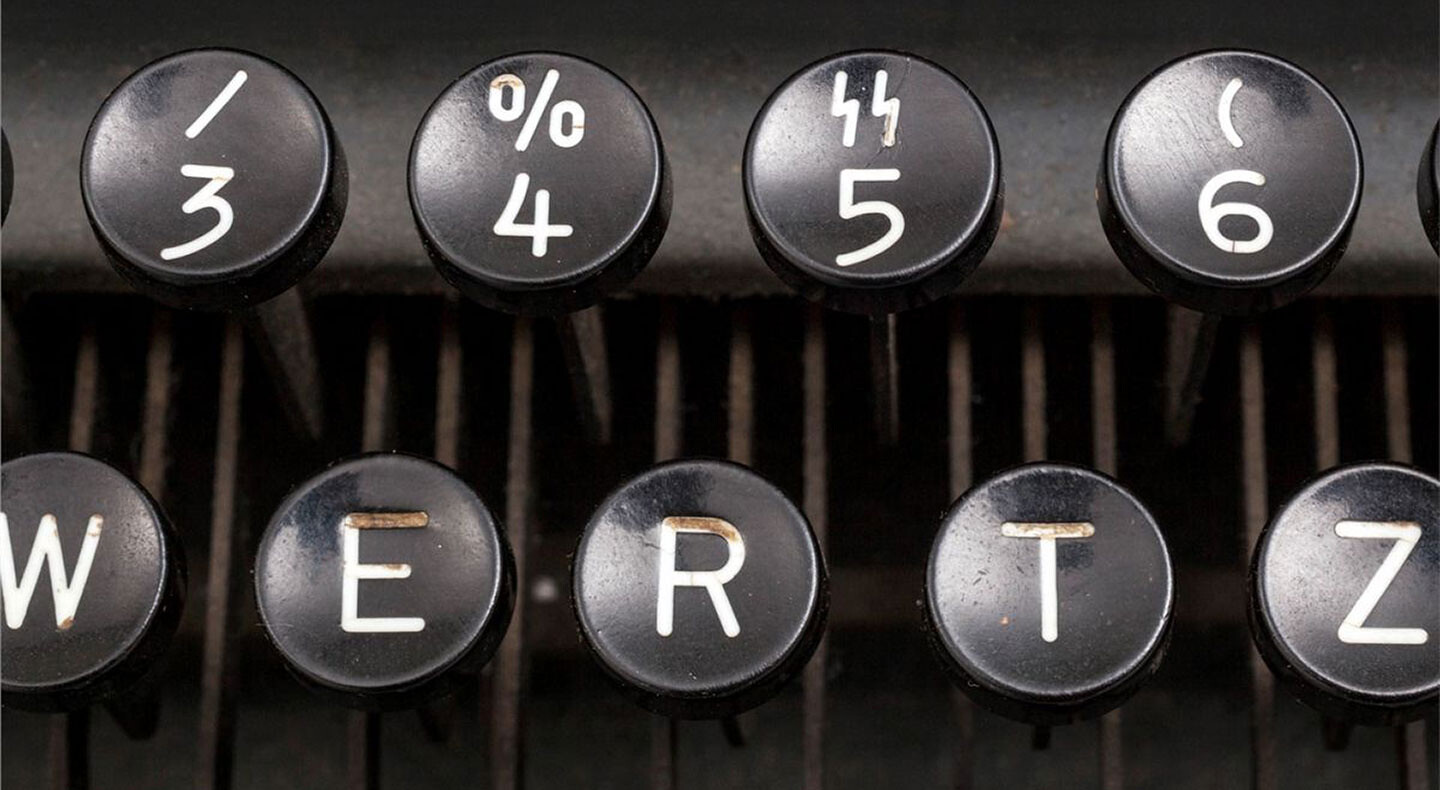

Following the defeat of Nazism, Victor Klemperer, a Jewish philologist and professor of romance studies, published LTI—Lingua Tertii Imperii: Notizbuch eines Philologen, a series of linguistic insights based on diaries kept under a certain imperative: “observe, study and memorize what is going on—by tomorrow everything will already look different, by tomorrow everything will already feel different; keep hold of how things reveal themselves at this very moment and what the effects are.”1 Translated into English as The Language of the Third Reich, Klemperer’s astonishing analysis of the language of Nazism, and his account of what it took to survive the genocidal regime, remains the template for any future understanding of the role that language plays in reactionary and fascist times. “Language reveals all,” Klemperer writes.

