In March 1977, Koorosh Shishegaran created ART+ART, a poster he mailed to several recipients including major newspapers in Tehran. The bilingual poster asserts that “K. Shishegaran’s works” are “Shahreza Ave. itself.” The design consists of a thick black line, reminiscent of a road but winding in swirls and tangles, marked as “Shahreza Ave.”; the bilingual text on both sides of the spiral says that Shahreza Ave. “is painting,” “sculpture,” and “architecture,” as well as various other artistic media, including writing and dance. The public’s reaction was one of confusion and, at times, hostile dismissal. In response, Shishegaran wrote replies to the newspapers to clarify his intention: “Some people think that I am showing my works in Shahreza Ave.,” he wrote, “but I am, in fact, introducing the street itself, the people in the street and the good and bad that happens there, as a work of art.”1

Koorosh Shishegaran, ART+ART ,1977. Silk screen print on paper, 80 x 60 cm.

Compositionally and aesthetically, Shishegaran’s design was unusually minimalist. While other Iranian designers of the time commonly demonstrated their artistic authorship through their palettes—their use of original illustrations and creative combinations of type and image—Shishegaran’s work consisted of plain colors, conventional fonts, and a deductive structure dictated by the limits of the rectangular frame, internally divided into further symmetrical rectangular sections.2 The drawing in the middle, presumably indicating the movement of a viewer along Shahreza Avenue and connecting the two edges of the frame, eliminates any element of handicraft and conveys a mechanical mode of image-making. The intertwined movement of the spiral and the smooth changes in its thickness convey a sense of dynamism, yet this animation is curbed by the text’s matter-of-fact mode of interpellation and by the jaded symmetry of the overall composition. Shishegaran clearly distanced himself from the “expressive” approach of most other Iranian designers. However, it was less his critical engagement with conventions of graphic design than his radical negation of art as such that made ART+ART striking. By inviting people to see an art exhibition which was nothing more than the street through which many of them passed on a regular basis, Shishegaran launched a campaign against institutionalized modernism, which had been flourishing in Iran for almost two decades. As such, the poster’s reduction of the author’s function reflected multiple textual iterations in the body of the work: that is, that the real artwork is Shahreza Avenue.

In order to assume such a subversive position, ART+ART situates itself somewhere on the borderline of institutional modernism, both within and without it. This is partly negotiated through Shishegaran’s choice of the medium of poster design, which has a peculiar trajectory in the history of Iranian modernism.

In Iran, exhibitions are often advertised with posters by designers whose work is held in equally high regard, to the extent that some galleries occasionally hold exhibitions dedicated to such posters. These announcements are therefore an integral part of the institution of art but have always remained separate from the art itself, which was considered beyond such institutional dependencies. The posters were a part of the exhibition that was not recognized as being constitutive of it. By reducing the materiality of his work to one such poster, Shishegaran occupies a position which is immanent to the institution of art, yet he subverts this position by using it to declare art to be elsewhere.

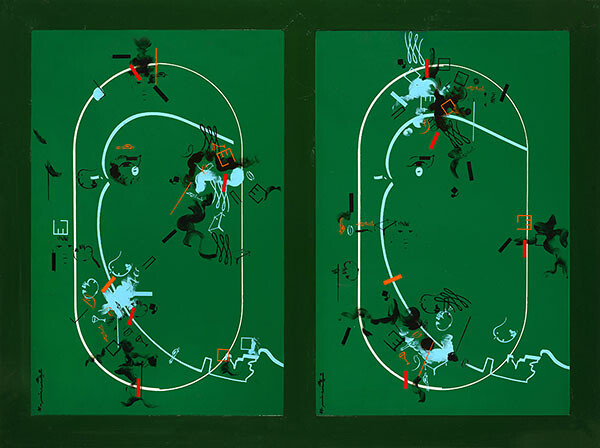

ART+ART itself did not come out of nowhere. Since the beginning of his artistic career, Shishegaran, who was born in 1944 and studied interior design at Tehran University of Art, had sought to break through what he called “the hard shell surrounding our understanding of art.” His main concern was that “art is treated separately from society” and that “obstacles are placed between people and art.”3 Shishegaran envisaged artworks that could be reproduced or even transmitted on radio and television. His first solo exhibition, in 1973, consisted of a series of paintings (single and diptych) made using car paint on wood panel. Each work was dominated by its distinctive, flat background color; in their foreground, Shishegaran arranged alternating compositions using a pool of shared elements, including everyday objects such as tables, chairs, glasses, birds, cars, and fruit. These elements were schematically drawn with simple lines, juxtaposed with casual abstract motifs, and organized around a unifying oval or rectangular form that dominated the composition. Seen together, the series appeared as as collection of dispassionate studies on a single theme, whose mechanical nature was emphasized through the artist’s reference to industrial production (particularly car paint and identical, serial framing), as well as his employment of the logic of architectural floor plans (each work seemed to be an arrangement of objects on a floor plan, while little details of drawing reproduced the conventional lexicon of floor-plan drawings). Out of the fifty works presented in the show at Mes Gallery, thirty were given away for free to be exhibited in places accessible to the public, from the University of Tehran to a regular high-street shop. The artist was happy for the works to have a reproducible grammar, to the extent that a few months later he made another exhibition of “the second execution” of these works. He termed them “reproductive art” and asserted that their aim was “to grant social power to the work and to open the way for the artwork to get out and into society at large.”4 This practice was inspired by Shishegaran’s education in interior design, but it also took cinema as its model. According to Shishegaran, “For painting, like cinema, we must have a producer/investor” so that “the work does not end up only in one person’s hands.”5 Taking Shishegaran’s logic one step further would mean that the condition for painting’s sustained social relevance would be for painting to give in to print.6

Koorosh Shishegaran, Bird, 1973. From the “Reproduction Art” series, car paint on panel, diptych, 94 x 127 cm.

