 in order to manage the reflections and textures of the cup and spoon.

Freelance Productivism

The complementarity of Jakubec and Babinski’s projects presents us with a kind of post-productivist, Vertovian simultaneity. It reveals isomorphic similarities in the rhythms of seemingly diverse workflows, a bridge between working with pictures and picturing work. Like many members of the Russian avant-garde in the decades following the 1917 revolution, Dziga Vertov wanted to articulate how cultural forms—film in his case—incarnated the motions of factory work. His filmic isomorphisms emplotted the exposure, production, editing, and projection of film into other spheres of labor. The paradigmatic Elizaveta Svilova editing scene from Man with a Movie Camera (1929), for instance, begins with a solitary woman sewing fabric by hand. Then this activity becomes mechanized and several more seamstresses appear. It turns into a social activity—the seamstresses seem to be in a lively state of camaraderie as the wheels of the machine spin next to their smiling faces. But what initially seems like a representation of work becomes an analogue to it. As the fabric moves through a sewing machine, the sewing needle penetrates and binds the fabric at the moment where the light hits it, which turns out to be a structural analogue for the way the film projector takes up celluloid through its sprockets as the light that hits the back of the film binds the image to the screen. The technology of sewing develops out of the gesture of the hand, and in turn, the apparatus of the film projector finds its vestigial skeleton in the work of the sewing machine.

This analogy is meant to function pedagogically.17 Through the equivalency it sets up between tangible fabric and celluloid, Vertov assigns utility to the filmstrip, inserting it into relations of material production. In turn, the audience is provoked to discover structural similarities between the movement of one object and its filmic equivalent. The sequence makes the case, as Jonathan Beller writes, that “the image is constituted like an object—it is assembled piece by piece like a commodity moving through the intervals of production—and it is a technological and economic development of relations of production.”18 Insofar as the sequence discovers the technological origins and development of the projector in the sewing machine, Vertov reconciles or familiarizes the collective audience’s encounter with new equipment. What might be an otherwise alienating relationship for the public is made visible both historically and materially in the surrogate sphere of the cinema.19 In this manner, the work on screen and the work on the image prefigure the shared activity that might burgeon in Soviet collective life.20 His montaged intervals bind a particular movement or gesture to a constellation of productive labor forces, offering up a total view for the collective audience of themselves and their shared project of communization.

