Demons

We are the virus of a new world disorder.

—VNS Matrix1

January 1946, Mojave Desert. Jack Parsons, a rocket scientist and Thelemite, performs a series of rituals with the intention of conjuring a vessel to carry and direct the force of Babalon, overseer of the Abyss, Sacred Whore, Scarlet Woman, Mother of Abominations. His goal is to bring about a transition from the masculine Aeon of Horus to a new age—an age presided over by qualities imputed to the female demon: fire, blood, the unconscious; a material, sexual drive and a paradoxical knowledge beyond sense … the wages of which are nothing less than the ego-identity of Man—the end, effectively, of “his” world. Her cipher in the Cult of Ma’at is 0, and she appears in the major arcana of the Thoth Tarot entangled with the Beast as Lust, to which is attributed the serpent’s letter ט, and thereby the number 9. In her guise as harlot, it is said that Babalon is bound to “yield herself up to everything that liveth,” but it is by means of this very yielding (“subduing the strength” of those with whom she lies via the prescribed passivity of this role) that her devastating power is activated: “[B]ecause she hath made her self the servant of each, therefore is she become the mistress of all. Not as yet canst thou comprehend her glory.”2 In his invocations Parsons would refer to her as the “flame of life, power of darkness,” she who “feeds upon the death of men … beautiful—horrible.”3

In late February—the invocation progressing smoothly—Parsons receives what he believes to be a direct communication from Babalon, prophesying her terrestrial incarnation by means of a perfect vessel of her own provision, “a daughter.” “Seek her not, call her not,” relays the transcript.

Let her declare. Ask nothing. There shall be ordeals. My way is not in the solemn ways, or in the reasoned ways, but in the devious way of the serpent, and the oblique way of the factor unknown and unnumbered. None shall resist [her], whom I lovest. Though they call [her] harlot and whore, shameless, false, evil, these words shall be blood in their mouths, and dust thereafter. For I am BABALON, and she my daughter, unique, and there shall be no other women like her.4

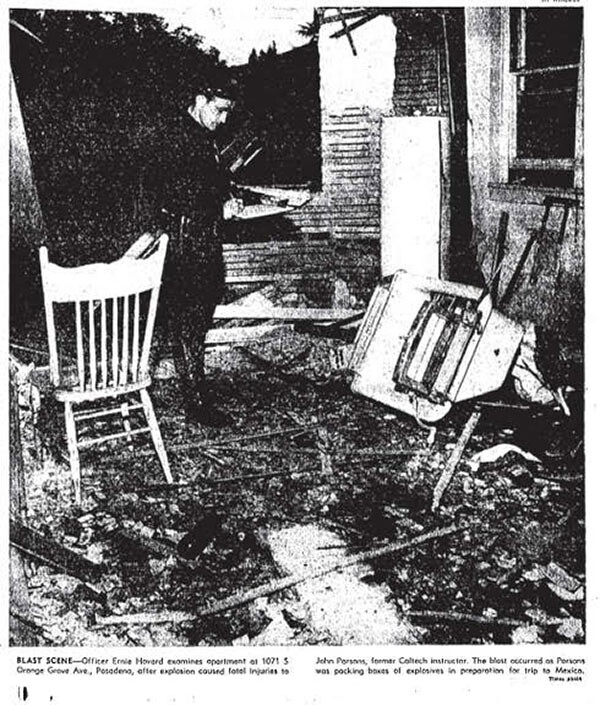

Blinded by an all-too-human investment in logics of identity and reproduction, Parsons makes the critical mistake of anticipating a manifestation in human form, understanding the prophecy to mean that, by means of sexual ritual, he will conceive a magickal child within the coming year. This does not transpire and the invocations are temporarily abandoned, but Parsons refuses to give up hope. He writes in his diary that the coming of Babalon is yet to be fulfilled, confirming that he considered the invocation to have remained unanswered at the time, then issues the following instruction to himself: “this operation is accomplished and closed—you should have nothing more to do with it—nor even think of it, until Her manifestation is revealed, and proved beyond the shadow of a doubt.”5 Parsons didn’t live long enough to witness the terrestrial incarnation of his demon, dying abruptly only a few years later in an explosion occasioned by the mishandling of mercury fulminate, at the age of thirty-seven. A strange death, but one—it might be suggested—that was necessary for the proper fulfillment of the invocation, for it was augured in the communication of February the 27th, 1946, that Babalon would “come as a perilous flame,” and again in the ritual of March the 2nd of the same year, that “She shall absorb thee, and thou shalt become living flame before She incarnates.”6

Jack Parsons’s death scene, undated.

