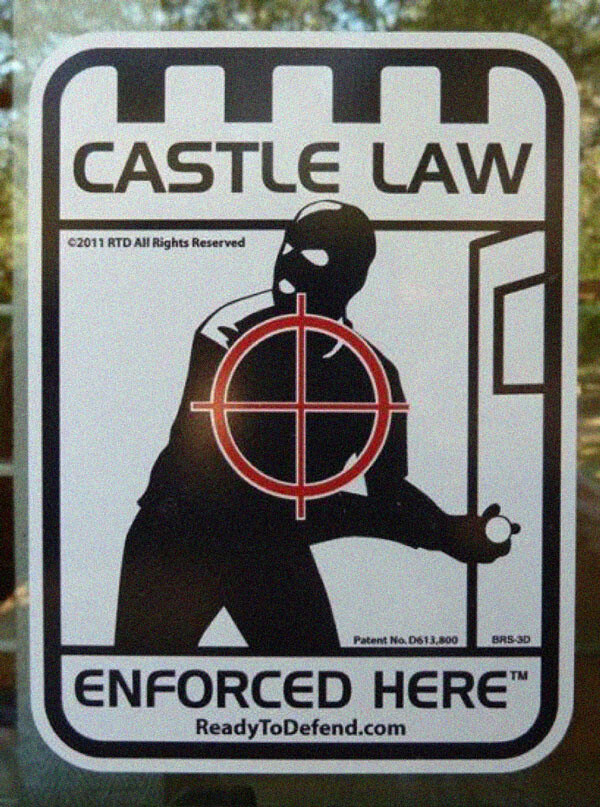

I first noticed the ubiquitous signs when I moved to Los Angeles in the 1990s. They festooned the forecourts of houses, front and back gates, porches, fences, window ledges, and driveways. They peeped out of shrubbery, and dotted emerald lawns. Stranded between a marketing tool for security companies, a feature of militarized gardening, and a status symbol of affluence and domestic self-regard, the signs sported the ominous phrase “Armed Response.” I pondered the range of associations in that charged phrase. The army, la société de contrôle, gun violence, home invasion. The signs telegraphed a host of warning interpellations: Achtung! Listen up! Man is his castle! Stand Your Ground! This building is armed!1 They telegraphed a logic of preemption: “If you’re staking out this property or putting the security of its occupants in jeopardy, think again! Police and security details standing by! Cameras and motion detectors in place to record your every move, your kinetic bioprint goes straight to the criminal database! Suspicious noises will trigger the alarm!”

“Armed Response” conjures surveillant technologies of domestic fortressing, protections against incursions on “my privacy,” citizens’ militias, the prophylatic infrastructures of risk reduction, apopotraic shielding, and something more—let’s call it the technical apparatus of judicial hearing defined by the right to “make the call” (even a lethal one) on what is being heard or what it means “to respond to.” For what is translation if not first and foremost an adjudication of response to verbal and sonic cues? An act of translational justice? Armed response affords a literal translation of the French expression “traduire en justice” (normally rendered in English as “to prosecute,” “to levy criminal charges”). It conveys the sense of “to translate in or into justice,” as if “justice” were the name of a discrete language. It communicates laying down the law, lying down before the law, or being “down by law” (prison slang for having someone’s back).

The concept of armed response, cast as exemplary of “translation in-justice,” refers to operations of militarized policing, state patrols, privatized security sectors, local militias, and “Neighborhood Watch” groups endowed with far-reaching discretionary powers. Operating at the edges of the law, often in extrajudicial zones of the justice system (like spaces of extreme rendition and covert interrogation or citizens’ militias that play host to vigilantism), the phrase “Armed Response” effectuates an unexceptional state of exception, whereby domestic privacy is routinely breached in the name of security, forcible entry authorized, and use of force justified in the name of prevention. Whether it is in the name of derailing drug deals or routing illegal immigrants, there is a kind of pretrial, or predetermination of guilt, associated with “making the call.” It is this call (anchored materially in the history of the telegraph: ADT, the largest home security company in the US and Canada, stands for “American District Telegraph”) that will justify the transgression of eminent domain as well as tactics of no-knock arrest and property seizure. Armed response, in such contexts, mobilizes translation as a control-society mechanism of what Peter Szendy calls “panacousticism,” or “overhearing” (in French, Szendy’s neologism surécoute also translates as “overlistening”).2 To translate in these terms is to subjectivate by ear, to act on hearsay or tip-offs from informants, to have recourse to a metalanguage of security equipped with euphemistic monikers like “Critical Armed Response,” “Dynamic entry,” “Forcible entry raid,” “Task Force Raptor.” Armed response encompasses acts of selective hearing, as well as underlistening—to wit, the case of Philando Castile, whose fatal shooting aftermath was livestreamed on Facebook by his girlfriend Diamond Reynolds. Castile was shot by Officer Jeronimo Yanez as Castile reached toward his glove compartment for his ID and gun permit. The officer claimed to hear only the word “gun,” enough to justify the use of deadly force. (Yanez was recently acquitted of the killing.)