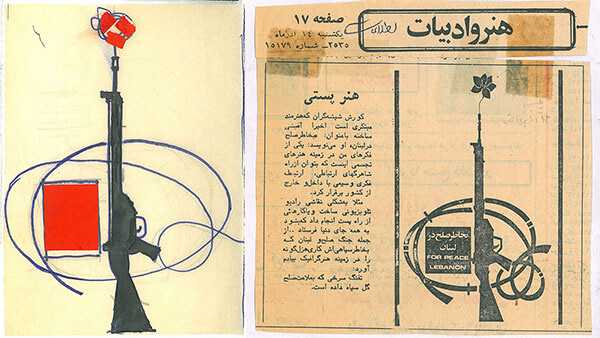

This is the position Shishegaran arrived at in 1976. He made a simple postcard entitled For Peace in Lebanon and mailed copies to various newspapers and magazines, independent artists and intellectuals, as well as people on the gallery’s mailing list. The back explained that the card was “Postal Art” by Koorosh Shishegaran, and that it had a “producer.” It also announced a gallery presentation taking place in November at Iran Gallery (later known as Ghandriz Gallery). It was in this work that Shishegaran, for the first time, turned to graphic design, further distancing himself from the tradition of painting; the decision to erase the artist’s hand from the final work seems to have been deliberate. As Shishegaran’s sketches for this work show, he specifically moved towards a formulaic arrangement of elements, with final images appearing schematic, simplified, and machine-made. In “Postal Art” Shishegaran took the critically pressing question of art’s social relevance to another level. If, in “Reproductive Art,” painting is dissolved into industrial and mechanical modes of (re)production to maintain its social relevance, in “Postal Art” the artist forgoes the idea of painting altogether, yet maintains an ambiguously expanded notion of “art”—one that includes neologisms such as “postal art”—with the hope that the form of the work will reflect its socially urgent subject matter, that is, peace in Lebanon. It is in this context that Shishegaran’s next major work, ART+ART (1977), emerges as the radicalization of the artist’s own practice. In his attempt to bridge the gap between art and society, the two entities become one; all that is left for art is to simply announce this unification—“K. Shishegaran’s works: Shahreza Ave. itself.” Nonetheless, there was another aspect to Shishegaran’s provocative gesture. Since the beginning of his career, he had been engaged in a critical dialogue with the Iranian art scene. What Shishegaran identified as the gap between art and society was not so much his own discovery as a predicament in which generations of visual artists in Iran had hitherto been trapped. ART+ART can be best seen as a radical response to this tired debate; as such, it directs us to revisit the history of Iranian modernism in light of this declaration.

From its inception in the late 1940s, Iranian modernism constantly found itself facing an indifferent public that considered modern art socially irrelevant. In retrospect, the history of modernism in Iran looks like a history of artistic attempts to overcome this sense of alienation from the public. But the more art tried to bridge the gap, the deeper the gap between art and the public grew. In this context, ART+ART came less as a new response than as a radical negation of the presuppositions of the question itself. Shishegaran’s work turned the question of the art-public relationship on its head and dissolved the binary between art and life altogether. To understand the significance of this gesture we must discuss Iranian modernism further.

Left: Koorosh Shishegaran, sketches for Postal Art: For Peace in Lebanon (1976). Right: Postal Art: For Peace in Lebanon as it appeared in the Ettela’at newspaper, December 5, 1976.

Iranian Modernism: Provincial Liberation from the Academy

Social relevance was a constitutive question in Iranian modernism. The first artists who advocated modernism articulated their position primarily as an attack on academicism’s social irrelevance. They introduced modernism as the language of the day, while holding academicism’s inadequacy responsible for people’s indifference to art. As early as 1948, when Jalil Ziapour (1920–99), one of the first Iranian graduates of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, returned to Tehran, he joined forces with three others—a musician, a novelist, and a playwright—to form a collective called the Fighting Cock. His intention to champion cubism as “the most recent and most successful” development of art in Europe was slightly out of key—in Europe and many other places cubism was already considered an accomplished mission of the past. Nevertheless, Ziapour’s intervention considered a shift in the ontological concept of painting from academicism to modernism. His call to arms, a four-part essay published in the collective’s journal, placed the blame for the public’s disengagement with art on an outdated academy. “Our artists often complain that our society is not welcoming to artists and people do not understand art,” Ziapour asserted,

but they fail to realize that … most of our artists, young and old, only create portraits of dead kings or landscapes around Tehran, yet—just because their so-called naturalist paintings demonstrate technical proficiency—they expect people to appreciate them, while in fact, they are copycat imitators of hackneyed conventions from previous centuries.7

