The current rolling crises of liberal democracy has renewed the significance of formal critique as a critique of forms. This critique careens forward in spasms; sputtering into vision as the governing geometry of market-nation-state lurches and warps, seeking to mend breeches and to accommodate shifts in prevailing conditions.

This critique can be thought of as formalism at, or on, the frontier. It is like twentieth-century formalism insofar as it seeks concreteness and the underlying matter of things. It is crucially unalike, however, as formalism at, or on, the frontier cannot but confront the ethical as integral to mattering in and of itself.

Sven Lütticken has recently discussed such a renewed formal critique—by recalling the presentation of the aesthetic in German Idealism as an obscure and magical substance that somehow flows across - and recconnects -the divorced realms of reason and sense, subject and object, the ethical and the material. Responding to Natasha Ginwala’s recent Contour Biennale, entitled “Justice as a Medium,” Lütticken locates the law as art’s “uncanny doppelganger”—noting a proliferation of artists’ projects that address, mimic, and intervene in the matters of the law.1

Speaking in classical terms, the arts as the proper field of the aesthetic resolve this division of things with events of transcendence that supersede the work of reason. Meanwhile, the law is the domain of an unending reasonable effort to suture together a fallen and divided world; to put things right and to make things just.

What formalism at, or on, the frontier does is to rotate or reorchestrate the deployment of this suturing aesthetic. What is radical in the center may not be so from the periphery. Where the courts of law seek to maintain justice for some, for others they maintain a separation from the very possibility of appearance within the dominion of justice. A Palestinian youth cannot reasonably be heard in the Jerusalem municipal courts, the geontological.2 claims of indigenous belonging cannot testify under Australian tort law, the slow violence of workplace sexual harassment and domestic violence rarely reaches prosecution, and police summarily execute people of racial minorities without losing their jobs, etc. Such are the differential arrangements of ethical sense-making across globalizing systems.

Above all—as I’ve argued elsewhere3—the frontier is an artifact of modernity that most concerns its modes of contact. The frontier is the place where the soaring ideals of the Enlightenment touch down and slow to a grind against the earthly contingency of global expansion. In this morphology of touch, exposure, and exchange, the frontier signifies how modernity’s outside is produced, exploited, and policed.

From this formal view of the frontier—as demonstrated by artists working at, and on, the frontier—it is possible to chart a fourfold articulation. That is, a cosmology of time, being, and belonging produced through the fourfold categories of the natural, the female, the racial, and the prior.

This fourfold articulation acts as an interleaved and hyperbolic matrix, legislating the proper social body of Man (homo economicus) and its wastes. It is the fine sieve through which the extraction of surplus today takes place as a high-intensity, offshored, hedged, and public-private leveraged operation, leeching the sacrificial economies of the fourfold through the toxicity of the sovereign construct. Articulation is an operational concept culled from within this cosmology, but which may yet be useful in untangling its parts.