The most powerful influence was exerted neither by individual speeches nor by articles or flyers, posters or flags; it was not achieved by things which one had to absorb by conscious thought or conscious emotions. Instead Nazism permeated the flesh and blood of the people through single words, idioms and sentence structures which were imposed on them in a million repetitions and taken on board mechanically and unconsciously.2

Under the New Brutality, we may wonder what the words, idioms, and sentence structures of our own times might be, what “tiny doses of arsenic” we are swallowing, which words have changed their values, which words have disappeared, how the way we speak and write is changing, and with what detrimental effects.

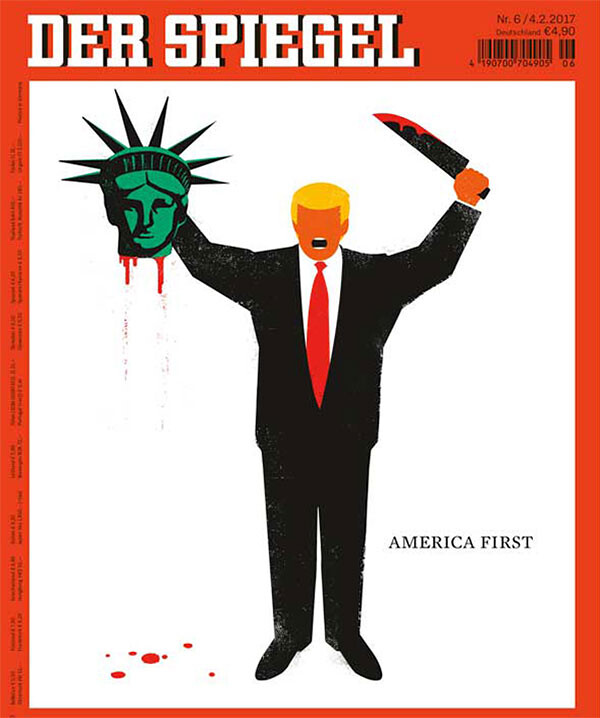

Der Spiegel’s viral cover from February 2017 features Donald Trump beheading the statue of liberty, drawn by Cuban-born American illustrator Edel Rodriguez. Both Der Spiegel and Time Magazine have since worked with Rodriguez.

Klemperer describes the language of the Third Reich as no longer drawing a distinction between spoken and written language, such that “everything was oration, had to be address, exhortation, invective.”3 Fanaticism becomes a virtue. While the rally, the talk show, the shock jock, and the tabloid smear all exhibit these features, the internet provides us with another avenue of investigation. If spoken and written language continue to be blurred, such that every Trump tweet is indistinguishable from something he might equally well say aloud (“Getting ready for my big foreign trip. Will be strongly protecting American interests—that’s what I like to do!”), we can also describe the blurring of the distinction between written language and the image in the form of the meme. Klemperer indeed noted that “the entire thrust of the LTI was towards visualization.”4 The internet meme, and a peculiar form of sly, ironic, vicious humor, have become part of our new linguistic and imagistic reality. Where Klemperer noted that the LTI was “impoverished and monotonous,” the language-images of the New Brutality are ambiguous and uncertain.5 They spill over from screen to street, from GIF to poster, from the anonymity and snark of forums to the murderous, smirking bloodlust of rallies, and the deadly attacks of supremacist individuals: “Until recently, it would have been hard to imagine the combination of street violence meeting internet memes … The ‘alt-right’ have stormed mainstream consciousness by weaponizing irony, and by using humour and ambiguity as tactics to wrong-foot their opponents,” writes Jason Wilson.6 Angela Nagle, long-term documenter of the alt-right and online culture, similarly describes a terrifying future:

The emergence of the Alt-right should warn us of a now imminent nightmare vision of what the coming years might hold—a public arena emptied of any civility, universalist ideas or openly competing political visions beyond a zero-sum tribal antagonism of identity groups, in which the boundaries of acceptable thought will shrink further while the purged will amass in the fetid forums of the Alt-right.7

The neoliberal project to destroy the public sphere meets the hate networks of the internet, and it is these “identity groups” who will, unless things change radically, take to the streets: these spaces now also made to be places of ambiguity—privatized, unevenly securitized and surveilled—where IRL is increasingly constructed by virtual belongings.