Ziapour claimed that unless Iranian artists embraced modernism, art would not become relevant to their society. However, modernism could not fully solve this presumed split between art and the public, because it was often seen as alien to the lived culture of Iranian people. Because modernism had been codified in Paris before being exported elsewhere, it always carried implications of cultural imperialism. As the art historian Terry Smith has put it, outside Western Europe, modernism has always been characterized by “an attitude of subservience to an externally imposed hierarchy of cultural values.”8 Ziapour himself demonstrated a similar attitude when he went on to say,

When a person with good taste enters the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris and encounters the magnitude of conflicts between divergent schools of painting, this experience is so unsettling that it raises various questions … These questions are so powerful that in themselves they can make a curious mind understand the real meaning of art and painting. We should confess that our painters are centuries apart from the real meaning of art.9

Nonetheless, despite modernism’s European derivation, for Ziapour and his cohort it amounted to a universal language. In his paintings, Ziapour adopted Cubist innovations to create an art that was more or less his own; this put him in the first generation of artists opening a route that would define Iranian modernism for years to come. Ziapour’s adaptation of the language of modernism was perhaps a sign of confidence rather than subservience, because he and those who followed him saw themselves as being in a position to ignore modernism’s historical construction and claim it as their own, in an act of appropriation. In reality, however, considering modernism as a universal form resulted in a binary opposition between the presumed universality of modernism as a language and a search for particular, locally specific content with which to fill that form. This binary, which would haunt Iranian modernism for many years, was exactly what Smith termed “provincialism.” According to Smith, provincialism was not simply a result of peripheries imitating the center; rather, modernists from outside the international centers were constantly pulled between

two antithetical terms: a defiant urge for localism (a claim for the possibility and validity of “making good, original art right here”) and a reluctant recognition that the generative innovations in art, and the criteria for standards of “quality,” “originality,” “interest,” “forcefulness,” etc., are determined externally.10

In the context of Iran, this double bind helped create a new national style of modernism, but it also internalized some structural problems of colonialism within the local context.

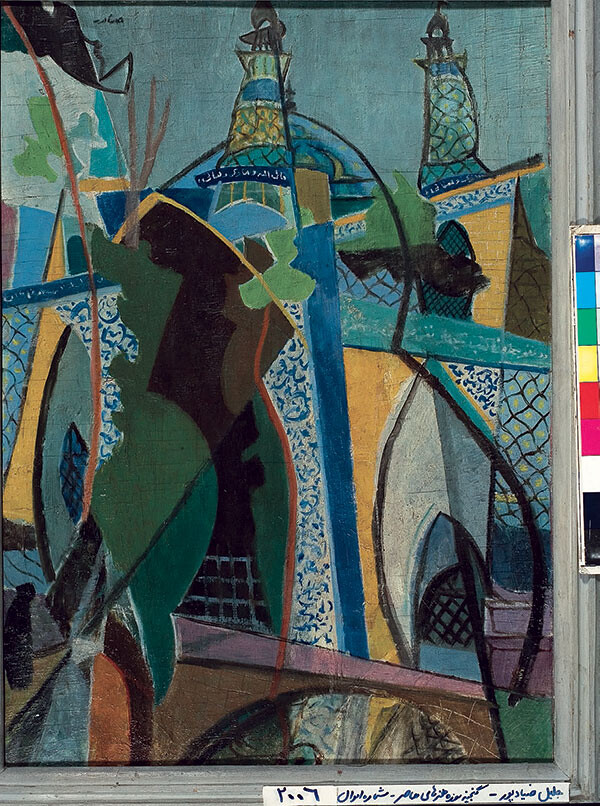

Jalil Ziapour, Kaboud Mosque, late 1940s. Oil on canvas. Collection of Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

Modernism, Identity Politics, and Administration of the Public Space

The second defining moment in the history of Iranian modernism came in the early 1960s, with the emergence of a group of young artists who valorized the binary divide between the universal language of modernism and the particularity of their own situation. These artists gained recognition for exploring a “modernism with local content,” appropriating and incorporating Persian painting and calligraphy and traditional craft motifs into the media of easel paint and bronze sculpture, resulting in iconographically Iranian yet formally modern artworks. Hossein Zenderoudi, a paragon of such work, incorporated traditional practices of siahmashgh and talisman-making into his painting. Siamashgh is a working method in which artists write quite indiscriminately across any and all parts of their paper in order to practice their technique, without any concern for the overall composition. Zenderoudi took up this all-over aesthetic but organized it according to the edges of a canvas, producing extremely sophisticated but essentially unified compositions and thereby mediating between a traditional Iranian practice and Western easel painting. Another classic example would be Parviz Tanavoli’s cage-like sculptures, created by combining the form of the mausoleums found in most Iranian neighborhoods with his own versions of objects that he saw in old-fashioned markets—locks, tools, etc.—which viewers would have associated with old-fashioned crafts and an eternal sense of Iranian-ness. Ultimately, what the viewers found in these works was a mixture of Islamic and pre-Islamic images, all linked to a sense of national identity. However, their compositions were mostly adapted from European examples, albeit in a particular and idiosyncratic way. This new approach in modernism was soon given a name—Saqqakhaneh, after the traditional art of water-fountain making—and its artists received considerable support from the government.