The play between “response,” understood as an open ear to the other or as a form of aural excitation (exciter in Latin, as Jean-Luc Nancy reminds us, “means to call on someone to come out, to call outside”), and “Armed Response,” understood as a techne of weaponized hearing, will shape my concerns.3 But first, to better grasp what an “Armed Response” looks like, Hollywood-style, here’s the opening scene of the film Straight Outta Compton, in which an escalating dispute between LA drug dealers is eclipsed by a full-on police raid.

“Real life” accounts of incidents like this, while less sensational, are even more frightening in capturing the randomness of collateral damage. Kevin Sack’s New York Times article “Door-Busting Raids Leave a Trail of Blood” captures this effect, opening with a chilling narrative vignette:

At 2:15 a.m. on a moonless night in May 2014, 10 officers rolled up a driveway in an armored Humvee, three of them poised to leap off the running boards. They carried Colt submachine guns, light-mounted AR-15 rifles and Glock .40-caliber sidearms. Many wore green body armor and Kevlar helmets. They had a door-breaching shotgun, a battering ram, sledgehammers, Halligan bars for smashing windows, a ballistic shield and a potent flash-bang grenade.

The target was a single-story ranch-style house about 50 yards off Lakeview Heights Circle. Not even four hours earlier, three informants had bought $50 worth of methamphetamine in the front yard. That was enough to persuade the county’s chief magistrate to approve a no-knock search warrant authorizing the SWAT operators to storm the house without warning.

The point man on the entry team found the side door locked, and nodded to Deputy Jason Stribling, who took two swings with the metal battering ram. As the door splintered near the deadbolt, he yelled, “Sheriff’s department, search warrant!” Another deputy, Charles Long, had already pulled the pin on the flash-bang. He placed his left hand on Deputy Stribling’s back for stability, peered quickly into the dark and tossed the armed explosive about three feet inside the door.

It landed in a portable playpen.4

The more one watches clips such as the ones the New York Times published, the more it becomes almost impossible to distinguish who is responding to whom and how. The roving, jerky movements of the body cameras provide fleeting glimpses of SWAT-team pileups, and stunned residents pinned or frozen in their daily rituals. The soundtrack is even more telling. We discover a peculiar cipher, mixing intelligible words, inaudible speech, guttural sounds, and noise, punctuated by the pounding of doors, the crash of battering rams, shouts, shots, explosions of matériel, exclamations of surprise, stress, and fear. In one clip, “Abre la puerta!” or “Open the door!” becomes the caption in a grim playbook. Here, bilingual enunciations position the speakers on different sides of the law. As a police command, the phrase in Spanish performs a judgment call of guilt-by-association. A Hispanophone suspect is presumed to be an employee of a drug cartel, an illegal immigrant, a “bad hombre.” Here, the concept of “traduire en justice” applies to the practice of language profiling (what the artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan identifies as treating “the voice as if it were a birth certificate or passport,” whereby the form of speech itself is under investigation).

Abu Hamdan’s work considers translation under coercive circumstances: accent tests administered on asylum seekers, language profiling at border checkpoints, the practice of taqiyya, i.e., the right to remain silent or withhold language from translation in the face of religious and political persecution. In his video work Rubber Coated Steel (2016), the politics of listening plunges us into the material forensics of judicial hearing in both senses of “hearing,” as trial and as a way of deciphering acoustic signs. The subject matter is drawn from an actual court case held in May 2014 concerning two unarmed teenagers, Nadeem Nawara and Mohamed Abu Daher, who were shot and killed by Israeli soldiers in the occupied West Bank. Abu Hamdan’s project takes the form of an imagined courtroom transcript in which an audio expert is brought in as a witness for the prosecution to provide forensic analysis of the lethal shot. The defense claims that because the soldier’s rifle was fitted with a rubber-bullet adapter, it was impossible for him to fire live ammunition. The prosecution alleges that the army used a rubber-bullet adapter as a decoy or alibi. Using a spectrogram that enables visualization of a bullet’s “sonic signature,” measured by the ratio of speed to sound (a real bullet breaks the sound barrier), the audio witness identifies the fatal shot as the one showing higher frequency on the spectrum. For the defense, this allegation about the rubber-bullet adapter is unproven, based on hearsay. But the prosecution argues that Palestinian children have developed such advanced powers of auditory discrimination that they can identify the nature of the ammunition being used. Meanwhile, the judge entreats the audio expert to explain what he is hearing, because he professedly has a “tin ear.”

