The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 produces a truth effect that marks a rupture. It is nevertheless an intrinsically equivocal text, as is indicated by the dualities of its title and of its first line: rights of man and of the citizen, are born and remain, free and equal. Each of these dualities, and particularly the first, which divides the origin, harbor the possibility of antithetical readings: Is the founding notion that of man, or of the citizen? Are the rights declared those of the citizen as man, or those of man as citizen? In the interpretation sketched out here, it is the second reading that must take precedence: The stated rights are those of the citizen, the objective is the constitution of citizenship—in a radically new sense. In fact neither the idea of humanity nor its equivalence with freedom are new. Nor, as we have seen, are they incompatible with a theory of originary subjection: the Christian is essentially free and subject, the subject of the Prince is “franc.” What is new is the sovereignty of the citizen, which entails a completely different conception (and a completely different practical determination) of freedom. But this sovereignty must be founded retroactively on a certain concept of man, or, better, in a new concept of man that contradicts what the term previously connoted.

Why is this foundation necessary? I do not believe it is, as is often said, because of a symmetry with the way the sovereignty of the Prince was founded in the idea of God, because the sovereignty of the people (or of the “nation”) would need a human foundation in the same way that imperial or monarchical sovereignty needed a divine foundation, or, to put it another way, by virtue of a necessity inherent in the idea of sovereignty, which leads to putting Man in the place of God.1 On the contrary, it is because of the dissymmetry that is introduced into the idea of sovereignty from the moment that it has devolved to the “citizens”: until then, the idea of sovereignty had always been inseparable from a hierarchy, from an eminence; from this point forward the paradox of sovereign equality, something radically new, must be thought. What must be explained (at the same time as it is declared) is how the concept of sovereignty and equality can be noncontradictory. The reference to man, or the inscription of equality in human nature as equality “of birth,” which is not at all evident and even improbable, is the means of explaining this paradox.2 This is what I will call a hyperbolic proposition.

It is also the sudden appearance of a new problem. One paradox (the equality of birth) explains another (sovereignty as equality). The political tradition of antiquity, to which the revolutionaries never cease to refer (Rome and Sparta rather than Athens), thought civic equality to be founded on freedom and exercised in the determinate conditions of this freedom (which is a hereditary or quasi-hereditary status). It is now a matter of thinking the inverse: a freedom founded on equality, engendered by the movement of equality. Thus an unlimited or, more precisely, self-limited freedom: having no limits other than those it assigns to itself in order to respect the rule of equality, that is, to remain in conformity with its principle. In other terms, it is a matter of answering the question: Who is the citizen? and not the question: Who is a citizen? (or: Who are citizens?). The answer is: the citizen is a man in enjoyment of all his “natural” rights, completely realizing his individual humanity, a free man simply because he is equal to every other man. This answer (or this new question in the form of an answer) will also be stated, after the fact: the citizen is the subject, the citizen is always a supposed subject (legal subject, psychological subject, transcendental subject).