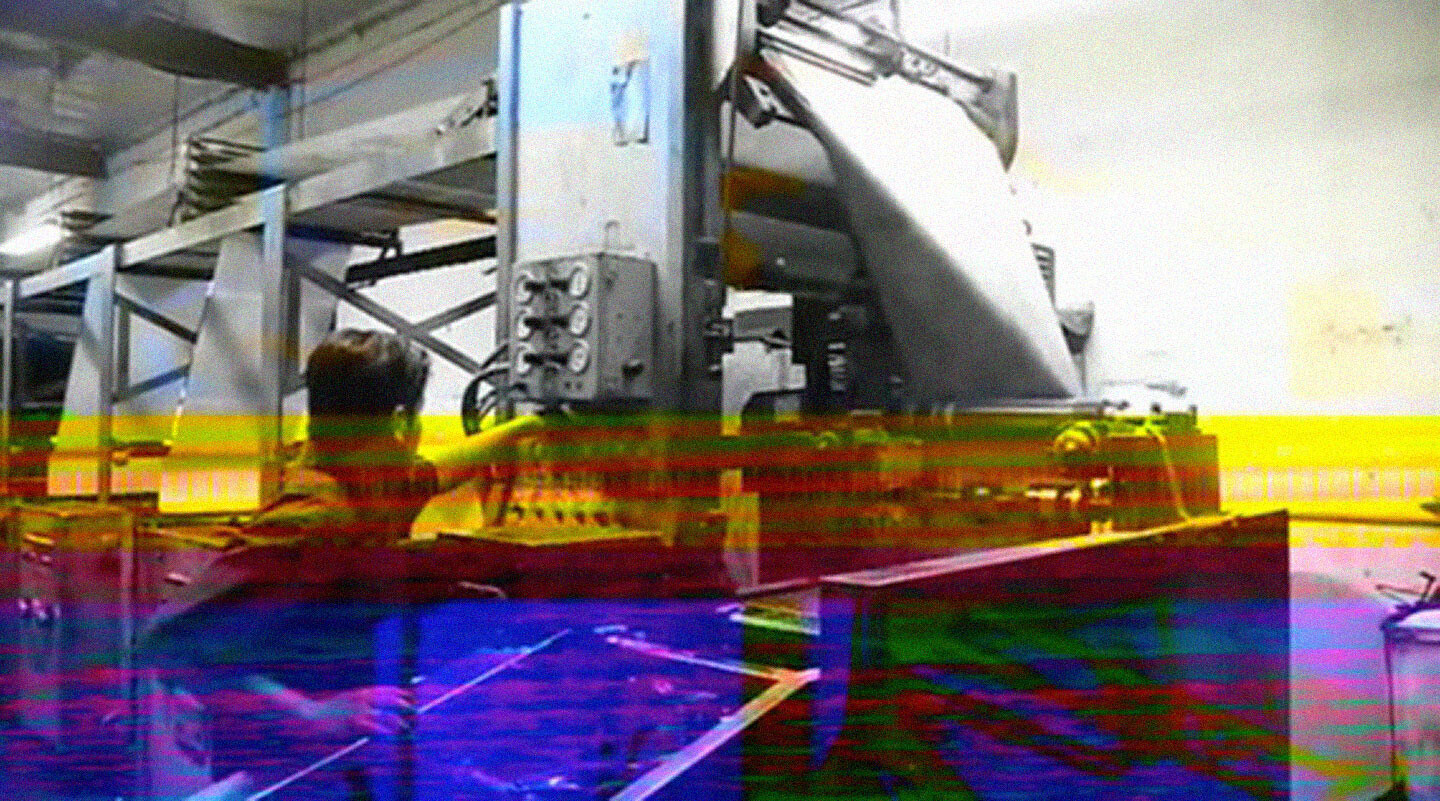

Asha Schechter, Newspaper Factory, 2010. 1’02”, digital video.

Where Schechter’s earliest videos showed newspapers he had designed roll off the presses—in the manner of Pravda issues in Man with a Movie Camera—his more recent productivist montages present isomorphisms within segmented pockets of freelance labor, where providing digital editing services in Slovakia never quite links up with serving cappuccinos in Silverlake. Unlike the Kinoks—the alliance of factographic filmmakers around Vertov—the BGA and SCAA hardly provide any material or collective benefit for baristas, but just a kind of associational style or branded uniformity. Thus, the commonalities that do exist between Babinski and Jakubec are hardly affirmative. Their parallel masturbatory fidgeting with mechanical knobs and keystrokes hardly belies a factographic utopia, but rather their contemporary proletarianization: the extent to which they make their working behavior conform to the demands of flexibility in the new service economy.

Nevertheless, Coffee Scene does make labor processes visible at disparate moments around the chain of semiosis through which commodities like coffee circulate. We are reminded again of Coomaraswamy’s anarchist cosmopolitanism based on the “recognition of common interests” in the absence of a regulating governing body. Even if Coffee Scene does not present a rhythmic simultaneity of undivided collective experience back to the collective—as Vertov had intended—the video does prompt dispersed freelance workers to mutually recognize their divergent forms of expertise. In doing so, Schechter begins to picture the range of service-economy requirements for freelancers who become socialized into the artisanal register by disparate ways and means.

