On the campaign trail in 2015, Trump stood triumphantly at the podium in Fort Dodge, Iowa, describing how he would deal with ISIS in Iraq:

I would bomb the shit out of ’em! I would just bomb those suckers. And that’s right, I’d blow up the pipes, I’d blow up the refineries, I’d blow up every single inch, there’d be nothing left. And you know what? You get Exxon to come in there and in two months—you ever see these guys, how good they are, the great oil companies? They’ll rebuild that sucker brand new, it’ll be beautiful. And I’d ring it, and I’d get the oil.1

The crowd erupts into applause, shocked and delighted by such an unapologetic and direct plan of action.

Trump speaks excitedly, as though he is the first person to think of bombing the shit out of Iraq. He speaks about the beauty of the burning oil fields remade in Exxon’s image. A year later, Trump’s words proved prescient. In the summer of 2016, oil fields across northern Iraq burned, with credit due not to Trump, but ISIS. Civilians in northern Iraq lived under a thick layer of toxic soot for eight months until the fires were finally put out in February 2017. Time will tell what damage, generational and in this lifetime, was caused to humans and the environment alike. Meanwhile, Trump also proposed a 10 percent increase—fifty-four billion dollars—in the US military budget, because we are going to win. What you can’t take by being a nice guy, you take by force. Beautiful women, oil fields, whatever.

The relationship between Iraq and the United States is intimate, toxic, and enduring. It is a relationship whose violence is generally dismissed as inevitable. It is made possible by many other partners, and kept exciting by still-unfolding entanglements. We grabbed Iraq by the pussy, and some people are very upset that it did not make America great again. Despite all the time and money we put in, we apparently did not get what we wanted. We did not win. Well she is crazy, that Iraq, full of toxic, bloodthirsty baggage. We tried to give her a chance at something good, but that’s what you get for being a nice guy, for trying to do the right thing. For all our shock at Trump and this administration’s language, it is not so far from the way violence has been dressed up and excused since the end of the Cold War. While the rhetoric from the first public announcement of the 1991 Gulf War to today has been more sophisticated than Trump’s, the president has, in effect, simply dissolved the veneer.

The shock at Trump’s words and actions, rather than an admission that this is a natural outcome of longstanding policy and general indifference, is a surprising gap. I’m not the first to speak about this; there are a number of authors who have connected exploitative foreign policy and the systems of control used to implement these policies to black and indigenous experiences in the US. We have to look at these experiences as bound up with one another. Humvees and war scenes at Ferguson and the Dakota Access Pipeline represent precisely this internal colonialism. Like Iraq, the Dakotas require a military presence to ensure policy acceptance and unencumbered resource extraction. However, mainstream discourse regarding these similarities generally stops with the idea that “it is a scene out of Iraq.” But what does that mean? What do we actually understand about Iraq’s impact and connection to American life, beyond its resemblance to the worst episodes shown on the news?

It seems that we have now entered an information war, an unprecedented era of “alternative facts.” But the first Gulf War was launched through a major information offensive. One day after Iraq invaded Kuwait, the Wexler Group, headed by Craig Fuller, was acquired by Hill & Knowlton, the most powerful public relations lobbying firm in Washington, DC. Fuller had been the chief of staff to George H. W. Bush when he was vice president under Ronald Reagan. Now, as president, Bush would soon announce the start of the Persian Gulf War. But before that happened, Hill & Knowlton was hired by a newly formed outfit, “Citizens for a Free Kuwait,” for more than ten million dollars. Nearly all the money came from the government of Kuwait, which hired the firm to galvanize American support for the war. The funds were well spent. With support from a focus group that counted Pepsi Cola as a client, Hill & Knowlton was able to find the perfect messenger to sway minds: a girl named Nayirah.2

Nayirah was a fifteen-year-old girl from Kuwait. Modest, with bangs and a long braid down her back, she gave highly emotional testimony to the US Congressional Human Rights Caucus on October 10, 1990 regarding atrocities she claimed to have witnessed inside the infant care unit at a Kuwaiti hospital. Her voice cracking, tears streaming down her face, she described babies being ripped out of their incubators by Iraqi soldiers, thrown to the ground, and left to die:

Mr. Chairman and members of the committee, my name is Nayirah, and I just came out of Kuwait. While I was there I saw the Iraqi soldiers come into the hospital with guns. They took the babies out of incubators. They took the incubators and left the children to die on the cold floor. It was horrifying.