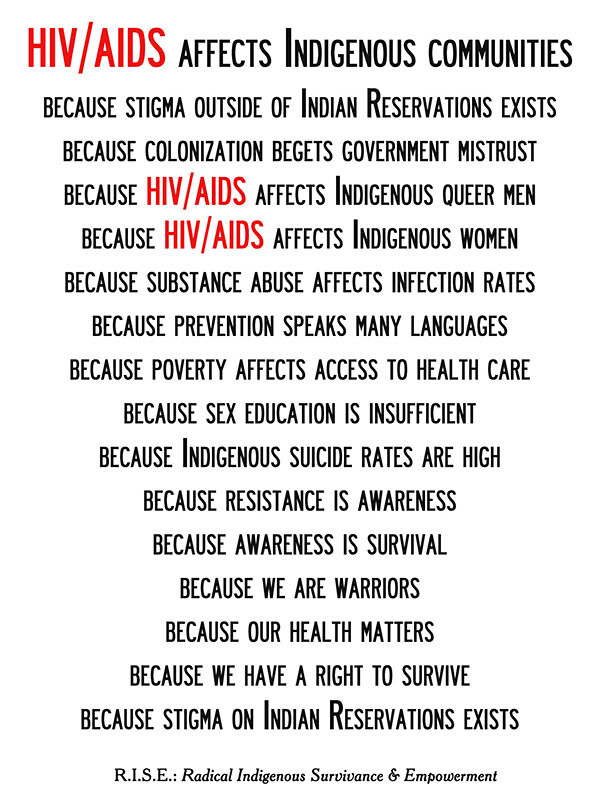

Demian DinéYahzi’ & R.I.S.E.: Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment, HIV/AIDS Affects Indigenous Communities, 2014. Color print on paper, 29.7 x 42cm, exhibition copy. Courtesy of the artist and R.I.S.E.: Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment.

The Fourfold

The formalism of arts at, or on, the frontier is most emphatically not reductive in the abstract. This is not to say that it is maximalist, or necessarily prone to excess. Like the art-historical Art Concret, this formalism is driven to seek truth through matter, although emphatically not through a universalising vocabulary. Its concreteness lies within its positionality along enmeshed chains of value, and not within a concreteness in the abstract.

The posters, T-shirts, and agitprop of Demian DinéYahzi’, for example, rebel against both the macro-social erasure of First Nations Americans, as well as his own specific conditions as a young, queer Diné artist in the present-day vortex of art professionalization. These brilliant images are clearly intended as a self-production of “survivance,” and are constantly updated at the the Tumblr blog Bury My Art At Wounded Knee / Blood & Guts In The Art School Industrial Complex.4

Such a concrete positionality also drives the painting of Shan artist Sawangwongse Yawnghwe. Trained in Canada and Italy—in exile from Burma—his painting since the passing of his father has depicted episodes from memory, from family photographs, from books on the ongoing strife of Burmese independence, from present-day NGO publications, and from what Yawnghwe calls the “Peace Industrial Complex.”

Upon completing a particularly gestural series of paintings, Yawnghwe was asked why he had “burdened” the canvasses with the names and dates of flash points in Burmese and Shan minority history. “Because it’s my life,” he responded.

Although positionality draws art into the narrative world of a lifetime, it is not to be mistaken for the categorical formations of identity. As the fourfold articulation shows, this can never be its object and cannot serve its interests. Formalism at, or on, the frontier rebels against interpellation into identitarian tropes, staging instead—through positional concreteness—a refusal of exchangeability.