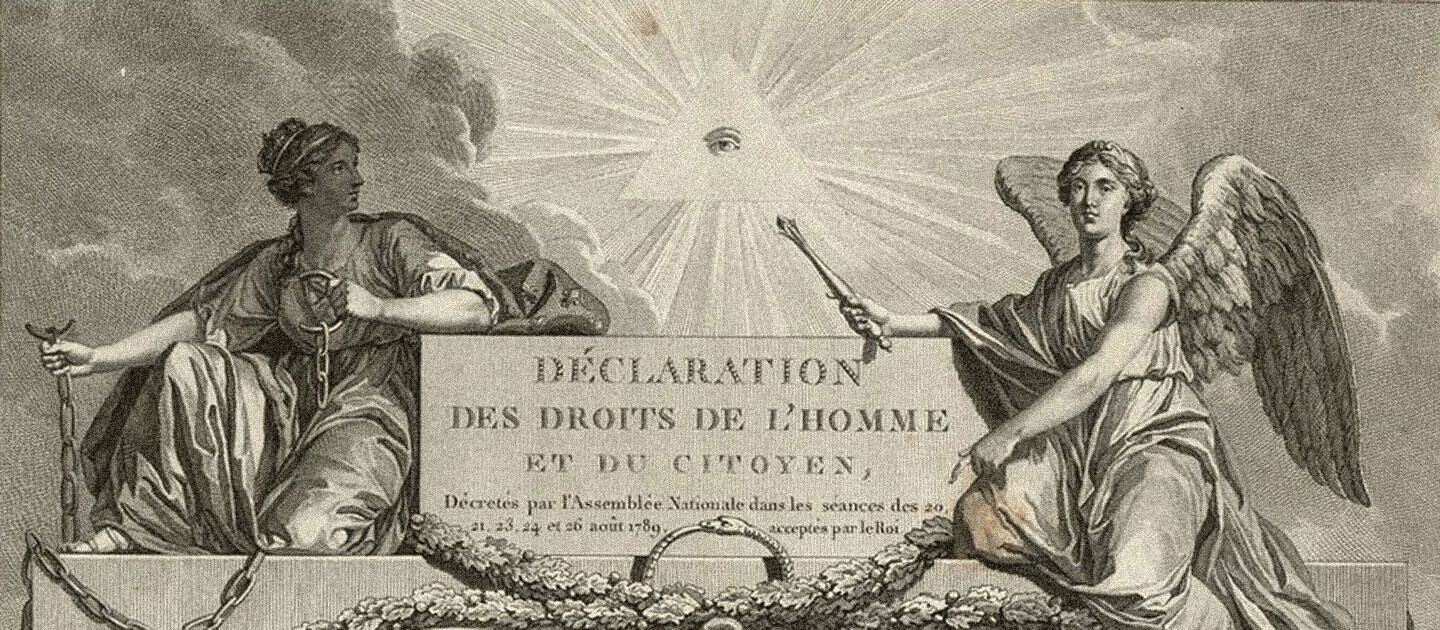

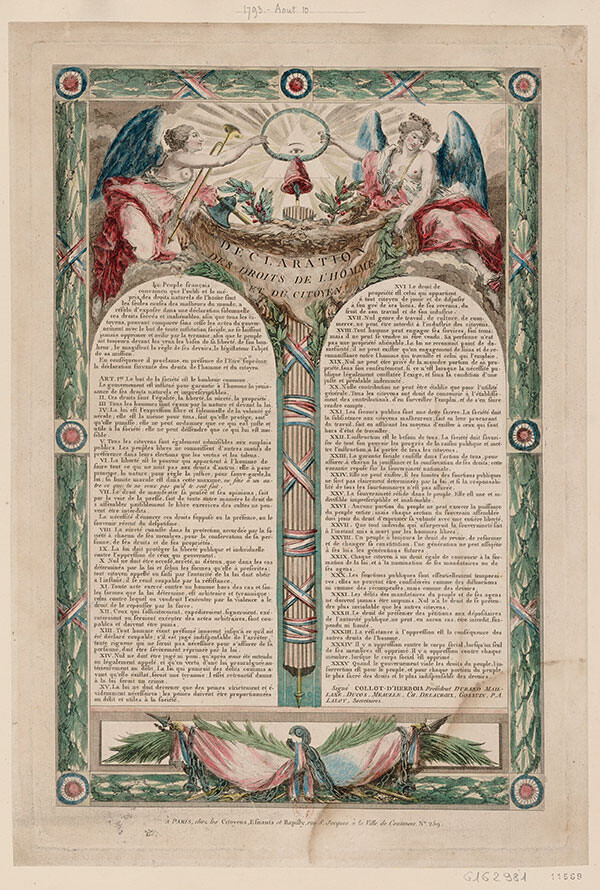

An illustrated header adorns a plate of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1793). Photo: Wikimedia commons.

I will call this new development the citizen’s becoming a subject (devenir sujet): a development that is doubtless prepared by a whole labor of definition of the juridical, moral, and intellectual individual; that goes back to the “nominalism” of the late Middle Ages, is invested in institutional and cultural practices, and reflected by philosophy, but that can find its name and its cultural position only after the emergence of the revolutionary citizen, for it rests upon the reversal of what was previously the subjectus. In the Declaration of Rights, and in all the discourses and practices that reiterate its effect, we must read both the presentation of the citizen and the marks of his becoming-a-subject. This is all the more difficult in that it is practically impossible for the citizen(s) to be presented without being determined as subject(s). But it was only by way of the citizen that universality could come to the subject. An eighteenth-century dictionary had stated: “In France, other than the king, all are citizens.”3 The revolution will say: if anyone is not a citizen, then no one is a citizen. “All distinction ceases. All are citizens, or must be, and whoever is not must be excluded.”4

The idea of the rights of the citizen, at the very moment of his emergence, thus institutes an historical figure that is no longer the subjectus, and not yet the subjectum. But from the beginning, in the way it is formulated and put into practice, this figure exceeds its own institution. This is what I called, a moment ago, the statement of a hyperbolic proposition. Its developments can only consist of conflicts, whose stakes can be sketched out.

First of all, there exist conflicts with respect to the founding idea of equality. The absolutism of this idea emerges from the struggle against “privilege,” when it appeared that the privileged person was not he who had more rights but he who had less: each privilege, for him, is substituted for a possible right, even though at the same time his privilege denies rights to the nonprivileged. In other words, it appeared that the “play” (jeu) of right—to speak a currently fashionable language—is not a “zero-sum” game: that is what distinguishes it from the play of power, the “balance of power.” Rousseau admirably developed this difference on which the entire argumentation of the Social Contract is based: a supplement of rights for one is the annihilation of the rights of all; the effectivity of right has as its condition that each has exactly “as much,” neither more nor fewer right(s), than the rest.

Two paths are open from this point. Either equality is “symbolic,” which means that each individual, whatever his strengths, his power, and his property, is reputed to be equivalent to every individual in his capacity as citizen (and in the public acts in which citizenship is exercised). Or equality is “real,” which means that citizenship will not exist unless the conditions of all individuals are equal, or at least equivalent: then, in fact, power’s games will no longer be able to pose an obstacle to the play of right; the power proper to equality will not be destroyed by the effects of power. Whereas symbolic equality is all the better affirmed, its ideality all the better preserved and recognized as unconditional when conditions are unequal, real equality supposes a classless society, and thus works to produce it. If a proof is wanted of the fact that the antinomy “formal” and “real” democracy is thus inscribed from the very beginning in the text of 1789 it will suffice to reread Robespierre’s discourse on the “marc d’argent” (April 1791).5

But this antinomy is untenable, for it has the form of an all-or-nothing (it reproduces within the field of citizenship the all-or-nothing of the subject and the citizen). Symbolic equality must be nothing real, but a universally applicable form. Real equality must be all or, if one prefers, every practice, every condition must be measured by it, for an exception destroys it. It can be asked—we will return to this point—whether the two mutually exclusive sides of this alternative are not equally incompatible with the constitution of a “society.” In other terms, civic equality is indissociable from universality but separates it from community. The restitution of the latter requires either a supplement of symbolic form (to think universality as ideal Humanity, the reign of practical ends) or a supplement of substantial egalitarianism (communism, Babeuf’s “order of equality”). But this supplement, whatever it may be, already belongs to the citizen’s becoming a subject.