Schechter’s montages, camera angles, and explicit commentary on the construction of images seem likewise distantly connected to the “industrial reflexivity” and “industrial allegory” that film theorists have outlined in recent years.21 John Caldwell observes that “any screenplay or project developed … today generates considerable attention and involvement … by personnel from the firm’s financing, marketing, coproduction, and distribution, merchandizing, and new media departments.”22 This “attention and involvement” finds its way on-screen through a set of reflexive genres that “out” the “embedded production knowledge” of the industry. Through regular “public disclosures to the viewing audience,” Hollywood manifests the contradictions among its unions, corporations, and workers through its products.23

If Vertov’s isomorphisms and Hollywood-studio reflexivity have facilitated the emanation of the industrial register to different ends, how do Schechter’s work within the current economy? Schechter’s videos—and the innumerable lifestyles on which they operate—are neither directed at mass audiences nor produced by professionals from the film and television industry, even in Hollywood’s recent, flexibly specialized post-studio phase, where many workers occupy a precarious position with regard to the projects they help make. Rather. Coffee Scene is emblematic of a new periphery of prosumer para-professionals: namely, producers of digital content, marginal members of the “creative industries” who circulate content exclusively online. Their videos—even when tied to a corporate branding initiative—are often explicitly didactic, circulating as visual manuals for audiences who may be motivated to realize their own DIY artisanal projects, in turn filming them and uploading their own videos.

Coffee Scene, alongside Schechter’s numerous other videos and photographic projects, provides a compendium of generic devices and effects drawn on by the heterogeneous group of amateurs, artists, and others who upload content. They show how “creatives” employ these devices and effects in nonuniform ways, accessing the artisanal register with different competencies and motivations. How, for instance, does the job of a buyer who needs to assemble the materials for an exposed brick display for the Home Depot website differ from a commercial photographer who is looking to shoot a loft for the background of a J. Crew catalogue, or an art director location-scouting for a reboot of Wall Street? Rather than reify these like-minded processes in the thing, in the exposed brick itself—which has been the pitfall of so much “speculative materialist” commodity fetishist art of the past half decade—Schechter assembles the conflicting and congruent orientations of freelancers in these processes.24

In consequence, his approach reveals how a philosophical program like object-oriented ontology—which imagines objects as void of human apprehension and social semiosis—actually ends up assimilating lifestyle registers into contemporary art. Observe the pervasive use of consumables, self-care products, fitness equipment, and bodies as raw material in recent years. By “extracting” these objects from the multiple social paths they travel, rather than addressing the processes of their circulation, artists are able to picture only their own participation in and knowledge of these lifestyle tokens. By melting rubber gym mats and bricolaging otaku-style prostheses, they demonstrate their facility with the conventions of “transhumanism”; by holding yoga-happenings and culinary workshops in gallery spaces, they present themselves as competently artisanal. Each token of a register type is meant to orient towards and outflank others within a field of artistic lifestyle production.25

If Schechter’s work takes part in the legacy of productivism and polemics around the “postindustrial,” it is because it evidences the struggle among freelancers over the artisanal register itself—the war of position taking place over its standards of appropriateness as they become increasingly codified. As his video reveals, the register rigidifies at points of intersecting commoditization across language, services, and goods, where the process of exposing live yogurt cultures to the right amount of light and air aligns with the exposure rates and lighting conditions of the amateur food photography used to document this very process. In this way, Schechter presents the dialectic through which people working in diverse fields and levels of professionalization encounter lifestyle. Through their combined and repeated use of lifestyle’s material and linguistic forms, they make possible its macrosocial dissemination to ever broader demographics and contexts, so that even the most debased products in our society—our cleaning supplies, toilet paper, and contraceptives—are now accompanied by hypertrophic tasting notes and thoughtful packaging.

Essays in Post-Industrialism: A Symposium of Prophecy concerning the Future of Society, eds. Ananda Coomaraswamy and Arthur Penty (London: T. N. Foulis, 1914).

