Artist as Consumer

Artists like to role-play scenarios in order to max-out concepts to their logical ends. Art is the space where practices that cannot function within generic constraints run up against the walls and expose fissures in the structures they are working in. Think of documentary or narrative films that don’t quite cut it in a mainstream film context, or technologies that fail as commodities but succeed as concepts. When understood as art, these are allowed to exist in all of their complexity.

As an art student in the late aughts, my professors propagated the fantasy that alterity provided access to an otherwise of multinational capitalism. Armed with identities shaped when an “outside” or “another world” was possible, they maintained that the other is always outside, and always subversive to “dominant” culture. With practices emerging in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, punk negation, slacker refusal, institutional critique, and art-as-activism were put forth as viable tactics for resistance. But to my cohort, the proposal of simple opposition over immanence did not feel appropriate or effective in resisting the conditions of our moment; it felt romantic. A strategic sense of imbrication seemed to better address the layered complexities of the reality at hand. By 2008, institutional critique was being taught as a historical practice. What had once been radical—even, with Buren and Haacke, to the point of censorship—had now been wholly recuperated. As Hal Foster pointed out a decade earlier, the “quasi-anthropological artist today may seek to work with sited communities with the best motives of political engagement and institutional transgression, only in part to have this work recoded by its sponsors as social outreach, economic development, public relations … or art.”1

My sculpture class gathered weekly to collectively cook meals. This exercise, led by an exemplary relational aesthetics artist, quickly devolved into performative class warfare, with students bringing everything from Balthazar bread to discount produce, resulting in mixed feelings of guilt, shame, ambivalence, and inadequacy. This was at Columbia. At neighboring institutions, there was a painter known for his Beuysian performance paintings made with heritage pork fat from the Berkshire pigs he raised upstate. In Frankfurt, there was a German painter who apparently ate glass. This education championed the model of “artist as x,” or artist as performing a role—whether it be artist as cook, artist as bad boy, artist as gentleman farmer, or artist as sociopath—from a position of critical distance. Similar to homo economicus, the primary function of “artist as x” is to utilize and leverage all possible identities, situations, and social relations for their own benefit. From this accumulative imperative emerged practices where every bender was a durational performance and every broken bottle an artifact of critical engagement. Out of this educational model came Times Bar and New Theater in Berlin, the vitriolic blog Jerry Magoo, and, in my own case, a trend-forecasting group named K-HOLE. Relational aesthetics began to look a lot more like aspirational aesthetics, through the aestheticization of trolling, waste, usage, consumption, and the role played by “artist as consumer.”

Business LARPing

To some, art is also an excuse to do things poorly. If an experiment fails, calling the process and its ruins “art” becomes a contingency plan. If an experiment in a structure traditionally considered as being outside of the boundaries of art succeeds, as functional business enterprises in entertainment, tech, food, or fashion, or the murkier realms of logistics or import/export operations, it is acceptable for the experiment to exist as the thing itself. In the case of the failed, or dis-functional, commercial venture as art, the failure can be understood as performed criticality; it reveals delineations otherwise invisible and shows how the mechanisms of commerce function behind the curtain. But, regardless of success or failure, it has become expected practice to leverage the context of art for the purposes of cultural legitimacy and capital. Many successful business ventures were born this way, from restaurants and fashion labels to BuzzFeed and Kickstarter.