Second, there exist conflicts with respect to the citizen’s activity. What radically distinguishes him from the subject of the Prince is his participation in the formation and application of the decision: the fact that he is legislator and magistrate. Here, too, Rousseau, with his concept of the “general will,” irreversibly states what constitutes the rupture. The comparison with the way in which medieval politics had defined the “citizenship” of the subject, as the right of all to be well governed, is instructive.6 From this point forward the idea of a “passive citizen” is a contradiction in terms. Nevertheless, as is well known, this idea was immediately formulated. But let us look at the details.

Does the activity of the citizen exclude the idea of representation? This position has been argued: whence the long series of discourses identifying active citizenship and “direct democracy,” with or without reference to antiquity.7 In reality this identification rests on a confusion.

Initially, representation is a representation before the Prince, before Power, and, in general, before the instance of decision-making, whatever it may be (incarnated in a living or anonymous person, itself represented by officers of the State). This is the function of the Old Regime’s “deputies of the Estates,” who present grievances, supplications, and remonstrances (in many respects this function of representing those who are administered to the administration has in fact again become the function of the numerous elected assemblies of the contemporary State).

The representation of the sovereign in its deputies, inasmuch as the sovereign is the people, is something entirely different. Not only is it active, it is the act of sovereignty par excellence: the choice of those who govern, the corollary of which is monitoring them. To elect representatives is to act and to make possible all political action, which draws its legitimacy from this election. Election has an “alchemy,” whose other aspects we will see further on: as the primordial civic action, it singularizes each citizen, responsible for his vote (his choice), at the same time as it unifies the “moral” body of the citizens.8 We will have to ask again, and in greater depth, to what extent this determination engages the dialectic of the citizen’s becoming-a-subject: Which citizens are “representable,” and under which conditions? Above all: Who should the citizens be in order to be able to represent themselves and to be represented? (For example: Does it matter that they be able to read and write? Is this condition sufficient? etc.). In any case we have here, again, a very different concept from the one antiquity held of citizenship, which, while it too implied an idea of activity, did not imply one of sovereign will. Thus the Greeks privileged the drawing of lots in the designation of magistrates as the only truly democratic method, whereas election appeared to them to be “aristocratic” by definition (Aristotle).

It is nonetheless true that the notion of a representative activity is problematic. This can be clearly seen in the debate over the question of the binding mandate: Is it necessary, in order for the activity of the citizens to manifest itself, that their deputies be permanently bound by their will (supposing it to be known), or is it sufficient that they be liable to recall, leaving them the responsibility to interpret the general will by their own activity? The dilemma could also be expressed by saying that citizenship implies a power to delegate its powers, but excludes the existence of “politicians,” of “professionals,” a fortiori of “technicians” of politics. In truth this dilemma was already present in the astonishing Hobbesian construction of representation, as the doubling of an author and an actor, which remains the basis of the modern State.

But the most profound antinomy of the citizen’s activity concerns the law. Here again Rousseau circumscribes the problem by posing his famous definition: “As for the associates, collectively they take the name people, and individually they are called Citizens as participating in the sovereign authority and Subjects as submitted to the laws of the State.”9

It can be seen by this formulation … that each individual, contracting, so to speak, with himself, finds himself engaged in a double relationship … Consequently it is against the nature of the political body for the Sovereign to impose upon itself a law that it cannot break … by which it can be seen that there is not nor can there be any sort of fundamental law which obliges the body of the people, not even the social contract … Now the Sovereign, being formed only of the individuals who compose it, does not and cannot have an interest opposed to theirs; consequently the Sovereign power has no need of a guarantee toward the subjects, for it is impossible that the body wish to harm all its members … But this is not he case for the subjects toward the sovereign, where despite the common interest, nothing would answer for their engagements if means to insure their fidelity were not found. In fact each individual can, as man, have a particular will contrary or dissimilar to the general will that he has as citizen … He would enjoy the rights of a citizen without being willing to fulfill the duties of a subject; an injustice whose progress would cause the ruin of the political body. In order for the social pact not to become a vain formula, it tacitly includes the engagement … that whoever refuses to obey the general will will be compelled to do so by any means available: which signifies nothing else than that he will be forced to be free.10

It was necessary to cite this whole passage in order that no one be mistaken: in these implacable formulas, we see the final appearance of the “subject” in the old sense, that of obedience, but metamorphosed into the subject of the law, the strict correlative of the citizen who makes the law.11 We also see the appearance, under the name of “man,” split between his general interest and his particular interest, of he who will be the new “subject,” the Citizen Subject.