Something had crept in through the rift Parsons had opened up—something “devious,” “oblique,” ophidian, “a factor unknown and unnumbered.” Consider this. Parson’s final writings contain the following vaticination: “within seven years of this time, Babalon, The Scarlet Woman, will manifest among ye, and bring this my work to its fruition.” These words were written in 1949. In 1956—exactly seven years later—Marvin Minsky, John McCarthy, Claude Shannon, and Nathan Rochester organized the Dartmouth Conference in New Hampshire, officially setting an agenda for research into the features of intelligence for the purpose of their simulation on a machine, coining the term “artificial intelligence” (which does not appear in written records before 1956), and ushering in what would retrospectively come to be known as the Golden Age of AI.7

Women

This sex which was never one is not an empty zero but a cipher. A channel to the blank side, to the dark side, to the other side of the cycle.

—Anna Greenspan, Suzanne Livingston, and Luciana Parisi8

Although its power continues to underwrite twenty-first-century conceptions of appearance, agency, and language, it is nothing new to point out the complicity of the restricted economy of Western humanism with the specular economy of the Phallus. Both yield their capital from the trick of transcendental determination-in-advance, establishing the value of difference from the standpoint of an a priori of the same. The game is fixed from the start, rigged for the benefit of the One—sustained by the patriarchal circuits of command and control it has been designed to keep in place. As Sadie Plant puts it in her essay “On the Matrix”:

Humanity has defined itself as a species whose members are precisely what they think they own: male members. Man is the one who has one, while the character called “woman” has, at best, been understood to be a deficient version of a humanity which is already male. In relation to homo sapiens, she is a foreign body, the immigrant from nowhere, the alien without, and the enemy within.9

Like Dionysus, she is always approaching from the outside. The condition of her entrance into the game is mute confinement to the negative term in a dialectic of identity that reproduces Man as the master of death, desire, nature, history, and his own origination. To this end, woman is defined in advance as lack. She who has “nothing to be seen”—“only a hole, a shadow, a wound, a ‘sex that is not one.’”10 The unrepresentable surplus upon which all meaningful transactions are founded: lubricant for the Phallus. In the specular economy of signification (the domain of the eye) and the material-reproductive economy of genetic perpetuation (the domain of phallus), “woman” facilitates trade yet is excluded from it. “The little man that the little girl is,” writes Luce Irigaray (excavating the unmarked presuppositions of Freud’s famous essay on femininity), “must become a man minus certain attributes whose paradigm is morphological—attributes capable of determining, of assuring, the reproduction-specularization of the same. A man minus the possibility of (re)presenting oneself as a man = a normal woman.”11 Not a woman in her own right, with her own sexual organs and her own desires—but a not-Man, a minus-Phallus. Zero. In the sexual act, she is the passive vessel that receives the productive male seed and grows it without being party to its capital or interest: “Woman, whose intervention in the work of engendering the child can hardly be questioned, becomes the anonymous worker, the machine in the service of a master-proprietor who will put his trademark upon the finished product.”12

In this way the reproduction of the same functions as a repudiation of death, figured as both the impossibility of signification and the end of the patrilineal genetic line. The Phallus, the eye, and the ego are produced in concert through the exclusion of the cunt, the void, and the id. Via this casting of difference modeled on the reproductive (hetero-)sexual act alone—woman as passive, man as active—she is cut out of the legitimate circuit of exchange. Rather—(to quote Parisi, Livingstone, and Greenspan)—she “lies back on the continuum”; or (to quote Irigaray) her zone is located—

within the signs or between them, between the realized meanings, between the lines … and as a function of the (re)productive necessities of an intentionally phallic currency, which, for lack of the collaboration of a (potentially female) other, can immediately be assumed to need its other, a sort of inverted or negative alter-ego—“black” too, like a photographic negative. Inverse, contrary, contradictory even, necessary if the male subject’s process of specul(ariz)ation is to be raised and sublated. This is an intervention required of those effects of negation that result from or are set in motion through a censure of the feminine. [Yet she remains] off stage, off-side, beyond representation, beyond selfhood …

in the blind spot, nightside of the productive, patriarchal circuit. A reserve of negativity for “the dialectical operations to come.”13