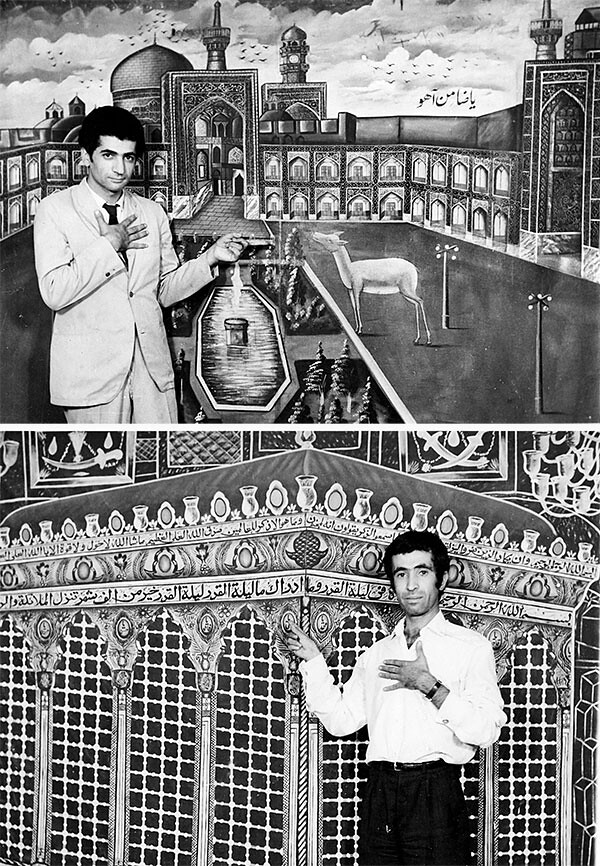

Artists Parviz Tanavoli (top) and Hossein Zendehroodi (bottom) pose in front of a painting in a photographer’s studio in the religious city of Mashhad, were Imam Reza’s Shrine is located (1965). Photographs like these were a standard memento from a kind of pilgrimage that was most popular amongst the lower classes. Images from the memoirs of Parviz Tanavoli, Kabood Atelier.

The two champions of Saqqakhaneh, Tanavoli and Zenderoudi, came up with their idea after a trip to the working-class neighborhoods of southern Tehran. Art critic Karim Emami’s account of that trip in a lecture in the early 1960s signifies a critical moment in the relationship between modern art and the public in Iran, and is therefore worth quoting at length:

Tanavoli recalled how one day he and Zenderoudi had together made a trip to Shahr Rey, and there had been struck by the Moslem posters displayed for sale. They had both been looking for local materials that they could use and develop in their work, and these posters appeared like a godsend to them, he said.

The copies they bought and took home fascinated them with their simplicity of form, use of repeated motifs and bright, almost gaudy colors. The first sketches that Zenderoudi made on the basis of these posters, Tanavoli said, constitute the earliest Saqqakhaneh works.11

With Saqqakhaneh it seemed that the nation had finally managed to bridge the colonial gap and invent its own modernism. By adopting elements borrowed from working-class neighborhoods and transforming them into works of modern art, the new art seemed to have managed to combine the “Iranian,” the “common,” and the “modern.” According to Shiva Balaghi, the work of Saqqakhaneh artists demonstrated a resistance against colonial modernity, by manifesting “at once a mode of appropriation and of resistance.”12 However, what Balaghi fails to discuss is the genealogy and geopolitical constitution of the notion of Iranian-ness upon which the Saqqakhaneh school was based. In the context of the early 1960s, authentic Iranian identity was an ideological cornerstone of the Pahlavi government and, despite its anticolonial appearance, was deeply rooted in the conceptions of Iranian-ness articulated in the work of Western Orientalists.13

Saqqakhaneh artists were first exposed to the ideology of “Iranian authenticity” through art schools. As the art historian Hamid Keshmirshekan has noted, “one of the common characteristics of most members of the [Saqqakhaneh] group was that they had studied at the Tehran Hunarkadeh-i hunar-hay-i taz’ini,” or School of Decorative Arts.14 Hunarkadeh, which opened in Tehran in 1961, was established by the first generation of Iranian modernists to counter the dominance of academism in the educational field. Its curriculum, however, was not simply adapted from European schools; it also incorporated courses on the history of Iranian philosophy and Iranian design.

Interestingly, this shift towards Iranian history was influenced by the ideas of two giant Orientalists of the time, philosopher Henry Corbin and art historian Arthur Upham Pope. According to Pope, Persian art, from prehistoric times to the present, has been consistently concerned with the “decorative” as the site of “pure form.”15 Influenced by Pope’s understanding of Iranian art, students at Hunarkadeh were encouraged to investigate the “decorative” qualities of traditional art—whether in “elite” historical artifacts or in the “primitive” common culture—and incorporate these qualities in their modernist works.16 Moreover, the Hunarkadeh curriculum reflected a philosophical narrative of Iranian identity that Henry Corbin had articulated.17

While the Pahlavi government strived for an eternal narrative of Iranian identity, Pope and Corbin offered metahistorical visions of Islam which granted Pahlavi’s secular and military outlook a spiritual dimension. It is therefore not surprising that the Iranian government enthusiastically supported Saqqakhaneh artists; the director of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art at the time referred to the movement as “a spiritual Iranian version of Pop Art because it involved the nonmaterial consumption of traditional Iranian mass culture—like folk art or talismans.”18