Pepe the Frog loses his head.

What is the language of this ambiguous, violent tendency? It comes from online of course—from pornography, from casual and relentless insults, words that utterly demean and belittle. To focus on a particular word from this lexicon, perhaps an overly obvious one, that sums up the racist, sexist, vicious tendency of the language and imagery of the New Brutality, one need look no further than the word “cuck.” From the old French word for “cuckoo” (“cucu”), this go-to insult captures a whole host of overwhelmingly male anxieties. In porn, a cuck is someone who stands by while his female partner has sex with another man (often black). In its current usage (sometimes expanded to “cuckservative”), the original meaning is preserved and politicized: cucks are effeminate conservatives who concede to liberal values, “emasculated” by their own cowardice and enjoying their own degradation. To be a “cuck” is to be screwed over, a victim of women and other men, sexually and economically. A recent post on the Anarcho-Capitalism subreddit asked:

Is having daughters the ultimate cuckoldry?

I cannot think or comprehend of anything more cucked than having a daughter. Honestly, think about it rationally. You are feeding, clothing, raising and rearing a girl for at least 18 years solely so she can go and get ravaged by another man. All the hard work you put into your beautiful little girl—reading her stories at bedtime, making her go to sports practice, making sure she had a healthy diet, educating her, playing with her. All of it has one simple result: her body is more enjoyable for the men that will eventually fuck her in every hole.

Raised the perfect girl? Great. Who benefits? If you’re lucky, a random man who had nothing to do with the way she grew up, who marries her. He gets to fuck her tight pussy every night. He gets the benefits of her kind and sweet personality that came from the way you raised her.

As a man who has a daughter, you are LITERALLY dedicating at least 20 years of your life simply to raise a girl for another man to enjoy. It is the ULTIMATE AND FINAL cuck. Think about it logically.8

Predictably, confusion reigns as to whether the poster is sincere or trolling, and whether the text is “copypasta” (cut and pasted, often with trollish intent) from some other place. But whatever the intent of the original poster, this outline sketch of the “ultimate and final cuck,” apart from filling the reader with revulsion, indicates the logical outcome of a certain mentality, and a certain language. If your major fear is of another man having sex with a woman you believe to be your property, be it your wife, your partner, or your daughter, and if this fear and suspicion is all-consuming, you will be easily manipulable if and when entire groups are portrayed as ready to “cuck” you over. The language of contemporary fascism is the language of victimhood—who would ever want to be a cuck? Better get the insult in quick—and the fear of victimhood: “A major taproot of the LTI is embedded in the resentment and aspirations of disappointed professional soldiers.”9 “Cuck” is an emotional term masquerading as an insult, a clear case of simple projection: insult the other before he can undo you.

A “Cuckservative” sticker is spotted outside of the White Boy Internet (WBI) and in real life (IRL).

Klemperer did not try to analyze the unconscious of the LTI so much as its material surface and the emotions it played with: “New words keep turning up, or old ones acquire new specialist meanings, or new combinations are formed which rapidly ossify into stereotypes.”10 Language is miasmic (“some kind of fog has descended which is enveloping everybody”).11 Klemperer tells a little story that encapsulates, in ways that bring tears to the eyes, the horror of inevitable compromise and complicity:

I am reminded of the crossing we made twenty-five years ago from Bornholm to Copenhagen. In the night a storm had raged accompanied by terrible seasickness; but soon one was sitting on deck under the beautiful morning sun, protected by the nearby coast, in a calm sea, looking forward to breakfast. At the end of the long bench a little girl stood up, ran to the deck rail, and threw up. A second later her mother, who was sitting next to her, stood up and did the same. Almost at once the gentleman next to the lady followed suit. And then a young boy, and then … the movement worked its way steadily and swiftly along the bench. No one was passed over. At our end we were still far away from the blast: it was observed with interest, there was laughter, there were mocking expressions. And then the vomiting got closer and the laughter subsided, and then people were running towards the rail from our end. I looked on attentively and observed myself closely. I told myself that there is such a thing as objective observation, and that I had been trained in it, and that there was such a thing as a firm resolve, and I looked forward to breakfast—and at that point it was my turn and I was forced to the rail just like all the others.12