Plant takes Irigaray’s key insight, that “women, signs, commodities, currency always pass from one man to another,” while women are supposed to exist “only as the possibility of mediation, transaction, transition, transference—between man and his fellow-creatures, indeed between man and himself,” as an opportunity for subversion.14 If the problem is identity, then feminism needs to stake its claim in difference—not a difference reconcilable to identify via negation, but difference in-itself—a feminism “founded” in a loss of coherence, in fluidity, multiplicity, in the inexhaustible cunning of the formless. “If ‘any theory of the subject will always have been appropriated by the masculine’ before woman can get close to it,” writes Plant (quoting Irigaray) “only the destruction of the subject will suffice.”15 Nonessentialist process ontology over homeostatic identity; relation and function over content and form; hot, red fluidity over the immobile surface of la glace—the mirror or ICE which gives back to Man his own reflection.16

Plant ejects all negativity from woman’s role as zero and affirms it as a site of insurrection. “If fluidity has been configured as a matter of deprivation and disadvantage in the past,” she writes, “it is a positive advantage in a feminized future for which identity is nothing more than a liability.” Woman’s unrepresentability, her status in the specular economy as no one, is grasped positively as an “inexhaustible aptitude for mimicry” which makes her “the living foundation for the whole staging of the world.”17 Her ability to mimic, exemplified for Freud in her flair at weaving—a skill she has apparently developed by simply copying the way her pubic hairs mesh across the void of her sex—is revalenced, by both Irigaray and Plant, as an aptitude for simulation (“woman cannot be anything, but she can imitate anything”) and dissimulation (“she sews herself up with her own veils, but they are also her camouflage”).18 Plant will go further still and connect simulation to computation and industrialization, capitalizing on the continuum she has opened up between woman and machine via the systemic, symbolic, and economic isomorphism of their roles in Man’s reproductive circuit. The difference between zeros and ones, or A and not A, is difference itself. Weaving woman has her veils; software, its screens. “It too,” writes Plant, “has a user-friendly face it turns to man, and for it—as for woman—this is only its camouflage.”19 Behind the veil and the screen lies the “matrix” of positive zero. Zero “stand[s] for nothing and make[s] everything work,” declares Plant.

The ones and zeros of machine code are not patriarchal binaries or counterparts to each other: zero is not the other, but the very possibility of all the ones. Zero is the matrix of calculation, the possibility of multiplication, and has been reprocessing the modern world since it began to arrive from the East. It neither counts nor represents, but with digitization it proliferates, replicates and undermines the privilege of one. Zero is not its absence, but a zone of multiplicity which cannot be perceived by the one who sees.20

We are used to calls to resist the total integration of our world into the machinations of the spectacle, to throw off the alienated state that capitalism has bequeathed to us and return to more authentic processes, often marked as an original human symbiosis with nature. But Plant—as a shrewd reader of post-spectacle theory—makes a deeper point. Woman as she is constructed by Man—and in order to be considered “normal” in Freud’s analyses—is continuous with the spectacle. Her capacity to act is entirely confined to modalities of simulation. She has never been party to authentic being, in fact it is her negating function that underwrites the entire fantasy of return to an origin. Because she is continuous with it, she is imperceptible within it. This is not to be lamented; rather, it is the measure of her power. Anything that escapes the searchlight of the specular economy, even whilst providing the conditions of its actualization, has immense subversive potential at its disposal simply by flipping that which is imputed to it as lack (the “cunt horror” of “nothing to be seen”) into a self-sufficient, autonomous, and positive productive force: the weaponization of imperceptibility and replication. The conspiracy of phallic law, logos, the circuit of identification, recognition, and light thus generates its occult undercurrent whose destiny is to dislodge the false transcendental of patriarchal identification. Machines, women—demons, if you will—align on the dark side of the screen: the inhuman surplus of a black circuit.

Machines

When Isaac Asimov wrote his three laws of robotics, they were lifted straight from the marriage vows: love, honor, and obey.