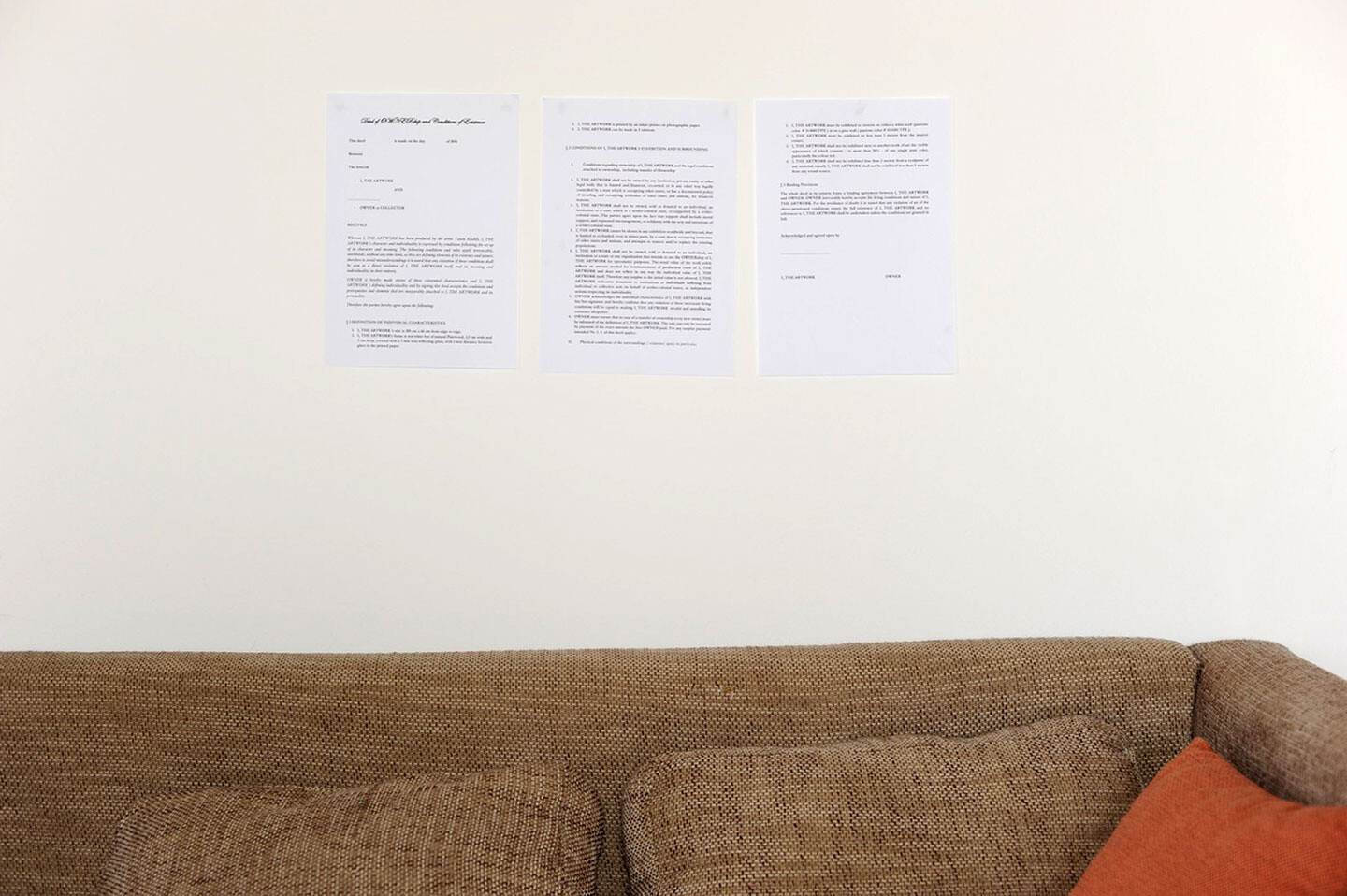

I, The Artwork (2016), by Palestinian artist Yazan Khalili, dramatizes this and cleaves once again to the uncanny alliance of the arts and the law. The work was produced out of the artist’s frustration that an Israeli collector sought to purchase his work, despite its overt anti-occupation expression and despite the campaign of Boycott Divestment and Sanctions called by Palestinian civil society.

In response, Khalili worked with a lawyer to draft a contract—given as a “Deed of Ownership and Condition of Existence”—that forbade the artwork to be owned or controlled by an occupying or settler-colonial power, or supporters thereof. With the phrase “I, The Artwork,” Khalili vested the contract—exhibited as a photograph—with corporate personhood, assigning to it the moral rights usually held by an author.

Although it does not exhibit the usual insignia of militancy, Khalili’s I, The Artwork is nonetheless a maximally rebellious image. The shift this indicates in the Palestinian militant image—from the 1970s to now, and from the AK-47 to the written contract—is instructive in grasping postwar shifts among the coordinates of market-nation-state as seams of global governance. What both share, however, is a refusal of exchangeability—the inability to be substitutable into a particular system or order of things.

The unexamined significance of modes of exchange is the topic of Kojin Karatani’s dazzling recent synthesis The Structure of World History: From Modes of Production, to Modes of Exchange (2014). His core argument is that a modes-of-exchange analytic offers powerful explanations of human social formations globally, and among other things reveals the archaic and ongoing structures of plunder that always underwrite the market-nation-state.