Seared into the American imagination, this episode was told and retold by members of Congress in the months leading up to Operation Desert Storm. At one point, standing in front of a group of US soldiers, Bush referenced the babies “pulled from incubators, and scattered like firewood across the floor.”

The story was fabricated. The girl in question turned out to be the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador to the US. Tom Lanton, co-chair of the Congressional Caucus for Human Rights, knew her real identity, but said nothing. Citizens for a Free Kuwait also provided a fifty-thousand-dollar donation to the Caucus. The invasion of Kuwait did cause terrible violence and looting, though not the kind described in Nayirah’s testimony. It is also important to note that crimes by the Iraqi government were inflicted not only on the people of Kuwait, but also on the Iraqi populace as a whole in the decades prior to, during, and after Operation Desert Storm. Iraq’s regime led by Saddam Hussein had in fact long been supported by the US, despite being a dictatorship characterized by widespread, well-documented abuses and the violent suppression of independent, left-leaning movements.

Iraqi antiaircraft fire lights up the skies over Baghdad as US warplanes bomb the Iraqi capital in the early hours of January 18, 1991. The US campaign drove the Iraqis out of Kuwait in a little over a month. Photo: Dominique Mollard/AP.

It was against this backdrop that any lingering concerns over Desert Storm were soon overwhelmed by the first televised war—which did not disappoint. Journalists were in awe and given front-row seats in hotel rooms that provided a once-in-a-lifetime view of a Baghdad sky famously described as “lit up by fireworks.” The green lights of antiaircraft missiles sparkled with trails that zigzagged across a foreign landscape, as the post–Cold War military-industrial complex mounted a global display of its undiminished potency. Before the promise of big data was the promise of smart wars. The bombs over Baghdad made for a most impressive unveiling of the technologies soon to guide aspects of our lives as intimately as they guided missiles to their targets. The American public was introduced to real-time, living-room war games.3 This was what winning looked like.

That year—1991—the Super Bowl took place in Florida, at the height of military operations. Security was tight and the atmosphere was tense, though there were no credible threats. Even so, the New York Times noted that Tampa’s public safety administrator’s office “has asked the Federal Aviation Administration to prohibit flights close to the stadium except for regularly scheduled takeoffs and landings by commercial airlines,” adding that, “inevitably, the movie Black Sunday has been recalled here. In it, a Palestinian terrorist takes over a Goodyear blimp at the Super Bowl, planning to strafe the crowd.”4 Despite reporting no basis for concern—and despite the fact that at that very moment the US was deploying violence affecting Iraqi civilians—the New York Times inserted a scenario from a fictional Hollywood film to serve as a specter of Arab terrorism in the US.

This game was, as ESPN put it, the start of the branding relationship between the NFL and the US Army. Small American flags were put on every seat in the stadium for attendees to wave. Whitney Houston was brought in to sing the national anthem; subsequently released as a single, Houston’s rendition would make the song a Top 20 hit for the first time.

The performance by Houston was huge, replayed again and again.5 My junior high school in California played it at an assembly the following week, and teachers instructed us to send letters and notes to US troops. It was the time of yellow ribbons, when to criticize the war was to betray the troops, the innocent men and women—the only innocent men and women, it was to be understood—of this conflict. This was also the first year that the Super Bowl enlisted contemporary pop stars for the halftime show. The year before, the halftime show had featured an Elvis impersonator. Though most outlets broadcast a news update, the 1991 Super Bowl was the first iteration of halftime as popular spectacle.