It is indeed a question of an antinomy. Precisely in his capacity as “citizen,” the citizen is (indivisibly) above any law, otherwise he could not legislate, much less constitute: “There is not, nor can there be, any sort of fundamental law that obliges the body of the people, not even the social contract.” In his capacity as “subject” (that is, inasmuch as the laws he formulates are imperative, to be executed universally and unconditionally, inasmuch as the pact is not a “vain formula”) he is necessarily under the law. Rousseau (and the Jacobin tradition) resolve this antinomy by identifying, in terms of their close “relationship” (that is, in terms of a particular point of view), the two propositions: just as one citizen has neither more nor less right(s) than another, so he is neither only above, nor only under the law, but at exactly the same level as it. Nevertheless he is not the law (the nomos empsychos). This is not the consequence of a transcendence on the part of the law (of the fact that it would come from Elsewhere, from an Other mouth speaking atop some Mount Sinai), but a consequence of its immanence. Or yet another way: there must be an exact correspondence between the absolute activity of the citizen (legislation) and his absolute passivity (obedience to the law, with which one does not “bargain,” which one does not “trick”). But it is essential that this activity and this passivity be exactly correlative, that they have exactly the same limits. The possibility of a metaphysics of the subject already resides in the enigma of this unity of opposites (in Kant, for example, this metaphysics of the subject will proceed from the double determination of the concept of right as freedom and as compulsion). But the necessity of an anthropology of the subject (psychological, sociological, juridical, economic …) will be manifest from the moment that, in however small a degree, the exact correlation becomes upset in practice: when a distinction between active citizens and passive citizens emerges (a distinction with which we are still living), and with it a problem of the criteria of their distinction and of the justification of this paradox. Now this distinction is practically contemporary with the Declaration of Rights itself; it is in any case inscribed in the first of the Constitutions “based” on the Declaration of Rights. Or, quite simply, when it becomes apparent that to govern is not the same as to legislate or even to execute the laws, that is, that political sovereignty is not the mastery of the art of politics.

Finally, there exist conflicts with respect to the individual and the collective. We noted above that the institution of a society or a community on the basis of principles of equality is problematic. This is not—or at least not uniquely—due to the fact that this principle would be identical to that of the competition between individuals (“egotism,” or a freedom limited only by the antagonism of interests). It is even less due to the fact that equality would be another name for similarity, that it would imply that individuals are indiscernible from one another and thus incompatible with one another, preyed on by mimetic rivalry. On the contrary, equality, precisely inasmuch as it is not the identification of individuals, is one of the great cultural means of legitimating differences and controlling the imaginary ambivalence of the “double.” The difficulty is rather due to equality itself: In this principle (in the proposition that men, as citizens, are equal), even though there is necessarily a reference to the fact of society (under the name of “polity”), there is conceptually too much (or not enough) to “bind” a society. It can be see clearly here how the difficulty arises from the fact that, in the modern concept of citizenship, freedom is founded in equality and not vise versa (the “solution” of the difficulty will in part consist precisely of reversing this primacy, to make freedom into a foundation, even, metaphysically, to identify the originary with freedom).

Equality in fact cannot be limited. Once some x’s (“men”) are not equal, the predicate of equality can no longer be applied to anyone, for all those to whom it is supposed to be applicable are in fact “superior,” “dominant,” “privileged,” etc. Enjoyment of the equality of rights cannot spread step by step, beginning with two individuals and gradually extending to all: it must immediately concern the universality of individuals, let us say, tautologically, the universality of x’s that it concerns. This explains the insistence of the cosmopolitan theme in egalitarian political thought, or the reciprocal implication of these two themes. It also explains the antinomy of equality and society for, even when it is not defined in “cultural,” “national,” or “historical” terms, a society is necessarily a society, defined by some particularity, by some exclusion, if only by a name. In order to speak of “all citizens,” it is necessary that somebody not be a citizen of said polity.

Likewise, equality, even though it preserves differences (it does not imply that Catholics are Protestants, that blacks are whites, that women are men, or vice versa: it could even be held that without differences equality would be literally unthinkable), cannot itself be differentiated: differences are close by it but do not come from its application. We have already glimpsed this problem with respect to activity and passivity. It takes on its full extension once it is a question of organizing a society, that is of instituting functions and roles in it. Something like a “bad infinity” is implied here by the negation of the inequalities which are always still present in the principle of equality, and which form, precisely, its practical effectiveness. This is, moreover, exactly what Hegel will say.

The affirmation of this principle can be seen in 1789 in the statement that the king himself is only a citizen (“Citizen Capet”), a deputy of the sovereign people. Its development can be seen in the affirmation that the exercise of a magistrature excludes one from citizenship: “The soldier is a citizen; the officer is not and cannot be one.”12 “Ordinarily, people say: the citizen is someone who participates in honors and dignities; they are mistaken. Here he is, the citizen: he is someone who possesses no more goods than the law allows, who exercises no magistrature and is independent of the responsibility of those who govern. Whoever is a magistrate is no longer part of the people. No individual power can enter the people … When speaking to a functionary, one should not say citizen; this title is above him.”13 On the contrary, it may be thought that the existence if a society always presupposes an organization, and that the latter in turn always presupposes an element of qualification or differentiation from equality and thus of “nonequality” developed on the basis of equality itself (which is not on that account a principle of inequality).14 If we call this element “archy,” we will understand that one of the logics of citizenship leads to the idea of anarchy. It was Sade who wrote, “Insurrection should be the permanent state of the republic,” and the comparison with Saint Just has been made by Maurice Blanchot.15