Even as Abu Hamdan’s video attends to what armed response sounds like (by graphing what it looks like), it demonstrates how difficult it is to render justice by ear.

Determinations of acoustical “rightness” depend on the ear of the listener, as Mladen Dolar reveals with a joke about “failed interpellation.” Taking off from a line of Plutarch’s Moralia: Sayings of Spartans—“A man plucked a nightingale and finding but little to eat, said ‘You are just a voice and nothing more’”—Dolar describes the plight of a commander in the Italian trenches unable to elicit a response to his order to attack.

He cries out in a loud and clear voice to make himself heard in the midst of the tumult, but nothing happens, nobody moves. So the commander gets angry and shouts louder: “Soldiers, attack!” Still nobody moves. And since in jokes things have to happen three times for something to stir, he yells even louder: “Soldiers, attack!” At which point there is a response, a tiny voice rising from the trenches, saying appreciatively, “Che bella voce! [What a beautiful voice!]”5

The humor of the joke turns on an illocutionary performative of baffled messaging: we assume the teller has already translated the commanding command from the Italian. The punch line reveals this assumption, and the joke is on us. More significantly, it underscores the aesthetic factor in determinations of what is heard or misheard.

To hear “rightly” is to register acoustical rightness or trueness not only by means of forensic acoustics, or by moral criteria of right and wrong, but according to measures of rhythmic beauty (euruthmoi) and mellifluous accompaniment. “To accompany” (akoloutheî means to follow or to flow from) lies at the heart of what Plato, in the Republic, identified with the poetic. For Plato, just as matter must follow soul, so musical harmony and rhythm must follow poesis. Good rhythm in this sense accompanies, agrees with, or “goes along with” fine speaking. For Plato, making a “right” republic necessitates allowing the superior register to lead, and ensuring that its accompaniment be a good match.6 We could say that Plato gives us the “good match” theory of just translation.

But what exactly is “just translation?” A matter of timing, of knowing when and when not to translate? A question of translation’s bounds or limits as a praxis grounded in the work of textual rewording and inter- or intralingual transmission? A protocol for medial transposition on certain conditions? A demonstration of fidelity to the absolute of one meaning or sense under oath? A matter of negotiating a response to Aristotle’s “things in the voice” (what Daniel Heller-Roazen playfully calls “a thinking of grammar that leaks out of the cave”) that defies the logic of nominalism, statement, and proof, and mobilizes all matter of nonapophantic utterances, from “ridiculous sentences” (“Spirit is Spirit”), perplexing speech phenomena, indefinite names, and inarticulate noises, to the cries of beasts?7 In No One’s Ways: An Essay on Infinite Naming, Heller-Roazen tracks such forms of indeterminate expression as they interfere with the metapragmatics of speech, derailing the path of reason towards truth. This obstruction of reason brings to mind Derrida’s excursus in The Animal That Therefore I Am on Lewis Carroll’s Alice—her exasperation over the fact that kitty’s constant purr makes it “impossible to guess whether it meant ‘yes’ or ‘no.’” “Isn’t Alice’s credulity rather incredible?” queries Derrida. “She seems, at this moment at least, to believe that one can in fact discern and decide between a human yes and no.”8 Elsewhere Derrida writes, describing encounters with indecipherability, “It is always difficult to read what does not let itself be translated”—as when the insect, cut in half, becomes a figure for sentences that have a “sectional” life in their capacity to “move forward and back,” making meaning “swarm.” Where indefiniteness meets infinitude, Derrida identifies the abyss of language’s “infinite reserve” (sa réserve infinie) and “innumerable multiplicity” (la multiplicité innombrable).9

Ultimately, it would seem to be impossible to delimit what is “just translation” within the wide parameters of “being” in and across languages, or across sound and sense spectrums and orders of animacy. For this reason, rather than take the question of “what is just translation?” to mean what is “only” translation (as opposed to some other way of relating to language or non-speech), we would do better to shift the emphasis to the “just” in justice, orienting translation theory toward the politics of hearing rightness or rightly. Justesse, as a body of aesthetic principles, would, to this end, train attention on the politics of ethical relation as well as on the extent to which translational norms of correspondence, equivalence, harmony, and hierarchy are imbued with the force of law, embedded historically in the criminal justice system, and normatively inscribed as regulatory mechanisms of legal reason and reason of state.