Inasmuch as Saqqakhaneh derived from an ideologically conservative understanding of local identity, the work made by its artists also reflected and reproduced Orientalist tropes rather than resisting them, despite the artists’ insistent locality.19 In 1966, the charismatic public intellectual Jalal Al-e Ahmad (1923–69) charged that the emerging taste was being constructed for the Western gaze. The problem, for Al-e Ahmad, was that the appropriation of calligraphy and traditional talismans served to remystify popular culture, whereas, he argued, “the task of the artist is to unravel the relationship between people and things and to demystify their spell.”20 Although Al-e Ahmad did not offer any detailed formal analysis of these works, for him, decontextualizing local elements and treating them as purely aesthetic motifs was reminiscent of colonial arrogance. After all, Saqqakhaneh involved expropriating themes originating in working-class and popular culture and turning them into highly unified, monumental, elite works of art, primarily executed in the noble media of oil paint and bronze sculpture and shown in the gallery spaces of Tehran’s affluent neighborhoods, particularly the art gallery at Iran-America Society.

The geopolitics of this national modernism can be mapped onto the distribution of wealth in the city. It entailed a movement from the downtrodden south (Shahr Rey), where the raw material and sources of inspiration lay, to artists’ studios and galleries in the north. Although Saqqakhaneh brought the public into the space of art, the works themselves covered up the class divisions that were constitutive of both the public and Saqqakhaneh—the divisions between the north and the south, and between the middle-class artist and the working-class craftsman. These slick artworks reproduced the nation at the level of an image, but one devoid of the historical and material tensions of the “real” nation out there. In that sense, Saqqakhaneh was complicit in the Shah’s ideology of “official nationalism,” itself based on a naturalized and ahistorical notion of “authentic” Iranian identity. It is therefore not surprising that Saqqakhaneh failed to overcome the public’s age-old alienation from modern art.

Attempts to reconcile the public with art were not limited to creating images of reconciliation. There were also artists who actively engaged with the city. In 1964 a collective of painters, sculptors, graphic designers, and architects established a gallery in central Tehran, opposite the main university campus on Shahreza Avenue. Ghandriz Gallery (inaugurated as Iran Gallery) opened new pathways in addressing the public’s alienation from art. First, it was an artist-run space, class-neutral in appearance, with most of its members coming from humble backgrounds. Although the gallery received a small monthly subsidy from the government to help pay the rent, it was more or less economically independent. More importantly, the gallery experimented with new and more engaging approaches to art. Over the next fourteen years, it dedicated its central location not only to showing the works of younger artists with no other platform, many of whom would become defining figures in the coming years; it also vigorously explored potential continuities between modernism and nineteenth-century Iranian art. Apart from solo and group shows of new works by Iranian artists, popular exhibitions at Ghandriz included record sleeves, nineteenth-century Persian prints, reproductions of works by European masters, and exhibitions of Iranian and international poster design. These exhibitions were commonly accompanied by low-cost educational publications. According to Ruin Pakbaz, a prominent member of the collective,

The viewers expected the artist to explain their work and clarify its ambiguities. That was a reasonable request, because there was a huge gap between the artists’ personal experiences in the realm of modern art and the viewers hackneyed conception of visual arts … As well as exhibiting artworks, we had to improve general knowledge and understanding of art.21

At Ghandriz Gallery, the gap between modernism and the public was translated into a gap between the advanced artist and the uncultivated viewer. The question of modernism’s social relevance was thus transformed from a question of aesthetics (the artistic style and appearance of the work) and economics (class) into a question of culture. Culturalizing the crisis of art resulted in an even deeper gap between the public and modern art. With its attempt to educate the public up to a supposedly “appropriate” cultural level, the Ghandriz collective in fact reproduced the binary and ended up engaged in a vain attempt to make the public interested experts in autonomous modern art—while autonomous art, by definition, kept changing.

After fourteen years, the collective gradually became disillusioned about the prospect of reconciliation. It is therefore not surprising that as soon as the revolution started in 1978 and people took to the streets, the collective decided to close down the gallery and leave the public space of the city to the people. Politics had rendered the cultural question redundant.