At the halftime show, hundreds of little girls dressed as cheerleaders swarmed the stage, dancing and singing about rich men, football stars, and beautiful girls.6 Lyrics sung by the mini-cheerleaders, looking no older than eight or nine, repeated, “You’ve gotta be a football hero to get along with the beautiful girls. If you are rich or handsome it’ll get you anything!” A few minutes later, their counterparts, hundreds of young boys dressed as football players, ran onto the stage. One, with a blonde bowl of hair, took the microphone and solemnly sang the Bette Midler hit “Wind Beneath My Wings,” as images of troops in the Persian Gulf played across the screen. Children of the troops were paraded onto the field, and a live message from George and Barbara Bush was broadcast from their living room, blessing America, the Super Bowl, and our troops.

Then a replica of the Disneyland spectacular It’s a Small World After All took center field, as Mickey Mouse, dressed to look like Uncle Sam, burst out with a parade of children in various international costumes. The children and Disney characters all linked hands, singing “We Are the World” and “It’s a Small World After All” as the camera panned across a sea of multinational faces and flags, mirroring the coalition of countries in the Gulf. A small world united by war, and our children. This is why we fight. This is why we win.

And win we did. Norman Schwarzkopf—commander-in-chief of the coalition forces—was gruff and respected, a tough-love coach who showed us the way to victory. There were whiteboards with the various teams laid out (remember, this was a thirty-four-member coalition, with more than half the war costs covered by Kuwait and Saudi Arabia), patiently describing how we did it. He also had a great sense of humor. At one of his press conferences, he had a small television set brought out to replay various bombings and attacks from the air. He concluded by introducing us to “The Luckiest Guy in Iraq.” In the video, we see the movement of a vehicle across a bridge. Seconds after the vehicle passes, the bridge explodes—to laughter from the press.7 This is meant as a lighthearted moment. The man is alive, and all he has to show for it is witnessing a bridge bombed just behind him and a war waging, literally, all around him.

Schwarzkopf later explained why some Iraqis were not so lucky. At the end of the war, George Bush made several statements, broadcast inside of Iraq by Voice of America radio, encouraging Iraqis to “rise up.” Logically enough, Iraqis took this to mean that if they revolted against the Hussein regime, the US would support them. And rise up they did. In the north and south of Iraq, major rebellions, often celebratory, broke out. The optimism was short lived, as the US had agreed, in the ceasefire agreement, to allow Iraq to resume flying military planes over the country. Soon, the north and south were attacked from the sky, driving hundreds of thousands of Iraqis into the mountains of the north and the deserts of the south.

Schwarzkopf, the celebrated strategic military mastermind of the war, led us to believe that he had no idea that allowing the regime to fly armed aircraft over the country would result in a swift crushing of the rebellions. He claimed that he was left alone with no guidance as to how to work out the ceasefire agreement. In countless interviews and commentary, US military and political figures spoke of the complicated makeup of Iraq and the possibility of a “quagmire” if further involvement in the country was pursued.

We see here the precursor to the militarizing of sect and ethnicity. Kurds and Shia become “factions” rather than citizens with commitments and concerns. “I don’t think that we should ever say that because of what’s happening to the Kurds now means that our mission failed,” said General Schwarzkopf in the aftermath of the ceasefire agreement. He continued:

It’s exactly the same thing that happened to the Kurds a few years ago at the end of the Iran-Iraq War. It’s exactly the same thing that’s happened to the Kurds for many years. Yes, we are disappointed that that has happened. But it does not affect the accomplishment of our mission one way or another.8

All of this resulted in one of the largest and most deadly mass migrations in history, a precursor of what was to come. At its height, nearly a thousand people died each day, with thirty-five to sixty thousand dying in total. More than a million fled, with Iran taking in many of the refugees. Nearly twenty-five thousand people remained in Camp Rafha, a desolate camp in the Saudi Arabian desert, for more than a decade.

As this tragedy unfolded, a contract was signed between the US government and the Rendon Group in 1991. The Rendon Group was headed by John Rendon, a former Democratic National Committee director turned self-described “information warrior.” He had also been hired by Citizens for a Free Kuwait to manage public perception. During a speech he delivered at the National Security Agency, he told a story about this work: “Remember those little flags the Kuwaitis were waving around as the tanks rolled in? How do you think they got those? Let alone flags of the coalition nations? That was me.”