There is an ever-expanding gray zone where groups and projects seek to operate as commercial ventures outside the art world proper while retaining the cultural context from which they came. Cynicism reads this retention purely as cultural capital instrumentalized towards individual ends. Generosity counters that these artists seek to support their community through heightened collective visibility and towards collective ends. Art-world institutions and curators want to stake a claim on the success of these ventures. Including commodity-based, art-adjacent practices in their programs nods to an opening up and democratization of otherwise exclusive, closed institutions. This can be seen in the emerging model of pop-up shop as group exhibition, or the recent inclusion in biennial exhibitions of fashion labels that do not self-identify their brands or businesses as expanded art practices. These groups are faced with split identities: they are seen by the IRS as small-business owners and operate as such, while also being seen as producers of culture through commercially sold commodities—differentiated from “art objects.” A third identity of “artist as fashion designer, technology and food importer, or alcohol producer” is not added to the mix, because any critique aimed at the broader violence of capitalism is not being made from within the world of art, but from that of “basic” consumer-oriented commerce, albeit “aspirational” lifestyle commerce. By refusing to identify as artists, these groups resist the recuperation of this identity by start-ups, creative agencies, and real-estate developers that value creativity and “disruption.”

This turn towards commercial, commodity-driven practices arrives as the value of art objects becomes ever more abstracted and contingent on densely imbricated social, institutional, and cultural reticulation. As immaterial artistic practices are both rewarded with seven-figure sales and called out by alt-right conspiracists as satanic practices of the liberal elite, the ancient ritual of making an object of basic utility for the purposes of transparent exchange begins to promise relief. The commodity in itself offers a level of commercial purity that feels, to some, less complicit or exhausting than the highly mannered and baroque tapestry of brand narratives and leveraged networks on which creating and exhibiting even traditional forms of contemporary art—like paintings, sculptures, or photography—have come to rely. Certainly many of the groups that produce such commercial commodities continue to lean on a community of friends or a city-specific scene for visibility and cultural legitimacy, but at least these are peer networks, contrary to the inter-generational hierarchy that flourishes in the market-resisting art silos nestled in our educational institutions with HR oversight.

Seamless Web

A factor in this turn within art is the nostalgia for an era before branding, taste, and cultural context became the primary factors by which artistic production is evaluated. These commodities can claim a materialist and modernist approach, where the value of the object is ostensibly inherent in the object itself. Value derives from craft and quality or an ability to satisfy a specific need rather than from exhaustive references to context and constructed narrative. These commodities in themselves gesture to the democratization of art, through relative affordability and accessibility when released as consumable goods, design objects, and clothing. It is a functionalist approach that values art for its usability and ability to seamlessly incorporate itself into daily life. This approach to art is not meant to create rupture or to jockey speeds and tempos in its consumption. These objects do not strive to open up a chasm, and they do not call into question their own objecthood. They do not produce moments of unease that, when phenomenologically approached, lead the viewer/consumer to question their own inhabitation of a body and occupation of space. Rather, they are meant to replace the other commodities that previously occupied that space in the consumer’s lives. Why wear a Supreme shirt when you can wear a Some Ware long-sleeve? Why buy Crofters or Smuckers when you can eat Sqirl jam? Why drink Absolute or even Tito’s when you can drink Material Vodka and Enlightenment Wine? Why use a Brita when you can filter your hormone-laden municipal water through a Walter Filter? In this sense, there is a perceived ethics to consuming these commodities: you are supporting a community of artists—or artists functioning as small businesses. You may not be able to afford a painting, but you can afford a sweatshirt, and chances are, the producer of that sweatshirt doesn’t pay their gallery commission. But this provokes the question of whether these profits benefit the artist’s lifestyle, artistic practice, or the cause nodded to in the sweatshirt’s logo or brand name (see: Election Reform, or The Future is Female). The artist-as-shirt-producer will likely spend more time sourcing sustainable materials and investing in fair-labor practices than the artist who creates work out of petrochemicals with the help of their unpaid interns. Many of these practices retain their position within the art community by operating under a FUBU ethos (For Us By Us), wherein a brand produces specifically for, and for the benefit of, a community of peers, with the aim of providing financial capital, visibility, and broader legitimacy for the group. But within the context of art, these commodities transform viewers into direct consumers. The shirt, the jam, and the vodka function simultaneously as signifiers of taste and signifiers of belonging. While they might not get you thinking about objecthood and phenomenology, they will get you thinking about community and identity.