Allan Antliff highlights the place individual that artisans held for Coomaraswamy and his cowriter—the guild socialist Arthur Penty—as they fleshed out the concept of Post-Industrialism: “Neither Penty nor Coomaraswamy sought a wholesale resuscitation of medieval institutions in Europe or India; their program idealized medieval societies in those countries as alternative ‘models’ for the social organization of the future in which spiritual values would shape every aspect of daily life … The most important feature of medieval society was the integration of spiritual idealism with the day-to-day activities of the population, primarily through art.” Allan Antliff, Anarchist Modernism: Art Politics and the First American Avant-Garde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001).

Ananda Coomaraswamy, “The Purposes of Art,” Modern Review 13 (June 1913): 606.

Ananda Coomaraswamy, The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon (London: T. N. Foulis, 1913), 34.

Ananda Coomaraswamy, Medieval Sinhalese Art (Broad Campden: Essex House Press, 1908), viii.

Ananda Coomaraswamy, The Dance of Siva (New York: Sunwise Turn, 1924), 138–39.

Bell notes his surprise in discovering the prior usage: “Ironically I have recently discovered that the phrase occurs in a book by Arthur J. Penty, a well-known Guild Socialist of the time … and called for a return to decentralized, small workshop artisan society, ennobling work, which he called ‘the post-industrial state’!” Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 37.

William Davies, “Neoliberalism: A Bibliographic Review,” Theory, Culture & Society 31, no. 7 (August 2014): 316.

Karl Marx, The Grundrisse, in The Marx-Engels Reader (New York: Norton, 1972), 382.

Julia Elyachar, “Phatic labor, infrastructure, and the question of empowerment in Cairo,” American Ethnologist 37 (2010): 452–64.

Nikolas Rose, The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

Andre Gunder Frank, The Development of Underdevelopment (New York: SAGE, 1966).

Joanna Cook, “Mindful in Westminster: The Politics of Meditation and the Limits of Neoliberal Critique,” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6, no. 1 (2016): 141–61.

Michael Storper and Susan Christopherson, “Flexible Specialization and Regional Industrial Agglomerations: The Case of the U.S. Motion Picture Industry,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77 (1987): 104–17.

Michael Silverstein, “Discourse and the No-thing-ness of Culture,“ Signs and Society 1, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 327–366, 349. For a broader discussion of “Oinoglossia,” see Michael Silverstein, “Indexical Order and the Dialectics of Sociolinguistic Life,” Language & Communication 23 (2003): 193–229.

Silverstein, No-Thingness of Culture, 329

In his history of early cinema, Georges Sadoul writes that Auguste Lumière’s need for film to run through a mechanism at a normal rate of speed made him think that a foot pedal from a sewing machine might function equally well in a film projector. Georges Sadoul, Histoire Général du Cinéma, vol.1 (Paris: Denoël, 1946), 184–96.

Jonathan Beller, “Dziga Vertov and the Film of Money,” Boundary 2 26, no. 9 (1999): 162. Italics in original.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version,” trans. Jephcott and Zohn, in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 4 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004): 101–33.

Dziga Vertov, Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984); John MacKay, “Vertov and the Line: Art, Socialization, Collaboration,” in Museum Without Walls: Film, Art, New Media, ed. Angela Dalle Vacche (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012).

John Thornton Caldwell, Production Culture: Industrial Reflexivity and Critical Practice in Film and Television (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008); Jerome Christensen, America’s Corporate Art: The Studio Authorship of Hollywood Motion Pictures (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012); J. D. Connor, The Studios after the Studios: Neoclassical Hollywood (1970–2010) (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015).

Caldwell, Production Culture, 232

Ibid., 3.

Although often regarded as merely a “receptor surface,” this question of “orientation” is key to the art historian Leo Steinberg’s discussion of the “flatbed picture plane”: “The characteristic ‘flatbed’ picture plane of the 1960s” insists on a “radically new orientation” towards it. Leo Steinberg, “Other Criteria,” in Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth Century Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975). 84–85.

The denouement of “Speculative Materialist” art, in the wake of the most recent Berlin Biennial, seems to have resulted from the movement’s inability to renovate a codified set of materials and talking points that had become vulnerable to ready-typification and parodic trolling from competing registers.