We are memetic creatures. Images and words are damaging. We do not need to look for complex reasons why irony and ambiguity have become stand-ins for fascist feeling of all kinds (misogyny, racism, Islamophobia, homophobia). If we try to analyze the supposed unconscious motivations of the contemporary, particularly with a view of understanding and thus preventing contemporary forms of fascism, we run the real risk of understanding nothing. Klaus Theweleit, whose 1977 Male Fantasies brilliantly examines proto-Nazi Freikorps fantasies, particularly those concerning women, highlights the danger of assuming that one is talking in the right way about the fascist unconscious:

Whenever the word “communism” is mentioned in our sources, not as the collective organization of social production but as a fear of being castrated by a sensuous woman armed with a penis, its usage is so overt and deliberate that, as far as I’m concerned, we really can’t talk about an unconscious displacement, or an unconscious fear. On the contrary, it strikes me that concealing the kinds of thoughts we’ve been discussing, the ones traditional psychoanalysis would call “unconscious,” is the last thing on earth those men would want to do. They’re out to express them at all cost. The “fear of castration” is a consciously held fear, just as the equation of communism and rifle-woman is consciously made.13

It may well be that what we are looking for and looking at lies hidden in plain sight, and that we should take people at their word. Indeed, Nagle suggests this is the best approach: “Journalists should be saying, ‘I don’t want to talk about Pepe memes and hand signs. Tell me what are the limits of what you’re prepared to do.’ We should force them to talk about what they really stand for.”14 What “they” really stand for is the murder of people who attempt to stop the abuse of Muslim women on public transport; the burning of mosques, violence against women, the shooting up of churches, ethno-nationalism, the killing of unarmed black men in the streets, and getting away with murder. The irony of anonymity deployed by the alt-right is not a complex literary form, but rather the nihilism of the shrug and the violence of the mob, a conformity to nonconformity. As Luke Winkie puts it in an article explaining how he used to be a “teenage troll”:

4chan and other sectors of the White Boy Internet are a safe space for privileged animosity. It’s the only place an ignorant white boy can go and be right, even when they’re wrong. They can live out the fantasy, embrace the rage, and pool their frightened bitterness into something that feels righteous.15

From the LTI to the WBI … Theweleit makes it clear that much is on the surface: “Until now, it seems, fascists themselves have been questioned too little about fascism, whereas those who claim to have seen through fascism (but who were unable to defeat it) have been questioned too much.”16 The “frightened bitterness” of the White Boy Internet has become the self-appointed army for Trumpism, and for many forms of contemporary violence. When they say they are worried about having their dick cut off, or “their” women taken from them, or their spaces and obsessions “infiltrated” by women and “nonwhites,” they mean it. White supremacist Jeremy Joseph Christian, who recently murdered two men who stepped in to stop his racist tirade against a Muslim woman and her friend on a train in Portland, Oregon, was reportedly obsessed with circumcision, writing on his Facebook page that he wanted a job in Norway (based on his fantasies of Vikings and racial purity) “cutting off the heads of people that circumcize babies.”17 This double decapitation imagery is not coincidental. Beheading, whether the literal cutting off of the head, and/or the fear of castration, is at the heart of our understanding of Western representation, leading us right back to our concern with images and words, and word-images. As Kristeva puts it in The Severed Head,

To represent the invisible (the anguish of death as well as the jouissance of thought’s triumph over it), wasn’t it necessary to begin by representing the loss of the visible (the loss of the bodily frame, the vigilant head, the ensconced genitals)? If the vision of our intimate thought really is the capital vision that humanity has produced of itself, doesn’t it have to be constructed precisely by passing through an obsession with the head as symbol of the thinking living being?18

Beheading is, in some sense, the ultimate image of violence, and we must think through it if we are to survive the New Brutality.