Derrida’s essay “Justices” (published in Critical Inquiry in Peggy Kamuf’s translation in 2005 and in French in a 2014 volume of essays titled Appels) gives us a way of theorizing “just translation.” The text pays tribute to a friend and colleague, the literary critic J. Hillis Miller, and involves a reading of Miller’s 1963 book The Disappearance of God: Five Nineteenth-Century Writers (1963), in which the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins was foregrounded. Hopkins’s notion of “justified” self-being calls to mind analogies with the justified margin in a page of text where the words all fit; where the aleatory semiosis of difference and deferral is formally rectified; where, as Wai Chee Dimock puts it, justice speaks “a language of structural guarantee” that “demands from the world a grammatical uniformity … an adequating rationality [that] images forth the world as a commensurate order, so that problem and solution are not only reflexively generated but also instrumentally corresponding.”10 But where Dimock is concerned with the worldly scoring of correspondences between grammar and justice, Derrida sources in the poet Hopkins an aesthetics of rightness that is all process and praxis; it is contained in the untranslatable neologism “to justice” coined by Hopkins in his poem “As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” which reads:

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves—goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying What I do is me: for that I came.I say more: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: that keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is—

Christ—for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

Referencing the first line of the second stanza, Derrida writes:

Hopkins does not name only the just; he also uses the word justice, but otherwise than as a noun. He has the magnificent audacity of an unusual verbal form: to justice, justicing, the act of doing justice, of justifying justice, of putting justice to work, operating a justice that, by rendering justice outside, in the world and for others, remains itself, remains the justice it is, carrying itself out in the world without going out of itself. To justice is intransitive even if justice, by justicing, does something, although it does nothing that is an object. Justice shines forth, it radiates and so does the just.11

“Justicing,” the text implies, is an ethics of writing and teaching, but it is also, we could say, an intuition of right translating that at least in theory eventuates in confounding the misattribution of “poetic justice.” When we say “poetic justice” in English, it suggests “just desserts,” appropriate punishment, or still more colloquially, the folk wisdom that “what goes around comes around” in the grand distributive scheme of slights and injuries meted out and returned in kind. But for Derrida, when Hopkins (and Miller) “justice” something, there is a more singular meaning to be harvested. First, the right meter, close to natural speech, and which Hopkins called “sprung rhythm”; and second, something along the lines of Émile Benveniste’s “middle voice” (la voix moyenne), an important point de repère in Derrida’s seminal early essay on “la différance.” Benveniste’s concept of middle voice has been taken as a way of describing intransitive modes of intersubjective address, whereby the exclusivity of the I-thou circuit is interrupted, and the subject, as Irving Goh would have it, is pre-positionally (as well as prepositionally) situated in the netherworld of à (in the sense of à venir—to come, to arrive, “to be” in aporia, to differ); in short, a state of being without fixed abode, temporal emplacement, or entelechy.12 The middle voice provides access to what Jean-Luc Nancy designates “arch-sonority”—an arké-sonority of existence that points to the originary soundings of subjective resonance and the start-time of auricular dehiscence.13 To become attuned to the middle voice is to master the art of oto-ontological responsiveness, a capability of “hearing” ontology, or hearing being (das Seiende) as it exists.14

“Justicing,” from this perspective, implies an address to being achieved through a sublatory dispensation, one that destabilizes and deconstructs the economy of debt and legal calculation. This argument is laid out in Derrida’s famous essay “Qu’est-ce qu’une traduction ‘relevante?’” (“What is a ‘Relevent’ Translation?”), where he begins by associating “relevant” with aesthetic rightness. “Relevant” is

whatever feels right, whatever seems pertinent, apropos, welcome, appropriate, opportune, justified, well-suited or adjusted, coming right at the moment when you expect it—or corresponding as is necessary to the object to which the so-called relevant action relates: the relevant discourse, the relevant proposition, the relevant decision, the relevant translation. A relevant translation would therefore be, quite simply, a “good” translation, a translation that does what one expects of it, in short, a version that performs its mission, honors its debt and does its job or its duty while inscribing in the receiving language the most relevant equivalent for an original, the language that is the most right, appropriate, pertinent, adequate, opportune, pointed, univocal, idiomatic, and so on.15

Here we find ourselves back in the familiar territory of justesse defined as that which is exact, true, and proper, as in disegno: correct lines, true measures, right angles, well-drawn or pleasing resolutions in design, or the satisfactory construction of a load-bearing grammatological architecture. There are echoes of Flaubert’s quest for le mot juste and calculation of the correct ratio of punctual rhythm to expressed thought. In a letter to Louise Colet, Flaubert projects this ideal style, which would be “rhythmic as verse, precise as the language of the sciences, undulant, deep-voiced as a cello, tipped with flame: a style that would pierce your idea like a dagger, and on which your thought would sail easily over a smooth surface like a skiff before a good tail wind.”16 Derrida would also seem to allude to the time of decision, the “right” moment of the revolution or messianic end, or of the precise, opportune time of the “equivalent’s” arrival at the door of the original. In play, too, is the doublet lex/jus, which connects law to oath, public office, and Roman canon law, which decreed the foundations of towns, the so-called “natural” union of man and woman, and the legal status of animals. Rightness (from Kant to Mill) refers to a dictate or imperative of reason that prescribes certain actions—a sense of moral rectitude or duty fulfilled through obedience to the categorical imperative, an aspiration to freedom defined as individual autonomy. With this meaning, there is the allusion to doctrines of natural and legal right: the Lockean right to property in the person, the right to human rights, the right to speak your language (recognized in the 2007 Declaration of Indigenous Rights). And finally, there is the persistent line of intellectual pursuit, apparent in a lifetime of texts and seminars, of the Derridean right to literature, right to philosophy, right to translation, right to have rights.