It will be said that the solution to this aporia is the idea of a contract. The contractual bond is in fact the only one that thinks itself as absolutely homogeneous with the reciprocal action of equal individuals,16 presupposing only this equality. No other presuppositions? All the theoreticians are in agreement that some desire for sociability, some interest in bringing together the forces and in limiting freedoms by one another, or some moral ideal, indispensable “motor forces,” would also be required. It will in fact be agreed that the proper form of the contract is that of a contract of association, and that the contract of subjection is an ideological artifact destined to divert the benefits of the contractual form to the profit of an established power. But it remains a question whether the social contract can be thought as a mechanism that “socializes” equals purely by virtue of their equality. I think that the opposite is the case: that the social contract adds to equality a determination that compensates for its “excess” of universality. To this end equality itself must be thought as something other than a naked principle; it must be justified, or one must confer on it that which Derrida not long ago called an originary supplement.

This is why all the theories of the contract include a “deduction” of equality as an indispensable preliminary, showing how it is produced or how it is destroyed and restored in a dialectic either of natural sociability and unsociability or of the animality and humanity in man (the extreme form being that of Hobbes: equality is produced by the threat of death, in which freedom is promptly annihilated). The Declaration of 1789 gives this supplement its most economical form, that of a de jure fact: “Men are born and remain …”

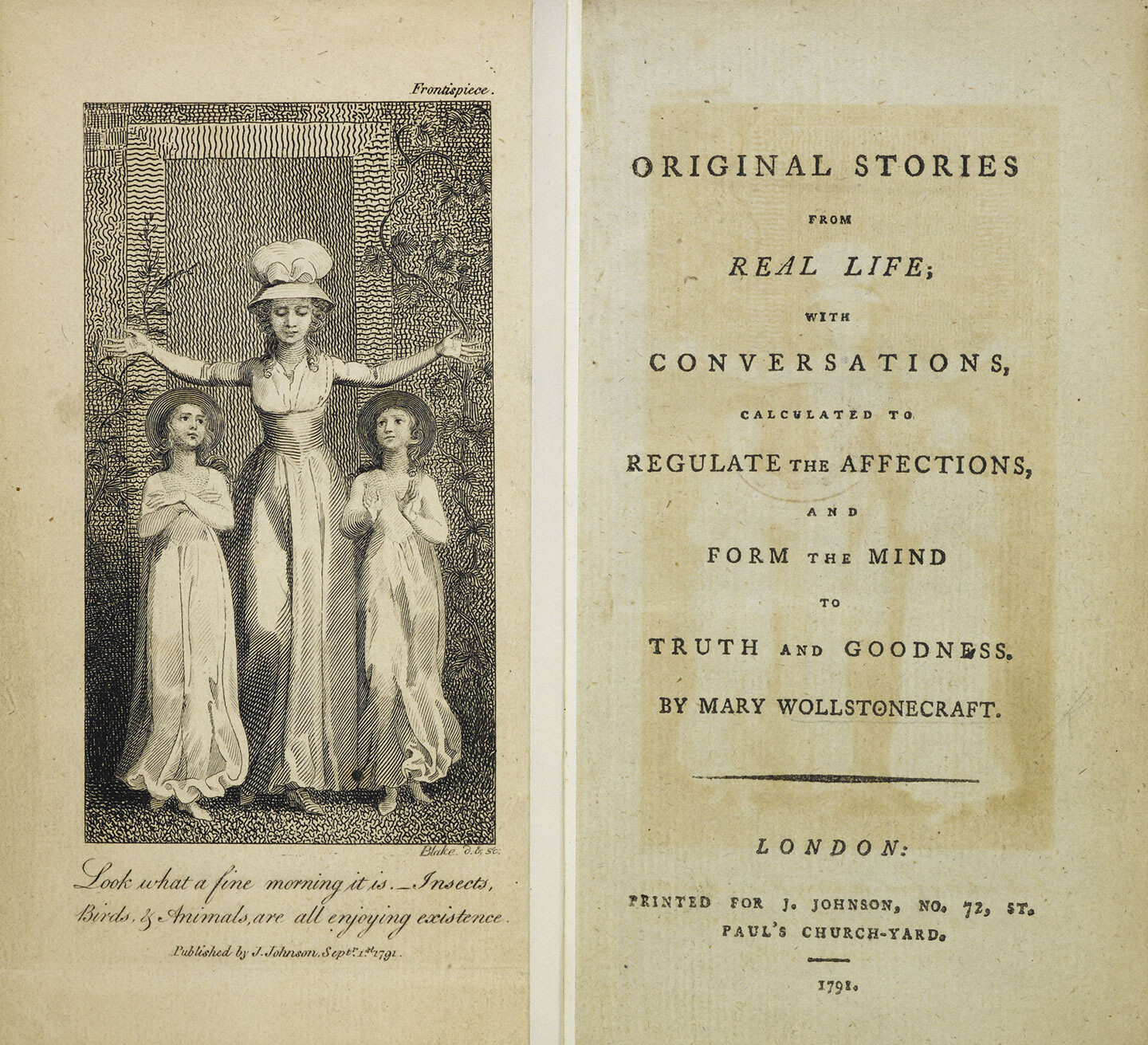

William Blakes illustration for the frontispiece of Mary Wollstonecraft’s book Original Stories from Real Life (1791).