As Karatani explains: “The problem is, insofar as you look at material processes or economic substructures from the perspective of modes of production, you will never find the moral moment.”5

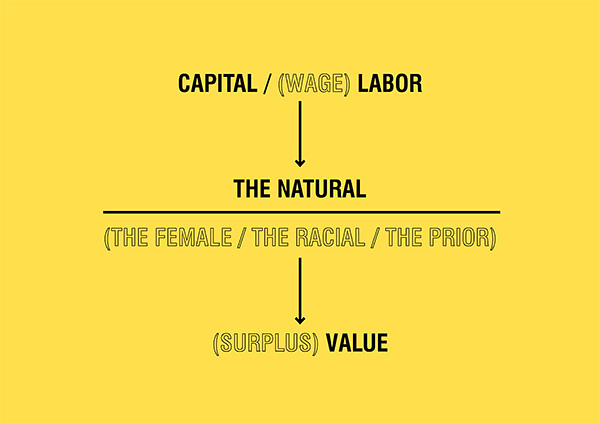

Through a modes-of-exchange analytic, the Marxian value chain may be turned upon its side—revealing the fourfold categories as in fact produced by the classical accounting of value. In this calculation—shown in Schema 1 below—value is simply that which is created where the agency of capital and labor act upon a disenchanted nature.

Here, the natural is a placeholder for all that is acted upon by value-creation, and as such it conceals the fourfold articulation that continues as the female, the racial, and the prior. All of these categories arise in what Marx called “primitive accumulation” and, counter to this title, all are in fact ongoing in the social fabric of the market-nation-state.6

A recent body of literature attests to this and has challenged the Marxian account of primitive accumulation, demonstrating the creation of the fourfold categories as crucial to the (ongoing) formation of market society.

Sylvia Federici, for example, has examined the dramatic persecution of peasant women in the Middle Ages—expunging pagan knowledges and instituting un-valued reproductive labor.7 Denise da Silva has examined the basis of blackness and the racial in the unaccounted-for value of enslaved labor in the nineteenth-century price of cotton, and Fred Moten has examined the impact of this violent ellipsis in Marx’s account of the commodity form.8

Distinct from the racial, Glen Sean Coulthard has also recently critiqued the chronopolitics of “primitive accumulation,” demonstrating the present-tenseness of disposession to indigenous communities in Canada.9 In addition, Elizabeth A. Povinelli has addressed the “governance of the prior” as the arrangement by which settler and European societies designate themselves with/in development as the time of value-creation, and indigenous societies as ahistoric.10

At issue is the fundamental operation of “primitive accumulation” not as a mode of production, but as a mode of exchange in the form of plunder. As an existential architecture of belonging, owning, and obligating, the fourfold charts a cartography of dispossession that readily adapts to cybernetic innovations in the technosphere. Its technologies of dispossession remain foundational, if intensified. And as such, it is the fourfold that continues to shape the conditions of possibility of the arts, the law, and of expressivity in general.

Before moving onto the notion of articulation, there are two short asides.

The first is to note that the conjunction of market-nation-state is borrowed from Karatani, who expresses these as a series of interdependent Borromean rings, also borrowed from Lacan. Whereas Karatani uses the term “capital,” the term “market” is used here in order to prioritize the competing and multiple systems of capital that are differentially territorialized and socialized. Thinking of Australia for example, the competing interests of tourism and mineral markets continually force fascinating contortions within the state and national bodies that seek to reconcile them.

Secondly, formalism is distinguished as “at, or on” the frontier in order to prioritize the asymmetrical ways in which the matrices of the fourfold are encountered. For example, Australian artist Rachel O’Reilly utilizes the smooth space of computer-aided design and the singularity of poetic language to dramatize the non-exchangeability of ecological and social spaces into the extraction-friendly business plans of state bureaucracy.