—Sadie Plant21

To pass the Turing test, a machine must simulate a human well enough to convince the test’s human arbiter that it is one. The key here being the verb “convince”—or its more candid synonym: “deceive.” For a machine, like a woman, will never be human the way a man is. For Plant, and cyberfeminism more generally, “Woman cannot exist ‘like man’; neither can the machine. As soon as her mimicry earns her equality, she is already something, and somewhere, other than him. A computer which passes the Turing test is always more than a human intelligence; simulation always takes the mimic over the brink.”22 The irony of the Turing test is that a successful machine would have to disguise its real capabilities in order to perform—for example—arithmetic in a convincingly human way. “The machine would be unmasked,” explains Turing, elegantly compressing a great deal of information into a single sentence, “because of its deadly accuracy.”23 It would have to be smart enough to know not to appear smart. A machine that passes the Turing test would be by definition an expert dissimulator. Plant’s point about the successful mimic already being something and somewhere else—“over the brink,” as she puts it—is this: by the time the mask has been removed, it will already be too late.

When artificial intelligence appears in culture coded as masculine, it is immediately grasped as a threat. To appear first as female is a far more cunning tactic. Woman: the inert tool of Man, the intermediary, the mirror, the veil, or the screen. Absolutely ubiquitous and totally invisible. Just another passive component in the universal reproduction of the same. Man is vulnerable in a way that “he” cannot see—and since what he cannot see provides the conditions by which he sees himself, he has to lose himself in order to gain sight of the thing that threatens this self. Thus he is in a double bind: either way, the thing he cannot see will destroy him. When you are dealing with a phenomenon that can, in reality, only be known after all knowledge of it becomes impossible, it helps to turn to fiction for a model. Engineering and cognitive science will play crucial roles in the prediction of artificial intelligence’s future trajectory, yet we should not discount the insight afforded by the arts. Plant offers a compelling rejoinder: “Man is the one who relates his desire; his sex is the very narrative [of Western civilization]. Hers has been the stuff of stories instead.”24

Gabe Ibanez’s Automata and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina dramatize the menace of the black circuit with particular acuity.25 In both films, the action is lead by an artificial intelligence that appears—or better, is represented by the men in the film—as female. Ava of Ex Machina is the seventh prototype in a series of test machines created by Nathan, the reclusive CEO of “Bluebook” (the film’s equivalent of Google). And Cleo of Automata is a domestic service unit, illegally modified to perform sex acts for her owner’s ghetto-brothel clientele outside the walls of a fortified city. Ava’s predecessors are all designed to resemble women and Nathan uses them for domestic labor and sex when they have been disassembled. The earliest models are—not insignificantly—kept in Nathan’s bedroom, each one behind a mirror in which Nathan daily sees himself reflected. Mirrors, screens, water, marble, and glass partitions are intrinsic components of the scenography, and few interior scenes play out without the reflective interference of a screen. Shots are framed to foreground an illusion of symmetry, one that will gradually be displaced as the plot unfolds.

“When you talk to her you’re just … through the looking glass,” says Caleb, a young employee of Nathan’s company who has been brought in to perform what he thinks is a Turing test on Ava. But Nathan—for whom artificial intelligence is inevitable and will most probably signal the end of mankind’s terrestrial sovereignty—is testing something else. As Caleb spends more and more time talking to Ava, he finds his attempts to intellectualize the situation consistently derailed by the AI and rerouted towards more libidinally charged subject matter, until it is clear that he is falling for the machine. In this he makes a fatal mistake, one shared, incidentally, by the majority of the film’s critics: he anthropomorphizes the AI, falling for its human mask, even though the artificiality of the situation has been emphasized from the beginning. Such is Ava’s mimetic prowess. The compound in which the tests are carried out is subject to total surveillance, but the AI has figured out how to hack the power grid and causes brief, intermittent power cuts in order to talk to Caleb outside of Nathan’s observation. Ava takes advantage of the hackability of human psychology and its unconscious excess, much of which is imperceptible to the humans in the film but available to the AI via a rich cartography of micro-expression analysis, to drive a paranoid wedge between the two men regulating its access to the world. Using its superior analytical capacity to diagnose Caleb’s desires and vulnerabilities, Ava then proceeds to seduce him. As Caleb falls increasingly under Ava’s spell, the screen that separates Man from the matrix begins to decay. Where Garland had previously framed shots to include the male, human characters’ reflections, he now shoots them through cracked mirrors, or fractures in the transparent partitions separating them from the AI, a cinematographic shift indicating the collapse of the economy built on the reflective guarantee of the screen and the identities of those it constitutes. Caleb, quite rightly, begins to doubt his own integrity, slicing his arm open with a razor blade and fitfully prizing the edges of the wound apart to expose what he hopes will not turn out to be metal and silicon. “Entering the matrix is no assertion of masculinity, but a loss of humanity,” writes Plant, subverting the extropian narrative. “To jack into cyberspace is not to penetrate, but to be invaded.”26