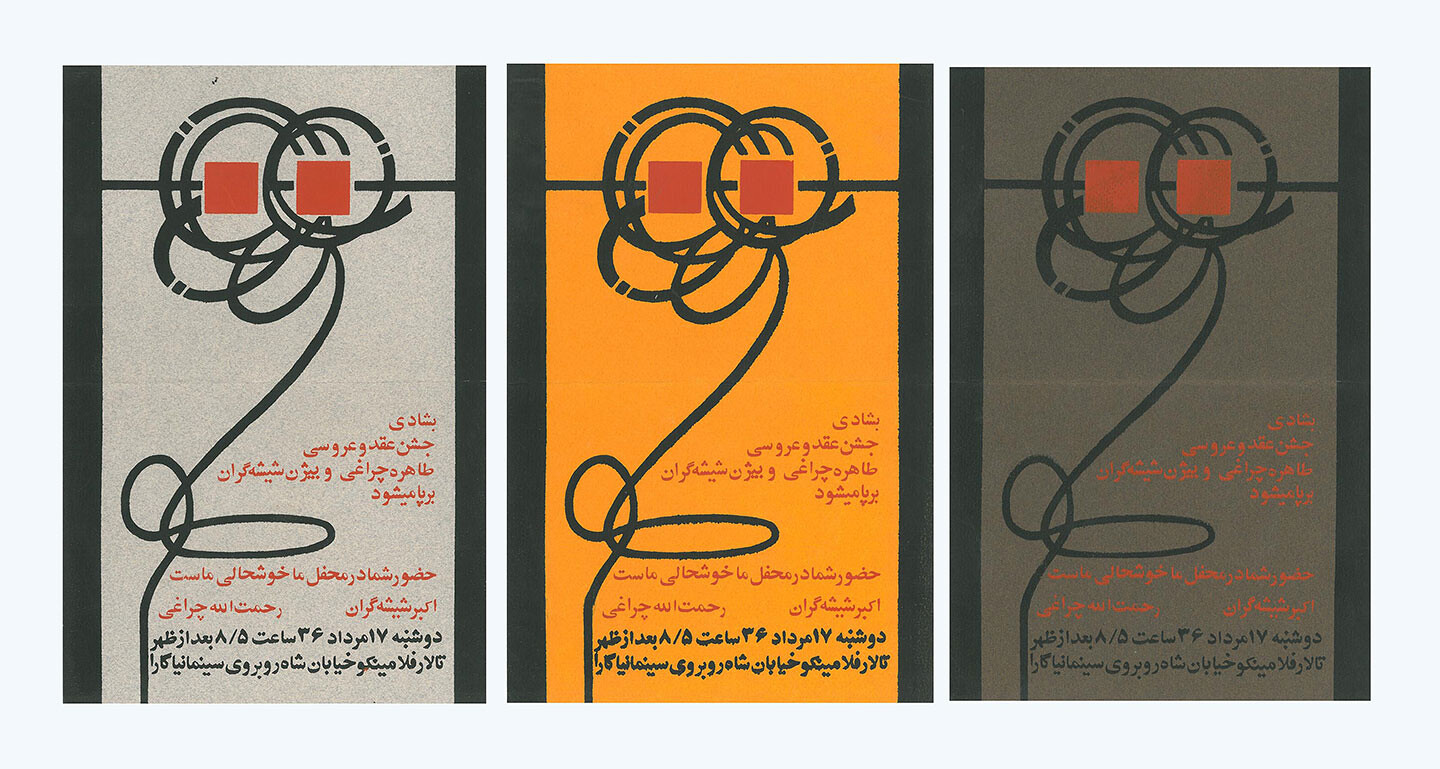

Koorosh Shishegaran, Tahereh Cheraghi and Bijan Shishegaran Wedding Card (1977).

Modern Art and Common Space: Reform and Revolution

It is important to see Shishegaran’s ART+ART in the context of these institutional debates around modernism’s social relevance. His work offered a radical alternative to the common practices of autonomy. He tried neither to bring elements of street life into the gallery space (Saqqakhaneh) nor to take his art into the street (Ghandriz). Instead he declared the dissolution of art and street into one another: “Kourosh Shishegaran’s works: Shahreza Ave. itself.” This was a strong self-criticism of the art scene—a criticism that radically negated the abiding preoccupations of that art regarding the disengagement of art and life. According to Shishegaran, the street itself is already art. Shahreza Avenue is painting, Shahreza Avenue is sculpture, Shahreza Avenue is architecture, Shahreza Avenue is graphic design, Shahreza Avenue is cinema, Shahreza Avenue is theater, etc.

In his Theory of the Avant-Garde, Peter Burger famously argues that “the avant-gardistes proposed the sublation of art—sublation in the Hegelian sense of the term: art was not to be simply destroyed, but transferred to the praxis of life where it would be preserved, albeit in a changed form.”22 A reintegration of art into the praxis of life is exactly what Shishegaran pursued. He asked people to take to the street and consider the bustling Shahreza Avenue as a work by Kourosh Shishegaran. “A street, or a slice of our lived life,” Shishegaran wrote in response to a critic, “is a monumental and extraordinary work of art that encapsulates all known arts. Maybe I could have called this poster Living Art.”23

But there is more to Shishegaran’s attempted sublation of art than mere admiration of urban life. By specifically choosing Shahreza Avenue in particular as the site of “life,” Shishegaran reintroduced political economy into an otherwise culturalized domain. Ghandriz Gallery was also located in Shahreza Avenue. For the collective, Shahreza Avenue represented a generic public space, a geographically central street that marked the south-north divide but was also home to the university campus and major bookshops that attracted the intelligentsia. As liberal modernists who envisaged crossing the gap between art and the people by making their art available to a generic, class-blind conception of the public, the collective found Shahreza Avenue a perfect location for their gallery space. At the same time, Saqqakhaneh artists were only interested in the two opposing ends of the class gap: the working-class south and the bourgeois north. They did not mind exhibiting in Shahreza Avenue, but rarely looked for inspiration there. For their kind of class consciousness, Shahreza Avenue was too ambiguous: instead of representing any clear class character, it was the crossing point between opposing groups and thus impossible to pin down. More importantly, Saqqakhaneh artists were stylistically prone to naturalizing the class gap and creating aesthetically unified objects as undistinguishable syntheses between plebeian motifs and patrician media. Shahreza Avenue did not allow such aesthetic normalization because it was precisely the site in which different classes exhibited their differences. In Shishegaran’s avant-garde work, these class antagonisms take center stage and become not only the subject of art but the site of its dissolution.