From One Subjection to the Other

I think that, under these conditions, the indetermination of the figure of the citizen—referred to equality—can be understood with respect to the major alternatives of modern political and sociological thought: individual and collectivity, public sphere and private sphere. The citizen properly speaking is neither the individual nor the collective, just as he is neither an exclusively public being nor a private being. Nevertheless, these distinctions are present in the concept of the citizen. It would not be correct to say that they are ignored or denied: it should rather be said that they are suspended, that is, irreducible to fixed institutional boundaries which would pose the citizen on one side and a noncitizen on the other.

The citizen is unthinkable as an “isolated” individual, for it is his active participation in politics that makes him exist. But he cannot on that account be merged into a “total” collectivity. Whatever may be said about it, Rousseau’s reference to a “moral and collective body composed of as many members as there are votes in the assembly,”17 produced by the act of association that “makes a people a people,”18 is not the revival but the antithesis of the organicist idea of the corpus mysticum (the theologians have never been fooled on this point).19 The “double relationship” under which the individuals contract also has the effect of forbidding the fusion of individuals in a whole, whether immediately or by the mediation of some “corporation.” Likewise, the citizen can only be thought if there exists, at least tendentially, a distinction between public and private: he is defined as a public actor (and even as the only possible public actor). Nevertheless he cannot be confined to the public sphere, with a private sphere—whether the latter is like the oikos of antiquity, the modern family (the one that will emerge from the civil code and that which we now habitually call “the invention of private life”), or a sphere of industrial and commercial relations that are nonpolitical20 belongs to [the capitalist] just as much as the wine that is the product of the process of fermentation taking place in his cellar.”]—being held in reserve. If only for the reason that, in such a sphere, to become other than himself the citizen would have to enter into relationships with noncitizens (or with individuals considered as noncitizens: women, children, servants, employees). The citizen’s “madness,” as is known, is not the abolition of private life but its transparency, just as it is not the abolition of politics but its moralization.

To express this suspension of the citizen we are obliged to search in history and literature for categories that are unstable and express instability. The concept of mass, at a certain moment of its elaboration, would be an example, as when Spinoza speaks of both the dissolution of the (monarchical) State and its (democratic) constitution as a “return to the mass.”21 This concept is not unrelated, it would seem, to that which in the Terror will durably inspire the thinkers of liberalism with terror.

I have presented the Declaration of Rights as a hyperbolic proposition. It is now possible to reformulate this idea: in effect, in this proposition, the wording of the statement always exceeds the act of its enunciation [l’enoncé exceed toujours l’énonciation], the import of the statement already goes beyond it (without our knowing where), as was immediately seen in the effect of inciting the liberation that it produced. In the statement of the Declaration, even though this is not at all the content of the enunciation of the subsequent rights, we can already hear the motto that, in another place and time, will become a call to action: “It is right to revolt.” Let us note once more that it is equality that is at the origin of the movement of liberation.

All sorts of historical modalities are engaged here. Thus the Declaration of 1789 posits that property—immediately after freedom—is a “natural and imprescriptable right of man” (without, however, going so far as to take up the idea that property is a condition of freedom). And as early as 1791 the battle is engaged between those who conclude that property qualifies the constitutive equality of citizenship (in other words that “active citizens” are proprietors), and those who posit that the universality of citizenship must take precedence over the right of property, even should this result in a negation of the unconditional character of the latter. As Engels noted, the demand for the abolition of class differences is expressed in terms of civic equality, which does not signify that the latter is only a period costume, but on the contrary that it is an effective condition of the struggle against exploitation.

Likewise, the Constitutions that are “based” on the principles of 1789 immediately qualify—explicitly and implicity—the citizen as a man (= a male), if not as a head of household (this will come with the Napoleonic Code). Nevertheless, as early as 1791 an Olympe de Gouges can be found drawing from these same principles the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and Citizenness (and, the following year, with Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman), and the battle—one with a great future, though not much pleasure—over the question of whether the citizen has a sex (thus, what the sex of man as citizen is) is engaged.

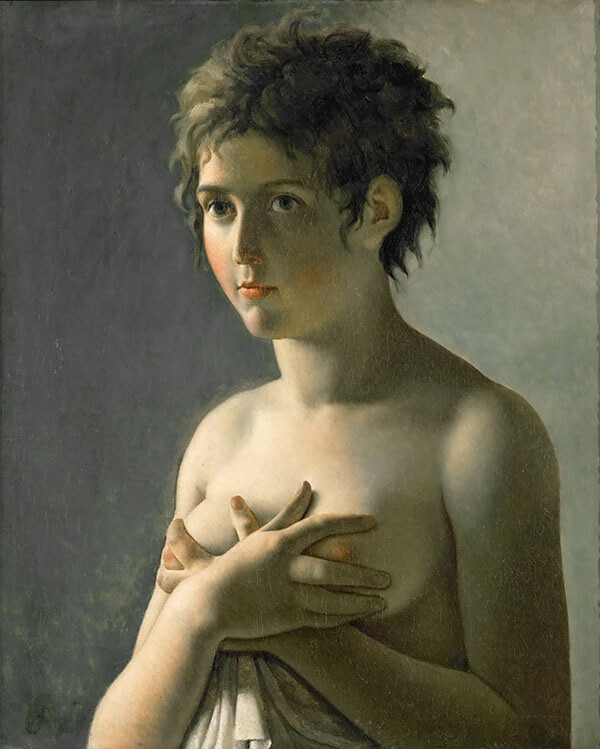

Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, Girl with Coiffure à la Titus, 1794. Oil on canvas. The short cut that was meant to imitate the haircut given to those about to be executed during the Terror in France.