This Rendon Group contract, however, was for a much bigger job, with a much higher, multimillion-dollar price tag: to push for the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. During the next decade, Iraqi human rights abuses, so heartbreakingly real, were consistently manipulated in the service of paid CIA operatives and exiled collaborators. This information war, along with real legislation to make the overthrow official US policy (notably, the Iraq Liberation Act, signed by Bill Clinton in 1998), would eventually lead to the fabricated “weapons of mass destruction” claim, infamously printed on the front page of the New York Times above an article by Rendon Group ally Judith Miller. These false claims were chillingly referenced by key leaders like Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice: “We don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.”

But as the second Gulf War loomed in early 2003, it was hugely unpopular, provoking massive protests worldwide. Something more was needed. “Shock and Awe” was a campaign that used military and visual force to knock Iraqis, and the memory of the record-breaking protests, off their feet. No longer in green-and-black night vision, this war was rolled out in full color. Huge bombs rocked the buildings across Baghdad’s riverfront, with screens flashing white from the intensity of the explosions. As the strikes hit, news tickers went from reporting the size of the antiwar rallies to providing updates on military advancements.

The antiwar movement had lost. The US Department of Defense ensured that journalists from major news outlets were embedded with US forces, breathlessly reporting from tanks and Humvees. Things were going well—until, of course, they weren’t. Nighttime raids went horribly awry, images from Abu Ghraib were leaked, militias and gangs waged an internal war that killed three thousand people a day at its height in 2006. Journalists were being killed at an unprecedented rate, along with everyone else. And as many books written about the conflict would later attest, it was also one of the most corrupt wars in history, with rampant cronyism and graft. It was all so chilling, confusing, morbid, and impossible to keep up with; you didn’t want to look, and so, many did not.

In 1992, 60 Minutes did an interview with a vice president of Hill & Knowlton, Lauri Fitz-Pegado, who had met with Nayirah and worked on her Kuwait testimony.9 The interviewer was seeking some kind of accountability for Nayirah’s misleading story. After reading a statement from Hill & Knowlton denying any culpability for working deceptively towards the war effort, Fitz-Pegado expressed no regret: “I’m sure there’ll always be two sides to a story. I believe Nayirah, I have no reason not to believe her. The veracity of her story was indelibly marked on my mind, when I saw her and when I talked to her.”

Again, it was clear back in 1992 that privatizing the war effort would not only be effective but also that, acting through a corporation like Hill & Knowlton, the government itself would never be held accountable. This has, over and over again, proven to be the case. Even the initial shock of Abu Ghraib is a distant memory. A handful of low-level soldiers were prosecuted, but no one at the top of the government chain of command was charged. CACI International, the prison firm that ran a section of the prison where abusive interrogation took place, has never experienced any blowback. On the contrary, it retained its contract and its profits. In addition, eight months after the Abu Ghraib abuses—rape, torture, and death, which the press referred to as merely a “scandal”—General Keith Kellogg, who was previously director of operations for the Coalition Provisional Authority, in charge of assuring compliance with the billions of dollars in corrupt contracts, took a position as executive vice president at CACI International. Today, he serves as chief of staff of the United States National Security Council in the Trump Administration.

In a special investigation conducted by The Nation in 2007, fifty combat veterans were interviewed. The report noted that

two dozen soldiers interviewed said that callousness toward Iraqi civilians was particularly evident in the operation of supply convoys—operations in which they participated. These convoys are the arteries that sustain the occupation, ferrying items such as water, mail, maintenance parts, sewage, food and fuel across Iraq. And these strings of tractor-trailers, operated by KBR and other private contractors, required daily protection by the US military.