The compositional symmetry of Shishegaran’s poster along both the horizontal and the vertical divides, facilitated by the bilingualism of the text, mirrors the doubling of the title, ART+ART. It also indicates the difficulty of a resolved sublation and of transferring art into the praxis of life. Art and life are added together, but that arithmetic somehow returns a non-unity of the two halves, as if any possibility of sublation had to be mediated through a reconciliation of class antagonisms. That is in some ways what the work also points towards. ART+ART is a call to take to the street—a particular street where these antagonisms are best demonstrated. Therefore, it is equally a call for class revolution. One year after Shishegaran created this poster, a revolution stormed through Iran and toppled the old class structure. The fact that this revolution was mainly staged in Shahreza Avenue gives the work an uncanny prophetic quality. Shahreza Avenue was soon renamed Enghelab (Revolution) Street.

Nothing can demonstrate the sense of anxiety that Shishegaran’s work caused amongst its audience better than a story published in the Rastakhiz daily newspaper in response to the work. The writer sets out on a journey to Shahreza Avenue to prove to his readers that it is absurd to claim that this street is in any sense a work of art. At times he uses strongly pejorative language, but in retrospect his prose becomes unintentionally funny because, in its attempted dismissal of the work, it reveals the work’s startlingly avant-garde quality—the modern urban space aggressively crashing into the supposed tranquillity of autonomous art.

Fouzieh Sq. In the long shot, half of the population of all provinces have flocked into the square. Medium shot, a bloke punches a poor guy in the guts (on the soundtrack, the guy moans). Close up, the poor guy’s broken tooth a few meters away. Camera zooms in on a poster, “Shahreza Ave. is cinema,” the text reads, “is theatre, is poetry … is art plus art.” The loud sound of a car horn mixed with the excited commotion of passengers on a double decker bus cuts off this cinematic and theatrical scene.

There is an abandoned gas station (probably a modern sculpture?) which was closed down by the union because the owner mixed the gas with cheap diesel. Was it closed down because it compromised the artwork? After all, this place is art + art, not gas + diesel or any other arbitrary sum or subtraction. Now that the gas station is closed, the art’s purity and authenticity are restored.24

With Shishegaran’s ART+ART, Iranian modernism finally acquires a belated avant-garde. As such, one can argue that a national modernism hitherto unable to internally address its own contradictions finally became, in a dialectical way, responsible for its own shortcomings—that is, a critique from within. ART+ART can thus be considered an act of institutional critique, so to speak. However, Shishegaran has always insisted that his main concern was not simply to criticize other people’s art so much as to achieve a state of pure art, independent from social conventions of art-making. When a critic claimed that ART+ART was a second-hand artwork because it was similar to works previously produced in the West—“for example, a long time ago Ad Reinhardt chose and presented a piece of gallery wall as ‘a space chosen by the artist’ and even sold that unmovable piece”25—Shishegaran responded by emphasising his attack on Iranian modernism. He said,

If someone manages to rip off the hard shell that periodically forms around the “work of art,” if they manage to open up new horizons, even minimally, their work has a much higher quality than the work of those who simply repeat traditional conventions and stay within the hard shell, no matter how good they at repeating those conventions.26

At first glance it might seem as if Shishegaran intended to replace autonomous modernism with a more committed and socially engaged art. However, as this statement suggests, he was primarily interested in critiquing a “traditionalism” disguised as modernism: that is, the uncritical reproduction of certain predefined conventions by artists who thought of themselves as independent modernist artists. In other words, Shishegaran’s introduction of nonart (what Burger terms “life”) into the realm of art was mainly aimed at liberating art’s autonomy from the hard shell of “institutional autonomy.” Instead of producing yet another work which would reproduce accepted standards of art-making, Shishegaran reintroduces art as a set of social relations, highlighted by his emphasis on mechanisms of socialization (through his use of the medium of poster) and institutionalization (by his persistent engagement with newspaper critics). It was through such an avant-garde call for a radical redefinition of art that Shishegaran managed to demonstrate a way out of the false binary between the “Western” and the “local,” a false binary that had long stranded Iranian modernism.

On August 21, 1977, a few months after the production of ART+ART, Young Ettela’at Weekly published a short story titled “Free Wedding Card Design.” It read: “Koorosh Shishegaran … has embarked on a new project: to design free wedding cards for people.” The artist announced that the project would last for one year and that “this period of one year is itself a work of art by me.” He also gave a telephone number. Like revolutions, weddings are about creating a new future, bringing about a new generation, and welcoming a new dawn—at least, that is the intention. However, the new horizon that Shishegaran opened for autonomous art in Iran was soon blocked off. A year later, independent art found itself in the throes of a revolution—a revolution that on the one hand officially welcomed kitsch as “the art of the people,” and on the other hand ushered in a right-wing avant-garde obsessed with “the aestheticization of blood and martyrdom.”

Ettela’at newspaper, March 16, 1977, 41. All translations from Persian are mine, except when otherwise stated.