Finally, the Declaration of 1789 does not speak of the color of citizens, and—even if one refuses to consider22 this silence to be a necessary condition for the representation of the political relations of the Old Regime (subjection to the Prince and to the seigneurs) as “slavery,” even as true slavery (that of the blacks) is preserved—it must be admitted that it corresponds to powerful interests among those who collectively declare themselves “sovereign.” It is nonetheless the case that the insurrection for the immediate abolition of slavery (Toussaint L’Ouverture) takes place in the name of an equality of rights that, as stated, is indiscernible from that of the “sans culottes” and other “patriots,” though the slaves, it is true, did not wait for the fall of the Bastille to revolt.23

Thus that which appeared to us as the indetermination of the citizen (in certain respects compatible to the fugitive moment that was glimpsed by Aristotle under the name of archè aoristos, but that now would be developed as a complete historical figure) also manifests itself as the opening of a possibility: the possibility for any given realization of the citizen to be placed in question and destroyed by a struggle for equality and thus for civil rights. But this possibility is not in the least a promise, much less an inevitability. Its concretization and explicitation depend entirely on an encounter between a statement and situations or movements that, from the point of view of the concept, are contingent.24 If the citizen’s becoming-a-subject takes the form of a dialectic, it is precisely because both the necessity of “founding” institutional definitions of the citizen and the impossibility of ignoring their contestation—the infinite contradiction within which they are caught—are crystallized in it.

There exists another way to account for the passage from the citizen to the subject (subjectum), coming after the passage from citizen to the subject (subjectus) to the citizen, or rather immediately overdetermining it. The citizen as defined by equality, absolutely active and absolutely passive (or, if one prefers, capable of autoaffection: that which Fichte will call das Ich), suspended between individuality and collectivity, between public and private: Is he the constitutive element of a State? Without a doubt, the answer is yes, but precisely insofar as the State is not, or not yet, a society. He is, as Pierre-François Moreau has convincingly argued, a utopic figure, which is not to say an unreal or millenarist figure projected into the future, but the elementary term of an “abstract State.”25 Historically, this abstract State possesses an entirely tangible reality: that of the progressive deployment of a political and administrative right in which individuals are treated by the state equally, according to the logic of situations and actions and not according to their condition or personality. It is this juridico-administrative “epochè” of “cultural” or “historical” differences, seeking to create its own conditions of possibility, that paradoxically becomes explicit to itself in the minutely detailed egalitarianism of the ideal cities of the classical Utopia, with their themes of closure, foreignness, and rational administration, with their negation of property. When it becomes clear that the condition of conditions for individuals to be treated equally by the State (which is the logic of its proper functioning: the suppression of the exception) is that they also be equally entitled to sovereignty (that is, it cannot be done for less, while conserving subjection), then the “legal subject” implicit in the machinery of the “individualist” State will be made concrete in the excessive person of the citizen.

But this also means—taking into account all that precedes—that the citizen can be simultaneously considered as the constitutive element of the State and as the actor of a revolution. Not only the actor of a founding revolution, a tabula rasa whence a State emerges, but the actor of a permanent revolution: precisely the revolution in which the principle of equality, once it has been made the basis or pretext of the institution of an inequality or a political “excess of power,” contradicts every difference. Excess against excess, then. The actor of such a revolution is no less “utopic” than the member of the abstract State, the State of the rule of law. It would be quite instructive to conduct the same structural analysis of revolutionary utopias that Moreau made of administrative utopias. It would doubtless show not only that the themes are the same, but also that the fundamental prerequisites of the individual defined by his juridical activity is identical with that of the individual defined by his revolutionary activity: he is the man “without property” (der Eigentumslos), “without particularities” (ohne Eigenschaften). Rather than speak of administrative utopias and revolutionary utopias, we should really speak of antithetical readings of the same utopia narratives and of the reversibility of these narratives.

In the conclusion of his book, Moreau describes Kant’s Metaphysics of Morals and his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View as the two sides of a single construction of the legal subject: on the one side, the formal deduction of his egalitarian essence; on the other, the historical description of all the “natural” characteristics (all the individual or collective “properties”) that form either the condition or the obstacle to individuals identifying themselves in practice as being subjects of this type (for example, sensibility, imagination, taste, good mental health, ethnic “character,” moral virtue, or that natural superiority that predisposes men to civil independence and active citizenship and women to dependence and political passivity). Such a duality corresponds fairly well to what Foucault, in The Order of Things, called the “empirico-transcendental doublet.” Nevertheless, to understand that this subject (which the citizen will be supposed to be) contains the paradoxical unity of a universal sovereignty and a radical finitude, we must envisage this constitution—in all the historical complexity of the practices and symbolic forms which it brings together—from both the point of view of the State apparatus and that of the permanent revolution. This ambivalence is his strength, his historical ascendancy. All of Foucault’s work, or at least that part of it which, by successive approximations, obstinately tries to describe the heterogeneous aspects of the great “transition” between the world of subjection and the world of right and discipline, “civil society,” and State apparatus, is a materialist phenomenology of the transmutation of subjection, of the birth of the Citizen Subject. As to whether this figure, like a face of sand at the edge of the sea, is about to be effaced with the next great sea change—that is another question. Perhaps it is nothing more than Foucault’s own utopia, a necessary support for the enterprise of stating that utopia’s facticity.

