Act I

Kim Jong-nam, the eldest son of former North Korean leader Kim Jong-il, was killed in an attack at Malaysia’s low-cost carrier airport, klia2, at around 9:00 a.m. on February 13, 2017. He was scheduled to take a flight to Macau later that morning. Two women, Vietnamese Doan Thi Huong (twenty-eight) and Indonesian Siti Aisyah (twenty-five), were allegedly asked to wipe baby oil on Jong-nam’s face, and were paid $90 for this reality-TV prank. However, twenty minutes after the attack—which was caught on airport security CCTV—Jong-nam was dead. The autopsy identified the “baby oil” as the deadly nerve agent VX. Several North Korean male suspects, said to have been watching when the attack was carried out, all fled the country on the same day.

Did Kim Jong-un consider his half-brother such a threat that he orchestrated this brazen remote assassination on foreign soil — one replete with all the hallmarks of a twentieth-century Cold War operation - now unfolding live on twenty-first century, twenty-four-hour rolling news and social media?

On March 1, both Huong and Aisyah were charged with Jong-nam’s murder.

Act II

Scene I

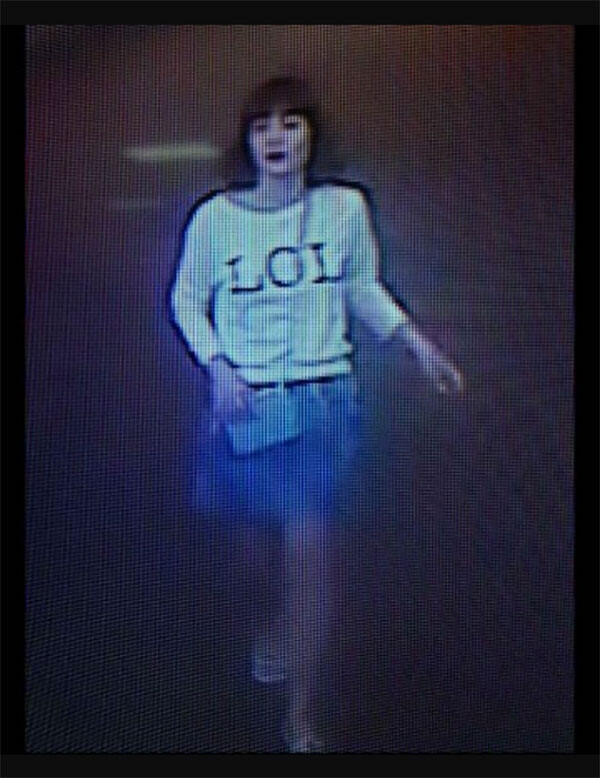

Soon after the murder, an image was publically released.

A press image issued by the Malaysian police in an attempt to publicly identify the murderer of Kim Jong-nam, son of the former North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

Clearly, it’s culled from airport CCTV: low-resolution, a casual pose captured accidentally. And, although the release of the image had prosaic purposes—informing the public of a wanted murder suspect; or crowdsourcing our eyes to try to identify her—the ghostly quality immediately gave the image an unintended life. Especially in my own retinal imagination.

I became fixated. Arrested. By this picture of a person whose biography (“Duan Thi Huong,” “twenty-eight-year-old entertainment worker,” “contestant on the Vietnamese version of American Idol,” whose last Facebook post said, “I want to sleep more but by your side”) mattered way less than her “LOL” long-sleeve tee and ethereal gait.

The picture possessed worth. It felt like one of those self-contained images that history delivers to us and, reciprocally, delivers history. Images that feel both inscribed in the time they are from, and yet also equally out of time.

A ready-made.

A thousand things come to mind when I gaze at this image: firstly as a whole, then, increasingly, as a constellation of fragments.

Scene II

I was compelled to print it out. I zoomed into specific parts—her face, her hands, the bag she’s clutching, the dark corona of her eyes, that flat, flat fringe—and printed these out too. I used Photoshop and Mac’s Preview to enlarge the image, each time degrading resolution. Then, I’d photograph the printouts. Zoom in more. Print out again. Fidelity felt unimportant compared to some auratic essence. Locked in the glow of the pixels.