Bringing Hegel to bear on Shakespeare, Derrida will proceed to deconstruct the formal and historical coordinates of “relevance,” drawing on the supercessionary power of “la relève.” In his reading of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, the play’s metaphors of “economy, calculation, capital, and interest” come to a boil in the “unpayable debt to Shylock.” This debt carries over to the French translators of Shakespeare, who are effectively inveigled into a “transferential and countertransferential contract” that dooms them to “treason and perjury,” to offenses punishable by death. “Insolvent indebtedness,” the ground zero of the translator’s “task, his duty,” introduces a crisis of credibility that threatens the entire system of ethics and belief in Abrahamic traditions. Left with only unreliable regulators of transmission, we face the prospect of “responding to” in the vacuum of relativism.

Disestablishing the laws of general equivalence, consigning subjects to the fate of ceaselessly “weighing in” amid a sea of relative and relational comparisons, Derrida loosens the strictures of the force of law on translated subjects. But in the same movement he enters us into a lawless territory of untranslatability fraught with microaggressions and fears of armed response. Here we would effect a small but crucial axial shift from Derrida’s “différance” to Jean-François Lyotard’s “différend,” remembering that the differend refers to particular states of adjudicative stalemate in Lyotard’s ascription. First and foremost a “phrase in dispute,” the differend describes an unlitigable condition in language, whereby “you have a conflict, between (at least) two parties, that cannot be equitably resolved for lack of a rule of judgment applicable to both arguments.”17 A zero-sum logic prevails, because “applying a single rule of judgment to both in order to settle their differend as though it were merely a litigation would wrong (at least) one of them (and both of them if neither side admits this rule)” (D, xi). One example Lyotard uses is known as the Paradox of the Court, from the Latin author Aulus Gellius’s Attic Nights, a logic problem based on Protagoras’s standoff with Euathlus, the latter of whom is refusing to pay Protagoras’s fees as a debate coach because he has not “won a victory yet’” (D, 6). The two opponents reach a contract that, rather than resolving their conflict, provides a kind of you-lose-you-win work-around akin to the liar’s paradox (“Everything I say is false”), or a variant of it, the paradox of Buridan’s bridge (where Plato’s aggressive sophism “Socrates, if you first say something true, I will let you pass, but if you say something false, I will throw you in the water” is met by Socrates’s wily rejoinder: “You will throw me in the water”). In the same vein, Protagoras makes the point that if the dispute over payment goes against Euathlus, the money will be due to Protagoras in accordance with the verdict, but if the decision goes in Euathlus’s favor, the money will still be due to Protagoras according to the terms of the contract, since Euathlus will have won a case. For Lyotard, Protagoras relies on the logic of antistrephon, a dilemmatic argument in a lawsuit that allows each side to use it against the other with the hope of a successful outcome, or more colloquially, a disagreement in which there are presumed areas of agreement on how to disagree. Protagoras, he maintains, “transforms the alternative into a dilemma. If Euathlus has won at least once, he must pay. If he never won, he still won at least once, and must pay” (D, 6). (“Si Evalthle a gagné au moins une fois, il doit payer. S’il n’a jamais gagné, il a quand même gagné au moins une fois, et il doit payer.”18) Reflecting further on how it can it be that Euathlus won when he always lost, Lyotard explains that Protagoras’s trick, anticipating the Russellian logical axiom of n + 1 as well as the Kantian solution of the antinomies of pure reason (in which the phrase that synthesizes the series, in being excluded from the series, opens the series to indefiniteness), is to “confuse the modum … with the dictum,” which is to say, “to use the faculty of the phrase to take itself as a referent. I did not win, and in saying it I win” (D, 6) (“Je n’ai pas gagné, je le dis, et je gagne en le disant” [LD, 20]). “A case of differend between the two parties takes place when the ‘regulation’ of the conflict that opposes them is done in the idiom of one of the parties while the wrong suffered by the other is not signified in that idiom” (D, 9). Another way to describe this is as a bait and switch, in which two orders of language rub up against each other in mutual untranslatability. As Lyotard articulates this: “Phrases from heterogeneous regimes, cannot be translated from one into the other” (D xi–xii) (“Deux phrases de régime hétérogène ne sont pas traduisibles l’une dans l’autre” [LD, 10]).