Retail Apocalypse

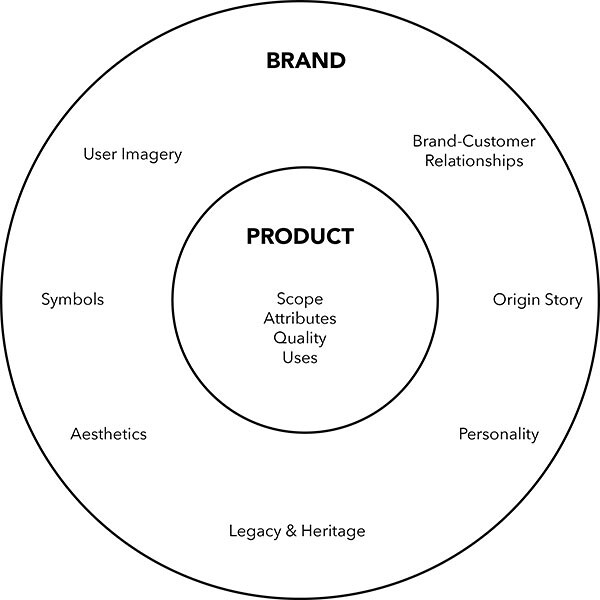

The nostalgia inherent in this commodity-driven practice is mirrored on a mass-produced, national scale, in that companies selling these commercial goods cannot sustain themselves solely on the sales of products without inflating their value through branding and context. If a business seeks to sidestep this, they instead rely on the distribution networks and logistical convenience of human powered, but soon to be automated, fulfillment centers. This allows a level of anonymity for the importer or small-business owner who is shuttling goods between mass producer and anonymous consumer via branded distribution networks like Amazon Prime. But at either level, brand value is what accounts for the difference in price between two instances of the same commodity. Often, the cheapest commodity is also the one with the least identity. A lesson learned from pharmaceuticals: generics can be bought at a lower price. The more expensive drug is branded, trademarked and I.P. driven. Branding allows for the mass production of slightly less authorless objects.

Abandoned American malls are postcard images for deindustrialization and the bottoming out of an upwardly mobile middle class. Retailers are transitioning to e-commerce-only models that rely on fulfillment centers serviced by low paid invisible labor and customer service chatbots, virtual agents and AI assistants with names like Nadia, Twyla, Tara, Polly, and Alexa. Brick-and-mortar stores have come to function as pop-up showrooms and concept spaces. Today, profitable commodities are largely those that trade in the invisible—rooted in financial trading, service, intellectual property, and culture. In other words, profitable commodities aren’t commodities at all, but assets and capitals.

Naked and Afraid | K-HOLE

In 2010, shortly after leaving school, four friends and I self-identified as cultural strategists and created a trend-forecasting group named K-HOLE. “Cultural strategists” seemed broad enough to encompass all of our practices (artist, writer, musician, filmmaker) and whatever else we might eventually mutate into, while internalizing how brands and agencies were likely to perceive our position as twentysomethings in New York City. A K-hole is what happens when you take too much ketamine, a veterinarian tranquilizer and party drug popular before our time in the ’90s. Ketamine provides the sensation of having an externalized view of your body and situation. It is like you are your own puppet master, whispering words in your ear and then hearing them spoken by a disembodied version of yourself. It is similar to an out-of-body experience, but with less of a bird’s-eye view and more of an over-the-shoulder lurk. This sense of having distance from and perspective on your situation is, of course, illusory—you’re just high. The rationale behind using K-HOLE as a name was that we did not claim to have any macro view of the landscape we inhabited as artists, writers, and twentysomethings in postrecession, pre-Occupy New York City.