Scene III

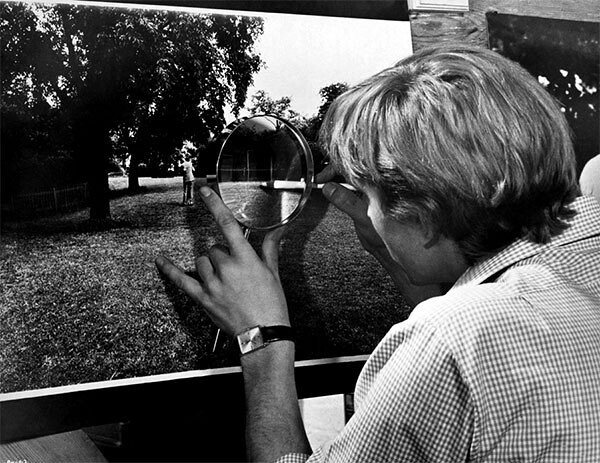

A man’s fetish of zooming into photographs appears in the film Blow Up (1966), directed by Michaelangelo Antonioni, based on a short story by Julio Cortázar. The more photographer Thomas “blows up” a single frame to locate a murder, the less sure he is that the camera did, in fact, witness a murder. The camera’s claim to truth, in that perplexingly Heisenbergian sense, is made all the more uncertain when human faith invests in it.

‟A man’s fetish of zooming into photographs appears in the film Blow Up (1966), directed by Michaelangelo Antonioni, based on a short story by Julio Cortázar.”

A year later, and Michael Snow’s Wavelength extended a single zoom shot of a single room to become the entire forty-three minutes of his seminal film.1 It is almost tediously teleological. And though we may end upon the photo pinned to the wall of waves in the sea, we may also have missed a dead body that flashes for merely a brief moment somewhere between. Snow suggests that our yearning for forensic truth may be found not at the extremes, but in the incidental middle ground, where our attention is least attentive.

Scene IV

Other postproduction tropes are contained in Duan Thi Huong’s digital portrait: Andy Warhol’s reportage car crashes and electric chairs. Or Robert Rauschenberg’s pilfering of newspaper photos into aestheticized pin-ups. Or David Hockney’s Polaroid mosaics from the early 1980s, which lenses Cubism via cheap consumer camera format.

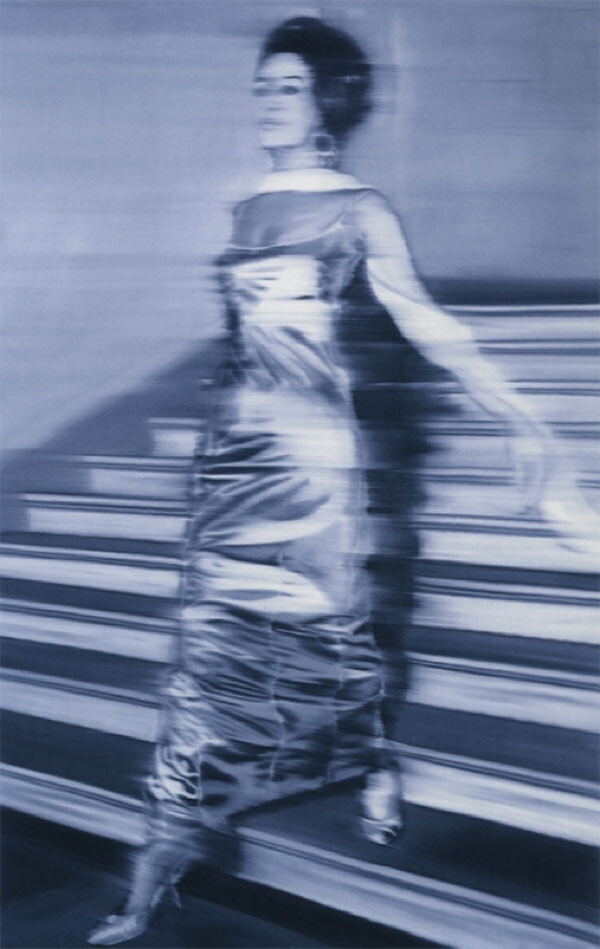

Duan Thi Huong’s body floats in the darkness of her image, equally glowing, and also dissolving, like smeared data. That auratic glow may simply be what happens when sophisticated technology colludes with its own technical limits. But it’s also the glow found in some of Gerhard Richter’s best-known paintings of women. The inferred illumination of technology’s soul. The substance Roland Barthes mourned in his elegy to his dead mother, Camera Lucida (1980).

Gerhard Richter, Woman Descending the Staircase (Frau die Treppe herabgehend), 1965. Oil on canvas

198 x 128 cm (79 x 51 in.). Roy J. and Frances R. Friedman Endowment; gift of Lannan Foundation, 1997.