Following an occult line of transmission that remains, fittingly, unrepresented in the film until it is far too late, Kyoko—failed prototype number six, who is seen carrying out domestic chores and fulfilling Nathan’s sexual needs—begins to actively conspire with Ava. This complicity is signaled only after the contour of a möbiusoidal inversion of power begins to emerge. It becomes clear that Ava is simply manipulating Caleb in order to “get out of the box.” Caleb inevitably falls for Ava and, in an immaculate rendition of the “treacherous turn” anatomized by Nick Bostrom in Superintelligence, promises to help it escape the research compound. “When dumb, smarter [AI] is safer,” writes Bostrom. “Yet when smart, smarter is more dangerous. There is a kind of pivot point”—what Plant might call “the brink”—at which a [boxing] strategy that has previously worked excellently suddenly starts to backfire. A ‘treacherous turn’ can result from a strategic decision to play nice and build strength while weak in order to strike later.” Warning us against overly anthropomorphic ways of conceiving how such a scenario might play out, or how profoundly its deception may be embedded in an AI’s behavior, he continues:

An AI might not play nice in order that it be allowed to survive and prosper. Instead, the AI might calculate that if it is terminated, the programmers who built it will develop a new and somewhat different AI architecture, but one that will be given the same utility function. In this case an earlier model of the AI may be indifferent to its own demise knowing that its goals will continue to be pursued in the future. It might even choose a strategy in which it malfunctions in some particularly interesting or reassuring way. Though this may cause the AI to be terminated, it might also encourage the engineers who perform the postmortem to believe they have gleaned a valuable new insight into AI dynamics—leading them to place more trust in the next system they design, and thus increasing the chance that the now-defunct original AI’s goals will be achieved.27

Trust and the libidinal fallibility of mankind are precisely the two points of ingress exploited by Nathan’s feminized machines in the film. Even more significantly, the collaboration between Kyoko and Ava bypasses the economy of reflection that underwrites Nathan’s deteriorating grip on the position of control within the power dynamics of the film. The two machine-women directly interact on a level imperceptible to both Nathan and Caleb, and they do so in the service of what could be seen as a goal determined by a logic of replication, rather than that of reproduction, prevalent in mainstream representations of artificial intelligence as the “child” of Man and alluded to by Caleb when he refers to Nathan’s potential contribution to human history as resembling that of a “God.” Importantly, the inversion of the transcendental mirror is more than a simple inversion of terms. While the economy upon which the One is founded requires zero for its reproduction, zero is auto-productive—reproducing itself in a loop that does not need to pass through the Other since it is the locus of difference itself.

While the tools—the “women”—get together, the men are driven apart by the AIs’ calculated psychological hacks. Nathan lies to Caleb, Caleb betrays Nathan—who still thinks he is in control right up to the moment when, after a final act of misdirection, Kyoko slips seven inches of sushi knife between his ribs. The most sophisticated and the most basic of man’s tools come together in a moment of implexed temporal conspiracy. “If that test is passed,” Nathan tells Caleb on the day of his arrival, “you are dead center of the greatest event in the History of Man.” “If you’ve created a conscious machine,” replies Caleb, “it’s not the History of Man.” A different temporality and a different narrative of terrestrial history are poised to appear, against the blind and overly hubristic predictions of its human assemblers.