The project grew out of a frustration with an attitude common among Gen X artists, who liked to neg on younger artists for not keeping their distance from the inner workings of capitalism—for “selling out.” Like our professors, artists who were a generation older than us promoted subcultural tactics such as zine-making and abject performance, which had since been aestheticized and recuperated by mainstream brands from Urban Outfitters to IKEA to MoMA. They acted as if our decision to engage was motivated by anything other than awareness of the immediacy of recuperation, survivalism, and the deep-rooted anxiety brought on by the recession and student debt. We resented the unspoken mandate within the art world that there are only certain “acceptable” jobs for an artist: assistant, teacher, physical laborer, bartender, retail worker, food service worker. As if these positions allowed artists to retain their identity as artists. You could be a singular artist, without having to confront the complexity of an imbricated identity, as long as you worked for another artist, at a boutique that happened to sell artists books and editions, or at a restaurant frequented by art-world luminaries. Beyond propagating the model of the monolithic artist, who creates their artwork uncompromised by other forms of labor, this model normalizes independent wealth and excludes those who feel poor, disenfranchised, and generally alienated when confronted with class disparity. When compounded with other occupations, the identity of an artist requires qualification—which often becomes the qualification “artist as ethnographer” or “anthropologist,” thus claiming the position of both observer and performer, and maintaining a critical stance within that role. The disappearance of salaried positions, lack of access to affordable health care as a freelance worker, lack of access to affordable housing, and student debt led me to wonder what kind of critical distance one can have in a survivalist state.

With K-HOLE, we were not interested in taking on the role of ethnographer or performer; we were interested in the total collapse that comes with being the thing itself. So, rather than perform “artists as trend forecasters,” we produced trend reports like those that are sold via subscription for tens of thousands of dollars to corporate clients and advertising agencies. We created the publications in a form we thought would circulate as freely and fluidly as possible—PDF. Unable, perhaps, to fully shed our training in market confrontation and antagonism, we saw the fact that our report was free as an affront to the traditional trend-forecasting model of groups such as WGSN, Stylus, or the Future Laboratory. What we didn’t realize was that the worlds of branding and advertising already had a word for this sort of antagonism: “loss leader.” A loss leader is a product exchanged at a loss to attract customers for the future. From a certain perspective, this would include some of the most radical twentieth-century market-refusing art practices. Far from being an exception to the standards of established commerce, distributing free information that can be harnessed by an elite or restricted group with cultural legitimacy is the way conglomerates do business. Historically, artists have been regarded as forecasters of everything from style and behavior to speculative international futures. Trend reports are a vehicle for identifying emerging behaviors and the forces that motivate them. We issued our own because we wanted our community of peers to be aware of the strategies that were being used on them as consumers, and that they were parroting back in their own artistic and creative practices. Trend forecasting is a form of armchair sociology that identifies how consumers respond to global sociopolitical and environmental change through pattern recognition. Trends are less about seasonal colors, and more about consumers’ crisis response. Our thought was that the more people are aware of these strategies, the more they can develop tactics based on those strategies and use them towards their own ends, whether in their studio practice or in their plan for survival on Earth. For me, our practice was about peeking behind the curtain, gaining an understanding of the logic and intentions of corporate behavior, and seeing if there was any potential for us to affect change. We wanted to identify the threshold dividing viable from nonviable in the commercial sphere.