Kathy Griffin’s self-portrait with a bloodied Trump mask heavily references the art historical iconography of Salomé with the severed head of Saint John the Baptist. The scene is depicted here in a 1530 painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The language of the New Brutality is a primal, irrational language, which is at the same time desperately fearful of the double decapitation. Videos of beheadings exist in some ambivalent internet terrain and are permitted, then banned from Facebook (unlike female nipples, which are always banned). Objects of fascination, recruitment, and warning, video footage of beheadings lurk behind representation as such. Pity the Facebook moderators whose eyeballs have to scan and screen, day after day, working under guidelines like “remarks such as ‘Someone shoot Trump’ should be deleted, because as a head of state he is in a protected category. But it can be permissible to say: ‘To snap a bitch’s neck, make sure to apply all your pressure to the middle of her throat,’ or ‘fuck off and die’ because they are not regarded as credible threats.”19 The cartoon image of Trump decapitating the Statue of Liberty on the front of Der Spiegel in February this year caused outrage, despite its distancing style.20 Comedian Kathy Griffin recently had to plead for forgiveness after holding up a bloodied, “beheaded” Trump mask in a photograph. We cannot think clearly about what these images are doing because they are so tied up with the limits of seeing as such—what we desire to see, how we desire to desire, and what exists at the limit of both how and what we see: our ways of seeing are tinged with horror. But we need philosophizing more than ever: “the exercise of reason, of logical thought, something which Nazism views as the most deadly enemy of all.”21 But whose reason? The alt-right may not believe that what they are doing is “rational,” but they certainly think that they are a lot more reasonable than the “social justice warriors” they oppose, and that tactics of irony and scorn are ways of undermining perceived irrationalisms on the part of the liberal left. We need to think much more carefully about the word-images that surround us, to make distinctions between the way violence is described and presented, and not think that all images are equally interchangeable. We need to remember all the words and ways of speaking we have forgotten, and note the way in which certain words, such as “cuck,” come to dominate our ways of speaking and thinking. We need to remain, not with Trump’s idiotic exclamation mark, but with the question mark, “the most important of all punctuation marks. A position in direct opposition to National Socialist intransigence and self-confidence.”22

Above all, we need to think about the relationship between representation and violence, whether we focus on decapitation or otherwise. “There are very few circumstances in which it is editorially justified to broadcast the moment of death” says the BBC’s editorial guidelines for its news and current affairs shows.23 So our image of the moment of death is largely fictional, unless we seek out “authentic” videos of decapitation. Why might we feel compelled to do so, or to think about them if we, the lucky ones, have the choice of whether to watch them or not? I do not rightly know, other than for what it can tell us about the fears that structure the language, images, and actions of the New Brutality. It is only through our collective thinking, our general intellect, opposed both to the solitary head of the sovereign state and to the hot-headed fears of violence that generate yet more violence, that we can understand how it is possible to think at all today, and to be careful not only with words and images, but also with each other.

Victor Klemperer, The Language of the Third Reich: LTI—Lingua Tertii Imperii: A Philologist’s Notebook, trans. Martin Brady (London: Bloomsbury, 2013 (1957)), 10.

Ibid., 11, 15.

Ibid., 22.

Ibid., 74.

Ibid., 20.

Jason Wilson, “Hiding in Plain Sight: How the ‘Alt-Right’ is Weaponising Irony to Spread Fascism,” The Guardian, May 23, 2017 →.

Angela Nagle, “What the Alt-Right is all about,” Irish Times, Jan 6, 2017 →.

See →.

Klemperer, The Language of the Third Reich, 28.

Ibid., 29.

Ibid., 38.

Ibid., 39–40.

Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies, Vol. 1: Women, Floods, Bodies, History, trans. Stephen Conway in collaboration with Erica Carter and Chris Turner (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987 (1977)), 89.

Angela Nagle, quoted in Wilson, “Hiding in Plain Sight.”

Luke Winkie, “I was a teenage 4chan troll—until I learned to change my ways,” Daily Dot, August 26, 2015 →.

Theweleit, Male Fantasies, 90.

Jason Wilson, “Suspect in Portland double murder posted white supremacist material online,” The Guardian, May 28, 2017 →.

Julia Kristeva, The Severed Head: Capital Visions, trans. Jody Gladding (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 4.

Nick Hopkins, “Revealed: Facebook’s internal rulebook on sex, terrorism and violence,” The Guardian, May 21, 2017 →.

“German magazine defends cover showing Trump beheading Statue of Liberty,” Reuters, February 5, 2017 →.

Klemperer, The Language of the Third Reich, 147.

Ibid., 74.

“Violence in News and Current Affairs: Summary and Guidance in Full,” bbc.co.uk →.