“Deductive structure” is a term first used by Michael Fried in his discussion of postwar American abstract painting. “One of the most crucial formal problems” of the postwar period, according to Fried, was “that of finding a self-aware and strictly logical relation between the painted image and the framing edge.” Cited in Maria Gough, Artist as Producer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 47.

Shahla Yeganeh, “A Painter with a New Message: Interview with Koorosh Shishegaran,” Roodaki 19 (1973): 25.

Koorosh Shishegaran, artist’s statement for the second installment of “Reproductive Art” at Mes Gallery, 1973.

Interview with Koorosh Shishegaran, Ferdowsi 1141 (December 1973): 18.

For a philosophical account of the ontology of technological print and its significance in art since conceptualism, see Peter Osborne, “Infinite Exchange: The Social Ontology of the Photographic Image,” Philosophy of Photography 1, no. 1 (March 2010): 59–68.

Jalil Ziapour, “Painting,” Khoroos Jangi (The Fighting Cock) 2 (1949): 12.

Terry Smith, “The Provincialism Problem,” Artforum 12, no. 1 (September 1974): 54–59; reprinted in Journal of Art Historiography 4 (June 2011).

Ziapour, “Painting,” 13.

Smith, “The Provincialism Problem.”

Karim Emami, “Saqqakhaneh School Revisited,” Saqqakhaneh (exhibition catalogue), Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, 1977, reprinted in Iran Modern (exhibition catalogue), Asia Society Museum, 2014, 230. (Written originally in English by Emami.)

Shiva Balaghi, “Iranian Visual Arts in ‘The Century of Machinery, Speed, and the Atom’: Rethinking Modernity,” in Picturing Iran: Art, Society and Revolution, eds. Shiva Balaghi and Lynn Gumpert (London: I. B. Tauris, 2002), 24.

On the political construction of authenticity and Iranian-ness in the context of the 1960s and ’70s, see Ali Mirsepassi, Transnationalism in Iranian Political Thought: The Life and Times of Ahmad Fardid (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming in 2017).

Hamid Keshmirshekan, “Neo-Traditionalism and Modern Iranian Painting: The Saqqa-khaneh School in the 1960s,” Iranian Studies 38, no. 4 (December 2005): 613.

For a scathing contemporary critique of Pope’s ahistorical approach to art history, see Meyer Schapiro’s review of A Survey of Persian Art: From Prehistoric Times to the Present in Art Bulletin 23, no. 1 (March 1941): 82–86.

In his recent book Tahavvolat-e Tasviri-e Honar-e Iran: Barrasi-e Enteghadi (Visual Transformations of Iranian Art: A Critical Survey) (Tehran: Nazar Publishers, 2016), Siamak Delzendeh makes a point by trying to read major transformations of modern Iranian art as a derivative of Pope’s theory of the “decorative” in the art of Iran. Despite his frequent references to interesting archival documents, Delzendeh nonetheless homogenizes a diverse history and leaves some ideological constructions unchecked.

For Corbin, Iran manifested an authentic mode of spirituality that he termed “Iranian Islam”—a transhistorical trajectory “reaching from the ancient Persian prophet Zoroaster through the gnostic prophet Mani and spanning the medieval philosophers Suhrawardi and Mulla Sadra” (Steven M. Wasserstrom, Religion after Religion: Gershom Scholem, Mircea Eliade, and Henry Corbin at Eranos, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999, 134). In the early 1970s, one of Corbin’s chief disciples, Daryoush Shayegan, was a regular lecturer at Hunarkadeh, advising students on “spiritual” manifestations of “Iranian Islam” in the country’s arts.

Negar Azimi, “Interview with Kamran Diba,” Iran Modern (exhibition catalogue), Asia Society, 2013, 80.

There is no time and space here to go into detailed formal analysis of Saqqakhaneh artworks to demonstrate how identity politics is reflected formally at the level of picture plane in these works. That is a task I set out for myself in another article that is yet to published called “How Anti-Colonial Art Served Authoritarian Nationalism: Modernism, Vernacular Culture and the Iranian State.”

Jalal Al-e Ahmad, “Tokhm-e Se Zarde-ie Panjom” (The Fifth Triple-Yolk Egg), in Karname-ie Se Saleh (Three-Year Recapitulation) (1968), reprinted in Al-e Ahmad, Adab va Honar-e Emrooz-e Iran (Iran Contemporary Art and Literature), vol. 3, ed. Mostafa Zamaninia (Tehran: Mitra, 1994), 1386.

Ruin Pakbaz, Talar-e Iran (Iran Gallery) (Tehran: Ministry of Arts and Culture, 1976), 5.

Peter Burger, Theory of the Avant-Garde (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984), 49.

Ayandegan newspaper, April 10, 1977, 6.

Rastakhiz newspaper, republished in Pages 6 (October 2007): 111.

Ayandegan newspaper, March 26, 1977, 6.

Ayandegan newspaper, April 10, 1977, 6.

Category

Subject

An earlier version of this essay was presented at the conference Artists’ Critical Interventions into Architecture and Urbanism (University of Warwick, July 15–16, 2016). I would like to thank the organizers and participants, particularly David Hodge, whose comments were instrumental in the formation of this essay. I am also grateful to Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, who first unearthed ART+ART in 2007 in the sixth volume of their publication Pages. Images of works by Koorosh Shishegaran and newspaper clippings are reproduced here courtesy of the artist.