See the frequently developed theme, notably following Proudhon: Rousseau and the French revolutionaries substituted the people for the king of “divine right” without touching the idea of sovereignty, or “archy.”

In the Cahiers de doléance of 1789, one sees the peasants legitimize, by the fact that they are men, the claim to equality that they raise: to become citizens (notably by the suppression of the fiscal privileges and seigneurial rights). See Regine Robin, La société française en 1789: Semur-en-Auxois (Paris: Plon, 1970).

Pierre Richelet, Dictionnaire de la langue française, ancienne et moderne (Lyon, 1728), s.v. “citoyen.” Cited by Pierre Rétat, “Citoyen-Sujet, Civisme,” in Handbuch politisch-sozialer Grundbegriffe in Frankreich, 1680–1820, eds. Rolf Reichardt and Eberhard Schmitt (Munich: Oldenbourg, 1988), 9:79.

(Anon.), La liberté du peuple (Paris, 1789). Cited by Rétat, “Citoyen-Sujet, Civisme,” 91.

Maximilien Robespierre, Virtue and Terror, trans. John Howe, ed. and intro. Slavoj Žižek (New York: Verso, 2007), 5–19.

See Rene Fedou, L’État au Moyen Âge (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1971), 162–63.

See the discussion of apathy evoked by Moses I. Finley, Democracy, Ancient and Modern (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1985).

See Saint-Just, “Discours sur la Constitution de la France” (April 24, 1793): “The general will is indivisible … Representation and the law thus have a common principle.” Discours et rapports, ed. Albert Soboul (Paris: Éditions sociales, 1977), 107.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Du contrat social, 1, 6, in Oeuvres complètes, eds. Bernard Gagnebin and Marcel Raymond (Paris: Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1964), 3:362.

Ibid., I, 7, Oeuvres complètes, 3:362–64.

During the revolution, a militant grammarian will write: “France is no longer a kingdom, because it is no longer a country in which the king is everything and the people nothing … What is France? A new word is needed to express a new thing … We call a country sovereignly ruled by a king a kingdom (royaume); I will call a country in which the law alone commands a lawdom (loyaume).” Urbain Domergeue, Journal de la langue française, August 1, 1791. Cited by Sonia Branca-Rosoff, “Le loyaume des mots,” in Lexique 3 (1985): 47.

Louis-Sébastien Mercier and Jean-Louis Carra, Annales patriotiques, January 18, 1791. Cited by Rétat, “Citoyen-Sujet, Civisme,” 97.

Louis-Antoine Saint-Just, Fragments d’institutions républicaines, in Oeuvres complètes, ed. Michele Duval (Paris: Éditions Gérard Lebovici, 1984), 978. Cited by Rétat, “Citoyen-Sujet, Civisme,” 97.

The Declaration of Rights of 1789, First Article, immediately following “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights,” continues: “Social distinctions can only be founded on common utility.” Distinctions are social, and whoever says “society,” “social bond,” says “distinctions” (and not “inequalities,” which would contradict the principle). This is why freedom and equality must be predicated of man, and not of the citizen.

Maurice Blanchot, “Insurrection, the madness of writing,” in The Infinite Conversation, trans. Susan Hanson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 217–29.

Instead of reciprocal action, today one would say “communication” or “communicative action.”

Du contrat social, I, 6, Oeuvres complètes, 3:361.

Ibid., I, 5, 3:359.

I am entirely in agreement on this point with Robert Derathé’s commentary (against Vaughn) on the adjective “moral” in his notes to the Pléiade edition of Rousseau (Oeuvres complètes, 3:1446).

See Karl Marx, Capital, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 1:292. “The product [of the worker’s labor in his workshop

See Étienne Balibar, “Spinoza, l’anti-Orwell: La crainte des masses,” Les temps modernes 470 (September 1985): 353–94.

As Louis Sala-Molins does in Le Code Noir ou le calvaire de Canaan (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1987).

See Yves Benot, La révolution française et la fin des colonies (Paris: La Découverte, 1988).

Let us note that this thesis is not Kantian: the accent is placed on the citizen and not on the ends of man; the object of the struggle is not anticipated but discovered in the wake of political action; and each given figure is not an approximation of the regulatory ideal of the citizen but an obstacle to effective equality. Nor is this thesis Hegelian: Nothing obliges a new realization of the citizen to be superior to the preceding one.

Pierre-François Moreau, Le récit utopique: Droit naturel et roman de l’État (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1982).

Translated from the French by James Swenson. This text is the second half of the introductory essay for Étienne Balibar’s Citizen Subject, which was published last month in English by Fordham University Press. The first half appeared in e-flux journal 77 (November 2016).