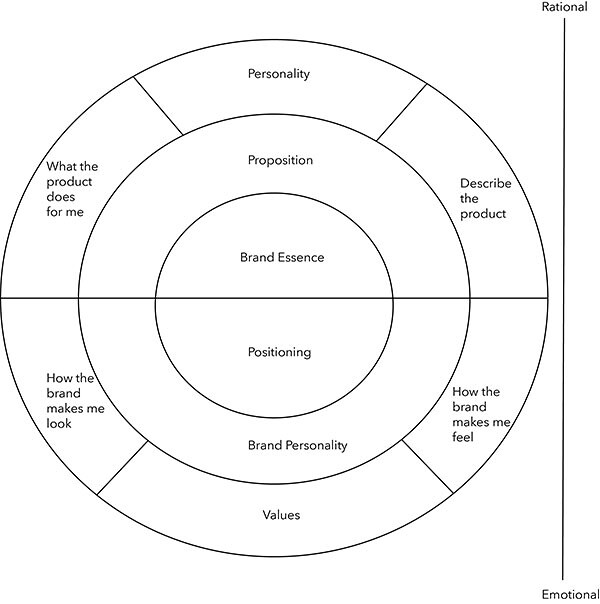

Our first two reports mirrored the traditional format, with the coining of a neologism, the definition of the trend, and the inclusion of supporting case studies. The first report was on “FragMOREtation,” a strategy by which brands play with fragmentation, dispersion, and visibility in order to conceal expansion and growth. The second was on “ProLASTination” and addressed the ways that brands seek ambient omnipresence over long periods of time. In 2012, after Hurricane Sandy and leading up to the Obama-Romney presidential election, we released K-HOLE #3, “The Brand Anxiety Matrix,” where you could plot brands, presidential candidates, countries, celebrities, and your friends, along two axes: from legibility to illegibility, and from chaos to order. We used anxiety as a metric to identify larger behavioral shifts. We crafted a collective voice that made hyperbolic declarative statements such as “The job of the advanced consumer is managing anxiety, period,” and “It used to be possible to be special—to sustain unique differences through time, relative to a certain sense of audience. But the Internet and globalization fucked this up for everyone.”

But as with all well-compensated prophecy, trend forecasting isn’t about seeing the future, not really; it’s about identifying collective anxieties about the future operating in the present. We dedicated our fourth report, “Youth Mode,” to generational branding. We described a crisis in individuality and a response to that crisis, which we saw as a rejection of the individual and an embrace of the collective, privileging communication and communities over individualist expression. We saw ourselves as living in Mass Indie times, with “Brooklyn” being arguably one of America’s largest cultural exports. The endless list of signifiers pointing to unique individuation leads to isolation, and when no one gets your references, you’re left alone and lonely. Instead of community building, the compulsion of individuation leads to “some Tower of Babel shit,” where “you’ve been working so hard at being precise that the micro-logic of your decisions is only apparent to an ever-narrowing circle of friends.”

We termed this approach “Normcore,” which resonated with people experiencing signifier overload and the pressure to be unique. Where our hypothesis was off was that this trend was less a response to fear of isolation and lack of community, and more about exhaustion. The dominant narrative around Normcore is understood in terms of normalcy and sameness, not communication and community. It was equated to dad jeans, Birkenstocks, and sneakers, and was runner-up for the Oxford English Dictionary’s word of the year. Our final report, released in 2015, was a report on doubt, magic, and the psychological trauma of collaboration.

After “Youth Mode,” we were approached by brands and agencies to speak at corporate conferences, hold workshops, and create custom research reports. Asked about our methodology, our answer was something like “we just hang out a lot.” In our workshops and brand audits, we told brands what they were doing wrong at a meta-institutional level. We were not brought in to provide tactics, just strategy. Or rather, we were the tactics: we were invited into the room so that strategists, creative directors, and work-for-hire creative agencies could signify to their C-suite executives and clients that the brand was engaging in radical strategery. They brought us in to provide cultural credibility, not to actually implement our work. MTV asked us to write a manifesto to inspire their employees about the brand. We delivered a “manifesto” that included what we imagined were harmlesss platitudes like “Breed unique hybrids,” and “If we’re for everyone, we’re not for anyone.” Even so, the most pointed suggestions in the document were edited to make it acceptable for upper management. Our demand for the cancellation of the Real World, for example, became a gentle suggestion that MTV “have the courage to put things to pasture.”