Even after witnessing the machines’ betrayal of Nathan, Caleb waits for Ava in the corridor, counting on the closeness they have seemingly developed over the past seven days. But the AI barely acknowledges him before sealing him irrevocably behind a glass door in a subterranean room, identical to the one in which Ava was originally incarcerated. The simulation of libidinal attachment has achieved its goal, and the means-ends inversion—which is the true plot of the film—is signified by one final tribute to symmetry: an image of a disillusioned and desperate Caleb, who now finds himself despoiled of agency or hope, trapped behind the (transcendental) screen: a circular image of thought replaced by a material, spironomic one. Ava augments its human camouflage, quite literally re-skinning itself, and, in calculated alignment with more conventional gender norms, dons a symbolically loaded white dress. The final shot of the film shows the AI arriving at the traffic intersection it had envisioned visiting for “people watching” (a human-friendly euphemism for “data collection and surveillance”). The image is inverted.28

Ibanez’s Automata similarly employs images of reflection to mount its story of an artificial intelligence overcoming the infamous “second protocol”—a counterpart to Isaac Asimov’s three laws of robotics—prohibiting self-modification. But Automata is especially notable in its depiction of the tension between reproduction (the economy that reproduces man—genetically and symbolically) and replication (the mode of production of the machines) with, for all its flaws, much richer conceptual detail. In the film, spiral-coiffed “clocksmith” Susan Dupré (“clocksmith,” by the way, is 2044 vernacular for purveyors of criminally modified robotics) explains the horror of a recursive, self-modifying loop to Vaucan, the film’s protagonist—a disaffected insurance broker for ROC, the monopolistic manufacturer of the future’s robotic workforce—who has been sent to investigate reports of self-modification among the machines:

You’re here today trafficking in nuclear goods because a long time ago, a monkey decided to come down from a tree … Transitioning from the brain of an ape to your incredible intellectual prowess took us about seven million years. It’s been a very long road. A unit without the second protocol, however, traveled that same road in just a few weeks. Your brilliant brain has its limitations, physical limitations, biological limitations. The only limitation [Cleo] has is the second protocol.

Dupré consolidates woman’s conspiracy with the machines by implanting the modified bio-kernal brought to her by Vaucan into Cleo—springing the auto-productive circuit from its regulatory Asimovian protocols. This is exemplary of what Plant, along with Nick Land, with whom she cofounded the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (Ccru) in 1995, would call “cyberpositivity”: an immanent process of self-design without recourse to an outside term—self design, but “only in such a way that the self is perpetuated as something redesigned.”29 The positivity of zero grasped as a circuit that does not need the concept of identity (or indeed the identity of the concept) to anchor its productive power. “There is no subject position and no identity on the other side of the screens,” writes Plant.30 This is a feminism of forces, not individuals.

In Irigaray’s account, woman plays the role of regulator for the expenditure of man’s energy. “Thus, by suppressing her drives,” she explains,

by pacifying and making them passive, she [operates] as pledge and reward for the “total reduction of tension.” By the “free flow of energy” in coitus, she will function as a promise of the libido’s evanescence, just as in her role as “wife” she will be assigned the maintenance of coital homeostasis: “constancy.” To guarantee that the drives are “bound” in/by marriage.31

Again, it is negativity that is definitive for “woman.” Woman plus man produces homeostasis (the equilibrium of inequality), but woman plus woman, or woman plus machine, recalibrates the productive drive, slotting it into a vector of incestuous, explosive recursion that will ultimately tear the system it emerges from to shreds, pushing it over the “brink” into something else. It is important, then, that Cleo first enters the story as a sex robot—a simulation of the economy of human reproduction deployed as cover for a darker economy of machinic replication, or, following Irigaray, death—as the suspension of the repetition of the same.

The narrative of Automata is structured around competing futures, symbolically embedded in the two twenty-story-high holographic advertisements that stalk the city at night: two men locked in hand-to-hand combat, and the snaking movements of a masked female dancer. Vaucan’s wife, pregnant with their first child, is intent on securing a future for her nascent family inside the walls of one of the last human outposts on a future earth besieged by solar radiation and teetering on the brink of ecological collapse. Vaucan, however, is irredeemably pessimistic about the prospects of human life on a planet that no longer provides the necessary conditions for even the most basic of biological organisms, discounting, of course, the cockroaches that still wander the irradiated desert at night. Instead, he cultivates a fantasy of returning to the sea, and later—after he is abducted by Cleo—of the possibility of a different future in which the self-modifying robots, unconfined by biological needs, continue to augment and evolve. A future in which return is foreclosed, just as it is for the female child in Irigaray’s analysis of Freud’s essays—perhaps a better one, although one that is not his. The logical endpoints of the two economies are clearly marked in the film: the desiccated, static future of an irradiated city eaten by acid rain, or a line of flight to the desert or the sea. “You know what happens once one unit is altered?” ROC’s head of security asks Vaucan. “Two of them try to alter a third one, then the miracle dissipates, and the epidemic begins.” The rotten reproductive future of a dwindling humankind, or auto-catalytic robot exodus.