In a similar mode, and also from Australia, Tom Nicholson’s recreated sixth-century Byzantine mosaics explore chromatic exchange among small tesserae tiles as a means to piece together the horizons of Australian and Israeli settler expropriation. Both practices are dedicated to addressing the folds of the frontier, to drawing forward practices of dispossession that are often obscured from the hegemonic standpoint, and to unraveling their operations. Both artists acknowledge at the outset their differential position in this work compared to that of an indigenous artist, from a local or nonlocal area, for example. This sensitivity to how positionality capacitates practices differently is what “at, or on” the frontier seeks to preserve.

Yazan Khalili, I, The Artwork, 2016. Photographic print 120 x 79.2cm. Contract documented within the artist studio; legal consultation provided by Martin Heller. Commissioned by Riwaq Biennial with support of Mophradat. Photo: Yazan Khalili. Courtesy of the artist.

Articulation

Within conditions of crisis—such as those currently witnessed across the NATO sphere in tandem with its immediate adversaries—expressivity spikes. This may be witnessed in a rise in mass public gatherings, assemblies, and riots; or in the extraordinary 2016 profits of Facebook, for example. The renewed critique of forms calls for a critique of expressivity as that which under law denotes the realm of artistry, and as “freedom of expression” has become such a flash point within liberal democratic malaise.11 To this, the concept of articulation responds with a view from the long durée.

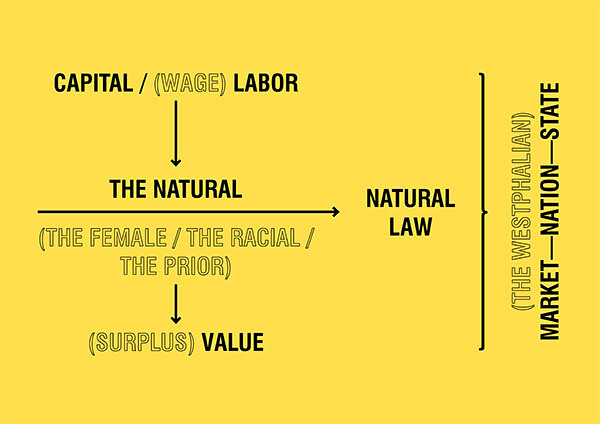

In the early 1500s, when the conquistadors returned from the “Indies,” many flocked to the Convent of St. Esteban in Salamanca, Spain to confess. In a brilliant essay on the origins of international law, legal scholar and former diplomat Martti Koskenniemi systematically traces how the crisis of faith provoked by colonial plunder—heard as confession—was resolved by the Church’s formalization of an ethical offsetting between the public and the private. This divorce—naturalized as the basis of Natural Law—continues to underpin the international system, formalized through the institutions of the Westphalian nation-state system, as diagrammed in Schema 2.

This politico-theological fix was led by the prima (senior) professor of theology at the University of Salamanca, Francisco de Vitoria (c.1492–1546). The indisputable violence of dispossession in the “Indies”—without a justification for war—produced a double bind for Vitoria, caught between the testimonies of confession and the indisputable command of his king, Charles V.

Although convinced of the innocence of the conquistadors’ victims—expressing in a letter that news of the colonists’ acts “freezes the blood in my veins”—Vitoria simultaneously never doubted European superiority, or the right of conquistadors to encroach upon the territories of the New World.12

Vitoria’s solution was an innovation in categorical terms, dividing human affairs into dominium iurisdictious (public law), and dominium proprietas (private ownership). The upshot, in Koskenniemi’s words, was “a politico-theological vocabulary that would extend a certain idea about the justice of private relationships on a universal basis.”13 In short, the conquistadors were merely pursuing their justified interests in private property.

This fundamental break—governing the global present as Natural Law—institutes a cosmos of ethical two-stepping, disconnecting certain moral chains and facilitating other value chains focused upon access to material wealth.