Where the differend prevails, the social field of intersubjective communication is rife with triggers and traumatic affects.19 Jordan Peele’s phenomenal comedy-horror film Get Out brings this treacherous landscape into stark relief, starting with the title. The expression “Get out!” may be understood both as a self-serving or protective command—“Get out of the way! Get out of here!,” flee, save yourself—and as a sarcastic comment: “Get out,” “Go on,” “Gimme a break,” “Stop pulling my leg.” This primal amphiboly programs undecidability into the narrative path. As in a video game, the protagonist must navigate prompts in order to survive, all the while knowing that in entering the linguistic realm of homonyms, where any single sentence contains “different plurals at one and the same time,” the slightest move of under- or overhearing brooks catastrophe.20

Get Out is an exercise in ear training—in translating the violence of aural cues embedded in the double entendre and in discerning the element of personal attack in forms of sonic address that fire their sprockets in multiple directions (it is this extra target charge that, in raising the receptor level of intensity, distinguishes listening from hearing according to Jean-Luc Nancy).21 To become “all ears” in this sense suggests prowess in the art of gaming, the possession of proprioceptive skills at averting close calls and scrapes, encounters with bad juju, traps that bring the subject within a hair’s breath of mortal danger. Here we reach another dimension of the word justesse, specifically, its adverbial usage in the French expression de justesse, meaning “cutting it close,” or “just making it.” In an afterword to Jean-François Lyotard and Jean-Loup Thébaud’s Just Gaming, Samuel Weber refers it to

the manner in which an event, an act, a thing can almost not make it, or the way in which something has a hard time making it [a de la peine à arriver], perhaps because it was cut a little close [calculé un peu juste], or because there were obstacles to overcome, barriers to get by, resistances to surmount. As in a sporting contest, or in a fight, where one can win (or lose) just by a hair [de justesse]. Or like an accident, which may have been just avoided [de justesse]. Or finally, like a text that manages to be written, but just [qui ne réussit à s’écrire que de justesse].22

In Get Out, Chris’s magic powers, which allow him to only just barely (de justesse) make it out alive from Rose’s bucolic slave-camp, are matched against the forces of failure and impotence lodged in the epigenetics of trauma, the embedded memory of maternal loss, and beyond that, the transmitted memory of slavery-wounds: indenture, enchainment, torture. Here, then, we are also embarked on tracking the effects of what Jean Laplanche, in an interview with Cathy Caruth, called the ‘“enigmatic signifier,” which draws out the obscured link, at the level of the signifier, between seduction and traumatic impact, between inscription of presence and the adult Other’s forced intrusion on the child’s psychic structure.23 In the film, there is a fully resonating chamber of these enigmatic signifiers. A knock on the door by a white woman arriving at her black boyfriend’s apartment, the thud of a deer hitting a car windshield, the chopping of wood on a stately property—all might subliminally register as the audio track of a forcible entry raid (pounded doors, battering rams, grenade detonations).24 A banal phrase attesting to the white family’s loyalty to their black retainers—“We simply couldn’t let them go”—enunciates the family’s evil reinvention of slave captivity.

An anodyne interview with a traffic cop dispatched to the scene of the car accident simultaneously reads as a performance of racial profiling:

Officer (addressing Chris): Sir, can I see your license please?

Rose: Wait why?

Chris: I have a state ID

Rose (interceding): Wait why? He wasn’t driving.

Officer: I didn’t ask if he was driving, I asked to see his ID

Rose: Yeah, why? That doesn’t make any sense. (To Chris) You don’t have to give him your ID because you haven’t done anything wrong.

Officer (with Rose chiming in): Any time there’s an incident we have every right to ask for …

Voice of backup cop over radio: Everything all right, Ryan?

Officer (to other officer): Yeah, I’m good.

Officer to Rose: Get that headlight fixed, and that mirror.

Rose (dripping with sarcasm): Thank you officer.

By exchanging the “who” (as in who was driving) for the what (his ID), the officer deploys a bait and switch, providing answers that deflect the object of the question. “I didn’t ask who was driving, I asked to see his ID.” The same device applies to the mode-flipping of “right” (as in the “right” to enforce the law) for “right” (in the sense of “being OK,” “good,” or “having the situation under control”). These effects of differential hearing surface too in the cat-and-mouse game of autocorrection being played: Rose corrects the officer on his mistaken identity of the driver, prompting the officer to correct her correction, at which point she understands that what is really not correct is the fact that she is traveling with a black passenger. What is withheld or unspoken is just as important as what is said or heard in this world of innuendo weaponized by force of law. By not asking to see Rose’s ID, by only asking to see Chris’s ID, the officer indirectly alludes to voter intimidation tactics that involve vetting minority voters who might not have the right papers. By the same token, asking to see his ID references the long history of harassment of African-Americans by traffic police, from routine incidents of stop and frisk to the murders of Sandra Bland, Samuel DuBose, and Philando Castile, all of whom were pulled over because they were driving while black.