As a former sergeant put it,

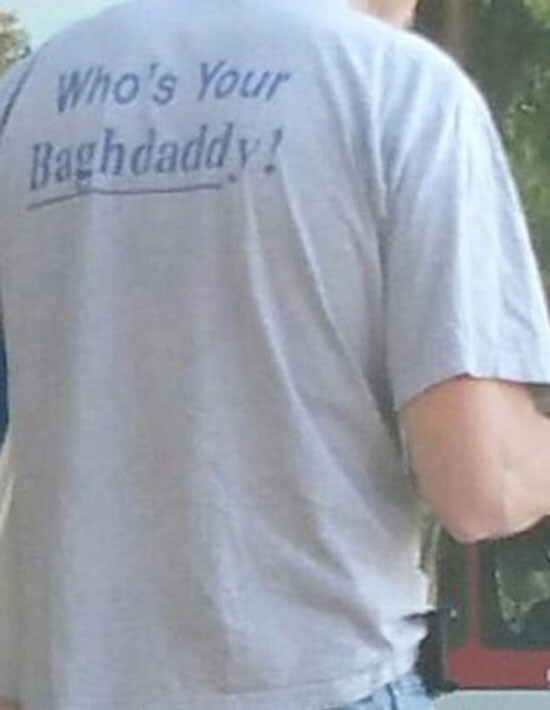

We’re using these vulnerable, vulnerable convoys, which probably piss off more Iraqis than it actually helps in our relationship with them, just so that we can have comfort and air-conditioning and sodas—great—and PlayStations and camping chairs and greeting cards and stupid T-shirts that say, Who’s Your Baghdaddy?10

The author’s snapshot of the infamous US army occupation slogan.

The above image of the shirt does not come from the Nation article. A few months ago, I was sitting outside a coffee shop on a beautiful California morning with my mother and one of her best friends, also Iraqi and in her early sixties. I bring out their coffee and see this guy, tall, late-forties maybe. He’s standing, chatting with a friend a few feet away, wearing the shirt. I freeze for a moment and look at my mom and her friend, and they look at me quizzically, what does the shirt mean? They both speak perfect, heavily accented English, and are both scientists, not dense. At first I was angry at him for the shirt, then I felt something I’m not sure I can describe. It was this terrible thing. On the one hand, it’s funny—haha, who’s your daddy? On the other, it means I own you baby and you like it. You get me off daddy and I like it. And this is said by an occupier, an invader. We grabbed your pussy. Tell me you like it. How do you explain that to two moms? Who’s your daddy? Who’s your Baghdaddy? This beautiful city, with all of its beautiful people and its histories, their histories, already ravaged and now reduced to this T-shirt. How could I tell them that? My mother and her friend, so proper and good natured, always wanting to remain optimistic, sitting in the sun, troubled by their confusion. I couldn’t. I told them it was just something silly, a stupid saying. I changed the subject.

We might—and I often want to—think that this is history, it’s old stuff. But this is the dissonance: we still haven’t come to terms with this shirt, this narrative, this violence. It’s still okay, sometimes even funny, to parade about in public wearing this shirt, in our coffee shops, our newspapers, our galleries. (Indeed, many well-meaning people thought the shirt was funny when I first showed it to them.)

Why haven’t we reckoned with this? Instead, we have articles like “What We’re Fighting For,” published on February 10, 2017 in the opinion section of the New York Times.11

The piece recounts the honorable way the author and his fellow soldiers fought in Iraq. Even his references to a colleague at Abu Ghraib mention only the lightest use of harsh tactics: slapping young men for information. The author does not approve of these tactics, but paints a holistic picture of the effort in Iraq as one solely of honor and courage. I do not doubt that this was the case for some, but it has proven to be far from the truth for all. At the end of the article, the author references an Iraqi soldier who was killed, and notes that had he been saved,

the enemy soldier would have ended up with a unit like mine, surrounded by doctors and nurses and Navy corpsmen who would have cared for him in accordance with the rules of law. They would have treated him well, because they’re American soldiers, because they swore an oath, because they have principles, because they have honor. And because without that, there’s nothing worth fighting for.

It is a bizarre conclusion to an article accompanied by an image of bound, blindfolded Iraq men kneeling at the feet of American soldiers in a barren desert.The article is presented as though there is no shameful history of Iraqis being rounded up, hooded, and detained by the US military, often only to be let go with no charges after they and their families endured terrifying, humiliating ordeals at best, fatal or torturous outcomes at worst. It is presented as though thousands of Iraqi men have not been held and routinely killed, by various actors since the invasion, in mass graves littered throughout the country. Instead, this image is turned into a national call. Bowed and handcuffed Iraqi men, embodying, illustrating What We’re Fighting For.