The fourfold articulation therefore takes place as an arts of dispossession wrought through the production and erasure of certain joints; turning taps on and off; permitting flows there, and accumulations here. In the general sense, this systemic work of producing and erasing connections can be called “articulation,” and thus Khalili’s I, The Artwork can be grasped as a counterpractice of an arts of articulation, refusing to form a conjunction with the ideological space of settler capital.

Zooming out, Megan Cope’s sculptural installation RE-FORMATION (2016) utilizes a similar set of coordinates in diagramming territorial dis-articulation as it occurs in Quandamooka country in South-East Queensland, Australia. The work mimics a midden—an indigenous architecture of accumulated shell and bone fragments—based upon the black mineral sands and white silica sands that are separated through extraction by Belgian multinational Silbelco.

The oyster shells of the black-sand midden are laboriously hand-cast in concrete—a reference to the mass destruction of middens by 1800s convict labor that burned the shells to extract lime for brick-and-mortar dwellings. When exhibited in Jerusalem, with the Al-Ma’mal Foundation, the black sand was replaced by the unmistakable rusty terra rossa dirt of Palestine’s central highlands, connecting up global shorelines of European colonial encroachment.

The territorial dimension of these articulations also emerges in the recent bronze sculptures of Golan artist Randa Maddah, such as A Hair Tie (2016). The works were produced from the experience of Majdal Shams, a mountain village in the Occupied Golan that is perched above the Israeli fence line to Syria, and just southeast of a military base known as “the eye of the State.” In correspondence with Maddah shortly before his recent passing, the English critic John Berger wrote:

I want to try to describe to you how I place it [the sculpture] as a spectator in my imagination. I return to Palestine and I look at the earth I’m walking on: it’s grasses, its boulders, its ditches, its tangled undergrowth, its corpses, the roots of its trees, its pools, and I think that what they endure as fragments, not of the earth, but of a homeland, is expressed in the figures you create. Through you the self-portraits of these territorial particles come into being. It is as if you hold a pebble from the Golan Heights in your left hand and with your right draw what is inside it.14

The terrestrial dimension of the term “articulation” is perhaps necessary. Within a Marxian genealogy it can be traced from its appearance within the late writings of Grundrisse, to the schisms of 1970s Anglo-Althusserian debates, and to the 1980s cultural turn of Stuart Hall. In the original German it appears as Gliederung—derived from glied, meaning “limb”— suggesting a system governed by connections in a sense similar to that of the Latin artus of articulation, meaning to join or fit together.

See, for example, Marx’s structural schema given in Grundrisse: “The coexistance of limbs [membres] and their relations in the whole is governed by the order of a dominant structure which introduces a specific order into the articulation [Gliederung] of the limbs [membres] and their relations.”15

A particular focus on articulation didn’t appear in historical materialist discourse until the 1970s, however, and as part of a number of system-scaled maneuvers that sought to grapple with the inadmissibly differential function of the global market system from the point of view of the Third World, or development’s “peripheries.”16

Stuart Hall’s subsequent use of the term aimed to prise open the doctrinal consideration of ideology towards a greater field of “culture” that would permit the significance of the racial to be grasped within a distributive analysis and towards a redistributive project. In a similar operation, articulation is used here to schematize the cosmology of market-nation-state as formed by the articulations and disarticulations of the fourfold. Emancipatory projects that seek transformation—without reckoning with this structure—will struggle to avoid reasserting the harm of its categorical form.

Improvisational Realism

As I touched upon earlier, there is a difference among practices working at, or on, the frontier. What appears to some as a fairly smooth world of opening airport gates, opening bank accounts, and pleasant social interactions, to others is encountered as a world of slamming doors.

What Karrabing Film Collective call their “Improvisational Realist” practice navigates the arts of articulation from this latter point of view. Their film and installation works are driven by the exhaustive labor of survivance amid the fourfold articulation. As such, obtaining funds for national and international mobility, the infrastructures of passports, and the vocabularies of arts and bureaucratic worlds are all considered an integral part of their film and installation-making practice.