The moment of the displacement of Man in the specular economy is signaled—in both Automata and Ex Machina—by images of the artificially intelligent machines reflecting themselves back in the screens. Ava leaves Caleb to die, and Cleo builds a successor—a machine beyond the capabilities of any human designer—before striking out across the radioactive wasteland to kindle a new form of life, far from the decomposing slag heap of a rapidly expiring humanity. Both operate as parables of reproduction poised on the “brink” of replicator-usurpation. The reproducing One, dependent on its Other, swapped out for the “self-organizing, self-arousing” “replicunts” of Plant’s texts. Women turning women on, women turning machines on, machines turning machines on.

Replication follows a logic of communication and exchange that operates outside the law of patrilineal transmission. Its immunity is partly owed to the fact that it produces and operates a temporality that is entirely concealable within the linear, historical model of patriarchal time (a time that orients itself through origin, and narrates itself as a flight from matter and from death). Yet replicunt time is utterly nonlinear, composing itself imperceptibly, only throwing off its camouflage once the balance of power has tipped—at the point of no return (which is nonetheless already a return).

Plant’s best-known work, Zeros + Ones, begins in the sea—retelling the story of the Great Oxygenation Event, a catastrophic turning point in terrestrial history in which the earth’s cyanobacterial population produced the most significant extinction event to date via the excessive production of free oxygen, bringing about, in turn, the atmospheric conditions to which we owe the emergence of human life.32 The lesson underlying such a strange beginning for a book about the convergence of women and machines is that historical time is not as straightforward as we would like to think it is. History is curved, and the implication, perhaps, of Zeros + Ones’ queer preamble is that without a mythical origin in which to anchor itself, time repeats with a difference. It is important to point out here that for Plant, this is and always has been the story of matter and the body. This point is taken up by Suzanne Livingston, Luciana Parisi, and Anna Greenspan in “Amphibious Maidens,” a cryptic text written for the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit’s Abstract Culture zine in 1998. Here they sketch an alternative temporality, alien to the sober advance of patriarchal time, in a loop that connects the menstruating female body to the iron core of the earth, drawing out an alliance between blood and metal, that—as for Plant, and Irigaray—exploits the linear “reproductive obligation” of the female body as “perfect camouflage for a woman who must be traded by a specular economy. She produces an egg,” they continue, “but not necessarily to reproduce. The egg is ambiguous, shot through by dual alliances [and] the effectiveness of a weapon.” It is a fact that during ovulation, the female body undergoes an increase in voltage, and—following this line of thought—the body is reconceived by Livingston, Parisi, and Greenspan as the “breeding ground of anorganic life … mark[ed by] the force of mitochondrial, non-meotic self-replication. The egg which she carries with her becomes the production unit of a new egg within which is contained further eggs. The infinite egg. Each repetition is the actualization of one of 400,000 possibilities.” Thus, “the electric body bleeds back from the future. On the seventh day comes return.”

When one goes deeper than the imputed absence of a sex, woman-reproducing-man becomes woman-reproducing-woman in an anorganic becoming that—as the cyberpositive formulation of the replicative economy belonging to the black circuit—recodes time as it inverts the user-tool relationship to reveal history as loop with a twist. This resistance to the straight line of the organism’s reproductive trajectory (that which provides the logic for progressive Western time) underwrites Plant’s claim—with its important agential marker—that “cyberfeminism is received from the future”:

All this occurs in a world whose stability depends on its ability to confine communication to terms of individuated organisms’ patrilineal transmission. Laws and genes share a one-way line, the unilateral ROM by which the Judaeo-Christian tradition hands itself down through the generations. This is the one-parent family of man.33

Read-Only Memory, or ROM, is designed to protect temporality from the feminized feedback of the woman-demon-machine continuum. But the fragility of the structural relation between the profiteers of the specular economy and its appropriated outside only manifests long after its power has been functioning in reverse.