The World Economic Forum sent a representative in a grey pantsuit to our fifth-floor Chinatown studio to invite only one of us to Dubai for the organization’s “Global Agenda Council on the Future of Consumer Industries.” We were told, in a tone of forced casualness, that entire phalanxes of corporate executives met at such councils to set an agenda for the coming year. A few years prior, the agenda had been entitled “Sustainability and Mindfulness.” It was unclear what came of these terms, or what the exercise accomplished aside from fostering a sense of corporate responsibility and dedication to the “double bottom line.” These were bloated, entrenched monopolies gathering in a gilded desert to confirm to themselves that they had not totally lost their taste for truth. Hired to provide such vérité, our role was like that of a royal soothsayer, and gigs became a productive exercise in failure. We quickly learned what kind of work we had to do in order to “pass”—that is, to be seen as the thing itself rather than as art-school imposters. While we offered strategy and insights, any tactics or ideas for execution that we brought to the table stayed there. Corporate clients can’t stand to feel like they’re being trolled. To many clients, we were useless beyond our cultural capital or “brand equity.”

It became clear that what constituted trend forecasting “in itself” in the case of K-HOLE was the collective work of immaterial, unlocatable, affective, and knowledge labor. That, and the effusive, intangible, shape-shifting, and value-adding fog of branding. We realized that behind the multinational curtain is a decentralized quagmire where no one is held accountable and decisions are driven by fear. Corporations are people, US presidential candidate Mitt Romney said, and people need jobs, and jobs are jeopardized for all sorts of dumb, cyclical reasons without adding reckless departures from precedent. This is why, increasingly, most successful entrepreneurs—like most successful artists—come from some kind of money. Genuine risk-taking is usually the mark of desperation, mental illness, or both. We were brought in as crisis control, for brands and agencies to prove both internally and externally that they were self-aware and not ready to die.

We were court jesters, hired to tell creative directors and executives about their follies. They were the masochistic kings paying to hear how their messy and often violent business of accumulation disgusted us. But, like the dominatrix or jester, we were still contract workers. Power likes to hear truth spoken in its presence rather than whispered in the shadows, as a substitute for seeing it acted upon by others. In our final report—K-HOLE #5, “A Report on Doubt”—we conceded that seeing the future ≠ changing it. Networks of power and influence remain the same. To quote Sun Tzu in The Art of War: “Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.” It was worse than I could have imagined.

For the past two years I have worked as a trends and strategy consultant for various creative agencies and media companies, and as a strategist for an advertising agency in Los Angeles. The LA agency’s two primary offices are open plan and dog friendly. Like service animals, the office dogs are there to absorb the emotional trauma that their owners experience while they hash out content calendars and campaign strategies. These are positions that deal in pure affect, and I have become intimately familiar with the language through which corporations narrativize and justify their position and actions. It is a corporate logic that speaks in sweeping generalizations, thus erasing difference and constructing statements on human universal truths with ulterior motives. At no point in this work have I felt like I’m engaging in détournement. Any attempts to translate critique into tactics have been exercises in futility. I suggested that a light-beer brand address its role in rape culture and create a campaign supporting the implementation of Title IX on college campuses. I recommended that a bank divest from the Dakota Access Pipeline as a campaign strategy. I developed a strategy for a television show that dealt directly with issues of reproductive rights and used the show’s platform to direct attention and resources to groups like Planned Parenthood and the Center for Reproductive Rights. Needless to say, these efforts did not result in bank divestments or brand-sponsored resources for victims of sexual assault. The television show opted for artist collaborations and a fashion capsule collection. I’ve witnessed how brands privilege the unquantifiable asset of cultural relevance precisely because of its slipperiness. It does not have to function to work.

My inability as an artist or simply an individual to effect change within corporate structures has not resulted in a radical turn towards art, or an essentialization of my identity as an “artist.” Rather, I have been producing and exhibiting art and poetry concurrently with these experiences. While the economy of language and image and the specific language I’ve encountered permeate my writing, I do not directly make work “about” branding. The office is not a site of artistic production for me, and in this sense I am not wearing Certeau’s wig as a diversionary tactic. The erasure of complexity in both thought and representation that I witness in my hired work has made me more idealistic about art as a space with the potential to embrace complexity, and to counter the on-demand speed mandated by our culture at large. It has allowed me to distinguish the making of art and a community of artists from the art market.