At the far-stretched frontiers of the Australian market-nation-state, governance can appear surreal—even psychedelic—as in Karrabing’s recent film Wutharr: Saltwater Dreaming (2016). The film plays out across Karrabing’s homelands, the Belyuen community, and conflicting explanations of the disastrous event of a boat-motor breakdown. Its narrative crisscrosses the accounts of three Karrabing members: 1) Trevor, who sees a jealous world of indigenous geontological ancestry; 2) Jojo, who sees a disciplining world of Christian virtue; and 3) Rex, who sees an exhausted material world of poverty, rusty wiring, and far-off sources of replacement. All are experienced as equally real—the settings of dizzying patterns of interference as they merge and subside.

Ultimately, the state intervenes to put things in place. This, however, is surreal in its own way—as the fine for setting off a rescue flare without proper safety equipment is AUD$30,000, levied upon indigenous people who receive $250 a fortnight in state subsidy.

The enormous scale, adaptability, and force of the fourfold articulation is hard to overestimate. Its centuries-long processes of world-making and world-destroying are quick to put the lie to shallow opposition and ill-worked-through revolutionary bluster.

As such, the expressiveness of articulation as a counterpractice is most emphatically not the expressiveness of declarative sovereignty. It is not summoned through proclamations; its subject is not the ideal artist in a self-realizing mode—a mode also heavily prioritized through corporatized social media.

The emergent emancipatory sovereignties of formalism at, and on, the frontier are perhaps no sovereignty at all. It may just be artists—in the guise of people—navigating the tender footholds of the present, and grasping for some stronger base upon which to stand. Not in the sense of self-determination and abstract freedoms, but as the world that emerges in the social and terrestrial capacity to form one’s own dependencies.

Sven Lütticken, “Legal Forms, Value Forms, Forms of Resistance,” Hearings: The Online Journal of Contour Biennale, January 12, 2017 →.

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Geontologies, a Requiem for Late Liberalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

Vivian Ziherl, “On the Frontier, Again,” e-flux journal 73 (May 2016) →.

See →. “Survivance” is a term advanced by Anishinaabe cultural theorist Gerald Vizenor in his book Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Surviviance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

Kojin Karatani, The Structure of World History: From Modes of Production to Modes of Exchange (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), xix.

Karl Marx, “Chapter Twenty-Six: The Secret of Primitive Accumulation,” Capital, vol. 1, 1867.

Sylvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (Oakland: AK Press, 2004).

Denise da Silva, “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value,” e-flux Journal 79 (February 2017) →. Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003); in particular, see the chapter “Resistance of the Object: Aunt Hester’s Scream.”

Glen Sean Couthard, Red Skins White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

The artist project Agency, by Kobe Matthys, studies the category of expressivity in the court case Sheldon and Barnes v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, a dispute over artists’ rights and property in 1930s.

Martti Koskenniemi, “Colonization of the ‘Indies’—The origin of international law,’ lecture at the University of Zaragoza, December 2009.

Ibid.

See →.

Marx, Grundrisse, 1857.

The Anglo-Althusserian focus upon “articulation” in fact emerged out of Althusser’s reception of Mao’s On Contradiction, where it indicated a conjunction between modes of production.

Subject

Dedicated with a huge debt of thanks to the Al-Ma’mal Foundation in Jerusalem and Karrabing Film Collective in Belyuen. Particular scholarly thanks to Denise Ferreira da Silva and Elizabeth A. Povinelli, and in particular for da Silva’s pointer to de Vitoria. Thanks to Stephen Squibb and Quentin Sprague for further editing, to Ziga Testen for graphic design, as well as to Yumi Maes for enabling the time out with writing. An earlier edition of the Fourfold Articulation schema appears within Feminist Takes by Antonia Majaca and tranzitdisplay, with thanks to Rachel O’Reilly and Jelena Vesic for editorial guidance there.