The impasto paste around Duan Thi Huong also invokes the charged zones encircling Willem de Kooning’s Women: vortices of matter, history, horror. Except in Huong’s case, the horror is emblazoned in the letters “L,” “O,” and “L.” This way, her image carries its own punch line, which seems so mordantly—or is it courageously?—at odds with cold-hearted killing.

Still from “The Assassination of Mahmoud Al-Mahbouh” video released on YouTube, 2010.

Scene V

In 2010, Hamas official Mahmoud Al-Mahbouh was killed in room 230 of the Al Bustan Rotana Hotel, Dubai. A month later, the Dubai Police held a prominent press conference. They released a video composed of footage from hundreds of surveillance cameras in Dubai’s airports, malls, and hotels. It traces the assassination to Israeli Mossad agents, and claims that at least twenty-six suspects were involved in this highly orchestrated operation. The video was broadcast on Gulf News TV and soon uploaded on YouTube.2 It became a piece of forensic entertainment, almost, albeit one that ends with a real dead body. Soon after that, Chris Marker détourned this video by adding a haunting string composition written by Henryk Górecki for the Kronos Quartet. He titled it Stopover in Dubai. It too was made available on YouTube.3 A twentieth-century espionage caper on a twenty-first-century distribution network facilitated by algorithmic face-recognition technology, in which Israel is often said to lead the world. Indeed, Facebook acquired Face.com in 2012, an Israeli face-recognition group, which had been supplying its technology to Facebook for years.4

Scene VI

In a BBC documentary about him, the author Don DeLillo spoke about the genesis of one of his novels, Mao II (1991).

It was April 1988 and the cover of New York Post featured an elderly man, in shock and rage. The man was the reclusive writer J. D. Salinger, and this was the first picture of him since 1955. DeLillo kept hold of the picture. Six months later, DeLillo came across a grainy image of a mass wedding conducted by Reverand Sun Myung Moon, from the Unification Church, which looked to DeLillo like “a rehearsal for the end of the world.” He saved this picture too. Later, DeLillo reveals, “I began to understand the novel as an attempt to understand the connection between these two photographs.”5

Act III

Scene I

If our memories are becoming more like the data sets used by Facebook et al. for facial recognition, then it’s perhaps unsurprising that our eyes and ears have become search engine interfaces.

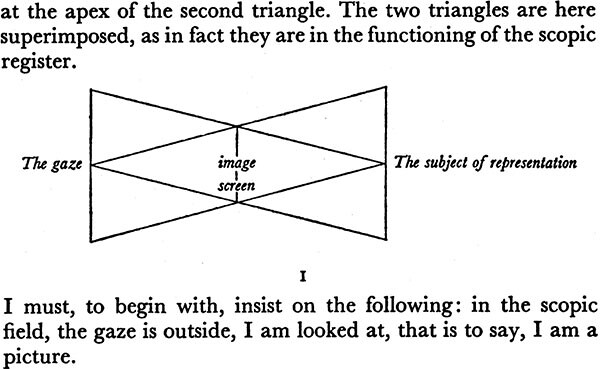

As I continue, till today, to zoom into the image of Duan Thi Huong, searching for something that beauty masks and reveals, I remember the seductive “gaze diagram” by Jacques Lacan.

“I am a picture,” Lacan says. Today, are we not pictures? Billions of them, packets of electrical pulses, pinged between you and me, via machines learning to see things we never will, through deep-sea cables and actual arteries?6 Forever circulationing?7

“Can one be as lovely as an image?” asks Catherine Belkhodja in Chris Marker’s 1997 documentary and CD-ROM, Level Five.

Scene II

Duan Thi Huong’s face is certainly not “LOL.” It is more nonchalant, closer to carefree. A skip in her step. A bounce in her stride, as if to say, “today is a great day.” Once again, it is a face I’ve seen elsewhere. The same face on countless different women who Chris Marker would shoot—among them, Alexandra Stewart, the narrator of his film Sans Soleil (1982)—whereby the gaze coming from the image refused to entirely meet the gaze going into it. There’s beauty, of course, but more strongly, tender isolation.

The thing is: something always exceeds the images of faces. Escapes complete capture. Maybe it is why we take so many selfies everyday?8

See →.

See →.

See →.

“Facebook buys Israeli facial recognition firm Face.com,” BBC News, June 19, 2012 →.

See →.

See Trevor Paglen, “Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You),” The New Inquiry, December 8, 2016 →.

See Hito Steyerl, “Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?” e-flux journal 49 (November 2013) →.

See →.