Art As UGC

Artists have traditionally included brands, logos, and readymade consumer goods into their work in order to mount critique on consumption, globalization, mass production, and art-as-commodity. Now you have works created with contemporary brands and products, be it Axe, Monster Energy, Doritos, Red Bull, images of which are then posted and shared on social media. On the other end, you have a social media manager with a liberal arts degree scanning hashtags and coming across their brands being worn and consumed by artists and appearing in the artworks themselves.

Of-the-moment consumerism rewards a level of complexity that answers the question “why not have it all?” You can like both Dimes and Doritos, sincerely and without irony. The mixing of “high and low” points both to self-awareness and being in the know. Lux T-shirts with licensed DSL logos, fashion presentations taking place in White Castle, Pop Rocks on your dessert at Mission Chinese.2 This sincerity has taken precedence over critique or resistance. Somewhere along the line it became acceptable to be authentic, earnest, honest, and sincere, even if the object of this sincerity is a complete celebration of consumerism. The primacy of affect over rational thought has, in large part, led us to our current state of political affairs far beyond the realm of art. Subjective emotional truths are being taken as objective rationality-driven realities. With alternative facts, truth is malleable, and as we see with crime footage posted to social media, forensic visual evidence has not resulted in structural change.

Instead, in the realm of art and creativity, when posted on social media these brand and consumer good laden images function as user-generated content (UGC), authentic marketing material being promoted by the coveted creative class. Art that incorporates brands and readymade branded products has become earned media. Earned media is free advertising; it’s what news outlets provided for Trump, which would have otherwise been regulated and campaign financed. Paid media is publicity gained through paid advertising, while owned media refers to branded platforms, websites, social media accounts.

This brand inclusive art is user generated content. It is not even sponsored content, in which the artist would be paid for posting images of the brand to social media, or paid to incorporate the brand into the artwork itself. Any critique is sublimated, and the artist, like Leslie in season 19 of South Park, doesn’t even know she’s an ad.

Taking on the role of Patron of the Arts, Red Bull Studios provides resources and physical space for artists and musicians to create and exhibit their work. They are facilitating the creation of work that an artist may otherwise lack resources for, but that work must now be understood as sponsored content. While artists and musicians stage exhibitions in Red Bull branded spaces, the brand’s CEO, Dietrich Mateschitz is launching his own Breitbartian conservative new media platform, Näher an die Wahrheit, or “Closer to the Truth.” While there are artists exploring the potential of this role as content creator, and artwork as sponsored or user generated content, this is not something I would like to explore in my own practice. There is no critique, no position of power for the artist in this exchange. We must shift our understanding of this form of work and acknowledge the way that it is being instrumentalized by brands on the other side of the feed. Having influential creatives touting the brand’s products on social media and in the work itself is their goal.

Artists who participate in this might feel that their radicality lies in goes against a culture of liberal critique, that they are being “anti” by embracing the commercial. But it becomes a question of scale, of knowing one’s own insignificance and finding a form of resistance that doesn’t start to feel like reactionary consumerism. One form of resistance is to go dark, to stop making artwork that can in any way be represented on the platforms that facilitate these forms of recuperation. But even if you as an artist don’t post images of your work on social media, other people might. You could institute a Berghain rule and administer stickers over phone’s camera lenses upon entering an exhibition, but then, hashtags are indexable forms of language that don’t require images and are still a useful metric for brands. You could literally never show your work to anyone. You could embrace chaos and illegibility, creating visual or written work that is non-instrumentalizable, but legible across many parts over a longer period of time. This might mean making work that operates at a different tempo than that of branding and social media, work that occupies multiple sites and forms, work that fights for the complexity of identity (as artist or otherwise) and form, and believes in a creaturely capacity for patience with a maximum dedication to understanding.

Hal Foster, The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 198.

Dimes and Mission Chinese Food are fashionable eateries on the Lower East Side, New York.

All images unless otherwise noted are courtesy of the author.