Get Out trains a microphone on the most cringe-inducing specimens of raced speech, revealing the lowering violence within interracial dialogue. Throughout, the white people strive to prove how unracist they are, as when Rose’s father queries the couple using his grotesque mimesis of African-American vernacular speech: “So how long has this been going on, this ‘thang’?” Chris initially programs himself to under-hear such microaggressions, offering a nervous laugh or a smile in response to the white people’s self-congratulatory professions of philo-negritude: “I would have voted for Obama a third time, if I could”; “It’s such a privilege to be able to experience another person’s culture. You know what I’m sayin’?”; “Is the African American experience an advantage or disadvantage?”

Such phrases prophesy a sinister end, and audience members, acting as danger translators, have been known to scream at the screen, “Get out! Whitey’s coming for you!” But Chris is not the only character who is translationally challenged. Two black detectives, alerted by Chris’s friend Rod, prove to be similarly unable to hear how paranoia can speak the truth. As Lyotard reminds us: “Doesn’t paranoia confuse the As if it were the case with the It is the case?” (“Le paranoia ne confond-elle pas le: Comme si c’était le cas avec le: C’est le cas?” [LD, 23]). Well here, it really is the case! As one of the film’s commentators has observed: “Rod spins what seems, to the officers, like an absurd yarn: Chris is the victim of a conspiracy involving the theft of black bodies, and their enslavement. The story turns out to be all too true, and clearly evocative of past antiblack atrocities that have similarly been disbelieved, distorted, and denied. Rod is laughed at by the very people from whom he expects racial solidarity.”25

Get Out depicts how the differend, the phrase in dispute, shatters solidarities and disarms the powers of active resistance. It is only the shock of armed response—Rose’s confiscation of the car keys, the implementation of weapons and brute force by members of the family—that induces Chris to be “woke,” shaken out of the hypnotic stupor that keeps him granting white people permission to communicate their microaggressions—cuts, slights, and exclusions—under cover of civility, bonhomie, and the pretense of good intentions.

There may be some glimmer of hope by the film’s end that the soundtrack of yells and shrieks of pain associated with the long history of enfleshed black subjects of torture—what Hortense Spillers calls “pornotroping”—will convert to a score of resilience and survival, such that, as Fred Moten put it, “shriek turns speech turns song.”26 But the promise of retribution, in the guise of a justicing song that shakes reparation free from an equivocalized interpretation, remains elusive.

By the conclusion of the film, the imploding differend lays bare a battleground of untranslatability, contoured by heterogeneous regimes of hearing and response. We don’t know what is being heard up to the very last. Chris has eluded the clutches of his captors; Rose, who has tried to hunt him with a rifle, has been felled and strangled by Chris; and then there is the peal of a police siren. Armed response! Immediately we predict Chris’s downfall at the hands of the white criminal justice system. But as it turns out, the police car belongs to Rod, Chris’s guardian angel, who works in the security business as a TSA officer. Everyone in the theater laughs with relief at realizing that Chris will be spared and that the siren call was a joke on us.27 But thinking about this further, the joke is probably on the joke, which depends for its effect on the fact that you can’t, on the basis of hearing, distinguish (in a Schmittian framework) friend from enemy. Rod is, after all, an employee of the security state, part of the same apparatus of criminal justice that employed the white traffic cop who harassed Chris earlier in the film. The administration of audiometric justice is thus suspended, stranding the listener to the soundtrack of armed response in the netherworld of the judicial hearing, where one can no longer justify what one hears, nor “justice” how one responds. To translate, in these conditions, is to commence a work of judicial hearing, which attunes the ear to a violent soundtrack that defies even as it demands re-adjudication.

The text on customized signs of this sort ranges from polite (on a lawn next to a driveway in Brentwood: “Do Not Enter this Driveway! Merci.”) to grotesquely threatening (on a chain-link fence in front of a Southwest Baltimore rowhouse: “This Property Protected by Two Pitbulls with AIDS!”). Both examples provided by Neil Hertz, whom I duly acknowledge with thanks.

Peter Szendy, “(No) More Ears: A Preface to the English-Language Edition,” in All Ears: The Aesthetics of Espionage, trans. Roland Végsö (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), x.

Jean-Luc Nancy with Adèle van Reeth, Coming, trans. Charlotte Mandell (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 33.