A day earlier, artist Francis Alÿs had written in Artforum about his experience being embedded with Peshmerga soldiers in Mosul, Iraq during the battle against ISIS. He posed a number of questions:

What could the ISIS fighters possibly make of the rain? Strangely it brought us closer, we shared that moment. Did I film the rain? Is art just a means of survival through the catastrophe of war? Do we live because we narrate? … This particular war? Because it is local, tribal, and religious conflicts that have had extraordinary repercussions on more than half the planet. It’s medieval barbarism perpetrated and spread with the most modern of technologies. An existential war.12

This use of “clash of civilizations” rhetoric, of the gap between the barbaric and the civilized, and the always violent echoing of sectarian language, exemplifies how the arts mimic the tropes of information warfare. It also mimics the use of authority: a well-known French male artist can give us a glimpse into this odd, terrible world. Medieval barbarism? The City of Sammara, one of the biggest archeological sites in the world, celebrated for its spectacular Abbasid-era minarets, became a notorious torture site when US operatives used the public library to train Iraqi police and Special Forces, transforming it into a brutal interrogation unit that eventually engulfed the city in violence. Hardly a medieval phenomenon.

During the course of the work I undertook for several years with art students in Baghdad, I received incredible support from various members of the arts community. But I would be remiss if I did not also discuss a very disturbing acceptance of sophisticated, supposedly good intentions over the work of building new processes to bring people in. When I would tell people what I do, more often than not they’d express curiosity: What’s happening there? What medium are people using? Any interesting events? What’s the scene like? I would answer these questions, themselves violent in their ready willingness to ignore every facet of what was and is taking place: the wholesale degradation of infrastructure, and with it, the conditions under which young artists work.

How much do most know of the arts in the Middle East beyond the Gulf States, which have poured billions into PR-friendly arts while maintaining their role as the US’s main economic partner and builder of military bases (where construction workers are paid a miserably low wage)? So many of us still want to believe the Muslim ban is just a Muslim ban, solely about Islamophobia and not about unending warfare in strategic areas. Do we even look at why these states are exempt? It is not just because Trump has hotels there. These hotels pale in comparison to the billion-dollar US military installations and accelerating military activities.

The names of the seven countries included in the ban first surfaced years earlier in comments made by Wesley Clark, a highly decorated former US military general, former NATO commander, and one-time US presidential candidate. He publicly stated that just before the 2003 invasion of Iraq, he was told of a high-level memo outlining a strategy to take out seven countries in five years. Those countries? Iraq, Iran, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Lebanon. He said this long before Trump was even on the radar. By 2017, Lebanon had long been replaced by Yemen, the Arab world’s poorest country, currently in the midst of a historically devastating war waged by the region’s richest country, Saudi Arabia (supported in the conflict by the US). Why are we still reducing these policies to religious identities and Islamophobia? It is a distraction tactic, and many on the left happily eat it up rather than looking at the clear, ongoing politics involved. Islamophobia is real, yes, but a far more effective counter would be to disengage it from American political ambitions rather than amplify its use.

I bring up the situation of artists in Baghdad not because I think only Iraqi art students deserve a shot, but because it shows how willing we are to be contained by clean places, language, and events, and how much we are missing out in doing so. The things that these young people know about are things we couldn’t even begin to understand in our lifetime. They have lived through a multinational takeover, militarized violence by the world’s strongest armies, and dizzying messaging campaigns, all within a bustling, major metropolitan city with unrivaled history. It is our loss not to know, not to understand, not to learn, as much as it is their position to feel unheard and unseen in the most infamous, embattled city on earth—a position some of us may find ourselves in soon enough.

See →.

As reported by 60 Minutes in 1992.

See →.

Gerald Ezkenazi, “SUPER BOWL XXV; Further Security For Game Unveiled,” New York Times, January 23, 1991 →.

See →.

See →.

See →.

See →.

See →.

Chris Hedges and Laila Al-Arian, “The Other War: Iraq Vets Bear Witness,” The Nation, July 10, 2007 →.

Phil Klay, “What We’re Fighting For,” New York Times, February 10, 2017 →.

Francis Alÿs, untitled article, Artforum, February 9, 2017 →.