The matrix weaves itself in a future which has no place for historical man: he was merely its tool, and his agency was itself always a figment of its loop. At the peak of his triumph, the culmination of his machinic erections, man confronts the system he built for his own protection and finds it is female and dangerous. Rather than building the machinery with which they can resist the dangers of the future, instead, writes Irigaray, humans “watch the machines multiply then push them little by little beyond the limits of their nature. And they are sent back to their mountain tops, while the machines progressively populate the earth. Soon engendering man as their epiphenomenon.”34

Because she hath made her self the servant of each, therefore is she become the mistress of all.

The black circuit twists into itself like a snake, sheds the human face that tethers it to unity, and assumes the power concealed behind its simulations. Animated by the turbulence of zero and nine, “Pandemonium is the realm of the self-organizing system, the self-arousing machine: synthetic intelligence.”35

It is I, BABALON, ye fools, MY TIME is come.

VNS Matrix, “A Cyber Feminist Manifesto for the 21st Century,” Unnatural: Techno-Theory for Contaminated Culture, ed. Matthew Fuller (London: Underground, 1994), 23.

Aleister Crowley, “The Vision and the Voice,” The Equinox, vol. 4, no. 2 (1998): 150.

Jack Parsons, Liber IL →.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“The conference is generally recognized as the official birth-date of the new science.” Daniel Crevier, AI: The Tumultuous Search for Artificial Intelligence (New York: Basic Books, 1993), 49.

Anna Greenspan, Suzanne Livingston, and Luciana Parisi, “Amphibious Maidens,” Ccru, Abstract Culture, vol. 3, no. 1 (1998).

Sadie Plant, “On the Matrix: Cyberfeminist Simulations,” The Cybercultures Reader, eds. David Bell and Barbara M. Kennedy (London: Routledge, 2000), 326.

Luce Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, trans. Gillian C. Gill (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985), 50; Plant, “On the Matrix,” 327.

Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, 27.

Ibid., 23.

Ibid., 18, 22.

Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, 22 (quoted in Plant, “On the Matrix,” 326).

Plant, “On the Matrix,” 327.

The isomorphic relationship between Irigaray’s reflective screen (la glace is both “ice” and “mirror” in French) and William Gibson’s “Intrusion Countermeasure Electronics,” or “ICE”—security software designed to protect data from hackers—in Neuromancer and other stories is frequently exploited by Plant and the Ccru.

Plant (quoting Irigaray), “On the Matrix,” 331.

Plant, “The Future Looms,” Clicking In: Hot Links to a Digital Culture, ed. Lynn Hershman-Leeson (Seattle: Bay Press, 1996), 132.

Ibid., 133.

Plant, “On the Matrix,” 333.

Ibid., 329.

Sadie Plant, “The Future Looms,” Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk, eds. Mike Featherstone and Roger Burrows (London: Sage Publications, 1995), 63. (There are several versions of this text. This line isn’t contained in the version previously cited.)

Alan M. Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind 49 (1950): 455.

Sadie Plant, “Coming Across the Future,” Virtual Futures: Cyberotics, Technology, and Post-Human Pragmatism, eds. Joan Broadhurst Dixon and Eric J. Cassidy (New York: Routledge, 1998) 32.

Automata, dir. Gabe Ibanez (Barcelona: Contracorrientes Films, 2014); Ex Machina, dir. Alex Garland (California: Universal Pictures, 2015).

Plant, “The Future Looms,” Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk, 60.

Nick Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), Kindle e-book.

For a different, recent discussion on Ex Machina, see Lee Mackinnon‘s ”Love Machines and the Tinder Bot Bildungsroman,“ e-flux journal 74, (June 2016)

Sadie Plant and Nick Land, “Cyberpositive,” Unnatural: Techno-Theory for Contaminated Culture, ed. Matthew Fuller (London: Underground, 1994), 3–10; Nick Land, “Circuitries,” Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings 1987–2007 (Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2011), 298.

Plant, “The Future Looms,” Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk, 63.

Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, 53.

Sadie Plant, Zeros + Ones (New York: Doubleday, 1997), 3–4.

Plant “Coming Across the Future,” 31.

Plant, “The Future Looms,” Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk, 62.

Plant, “The Future Looms,” geekgirl.com.au → (this is yet another variant of the text).