Kevin Sack, “Door-Busting Raids Leave a Trail of Blood,” New York Times, March 18, 2017 The footage accompanying the article reveals the blurred line between policing and home invasion →.

Mladen Dolar, A Voice and Nothing More (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 3.

Plato, La République, ed. and trans. Georges Leroux (Paris: Flammarion, 2004), 581.

Daniel Heller-Roazen, No One’s Ways: An Essay on Infinite Naming (New York: Zone Books, 2017), 15–18.

Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am, trans. David Wills (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 8, 9.

Jacques Derrida, “Ants,” trans. Eric Prenowitz, Oxford Literary Review 24 (2002): 17, 20. French original: “Fourmis,” in Lectures de la différence sexuelle, ed. Mara Negron (Paris: Editions des Femmes, 1994), 69, 74.

Wai Chee Dimock, Residues of Justice: Literature, Law, Philosophy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 110, 166.

Jacques Derrida, “Justices,” trans. Peggy Kamuf, Critical Inquiry 31, no. 3 (Spring 2005): 691.

Irving Goh, “From the Editor: Prepositional Thoughts,” Diacritics 42, no. 2 (2014): 4–5.

Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening, trans. Charlotte Mandell (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007), 29, 28.

This call to “being” comes through in Pink Floyd’s song “Comfortably Numb,” which kicks off with the sound of someone knocking on a door and repeating “Time to Go,” followed by the lines: “Hello? (hello) (hello) / Is there anybody in there? Just nod if you can hear me / Is there anyone home?” The lyrics also register a dream/drug state or underwater sensation of experiencing an address that looks intelligible but whose message remains unheard: “Your lips move but I can’t hear what you’re saying.” See →.

Jacques Derrida, “What is a ‘Relevant’ Translation?” Critical Inquiry 27, no. 2 (Winter, 2001): 177.

Gustave Flaubert, Letter to Louise Colet, in The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, vol. 1: 1830–1889, ed. and trans. Francis Steegmuller (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 159.

Jean-François Lyotard, The Differend: Phrases in Dispute, trans. Georges Van Den Abbeele (Manchester: Manchester University Press). Further references to this work will appear in the text abbreviated as “D.”

Jean-François Lyotard, Le différend, (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1983), 20. Further references to the French original will appear in the text abbreviated as “LD.”

The problem of trauma, its veridical perception, fiability, and litigatability, lies at the heart of Lyotard’s endeavor. In the introductory pages of the first chapter, the differend is posed in relation to the Holocaust denials (Robert Faurisson et al.) that were raging at the time. Lyotard cites Pierre Vidal-Naquet’s response to the Faurisson affair in his Les juifs, la mémoire, et le present. Réflexions dur le genocide (Paris: La Découverte, 1981). My thanks to Hent de Vries for drawing out the connection in Lyotard’s work between the dilemmatics of differend—“Either you are a victim of a wrong or you are not. If you are not, you are deceived (or lying), in testifying that you are. If you are, since you can bear witness to this wrong, it is not a wrong, and you are deceived (or lying) in testifying that you are the victim of a wrong,” (D, 5)—and the debate in France around the existence of the Final Solution.

Jacques Derrida and Anne Dufourmantellle, De l’Hospitalité (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1997).

Nancy writes: “If listening is distinguished from hearing both as its opening (its attack) and as its intensified extremity, that is, reopening beyond comprehension (of sense) and beyond agreement or harmony (harmony or resolution in the musical sense), that necessarily signifies that listening is listening to something other than sense in its signifying sense.” Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening, 32.

Samuel Weber, “Afterword,” in Jean-François Lyotard and Jean-Loup Thébaud, Just Gaming, trans. Wlad Godzich (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 114.

Cathy Caruth, “An Interview with Jean Laplanche,” 2001 →.

Drawing out the especial significance in Nancy’s writing of the “knock,” Irving Goh offers an astute analysis of “the political implications of risking accidental knocks in ‘the risk of existing,’” as a “counterpoint to” or “‘jamming’ of” contemporary biopolitics.” Irving Goh, “The Risk of Existing: Jean-Luc Nancy’s Prepositional Existence, Knocks Included,” Diacritics 43, no. 4 (2015): 10, 19.

Glenda R. Carpio, “Going in for Negroes,” Public Books, May 23, 2017 →.

Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 22. Moten is building off of Hortense Spillers’s landmark essay “‘Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe’: An American Grammar Book” (1987), in Black, White, and in Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 203–29; and Saidya Hartman’s seminal Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997). For an important analysis of “the auditory in the operations of the cinematic pornotrope,” see Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Subject (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 106.

On the sound of the siren and the joke, see Zadie Smith, “Getting in and Out,” Harper’s, July 21, 2017 →.